Lit Mags

Not a Bad Bunch by Anu Jindal

A story of whalers at sea

EDITOR’S NOTE by Benjamin Samuel

Boredom is dangerous. It can make us lazy, complacent, and if we suffer too much of it we’re liable to become boring ourselves. For the whalers at sea in Anu Jindal’s “Not a Bad Bunch,” boredom is far more insidious; according to the ship’s surgeon, who narrates the story, it’s an early symptom of an infectious and barbarous madness. The crew isn’t looking for trouble — they’re hunting for whales — but in such close quarters with few distractions, any transgression is cause for revenge. As the narrator observes, “A man breathing too loudly. One bad joke… All of us were forever at the seething point. Occasionally we spilled over.” Trapped on a ship with little to do but count waves and await the unremarkable “regular loveliness” of a sunset, boredom becomes a plague, a disease whose only cure may be destruction.

Of course, it’s not the boredom alone that makes these men violent. Violence is in their blood; they are a breed of men for whom an “eye for an eye” means they’ll simply continue their attacks blindly. These are men who drop an octopus in a boiling cauldron just to see what will happen, men who orgiastically kill a garefowl, an exotic bird and the last of its kind, only to be momentarily moved by their power to change the world. But the wonderment is fleeting. As they sail from one “arctic place” to another, it’s clear that it doesn’t matter where they go: they’ll never outpace themselves and their nature.

As the narrator describes the savage escapades of his shipmates, we realize that he, although of a higher station, is at best a man of questionable talents and dubious morals. He frequently interrupts his narrative to share the stories of brutalities committed by other men on similar ships, as if to make his crew seem better by comparison. Or if not exactly better, then to spread the culpability around to show everyone is at least a little guilty of something. For, as the title suggests, good or bad isn’t defined by actions alone, but how one’s deeds compare to the deeds of others.

But there is some innocence here, albeit in the form of a fetus the surgeon keeps in a specimen jar in his quarters. There is also a desire for redemption, if only to escape the doom they’ve certainly earned — a scene where lightning threatens to strike their ship becomes an opportunity for confession, in another scene the men pay tribute to a suicidal crew to ward off a similar fate. And there is even tenderness and love: a passion between two whalers ignited, of course, by a violent outburst.

Fortunately, for those of us in danger of succumbing to madness, this narrative is rich with the unexpected, some surprises coming from the men and others hauled from the deep. “Not a Bad Bunch” is a sea-faring adventure and a cautionary tale. So, for the sake of us all: alleviate your boredom and read this story now.

Benjamin Samuel

Co-Editor, Electric Literature

Not a Bad Bunch by Anu Jindal

Anu Jindal

Share article

One time, Stigsson, a lumbering, manic Swede, leapt while climbing down from the mast. Fifteen feet, blurred blond beard and soiled bare feet flagging in the air towards the deck, where he landed in a funny way. As it happened, a stray nail had been left behind where he touched down and it entered him through his heel, paralyzing his foot permanently so that he walks always with a kind of slump now. The sound of his hysterics reached me two decks below. When I came up I found him scrambling around, inflamed, raving, smearing bloody curves across the deck with his lame heel. I tried to dress his injury but he refused, reduced to a language of gurgled screams. In the days that followed, he stalked everyone on the ship, demanding to know who had left the nail behind, lacing his hands behind his knee to raise his leg and accuse them with the hideous purple wound. But who’d remember forgetting a nail? Who remembers the nails, crumbs, hair, flaked skin one constantly leaves behind? When no one confessed, Stigsson decided it didn’t matter who it was; he would strike indiscriminately, with the same unforeseen randomness which he’d been struck.

Several days later, as the deck boy was perched on the foremast, sewing a tear in the sail, Stigsson arrived with an axe and simply began to chip away, raging in some meaningless, private dialect. His intention was clear enough: he meant to drop the boy in the water, leaving him to drown, or else axe him directly if he climbed down. To sever a limb, a finger, toes, his head. It took four men to hold Stigsson back, and all the time he was lunatic, frothing. Spittle flying from his mouth, catching in his beard.

But I don’t want to give the wrong impression of our ship. Really this kind of thing did not happen often.

A week or so after Stigsson attacked the deck boy, another boy, the carpenter’s assistant, admitted to having left the nail behind. Who knows why he admitted it? He’d effectively gotten away. No one could have known or found out. Perhaps he believed Stigsson had spent his anger.

