Lit Mags

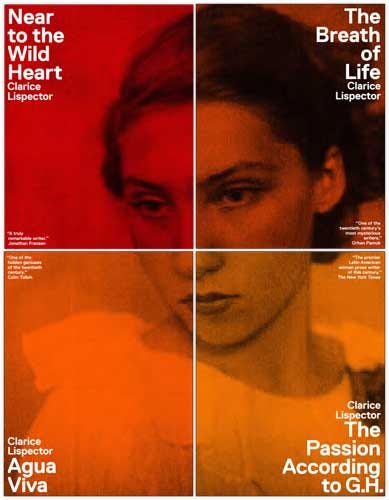

Near to the Wild Heart by Clarice Lispector

A story about trying to know your father and yourself

EDITOR’S NOTE BY BENJAMIN MOSER

When Clarice Lispector began writing Near to the Wild Heart, in March 1942, she was a twenty-two year old law student who had recently begun work as a journalist. Confused, “groping in the darkness,” she started by jotting down ideas in a notebook. To concentrate, she quit the tiny maid’s room in the apartment she shared with her sisters and brother-in-law and spent a month in a nearby boardinghouse. At length the book took shape, but she feared it was more a pile of notes than a full-fledged novel. “When I reread what I’ve written,” she said, “I feel like I’m swallowing my own vomit.” A friend, the slightly older writer Lúcio Cardoso, assured her that the fragments were a book in themselves. He suggested a title, borrowed from James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which Clarice had not yet read: “He was alone. He was unheeded, happy, and near to the wild heart of life.” A newspaper colleague recalled his amazement. “As I devoured the chapters the author was typing, it slowly dawned on me that this was an extraordinary literary revelation,” he said, calling her, “Hurricane Clarice.” He steered it to the book publishing wing of their employer, where it appeared with a bright pink cover, typical for books by women, in December 1943. A thousand copies were printed; in lieu of payment, she got to keep a hundred.

As soon as the book was ready she began sending it out to critics, and the reviews still bear witness to the excitement “hurricane Clarice” unleashed among the Brazilian intelligentsia. For almost a year after publication, articles about the book appeared continuously in every major city in Brazil. Sixteen years later a journalist wrote, “We have no memory of a more sensational debut, which lifted to such prominence a name that, until shortly before, had been completely unknown.” “The whole book,” critics wrote, “is a miracle of balance, perfectly engineered,” combining the “intellectual lucidity of the characters of Dostoevsky with the purity of a child.” In October 1944 the book won the prestigious Graça Aranha Prize for the best debut novel of 1943. The prize was a confirmation of what the Folha Carioca had discovered earlier that year when it asked its readers to elect the best novel of 1943. Near to the Wild Heart won with 457 votes. Considering that only 900 copies had actually been put on sale, it was a spectacular number. The unprecedented ovation that greeted Clarice Lispector’s debut was also the beginning of the legend of Clarice Lispector, a tissue of rumors, mysteries, conjectures, and lies that in the public mind became inseparable from the woman herself. In 1961 a magazine reporter wrote, “There is a great curiosity surrounding the person of Clarice. She seldom appears in literary circles, avoids television programs and autograph sessions, and only a few rare people have been lucky enough to talk to her. ‘Clarice Lispector doesn’t exist,’ some say.”

Benjamin Moser

Editor, Near to the Wild Heart, and author of Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector

Near to the Wild Heart by Clarice Lispector

Clarice Lispector

Share article

He was alone. He was unheeded, happy, and near to the wild heart of life.

— James Joyce

The Father…

HER FATHER’S TYPEWRITER WENT CLACK-CLACK … clack-clack-clack … The clock awoke in dustless tin-dlen. The silence dragged out zzzzzz. What did the wardrobe say? clothes-clothes-clothes. No, no. Amidst the clock, the typewriter and the silence there was an ear listening, large, pink and dead. The three sounds were connected by the daylight and the squeaking of the tree’s little leaves rubbing against one another radiant.

