interviews

Norteño Culture & The Cowboy Bible

An Interview with Carlos Velázquez

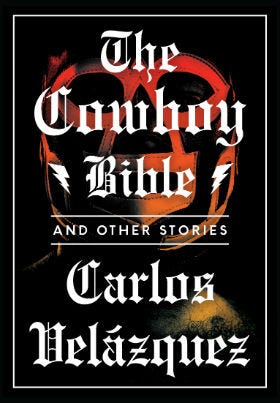

Reading Carlos Velázquez’s collection The Cowboy Bible and Other Stories (Restless Books, 2016) is a constantly shifting experience, moving through everything from absurdist realism to scenes that border on the mythic. His characters encounter everything from contemporary media culture to personifications of evil to intensely strong drinks. Throughout it all is the title phrase, which refers to everything from characters to objects in the stories contained within the book. Via email, I asked Velázquez about the origins of the book, the storytelling choices made within, and the region in which the book is set. His answers touched on perceptions of norteño culture, along with the works that influenced The Cowboy Bible, which includes everything from John Coltrane to Todd Solondz to Richard Brautigan.

Tobias Carroll: Where, for you, did The Cowboy Bible begin? Was it with the location, with the concept of running one name through a number of permutations, or something else entirely?

Carlos Velázquez: I’m atheist, but my favorite writer was Catholic: Kerouac. That’s what keeps me attuned to religious issues. The Cowboy Bible was born one afternoon when I saw a bible lined with bits of old blue jeans in a shop window, a practice that’s common. To protect their bibles, people have stopped covering them with paper and started using old jeans instead. This simple act encompasses the entirety of norteño culture. In the north, there’s a compulsive need to make everything norteño. From reality to the abstract, we reappropriate everything until it becomes our own. Covering a bible with jeans is the reappropriation of symbols that characterize the north. It’s not a completely innocent act, nor is it chance, it’s a subconscious impulse. If we could, we would put cowboy boots on the crucifix. It’s this exact idea that I had in mind when I wrote the story “The Post-Norteño Condition.” It’s a joke, but at the same time it’s an homage, to Lyotard’s postmodern condition. The way I see the world, if Lyotard had been born in the north, he would have suffered the anguish of being post-norteño.

…I needed a Los Angeles of the mind.

The fact that the bible is reincarnated in story after story follows one of the models I used while writing the book. In Trout Fishing in America, the book by Brautigan, all of the stories share the same protagonist. I chose two elements to appear throughout the book, the mix of classic mythology with popular mythology. For example, Los Cadetes de Linares with the Ipod. In this case I mixed Brautigan with David Lynch. Between Lost Highway and Mullholland Drive there are various reincarnations. I should clarify that for me classic mythology doesn’t mean the Greeks or even the Spanish Golden Age. It’s Leonard Cohen and Piporro. David Lynch sets his stories in Los Angeles because it’s a city where everything that’s unimaginable could happen. But I needed a Los Angeles of the mind. A territory that could fit Brautigan, Lynch, Burroughs, and that’s not something my geography could give me, or at least not directly. PopSTock!, where all of the stories take place, is similar to my town. But it’s just a representation, a product, that is, of the area where I live, which is one of the most interesting social laboratories in contemporary Mexico.

TC: On the second page of the collection, a footnote reveals that The Cowboy Bible is also known as The Country Bible; elsewhere, there’s a reference to The Country Bible also being known as The Western Bible. As you were writing this, how did one come to take precedence over the others?

Norteño culture is a product of identity that doesn’t belong to Mexico or the United States.