The assistant’s second mistake, besides confessing to Stigsson at all, was telling him in private. We found him in the morning, tied high up on the mast, shivering. His body had been scoured raw by the ropes, the rest pecked at by birds. He smelled deathly already; was hypothermic and dehydrated. “You’ll be back to strewing nails in no time,” I told him, though in truth there wasn’t a hope. He lay, platter-like, on the sick bay table and moaned. I asked, just in case, if he had family I could write to.

Without shame, Stigsson came to see what all the moaning was about, then wordlessly returned up to the deck above. At the time we were passing through an arctic place. Seawater flung up by the ship came back down as ice, chattering across the deck. Ice formed on the sails, around ropes, the inner workings of pulleys; on beards, knuckles, sleeves. Icicles made long tooth shadows, in sunlight and in lamplight, at all times, in all lights, against the deck and the sails. Stigsson moved around the ship, collecting, in a sinister way, icicles into a bucket. When he limped down again he pushed me aside, and — carefully rolling up the boy’s shirt — began laying ice down over the weeping sores and burns that deformed his body. The boy sighed each time an icicle touched him. Why hadn’t I thought of using icicles before?

“Goddammit,” I said. “Stigsson, are you a doctor? No — because I’m the doctor.”

Then Stigsson began to sing — his voice soft as serge cloth, his notes clear and musical as falling nails. Someone maneuvering a barrel across the deck stopped rolling to listen. It was the first time we’d ever heard Stigsson sing. Maybe the deck boy would be okay after all.

A certain amount of madness was tolerated on our ship. A certain amount expected. There were daily frustrations, encountered by everyone. Nails, splinters, burns. Boils, abscesses, infections. The constant proximity of others itself was maddening. And anything could be taken as a personal offense. A man breathing too loudly. One bad joke. The particular smell of someone’s natural oils or hair or ejaculate. One distinct, pestering laugh. The sight of yet another beard — somehow one beard too many. All of us were forever at the seething point. Occasionally we spilled over.

To relieve ourselves from the taxations of life, we had ways of peaceably passing the time (aside from the drinking, gambling, and fist fighting). There was fishing, of course, but even that could be taxing. Most of the time when a man fished he wasn’t really fishing, only standing stupidly with a rod in his hand. And the fish themselves were usually not interesting. You could expect the gills to fold and crinkle when you held one in your hand; the downtrodden mouth to puncture and gape, the bladed tail to kick. It was rare that a fish would surprise you. But occasionally — very occasionally — one deep-sea ugly would break the monotony. Something with no eyes, a beak, a lantern hanging in front of its face. Tentacles, an anus for a mouth, no bones. As if the sea were trying to purge itself, this thing would be handed to you, leaving you no choice but to murder it violently. In this way, fishing could become more of a burden than a diversion.

Once, for the sake of fun, the cooks set a cauldron of water to boil so that we could throw in a variety of things and see how they changed, or failed to change. We began with a coiled rope. It frayed apart and turned the water cloudy. Dried-out cheese became molten and disappeared. A tree branch stripped its bark completely. One of the ship’s rats sublimated into gas. We marveled at the cauldron’s destructive power, its hungry biblical willingness to destroy, like the grinding tidal suck of a wave from the dark Atlantic. We gathered around the cauldron like converts, entranced, feeding on its feeding. Inside its open mouth a tiny withered hand — souvenir from a tribe of the Amazon — blistered, before crumbling apart. A candle reduced to a wick and then nothing. Vials of blood turned various shades of black. Someone demanded the swollen fetus I kept suspended in a specimen jar in my sick bay, but I suggested the chemicals would eat through the cauldron if heated. (The fetus was pathetic already and didn’t also need to be boiled, his little body tucked into itself, as if he’d died cornered and beaten.) In his place, I presented to the mob a fold of unopened letters from my sister Josefine, which dissolved, satisfyingly, to nothing.