Leaning her forehead against the cold and shiny windowpane she gazed at the neighbor’s yard, at the big world of the hens-that-didn’t-know-they-were-going-to-die. And she could smell as if it were right beneath her nose the warm, hardpacked earth, so fragrant and dry, where she just knew, she just knew a worm or two was having a stretch before being eaten by the hen that the people were going to eat.

There was a great, still moment, with nothing inside it. She dilated her eyes, waited. Nothing came. Blank. But suddenly the day was wound up and everything spluttered to life again, the typewriter trotting, her father’s cigarette smoking, the silence, the little leaves, the naked chickens, the light, things coming to life again with the urgency of a kettle on the boil. The only thing missing was the tin-dlen of the clock that was ever so pretty. She closed her eyes, pretended to hear it and to the sound of the non-existent and rhythmic music rose up on tiptoes. She did three very light, winged dance steps.

Then suddenly she looked at everything with distaste as if she had eaten too much of that mixture. “Oi, oi, oi …” she murmured wearily and then wondered: what’s going to happen now now now? And always in the sliver of time that followed nothing happened if she kept waiting for what was going to happen, you see? She pushed away the difficult thought amusing herself with a movement of her bare foot on the dusty wooden floor. She rubbed her foot and watched her father out of the corner of her eye, waiting for his impatient and irritated glance. But nothing came. Nothing. It’s hard to suck in people like the vacuum cleaner does.

“Daddy, I’ve made up a poem.”

“‘The Sun and I.’” Without only a slight pause she recited:

“‘The hens in the yard have eaten two worms but I didn’t see them.’”

“Well? What do the sun and you have to do with the poem?”

She looked at him for a moment. He hadn’t understood …

“The sun is above the worms, Daddy, and I made up the poem and didn’t see the worms …” — Pause. “I can make up another one right now: ‘Hey sun, come play with me.’ Or a longer one:

I don’t think she saw it.’”

“Lovely, darling, lovely. How do you make such a beautiful poem?”

“It isn’t hard, you just make it up as you go along.”

She had already dressed her doll, undressed it, imagined it going to a party where it shone among all the other daughters. A blue car ran over Arlete, killing her. Then along came the fairy and brought her back to life. Her daughter, the fairy, the blue car were none other than Joana herself, otherwise the game would have been boring. She always found a way to cast herself in the lead role precisely when events placed one character or another in the limelight. She was serious as she worked, in silence, arms by her side. She didn’t need to be near Arlete to play with her. Even from a distance she possessed things.

She had fun with pieces of cardboard. She’d stare at them for a moment and each piece of cardboard was a pupil. Joana was the teacher. One of them was good and the other bad. Yes, yes, so what? What now now now? And always nothing came if she … there.

She invented a little man the size of her forefinger, wearing long trousers and a bow tie. She wore him in the pocket of her school uniform. The little man was truly sterling, a sterling chap, had a deep voice and would say from inside her pocket, “Joana, Your Majesty, would you be so kind as to lend me your ear a minute, just for a minute may I interrupt your busy self?” And then he would announce: “At your service, princess. Your wish is my command.”

“Daddy, what shall I do?”

“Go do your homework.”

“I’ve already done it.”

“Go play.”

“I’ve already played.”

“Then don’t pester me.”

She twirled around and stopped still, watching without curiosity the walls and ceiling that spun and melted away. She walked on tiptoe only treading on the dark floorboards. She closed her eyes and walked, hands outstretched, until she came to a piece of furniture. Between her and the objects there was something, but whenever she caught that something in her hand, like a fly, and then peeked at it — though she was careful not to let anything escape — she only found her own hand, rosy pink and disappointed. Yes, I know the air, the air! But it was no use, it didn’t explain things. That was one of her secrets. She would never allow herself to say, even to her father, that she never managed to catch “the thing.” Precisely the things that really mattered she couldn’t say. She only talked nonsense to people. Whenever she told Rute secrets, for example, she’d then get angry with Rute. It really was best to keep quiet. Another thing: if something hurt and if she watched the hands of the clock while it hurt, she’d see that the minutes counted on the clock passed and the hurt kept on hurting. Or, even when nothing hurt, if she stood in front of the clock watching it, whatever she wasn’t feeling was also greater than the minutes counted on the clock. Now, when happiness or anger happened, she’d run to the clock and watch the seconds in vain.