CV: It’s an exercise in Luddism. Although Mexico is part of the west, it’s always seen itself as part of Latin America, not to say that Latin America isn’t part of the west. Mexicans don’t think of themselves as westerners, but instead as Latinos, Hispanics, and Mexicans. In the north, where I live, the people don’t consider themselves Mexican. They are just norteño. Norteño culture is a product of identity that doesn’t belong to Mexico or the United States. It’s caught between the two, and it forms a symbolic third nation whose language is its nationality. There’s a misunderstanding in the center of the country with regards to the way we use language in the north. They think that to include anglicisms in literature is Spanglish, but Spanglish is a mix of languages that belongs to the children of Mexicans born in the United States. And that’s how the project of Chicano culture failed. That is to say that those kids aren’t completely gringo, but they are more so than they want to be Mexican. Therefore the literature that’s written in the north, and is sprinkled with English words, isn’t a hybrid between two languages. It’s the result of that limbo in which norteño culture is suspended and which is still being built. It’s because of the dynamic of language in this region. It’s alive and constantly changing in contrast to the Spanish that’s spoken in the capital, which is dead and hasn’t changed in decades. They speak the same Spanish there now as they spoke in the ’50s. The permutation of the bible is western, cowboy, cowgirl. It’s a way of responding to the notion that overwhelms us and pushes us to be western. It’s the feeling that we are in our own identity project and that we don’t yet know how to define ourselves, but as soon as we do, we’re sure we’ll belong to the west, and not to Mexico, the United States, or Latin America.

TC: One of the highlights of reading the collection is in seeing what form The Cowboy Bible would take from story to story. When you were writing these stories, did you figure out the placement of The Cowboy Bible intuitively, or did you write the stories without it and see where it would fit in the best?

CV: Although the book grew out of the premise that the bible would serve as the protagonist of all of the stories, each incarnation of it was not deliberate. The first story of the collection was the one that gave the book its name and the bible is a talisman. When I finished that story, each plot grew out of the next and everything came out intuitively. There was a lot of improvisation. While I was writing the book I sustained an impassioned romance with Coltrane. Thinking about it now, with some distance, it’s possible that was the inspiration for all of the reincarnations of the bible. I really like what I’ve written under the influence of Coltrane, but in particular the things that I’ve written impulsively. I see the bible as a record. For example, “Meditations” contains “The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost,” “Compassion,” “Love,” “Consequences,” and “Serenity.” For me, the bible in each one of its transformations is like a track on a record. The same criteria is used to connect songs as with the bible. My obsession with Coltrane diminished after a few years, but I can tell that my best pages were written under the influence of his music. In fact, now that I am finishing a novel that is linked to The Cowboy Bible, I’ve had to go back and study it again in order to figure out the keys to my own writing.

TC: What inspired the creation of PopSTock! as a setting for these stories, rather than using an existing location?

CV: PopSTock! originated from the section by the same name of the Spanish rock magazine Rock de Luxe. There wasn’t a single place that could represent the territory that I was imagining in my head with all of its norteño characteristics, and there also wasn’t a name that defined it better than the stock of pop. Because above all, The Cowboy Bible is a pop artifact. For the writers of my generation, literary influences are longer the only thing that we base our books on. There are other platforms, like TV series, comics, etc. In my case, music is one of the principle tools for creating my work. Understanding that pop culture, references, premises, and music all form a narrative layer that’s found on the surface and whose individual parts don’t mean anything at all is essential. Below the hypertext there’s a story. All of this is due to Joyce. Including PopSTock! itself. It’s my personal Dublin. I once read that all of the references mentioned in Ulysses would form a book as thick as Ulysses itself. I didn’t write a voluminous book but I set out to create a book formed on references that would tell a story. Without intending to, during my youth, I read authors who used reincarnation in their work. Characters are not the only part of literature capable of reincarnation. Territories and places where stories develop can also be reincarnated. San Pedro Amaro, San Perdosburgo, San Perdoslavia — they’re nothing more than what I saw in the work of Kerouac. In each book they take on a distinct alter ego — Sal Paradise, Jack Duluoz, Leo Percepied.

TC: Kevin Ayers appears in a footnote, a Manic Street Preachers quote serves as the epigraph to one story. How would you describe music’s relationship to your writing?

I was born in an unknown town in the north of Mexico that was a hotbed for postmodernism.