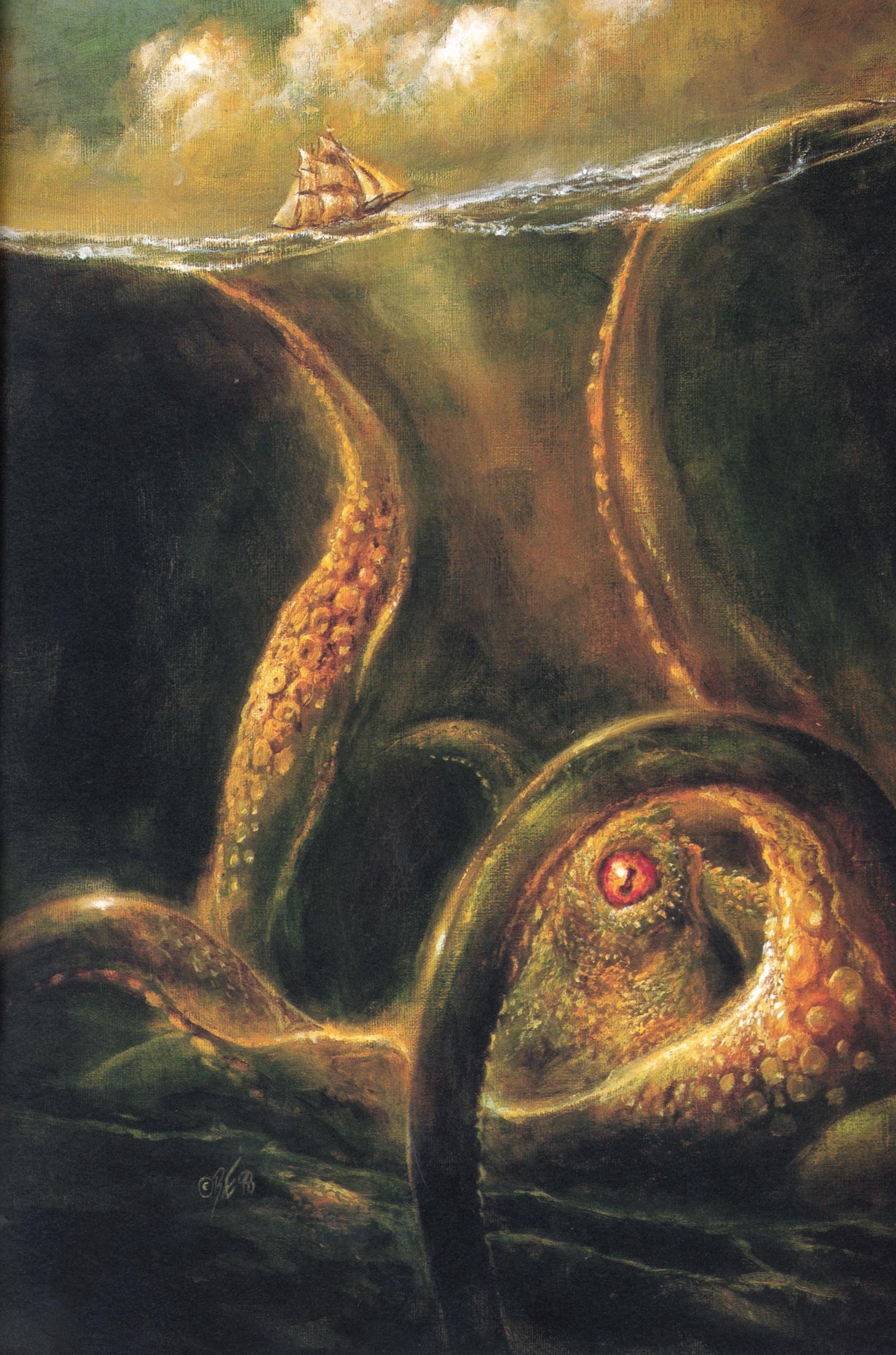

Drawing together, we finally set upon a whole octopus caught earlier in the day and contained in a live net hanging from the ship. But when we lifted it over the cauldron the animal managed to stop itself, tightly gripping the iron lip at eight points. Its bulbous head collapsed and stretched, beating rapidly, reflective with steam. It held itself high, dauntingly upright, flicking an accusing eye over each of our faces; the sound of the slick monstrous eyes like lips unsticking before speech. Finally, someone batted it over the head with an oar and it fell in, writhing and churning, jetting ink.

After that we threw a few more things into the cauldron, but most of us had lost our stomach for fun. We dumped the wet slurry over the railing — a witch’s brew of ink and fibers and unidentifiable flesh — and watched it all slide uneasily into the sea.