She went over to the window, drew a cross on the windowsill and spat outside in a straight line. If she spat once more — now she could only do it again at night — the disaster wouldn’t happen and God would be such a good friend of hers, such a good friend that … that what?

“Daddy, what shall I do?”

“I already told you: go play and leave me be!”

“But I’ve already played, I swear.”

Her father laughed.

“But there’s no end to playing …”

“Yes there is.”

“Make up another game.”

“I don’t want to play or do homework.”

“Well, what do you want to do?”

Joana thought about it.

“Nothing I know …”

“Do you want to fly?” asked her father absentmindedly.

“No,” answered Joana.” — Pause. “What shall I do?”

This time her father thundered:

“Go bang your head against the wall!”

She went off making a little braid in her long, straight hair. Never never never yes yes, she sang quietly. She had recently learned to braid. She went over to the little table where the books were, played with them by looking at them from a distance. Housewife husband children, green for the man, white for the woman, scarlet could be a son or a daughter. Was “never” a man or a woman? Why wasn’t “never” a son or a daughter? What about “yes”? Oh, so many things were entirely impossible. You could spend whole afternoons thinking. For example: who had said for the first time: never?

Her father finished his work and found her just sitting there, crying.

“What’s this about, girl?” He picked her up, looked unfazed at her burning, sad little face. “What’s this about?”

“I haven’t got anything to do.”

Never never yes yes. Everything was like the noise of the tram before falling asleep, until you felt a little afraid and drifted off. The mouth of the typewriter had snapped shut like an old woman’s mouth, but it had all been making her heart race like the noise of the tram, except she wasn’t going to sleep. It was her father’s embrace. He meditated for a moment. But you couldn’t do things for others, you helped them. The child was running wild, so thin and precocious … He sighed quickly, shaking his head. A little egg, that was it, a little live egg. What would become of Joana?

Joana’s Day

The certainty that evil is my calling, thought Joana.

What else was that feeling of contained force, ready to burst forth in violence, that longing to apply it with her eyes closed, all of it, with the rash confidence of a wild beast? Wasn’t it in evil alone that you could breathe fearlessly, accepting the air and your lungs? Not even pleasure would give me as much pleasure as evil, she thought surprised. She felt a perfect animal inside her, full of contradictions, of selfishness and vitality.

She remembered her husband, who possibly wouldn’t recognize her in this idea. She tried to remember what Otávio looked like. The minute she sensed he had left the house, however, she transformed, concentrated on herself and, as if she had merely been interrupted by him, continued slowly living the thread of her childhood, forgetting him and moving from room to room profoundly alone. From the quiet neighborhood, from the distant houses, no sounds reached her. And, free, not even she knew what she was thinking.

Yes, she felt a perfect animal inside her. The thought of one day setting this animal loose disgusted her. Perhaps for fear of lack of aesthetic. Or dreading a revelation … No, no, she repeated, you mustn’t be afraid to create. Deep down the animal may have disgusted her because she still had in her a desire to please and to be loved by someone as powerful as her dead aunt. To then walk all over her, however, to disown her without a second thought. Because the best phrase and always still the youngest, was: goodness makes me want to be sick. Goodness was lukewarm and light. It smelled of raw meat kept for too long. Without entirely rotting in spite of everything. It was freshened up from time to time, seasoned a little, enough to keep it a piece of lukewarm, quiet meat.

