essays

Native Voices Won’t Be Silenced

Talking with Elissa Washuta about trauma, authenticity & Native American Heritage Month

As a blogger for Ploughshares I cover indigenous and Asian lit from around the world. My coverage also, naturally, includes the US, Canada, and other Western nations. When blog readership stats came in recently I saw something that confirmed my suspicions of the reading and writing public who supposedly champion POC authors: There’s a lot of talk about reading POC, the C or color part of that acronym doesn’t extend beyond the Caucasian or African American mainstream.

Where is the indigenous element in POC?

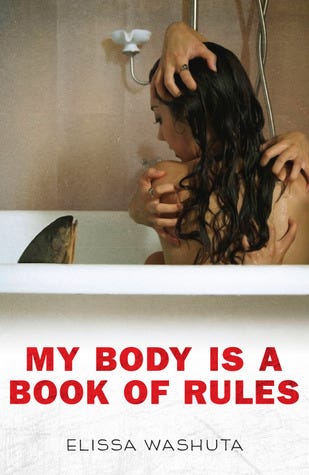

That’s where critically acclaimed Native nonfiction writer Elissa Washuta comes in. Author of personal essays and the memoir My Body Is a Book of Rules, she doesn’t dress up her writing with literary versions of moccasins and beaded buffalo hide dresses. Her skin might be a little too pale to suit the stereotype, as she’s said and written, yet she is an “unapologetic” member of the Cowlitz tribe.

Elissa holds an MFA from The University of Washington and currently serves as the undergraduate adviser for the Department of American Indian Studies at the University of Washington and a nonfiction faculty member in the MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts. She is a faculty advisor for Mud City Journal.

I interviewed her about November as Native American Heritage month, where to find work by indigenous writers, and being an edit-as-I-go writer.

Nichole L. Reber: Some of my friends from other countries have been asked by editors to mitigate the ethnic references in their work. My Guyanese friend, for instance, is a poet who’s been told he should eliminate his inherent Hindu references to be more accessible to readers. Have editors tried to censor you like this? Have you come across Native writers who self-censor?

Elissa Washuta: An editor has never told me to take out references to being Cowlitz/Cascade from my work. I don’t know that this means that I haven’t been censored. Like pretty much every other writer, I’ve been rejected many, many times, and I have wondered whether any of those rejections have to do with the fact that my work might be seen as “not Native enough” by readers who are looking for work with markers from a set created by Hollywood writers, fake shamans pulling a profit from paperbacks, and other non-Natives whose representations have come to be so strongly associated with us in too many people’s imaginations. Regarding other Natives who self-censor: it’s not something I think about, and certainly not something I’d call out a writer about. Each of us has an individual relationship with Indigeneity and it’s not up to me to evaluate whether it’s all there on the page. Not everything needs to be shared for readers’ consumption.

Reber: At the beginning of the month, Americans will vote for a President, then at the end of the month they’ll gorge on food and football in a supposed celebration of thanks for Natives’ helping out the first colonists. Few, however, recognize that it’s also Native American Heritage month. Does Native American Heritage month mean anything to you?

Washuta: I’ve become pretty jaded about Native American Heritage Month, because I sometimes see outlets only paying attention to Native voices and issues during November. That’s when the lists of notable Natives come out from publications who don’t publish work about Native writers the rest of the year (and still might not actually feature any Native bylines in November). Last November, the brick-and-mortar Amazon.com store in Seattle presented my book in a special “Native Voices” display in November. The book wasn’t in the store when I returned during the first week of December. All that said, I do look forward to the flurry of activity — readings, gatherings, other events — that happens in my communities in November.

Reber: What’s your favorite/most irritating myth about Natives? How would you set that record straight?

Washuta: Most irritating myths: That our identities are based completely in what a DNA test might say about us (bullshit) or in what we present that’s in alignment with something someone saw in Thunderheart (bullshit) rather than in our relationships and our roles in our communities. I try to set the record straight every day by continuing to live authentically and visibly as an unapologetic Cowlitz woman.

I try to set the record straight every day by continuing to live authentically and visibly as an unapologetic Cowlitz woman.

Reber: What are some of the best resources to find Native writers and their works? Who are some Natives you read, in this country or others?

Washuta: Facebook groups and pages are good resources for me. I recommend following “IAIA MFA in Creative Writing” to see the incredible things our faculty and students are doing. Follow Daniel Heath Justice on Twitter — he’s a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and a writer, and he tweets the name of an Indigenous writer every single day. Read The Yellow Medicine Review, Red Ink, As/Us, and Mud City Journal.

Reber: What’s your favorite part of the writing process? In a Poets & Writers piece you wrote that perhaps it’s not daily word count that gets a writer where she needs to be. Can you elaborate on how writing entails more than marching the words across a page?