Sometimes we would travel far north, hunting for whales. In those latitudes we quickly got used to breathing ice, seeing ice, icebergs. We became accustomed to feeling cold and hated the thought of the humid tropics. Fungal skins and mosquitoes. Cannibal tribes with bones pushed through the septum. When the air was cold, one never sweat. You couldn’t smell terrible smells, and hardly felt pain. And in every port there were women to keep warm. Cold Prussians, cold Pomeranians and Poles. Volhynians, Scandinavians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians. Icy Jews. Frigid Gypsies. In the universal language they would pull us to their beds, imploring us to keep them warm — well, they didn’t pull me to their beds necessarily, but the other men were routinely pulled. In these lonely towns, where none of the dogs seemed to have a fourth leg, you didn’t have to point at a woman and ask, “How much?” The currency you needed was your burly heat.

Once, we heard the following story, inside a falling-down timber bar in one such lonesome, rat-patrolled northern town: several seasons before, a ship had also traveled far north, hunting for whales. But instead of whales they found themselves surrounded by heavy ice, which closed in, trapping them for the winter. Luckily they discovered a seal colony nearby to keep them fed, and enough wood to keep them warm until spring. But with the unremitting blinding light bouncing off the snow, and the uniform, blank whiteness, they very quickly became extremely bored. They suffered boredom like it was a disease. The seals were no fun to hunt; they just lay there, motionless. You could come up to one and pat it on its shoulder, and it wouldn’t even turn around. After the first month the men ran out of alcohol. After the second month they ran out of card games, and were tired of inventing new ones. With nowhere to spend it, the money just endlessly changed hands. Finally, someone left the ship and returned dragging behind a sledful of snow. The crew then proceeded to have a snowball fight. It lasted for thirty minutes. Once they had run out of snow, another man got the idea to pull out the ship’s supply of guns, gunpowder, and musket balls. The captain himself took up two pistols, and the crew resumed their fight firing loaded guns. Men chased each other through the ship, shooting. They climbed the masts, shot while peeking up from supply holds, from positions behind the pilothouse, shooting between fits of giggles. Eventually, when the ice had thawed away, the ship was found bloodily silent and full of holes. Some of the men were doubled-over as if in laughter, their faces balled-up; perfectly preserved.

This story stuck with us, in the form of a prophetic warning. We turned west, terrified by the idea of what the north could make us become. But our fear of collectively developing “snow madness” didn’t correspond in any way to reality. It was something else we wished to turn from. If a new boundary line is set that goes far out past the old boundary, it’s inherent in animals to occupy all the space that’s been allowed. Madness could not be much different. Our westward turn was in order to relieve ourselves from acknowledging an open question. If one of us went mad, what was there to stop the rest of us from following?

Once, in the middle of the night, a man dragged a knife over the tendons of another man’s ankles, to stop him tapping his feet while he slept. In return the tendonless man ground out the other man’s eye with the heel of a spoon. In retaliation for that, the first man nicked the fingers off of the tendonless man. This escalation continued until, eventually, they found themselves left ashore at the next port, no longer able to serve a useful function. Rolling limblessly from one end of the ship to the other did not constitute a function.

My suspicion about the true reason they were left behind, however, was that they’d made it possible for revenge to be taken that far. Warmed the men up to the idea, so that it might not seem so outlandish if another situation was escalated to the same extent. Once it happens once, it can happen again.

But that all took place on another ship. Not on ours.

Shortly after hearing the story of the ‘snow-mad’ crew and evasively pointing west, Stigsson spotted a pod of whales diving in the opposite direction. Waifishly small but also the first we’d seen in weeks. Despite our dread we turned to follow them, heading back north, where possible psychosis awaited. To combat our terror the captain suggested we give tribute to the crew that had died laughing, perhaps as a superstitious guard against madness.

Our tribute would take the form of a lantern topped with whale oil, lighted, sealed in a waterproof case, and lowered into the ocean by means of depth-marking rope. We waited for the next stormless day to gather solemnly at the side of the ship. Forty bent male heads with caps off in a semblance of respect. The captain began some words — which were promptly swallowed up by splashes erupting from below. Several huge creatures, with glittering white backs, moved around underneath us. They slid up, rose, fully emerged, churned, called out, slid under again. Each the length of a long glacial field, their bellows like a mountain collapsing. One of the creatures surfaced, directly beneath us, rising out of the water with our ship balanced on its back. The thing looked like a vast island. An island of porcelain, with fine hairline cracks and ragged, uneven scars. From this smashable height we could see the earth curving. There was nothing we could do. So far from home, no one would know. The captain loaded his gun and slid the barrel into his mouth, expecting the worst. With no women around, I was going to die in my twenty-third year and be an eternal virgin. The closest to sex I’d gotten was the smell the men sometimes came back with; and one time when, several years before, I asked a woman in my village with exceptionally milky skin and a bust so elevated it stood at her shoulders to marry me. She answered no, that she was already married, showed me the obvious ring, and I impotently had to continue seeing that milky bust for years afterwards around the village, causing me a deathly tight, unejected frustration in the region around my prostate, like a knot that you can’t untie.