One day, before she was married, when her aunt was still alive, she had seen a greedy man eating. She had secretly watched his bulging eyes, gleaming and stupid, trying to not to miss the slightest trace of flavor. And his hands, his hands. One holding a fork with a piece of bloody meat (not warm and quiet, but very much alive, ironic, immoral) skewered on it, the other twitching on the tablecloth, pawing it nervously in his urgency to eat another mouthful already. His legs under the table kept time to an inaudible melody, the devil’s music, of pure, uncontained violence. The ferocity, the richness of his color … Reddish around the lips and at the base of his nose, pale and bluish under his beady eyes. A shiver had run down Joana’s spine with the sorry cup of coffee in front of her. But she wouldn’t be able to tell afterwards if it had been out of repugnance or fascination and lust. Both no doubt. She knew the man was a force. She didn’t feel capable of eating as he did, being naturally reserved, but the demonstration perturbed her. She was also moved when she read horrible novels in which evil was cold and intense like a tub full of ice. As if she were watching someone drink water only to discover her own thirst, profound and ancient. Maybe it was just a lack of life: she was living less than she could and imagined that her thirst required floods. Maybe just a few sips … Ah, that’ll teach you, that’ll teach you, her aunt would have said: never do it, never steal before you know whether what you want to steal is honestly reserved for you somewhere. Or not? Stealing makes everything more valuable. The taste of evil — chewing red, swallowing sugary fire.

Don’t accuse myself. Seek the basis of selfishness: nothing that I am not can interest me, it is impossible to be any more than what you are (nevertheless I exceed myself even when I’m not delirious, I am more than myself almost normally); I have a body and everything that I do is a continuation of my beginning; if the Mayan civilization doesn’t interest me it is because I have nothing in me that can connect with its bas-reliefs; I accept everything that comes from me because I am unaware of the causes and I may be trampling something vital without knowing it; this is my greatest humility, she figured.

Worst of all, she could scratch everything she had just thought. Her thoughts were, once erected, garden statues and she looked at them as she followed her path through the garden.

She was cheerful that day, pretty too. A bit of fever too. Why this romanticism: a bit of fever? But actually I do have one: eyes sparkling, this strength and this weakness, jumbled heartbeats. When the light breeze, the summer breeze, hit her body it shivered all over with cold and heat. And then she thought very quickly, unable to stop inventing. It’s because I’m still very young and whenever I am touched or not touched, I feel — she reflected. Thinking now, for example, about blonde streams. Precisely because blonde streams don’t exist, you see? and off you go. Yes, but golden flecks of sun, blonde in a way … So I didn’t really imagine it. It’s always the same old pitfall: neither evil or the imagination. In the former, in the final center, the simple and adjectiveless feeling, blind as a rolling stone. In the imagination, for it alone has the power of evil, just the enlarged and transformed vision: beneath it the impassive truth. You lie and stumble into the truth. Even in her freedom, when she chose cheerful new paths, she later recognized them. To be free was to carry on after all and there again was the beaten track. She would only see what was already inside her. Having lost the taste for imagining. What about the day I cried? — she felt a certain desire to lie too — I was studying math and suddenly felt the tremendous, cold impossibility of the miracle. I look through this window and the only truth, the truth I couldn’t tell that man, if I went up to him, without him running away from me, the only truth is that I live. Sincerely, I live. Who am I? Well, that’s a bit much. I remember a chromatic study by Bach and my mind strays. It is as cold and pure as ice, yet you can sleep on it. My consciousness strays, but it doesn’t matter, I find the greatest serenity in hallucination. It is curious that I can’t say who I am. That is to say, I know it all too well, but I can’t say it. More than anything, I’m afraid to say it, because the moment I try to speak not only do I fail to express what I feel but what I feel slowly becomes what I say. Or at least what makes me act is not what I feel but what I say. I feel who I am and the impression is lodged in the highest part of my brain, on my lips (especially on my tongue), on the surface of my arms and also running through me, deep inside my body, but where, exactly where, I can’t say. The taste is grey, slightly reddish, a bit bluish in the old parts, and it moves like gelatin, sluggishly. Sometimes it becomes sharp and wounds me, colliding with me. Very well, thinking now about blue sky, for example. But above all where does this certainty of being alive come from? No, I am not well. For no one asks themselves these questions and I … But all you have to do is be quiet in order to discern, beneath all the realities, the only irreducible one, that of existence. And beneath all these uncertainties — the chromatic study — I know everything is perfect, because it followed its fated path regarding itself from scale to scale. Nothing escapes the perfection of things, that’s how it is with everything. But it doesn’t explain why I get all teary when Otávio coughs and places his hand on his chest, like this.