CV: I was born in an unknown town in the north of Mexico that was a hotbed for postmodernism. I dedicated myself to literature accidentally. In reality I wanted to be a rock critic, but in a town like mine it was a ridiculous idea. There weren’t many books to read, few things arrived from the capitol. While my contemporaries read the Latin American Boom authors, I devoured rock magazines, which all curiously made their way to my town: Rolling Stone, Kerrang!, Uncut, La Mosca, Conecte, etc. That’s what I grew up on. The book that got me into literature was Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller. I read it in high school when I was 15. Because of my interest in rock magazines, I’m unable to separate music from my narratives. It’s possible that I never would have become a writer if I hadn’t met my friend José Ramírez when I was 17. He was my brother and my teacher. He’s ten years older than I am and had already traveled around the country by the time I met him. When I discovered his well-stocked library, I moved into his attic and didn’t leave until I had read all of Bukowski and Paul Auster. That’s also where I discovered Pasto verde by Parménides García Saldaña, a work that was very important during my formative years. José was also a huge music-lover. During drunken evenings at his house I listened to many musicians for the first time including John Adams, Terry Riley, Luigi Nono, Mario Lavista, and Steve Reich.

TC: Your book is divided into three sections, “Fiction,” “Non-Fiction,” and “Neither Fiction Nor Non-Fiction.” What prompted this as a structure for the collection?

CV: I’m a fan of the films of Todd Solondz. Storytelling is traditionally divided into two parts: fiction and nonfiction. That was my model for breaking up The Cowboy Bible. In his films, Solondz plays a game. I repeated it, obviously with the same irony. Which stories could actually happen and which couldn’t, but I went beyond that. I created a category for stories that I believe don’t belong to fiction or nonfiction. So where do they belong? To a new way of telling a story. And just like with the references, they have value beyond their categorization. Stories that aren’t fiction or nonfiction border the supernatural, which is an important part of my culture. I don’t believe in witches, but in my region there are those who believe in them. What interests me is how stories can grow out of superstition. Above all it’s a lesson. It shows us how to tell a story. It’s a model. When I wrote the final stories in the Bible I was worried that I would be labeled a horror story writer. Or a science fiction writer, even though it’s clear that my stories don’t fit into that genre. So creating the section that was neither was what worked best for the book. It’s the only category that could fit some of my stories. Nobody would imagine that writing about a corrido singer who wants to sell his soul to the devil, or a singer who wants to become viper would be considered paying homage to Solondz, but it is.

TC: Early on in “Cooler Burritos,” you describe a bar that’s known for its “special brew.” Was there a real-life inspiration for that drink?

CV: There’s a very powerful drink in the north: sotol. It’s distilled from agave and from the same family as tequila. Historically, the Rarámuri people drank it, but it’s commercialized now. There’s a verse in “A Season in Hell” that says “to drink liquor like burning metal.” Ever since I read that line I’ve been obsessed with sotol. To cut its consistency of “burning metal,” many bars in my town serve it curándolo. They cut the intensity of it by mixing it with spices, fruit, and even cured meat. When I was writing The Cowboy Bible, I frequented a cantina called The Other Paradise. They sold sotol like this, known as grass, or crazy water. It was my inspiration for “Cooler Burritos.” For the people in my town, a good night of drinking can only end with cooler burritos. That’s why both of those things are part of the story. It’s also an homage to two symbols that contribute to our norteño identity, like carne asada or cabrito.

TC: Do you have a particular favorite of these stories?

CV: No. They are all equally important to me. Though I do have a favorite from my second story collection: “El club de las vestidas embarazadas.”

TC: The Cowboy Bible was first released in Mexico several years ago. What was the reaction to it like there as opposed to the reaction to it from readers in the United States?

CV: That’s a hard question for me. I don’t really know what the reaction was like in the U.S. In Mexico the book received great critical attention. What could have added to that is the fact that norteños came to North American writers through the work of Roberto Bolaño. But Bolaño wrote based on speculation, The Cowboy Bible and the work of Élmer Mendoza (which is already translated into English) is the real literature of the north. It’s written from the north, not just about it. It comes from the same culture. It’s not a simple phenomenology based on the femicides of Juárez. It’s built on the language of the north.

— Translation between Spanish and English by Nina Arazoza