I must have said some or all of this aloud, because even in the midst of imminent death some of the men — the captain among them, his gun covered in saliva — turned their faces to me and laughed. I felt the strain of the ship under our feet, and, an inch beyond my pelvis, the continued presence of my bitter unsexed knot. But soon we would all disappear.

Meanwhile, coins, pans, needles decked about — until the creature abruptly submerged again, and we were handed, humbled, back to the water. Despite holding our lives at its mercy, the monster hadn’t even realized we were there.

Once they’d passed, we went ahead with our planned tribute. Olaf, a harpoonsman, lowered the lamp down carefully, grip by grip. The captain resumed saying some words, but no one paid attention. At first, as the lantern crossed the surface, it seemed it might reveal to us the contents of the deep — decayed graves of shipwrecks; spired golden cities; other deeper, more ancient sea creatures. But then it hardly lit anything as it descended. Soon, it dimmed from sight completely.

Eventually, someone cut the rope.

Sometimes, the waters could be teeming with life. Sometimes, really most times, they appeared soulless and empty. Sometimes, in the middle of the night, a creature would call out across the plains of water, and you’d realize that while you slept, other life still carried on.

Sometimes, being surrounded by men didn’t seem that bad.

Once, we watched lightning strike across the water. Where it touched down, branches of light crackled out into the helpless water, blooming electrically. Small underwater fires. Each flash seemed aimed at us, engaged in a painstaking process of finding. Each interval between flash and sound grew slimmer, falling towards nothing at all.

While we waited in arrested panic, the young, still-recovering carpenter’s assistant mentioned an uncle in Gothenberg who had once used a tall rod to divert lightning away from his house. Following his instructions, Stigsson and Olaf lashed a fishing spear vertically to a skiff, and cast it out on the water behind us.

Scornful electric clouds slunk closer. The air felt tensed, alarmed, awoken by banging. Passively, we waited; we remembered tasks we’d left undone, memories we’d buried or forgotten. Memories that had rested, dormantly unstirred for years.

Once, I’d killed a patient out of negligence.

Once, I killed a man who wasn’t a patient, and I can’t say if it was an accident or not. In that instance, someone — for fun or out of the ennui to which fun is closely allied — had tied a long rope from the boom rigging to be able to swing back and forth across the deck. Hanging from the rope, people thrust past like hairy pendulums. I made known how childish I thought it all was, until it came my turn. Then I took the dangling end to the port railing, from where I leapt, pulled forward by gravity — forward and out, over the starboard side, the ship shrinking behind as I reached the apex, the moment where everything is still and joy is maximal, before one is cruelly sucked back. I noticed as I returned that a man stood dangerously close to my path, on one side, icily staring in a way I didn’t like. Why with coldness? Why did they only look at me that way? What happened next I don’t understand. I must have unconsciously aimed towards him, with my heavy boots preceding me. Once I realized, I released the rope, but it continued without me on the same path, the balled and weighted end-knot striking him in the forehead. He fell on the spot, instantly dead. I’d never seen anything like that before. No blood. Like he’d made a decision to be dead. Later, out of medical interest, I tried to write a paper about the phenomenon, but it wouldn’t be possible without detailing how I had come to observe it. Why expose myself to ridicule, further opportunities for the world to look at me unkindly?

As death continued to approach, in the form of the lightning clouds, all the deck became silent, contemplative; not just me. As if each of us inwardly was being confronted.

Once, my sister Josefine confided that she didn’t much like me. We were young, I was younger. But this didn’t stop her from tirading, furiously resenting what she called my obvious weakness, my watered down, white liver, as she held down under her feet a goose I was supposed to martyr for St. Martin’s Eve dinner. I’d gotten used to Josefine complaining how I would go on undeservingly to do whatever I wanted, while she — evidently more deserving — could count only on the narrowness of either a good or bad attachment, robbed of power; of choice. “Our parents say I should pray to god for a good marriage,” she said, the bird struggling under her legs. “But there is no god.” The beak of the goose crackled as she applied her full weight onto it, defacing the innocent bird. Only after leaving home and securing my way onto a ship, posing as a fully licensed doctor — only then did I learn that the world is actually full of Josefines.