Or when he smokes and the ash falls in his moustache without his noticing. Ah, pity is what I feel then. Pity is my way of loving. Of hating and communicating. It is what sustains me against the world, just as one person lives through desire, another through fear. Pity for things that happen without my knowledge. But I’m tired, in spite of my cheer today, cheer that comes from goodness knows where, like that of an early summer morning. I’m tired, acutely now! Let us cry together, quietly.

For having suffered and continuing on so sweetly. Tired pain in a simplified tear. But this was a yearning for poetry, that I confess, God. Let us sleep hand in hand. The world rolls and somewhere out there are things I don’t know. Let us sleep on God and mystery, a quiet, fragile ship floating on the sea, behold sleep.

Why was she so burning and light, like the air that comes from a stove whose lid is lifted?

The day had been the same as every other and maybe that was where the build-up of life had come from. She had awoken full of daylight, invaded. Still in bed, she had thought about sand, sea, drinking seawater at her dead aunt’s house, about feeling, above all feeling. She waited a few seconds on the bed and because nothing happened she lived an ordinary day. She still hadn’t freed herself of the desire-force-miracle, since she was a girl. The formula was repeated time and again: feeling the thing without possessing it. All it took was for everything to help her, to leave her light and pure, fasting in order to receive the imagination. Difficult as flying and with nothing beneath her feet receiving in her arms something extremely precious, a child for example. Even by herself at a certain point in the game she lost the feeling that she was lying — and she was afraid of not being present in all of her thoughts. She wanted the sea and felt the sheets on the bed. The day went on and left her behind, alone.

Still lying down, she had stayed silent, almost without thinking as sometimes happened. She glanced about the house full of sunlight, at that hour, the windows lofty and shiny as if they themselves were the light. Otávio had gone out. No one home. And as such no one inside her who could have the thoughts most disconnected from reality, if they wished. If I saw myself on earth from up in the stars I’d be alone from myself.

It wasn’t night, there were no stars, impossible to see oneself from such a distance. Absent-mindedly, she remembered someone (big teeth with spaces between them, eyes without lashes), saying very sure of his originality, but sincerely: my life is tremendously nocturnal. After speaking, this someone would just sit there, quiet as a cow at night; moving his head from time to time in a gesture without logic or purpose to then go back to concentrating on stupidity. He left everyone dumfounded. Ah, yes, the man was from her childhood and together with his memory was a moist bunch of large violets, quivering with luxuriance … Now more awake, if she wanted to, if she let herself go a little more, Joana could relive her whole childhood … The short time she’d had with her father, the move to her aunt’s house, the teacher teaching her to live, puberty mysteriously rising, boarding school … her marriage to Otávio … But it was all much shorter, a simple surprised glance would drain all these facts.

It really was a bit of fever. If sin existed, she had sinned. All her life had been an error, she was futile. Where was the woman with the voice? Where were the women who were just female? And what about the continuation of what she had begun as a child? It was a bit of fever. The result of those days wandering here and there, repudiating and loving the same things a thousand times over. Of those nights living on dark and silent, the tiny stars winking up high. The woman lying on the bed, vigilant eye in the half-light. The hazy white bed swimming in darkness. Tiredness slithering through her body, lucidity fleeing the octopus. Frayed dreams, beginnings of visions. Otávio living in the other bedroom. And suddenly all the lassitude of waiting concentrating itself into a quick, nervous body movement, a silent scream. Cold then, and sleep.