Washuta: It’s true — I’m not into trying to hit a daily word count, ever. I don’t write every day, but I know that if I have three days without distractions, I can write 10,000 usable words. I binge on writing time just as I’ve always binged on Tootsie Rolls — I’m an all-or-nothing person, and having large chunks of writing time allows me to become deeply immersed in the work, which facilitates the making of connections between personal and public that come up throughout my work. Bringing together documents and fragments from American pop culture and history with my own experience, and being an edit-as-I-go writer always seeking to get the first draft to be stellar, makes for a slow process for me.

In the Poets & Writers piece, I talked about the fact that writing breaks are important for me in protecting myself from the process of working with traumatic memories. I have PTSD. I am resilient, but the work of remembering, uncovering, and rendering traumatic experiences is still likely to be deeply triggering. Being triggered in this way has a very real impact on my life: I will be emotional and reactive, I’ll have brain fog, I’ll be exhausted, I’ll feel unsafe and insecure, and I’ll have a ridiculously heightened startle response that makes me jump out of my seat or choke on my food. The work that leads to this cannot be a part of my everyday life.

Reber: In addition to My Body Is a Book of Rules you also published the novella-length Starvation Mode. Many nonfiction writers don’t seem to be aware that that length exists. What are its benefits and, because “novella-length” irritates me with its inherent fiction reference, how might we nonfiction writers agree to some kind of neologism for it?

Washuta: I think the benefit of the short book-long essay — which is what I like to call it, rather than “novella-length memoir” — is simply that the size and shape of stories’ containers are incredibly important to me, as important as the content (or more important), and some work just needs to have a container that is smaller than the standard book and longer than the standard essay.

Your ultra-cool style of writing, which incorporates so many forms and hybrids and lengths, is so refreshing. How do you encourage other writers to enter the world of alternative/hybrid forms?

Washuta: Thank you! I think a necessary first step is to shift one’s thinking about what an essay is “about.” For me, essays like this aren’t just “about” the subject matter — the form is the content. It’s important to consider the significance of any presentation of a subject, whether that’s a traditional, chronological narrative structure or something in the form of a term paper. What’s the very best vessel?

Reber: There’s a doc on Netflix called Reel Injun that discusses Hollywood’s perpetuation of a certain Native narrative. Have you seen it?

Washuta: Yes! I used to teach classes on Native representations in film at the University of Washington, and I used Reel Injun often.

Reber: Some of the clips used in The Reel Injun are from Terrence Malick’s The New World. I can imagine how you feel about that film but would like to hear your words. Malick tries to humanize the native experience, and he shows European actions as ridiculous and barbaric. But the film isn’t merely centered in the politics of history. It’s exceptionally artistic. I think this, like the rest of his films, is a lyric essay set to film. It’s visually poetic, told in snapshots, up to audience interpretation. Have you noticed that?

Washuta: It’s been a couple of years since I watched The New World, and I’m sure I’d have a lot more to say about it if I were to watch it again — but what I remember most about the film is that it’s long, pretty, and mostly without dialogue. The natural world is something to look at, something to appreciate for its aesthetic qualities. This is unlike any Native peoples’ views of the world that I’m aware of. While cultures differ quite a lot in land-based practices and stories surrounding them, I think a common thread is that Native peoples have long-standing relationships with the land — living on it, working with it, having a history with it, respecting different ideas of personhood embodied by it. Just looking at the landscape seems to me to be a practice brought here by settlers. Scrolling through a National Geographic digital image list has pretty much nothing in common with the act of going to the river for salmon ceremony because of a long-standing obligation to honor the gift of their lives that the salmon give us. So I see The New World as a piece of art that looks at the land (having been filmed, I see, very close to the place where the events took place) but can’t possibly embody the people’s relationships with that place.

I also think the silence in the film is a continuation of the representations of silent Indian maidens that have such a long and troubling history in film. I’m thinking of Sonseeahray in Broken Arrow, who eventually does speak quite a lot, but says very little when she is introduced as White Painted Lady, placed in the role of healing Tom Jeffords’s wounds while looking lovely. And I’m thinking of “Look” in The Searchers: she is mostly without a voice, she’s the butt of jokes, and Martin’s violent act of kicking her down a hill is meant to get laughs. And there’s Disney’s version of Pocahontas, too: she’s the protagonist of that film, and she does speak quite a bit, but when she meets John Smith, she has no words until she adopts his language. In all these roles, the Native woman is quiet, subservient, nice to look at, compliant.

The silencing of Native people has been an important tool of genocide: in boarding schools, Native children were forbidden from speaking the languages of home. Stories have been lost, and stories tell us how to live in our world: how to honor the beings with which we have longstanding relationships, how to treat one another, what to do and what not to do as human beings in order to live as well as possible. The replacement of these stories with silence is the replacement of old and durable ways of living and knowing with young, convenient, and untested narratives about “progress” and “improvement.” Native storytellers maintained these ways of knowing over many, many generations. So for a non-Native filmmaker to build his representation of a Native community from silence seems consistent with the erasure that has been happening for hundreds of years.