The encroaching dread of clouds finally brought our thoughts to a simmering point. Across the deck, there came a collective sound of sighing. When the lightning arrived, it struck the pole instead, setting the skiff on fire. We watched it, blinking, amazed; felt the averted heat. As the skiff harmlessly burned, the lightning moved on. At first there’d been nothing. Then flames, reaching out of the water like a visible pain.

One morning we were standing on deck, the crew performing some duty from their list of mindless routine tasks — counting the number of waves that hit the ship, or something, I wasn’t a sailor, though I liked to see the gliding rhythm of their work being done — when a pair of raised voices clawed up from below. A woman climbed from the hatch, stamping across the deck. It felt like seeing a woman for the first time. I awakened immediately out of my brain-stupor, blood humming, flying distances around the ship while I stood shocked in place. She looked a bit threatening, gnashing the air with her teeth, striding to the starboard side. Skogholm — the steersman and a young cousin of Stigsson’s — climbed up after her. Awkwardly, because his pants were open below his waist, his penis wagging dreamily from side to side. “A man has certain needs,” he was shouting. “Tulla, why are you here if not for that?”

All work stopped. Seventy-eight eyes followed her. Normally, each eye belonged to one single head, the head of the crew. But not in the presence of a woman. In the presence of a woman, the collective head dissolved into thirty-nine discrete male heads again, each with its own ideas. For this reason, women were not allowed on board the ship.

When Tulla reached the far side she climbed onto the railing, twisting her hair into a knot, then dove thirty feet down to the water. A cloud of her smell — bergamot, sweat, honey — lingered behind. Skogholm reached the railing too late to stop her. He stood, unable to swim, watching deliriously as she swam away, his penis stranded mopingly over the railing. Out of a frustration which must have been chiefly sexual, Skogholm gripped his shirt and tore it in half down the middle, then in succession both shirts below that. The hair! So much hair sprung from his body, like a creature driven by hunters from the woods. “A man has certain needs,” he howled. But Tulla had gained a fair distance by then, swimming with one ear pointed down into the water.

Skogholm stuck his finger into the chest of the navigator, Hermansson, who had the helm, and demanded he turn the ship around. Amazingly, Hermansson refused. Reaching into his pocket Skogholm took out his knife — and with a flick, this was the end of Hermansson. We continued to watch as Skogholm grabbed the wheel around the dead pilot’s hands, and forced it starboard — but too vigorously, breaking the control to the rudder. The deck boy in the meantime was trying to mop up the blood, still pulsing out of Hermansson’s neck. “A man has certain needs,” Skogholm shouted, snapping the mop over his knee. “Needs, needs!” The ship continued forward, throwing more ocean between us and Tulla. I could just make out her long, bare legs kicking up from the water, shrinking towards the invisible coast. Skogholm saw too, and reached a new level of hysteria. Veiny and towering, gripping the furred skin of his chest between his knuckles, he rushed to cut the sail lines and stop her from slipping any further away.

It eventually took six of us to hold him down. If we had managed to catch up with Tulla, I’m not certain what Skogholm would have done to her. What any of us might have done.

Little was said about Hermansson, our dead navigator. Little done. To be honest, no one was too sorry to see him go. I’d treated him several times for violent attacks from the crew. All were deserved. He had been a person who greatly enjoyed turning people’s screws. Whenever he smiled you would begin to feel unsettled, sure that he’d wronged you somehow. Physically unlikeable, with a face perpetually oily, and which moved too much. It was probable that he cheated at cards, though no one was certain. If they had been certain, they’d have cut off his hands.

When he was still living, Hermansson had dominated at the card table. Winning hand after hand, then losing, strategically, as if his luck had suddenly left him. Fretting in his chair, grimacing at his cards, shuffling his remaining coins together — before nonchalantly taking a deep pot, exposing as ridiculous the hope that your luck might be turning. He didn’t even care about winning. He only wanted to humiliate.

Once, after Hermansson had staked a large pot — including a necklace intended for Skogholm’s wife — the latter sailor simply pushed away from the table to leave. “I’m sorry, Skogholm,” Hermansson said to his back. “It would have looked nice sitting between those big bulbs of hers.” Hermansson’s eyes were laughing, but his mouth was tight, serious.

