interviews

A Novella About Chilean History, Structured Like an Arcade Game

Nona Fernández, author of "Space Invaders," on reliving revolution 30 years after the fall of Pinochet’s regime

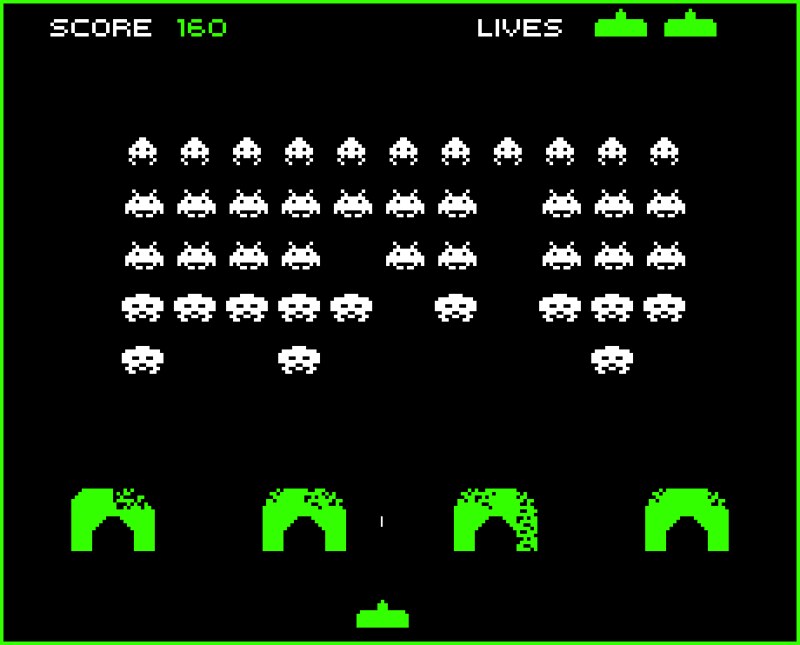

Nona Fernández’s novella Space Invaders takes its name and its physical structure from the 1980s video game of the same name. Those who grew up in that more pixelated era of gaming will recall the engrossing hours they spent killing off aliens on Atari or in arcades. Fernández’s book, an astonishing pastiche of dreams, memory, documents, and an episode of Chilean history which intruded into Fernández’s own childhood, is slender—a mere 64 pages—but it does invite the same level of obsessive attention, even long after its end, as the classic game did for many.

The novella, set during the dictatorial regime of General Augusto Pinochet in the 1980s, narrates in piercing little fragments the remembrances of a group of friends about a classmate, Estrella, the daughter of a military police agent. As opposition to the regime grows, Estrella disappears from the children’s lives. The unexpected turn in the novel’s final pages, which Fernández deftly delivers by leaping slightly ahead in time before the twist, is only part of what makes the novel stunning. Fernández’s vignettes contain multitudes in the way of historical, emotional, and psychic notes. There is, for example, the presence of a red Chevy, driven by Estrella’s bodyguard, “Uncle” Claudio. The car is a source of fascination for the kids, as well as a subtle point towards America’s intervention in the country’s political trajectory.

Space Invaders was first published in 2015. This year, the book—translated by Natasha Wimmer, who is also responsible for bringing the works of Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño (himself a fan of Fernández’s aesthetic) to English readers—was longlisted for the National Book Award for Translated Literature.

I interviewed Nona Fernández, an actor and screenwriter, whose many accolades include the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize, via email and through the translation generosity of Natasha Wimmer. We spoke about constructing a literary collage out of an interrupted childhood, not having to make up or imagine violence for fiction, and her hope for the current generation of young people engaged in protests against the Chilean government’s policies.

JR Ramakrishnan: The book is dedicated to Estrella, who is also your main character, and you mention Maldonado, another character in your novel, in the acknowledgements. Would you tell us about the personal history that informs the novel? From what I read, Estrella’s life mirrors that of the real-life daughter of one of the Caso Degollados agents.

Nona Fernández: The personal history of Space Invaders is the story I tell in the book. Estrella González was my classmate, like Maldonado and the rest of the chorus of voices narrating this dream or memory. Trying to write Estrella meant confronting my childhood, my experience as a student under an authoritarian regime, and my entrance into the world, the street. When I decided to tackle the subject, I gathered some old friends to share memories of Estrella and each of us remembered someone different, making it clear how arbitrary and personal memory can be. So the book grew to be about Estrella, our schooling back then, what it was like to be a child under dictatorship, how capital H History creeps into our small individual stories, but also how we remember when we remember; how we build collective memories; how we deal with fragmented, diffuse, and capricious memory; how we handle a collective memory that is the sum of many different versions.

JRR: Was fiction (as opposed to memoir) always going to be the form for this story? How did you consider the pastiche aspect of this work, especially the inclusion of the super endearing letters of Estrella? How long did the book take to come together as it did?