The silencing of Native people has been an important tool of genocide.

All that’s to say — I don’t remember the film, entirely, but I remember how it made me feel, which was uncomfortable. And so it’s possible that it is like lyric essay, in a way (although I think it’s a fiction, in that it’s not an accurate depiction), in that I think lyric essay relies a lot on reader effort.

Reber: Speaking of lyric essays, we talked earlier about alternative and hybrid forms. There are many nonfiction writers out there, even those who studied writing at uni, who remain unaware of forms such as the braided essay, the fragmented essay, the hermit crab, all of which are increasingly popular. You in fact write in some of these styles. Could you take a stab in explaining what these are and why you think they’re gaining in popularity?

Washuta: I think all these formal approaches to the essay rely on a heightened awareness of form (the visible shape of the text, determined by organization of its paragraphs, breaks, and other elements). Both the writer and reader are aware: in essays that most people think of as more formally “traditional,” I think the writer is often aware of the form but crafts the essay in such a way that the reader doesn’t have to be.

In many of these more fragmented or formally innovative essays, the form is as important as the content, and the two rely on each other. In my own work, I do make a lot of formal choices to create what people are calling “hermit crab” essays. I’m not sure where that label originates, but it might come from Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola, who write in Tell It Slant: Creating, Refining, and Publishing Creative Nonfiction, “This kind of essay appropriates existing essay forms as an outer covering, to protect its soft, vulnerable underbelly.”

I like that way of looking at these essays, but it’s not exactly how I think of the work. I think of form and content as vessel and contents held. My yellow bottles from the pharmacy are meant to hold pills, but I can also repurpose them to hold safety pins. I can’t use them to hold apple slices, because they’re not the right size. Similarly, I can appropriate the text form of the prescribing information that comes with those pill bottles, employing the direct address, elements of voice, progression of information, and other characteristic elements. I used that form in My Body Is a Book of Rules to tell the story of my own experience with prescription drugs. I don’t think it would be useful for holding contents that have to do with my experiences with online dating — I’ve used a different form for that.

I think this kind of formal innovation is gaining in popularity because people are encountering them more and more, in part because of online journals and digital resource sharing (like recommending essays via Facebook, which I see happening a lot). I think the more people see formally innovative essays, the more prepared we are with the tools to prepare us to learn an essay’s internal logic and rules, and we’re less likely to see these essays as weird failures because they don’t follow the rules. “Fragmented” used to be seen as a problem — now people are beginning to see that it’s a neutral quality.

Reber: Have you written any collaborative works? How do you imagine the collaborative works benefit the writers and the reader? Do you have any suggestions on how we/readers might start one? Most of the collaborations I’ve seen and read are from Julie Marie Wade and Denise Duhamel.

Washuta: I haven’t. I imagine that I’d be a terrible artistic collaborator. My writing process involves pushing myself further into traumatic memory than I think I can safely go without being completely overtaken by my PTSD, and simultaneously pushing myself to put that content into a container that’s more unusual than what I’ve come up with before (or at least as unusual). I can’t imagine subjecting anyone else to that, and also, the process is so personal and intuitive that I don’t think it would hold up if I let someone else in.

Reber: In your piece in The Weeklings called “I Am Not Pocahontas,” you wrote about that age-old question Americans like to ask: “How much Indian are you?” I love this essay because it reminds me of when I temped at a DNA firm in Sarasota, Florida, and received dozens of phone calls from people who believed if they could prove their Native heritage they would receive a bald eagle. It took quite a few of those phone calls to learn how to answer them without laughing. Yet on the other hand I could relate because I too wanted to verify what my father had told me about having Native blood. I do have some, a DNA test indicated, an infinitesimal amount that would, unfortunately for my mother, not qualify me as getting a full-ride to uni. Somehow having that confirmation, despite decades of my father telling me so, added another dimension to my existence. On the flip side I wonder about the times I’ve heard Natives banter friends or family members for not being Indian enough. What does that mean? How does one get to be Indian enough?

Washuta: There are so many different ways of being Native (enough) that it would be impossible for me to answer for anyone but myself. When I was in high school in New Jersey, where I didn’t know any Native people I wasn’t related to, I was anxious about being “Native enough” because there were white kids who questioned my authenticity and presented themselves as arbiters of Native realness. But their conception of Native authenticity probably came largely from Hollywood representations and from passed-around misinformation about what it means to be a tribe member — all that bullshit about Indians not paying taxes (so not true).

Now I’m an adult and I am very sure that I’m “Indian enough.” For me, that looks like enrollment in my tribe, which means that I have a formalized relationship with my community and am able to participate as a citizen. And it means having relationships within that tribe. And it means that I’m descended from people who lived in North America before settlers seized the land, people who have stories and land-based practices that have endured despite deliberate efforts by the U.S. government to eradicate our ways of living and knowing.