It’s sad to see how in Chile today, more than thirty years later, we’re living the same story again.

NF: The book was written out of wisps of air, constructed of snippets of dreams and memories, mine and others, like a collage, trying to account for the workings of fragmented, diffuse memory. Estrella’s letters are real. They were shaped literarily to make sense in the book, but the contents are what she wrote. I wove the materials together little by little. At first I thought it would be a story, but it got longer, and later the game—Space Invaders—turned up to give it a framework. I’d say it took about a year for the book to find its final shape.

JRR: Space Invaders, the video game, which structures the book’s sections and re-occurs in the text, made the novel feel like an ’80s period piece. Many people of a certain age have fond memories of the game but probably much less have had to deal with the trauma of the collective loss of innocence as your characters do. The book centers this trauma on the disappearance of Estrella, who happens to be connected to the regime’s enforcers via her police father. You also throw us back further into Chilean history with the reenactment of the War of the Pacific the kids do in school, and Space Invaders the game is about war too. Would you talk about the violence that permeates the novel?

NF: I’m part of a generation that grew up very exposed to violence. That was the context we grew up in and we were so much in the middle of it that we didn’t realize it. From the micro-world of our school—reenacting battles, raising flags, lining up daily in military formation to walk into class, celebrating the anniversaries of each of the armed forces—to the broader space of the country, full of death and human rights violations. When we realized that one of the killers in the Caso Degollados—which I write about in the book—was the father of a classmate, a man we knew, it became clear to what extent we had lived surrounded by violence in our innermost universe.

JRR: Related to the above, I was reading the news of the current protests in Chile and saw an item about how around 100 protesters were shot in the eyes and have been partially blinded. This detail brought to mind the most chilling line (to me) about Riquelme’s mother: “Crosses had been cut into her nipples with a razor blade.” The accessibility and mundane nature of a razor blade somehow made it the most brutal. How did you consider the specificities of the horrors of the period? Were they mostly from memories/reporting or were some dreamed up as fiction?

NF: It’s all real and it’s a part of what we lived as children. A compilation of collective memories. None of it is fiction, I’m afraid. And it’s sad to see how today, more than thirty years later, we’re living the same story again. We never really left it behind, I think.

JRR: Your book is being published in the U.S. just as Chile is dealing with human rights turmoil and mass protests. How does it feel to see this generation of youth (who have no direct memories of what Estrella and the rest of your cast went through in the ’80s) experience a version of the past? How does your novel, which was first published six years ago, seem to you in light of recent events?

Space Invaders is a metaphor for the children we were, exposing ourselves to the glow-in-the-dark green bullets of the military.

NF: President Piñera’s wife, Cecilia Morel, described the unrest in the streets as being a lot like an alien invasion. That single remark has made the image of extraterrestrial invaders very present these days in the streets of Chile. In my book, Space Invaders is a metaphor for the children we were, taking to the streets, exposing ourselves to the glow-in-the-dark green bullets of the military. Now that image is incarnated by today’s children. Children who aren’t afraid, and who don’t hesitate to stand up in the face of the future as glimpsed from our present reality. Their bravery is fierce and uncompromising, and they’re not open to dialogue. They don’t believe in it anymore and if it weren’t for their radical energy, none of this would be happening. Our children exploded: they decided to jump turnstiles after a fare hike; they decided to vandalize metro stations after a fare hike. The thirty pesos extra for the ticket was the culmination of thirty years of successive abuses that they’ve seen and see visited on their parents’ and grandparents’ bodies. They’re a new generation of Space Invaders. And all I can do is applaud them and do my best to take care of them.

JRR: The news made me think also of your meditations on time and memory. In particular: “Time isn’t straightforward, it mixes everything up, shuffles the dead, merges them…leaving us with no assurance of continuity or escape.” Do you feel hope for change in the contemporary situation?

NF: Chile is living a historic moment. I think we’ve never been closer to breaking out of the cycle we’ve been stuck in since the military coup. The arrival of democracy confused us, spun us around, and it felt as if we’d escaped from the lab cage where we’d been shut up like rats. But the military-written constitution that governs us to this day and the neoliberal system that was tested and implemented here have blocked any way out. All of this is in addition to a bland political class that has always given way to the military and to those on the economic right. That’s why we’ve been spinning in place for so long. Nevertheless, today we have the chance to open the cage and let all the rats out together. I’m optimistic and I sincerely hope that we achieve it. That we put an end in Chile to the abusive neoliberal system that got its start here.

JRR: Finally, would you share with us some of the new Chilean writing you are excited about?

NF: There are very few Chilean writers translated into English. But I can mention the names of three notable colleagues whom I admire and very much enjoy reading. Alia Trabucco (nominated for the Booker Prize this year), Lina Meruane, and Alejandro Zambra.