“Don’t fucking talk about my wife,” Skogholm answered.

“Oh? She’s a saint? Forgive me I didn’t realize. She’s too saintly for me to imagine?”

Hermansson shut his eyes, evidently to imagine Skogholm’s wife standing before him. “Does she always turn her back when she’s slipping out of her dress, Skogholm?” He clucked his tongue. “She’s no saint at all — just a little coquette.”

Skogholm threw his chair but struck the lantern above the table. Cards, coins, the shining necklace flipped over onto the floor. Men stood back, dipping in and out of the swinging light.

“How does she get her skin so creamy like that?” Hermansson said, still fantasizing. He hadn’t met Skogholm’s wife before, but seemed to have no trouble imagining. Listening with attention, I also began to imagine. “Skogholm! It’s like butter!”

Skogholm shot his arm out like a lance, but the pilot slipped inches from his grasp. “She’s purring Skogholm. You’ve left her alone too long, and now she’s turned from you. She’s out looking for some fun. Well… I’m lots of fun.”

In the process of evasively climbing the bunks, Hermansson turned men out of their hammocks. From one of the berths fell a pair of men, cuddled and sweating: Stigsson and the young carpenter’s assistant, something we’d long suspected and would continue to ignore. “Your wife still only has one breast out,” Hermansson said. “Nice breast. But clearly it hasn’t been getting enough attention. Looks a little sad. How do you leave a breast like that at home; all alone, unsucked?”

Medically speaking, I didn’t know how much more Skogholm could take. Though, truth be told, I didn’t want to intervene. A mystery was being revealed — the actions that a man should take, the reciprocation one should expect to receive.

“Still, I don’t have all day to get her out of this dress. I suppose I’ll have to use my knife… Oops! I cut her a little. There is a little blood. But, don’t worry, she doesn’t seem to mind. Actually, I think it’s excited her a little…”

Skogholm took his non-imaginary knife out, attacking the ropes that held the bunks aloft. The pilot’s hands remained dreamily curled under his chin. “‘There’s so much I’d like to do to you. Where do I even begin?’ she says. Like she took it right out of my mind! ‘Tut,’ I say.‘I’ll show you where to begin.’”

The bunks finally collapsed, like a dream ending. Hermansson landed heavily on the ground, rolled up inside the cloth hammock, harassing in a muffled voice:

“Skogholm, Skogholm! When you come home, and your wife’s all cut up, and pleasantly exhausted — now you’ll know who did it.”

There came the flash of a knife, a long gash along the hammock; blood projected everywhere, across the floor, the walls, the brass lamp, and finally fifty-four stitches. It should have been worse for Hermansson, but he’d managed to dog Skogholm into mental doubt. Although he’d never had actual contact with Skogholm’s wife, the vivid specificness of his descriptions managed to pull up a root. For the rest of us, they made evident that our pilot — so oily, so unlikeable — likely possessed a history of unwholesome fulfillment with a tide of women. I didn’t feel a pressing need to be attentive with his stitches, leaving him with a meandering, hopefully repellant permanent scar.

Afterwards, Skogholm slept unstirring for days, and woke a forgetful man. For us forgetfulness is critically important, vitally necessary. Without it, grudges between the men would sustain perpetually, until death, the chain of revenge pursued without end.

Although, to be honest, Skogholm was never quite the same after that. The business of Tulla aside, he’d also taken to burning, unread, any letters from his wife.

Once, I petitioned to have all the guns removed from our ship. We were basically fishermen, I declared, what need did we have of handguns, long guns, rifles? Our tools were spears, hooks, harpoons. Cauldron, and mop, and knife. Needle; compass; rope; sail. I spoke of a simpler time, appealed to their sense of maritime nostalgia; aimed to put tears in their eyes. Secretly, I felt that gun wounds were just too messy. They left gaping holes, broken suffering organs, ruptured apart by tiny metal lumps that were such a headache for me to remove.

My sound rhetorical argument was met by a wall of shaking heads, crossed arms. Someone shot a gun in the air to emphasize their disagreement with my idea. I was addressing a collection of stunned, immutable minds. “Alright,” I relented. “Fine, fine.”

“No,” they said. “You don’t understand.”

Someone forced a gun into my hands. As if it were a living thing, I held on with nervous concern. It seemed to demand my whole grip, heavier and also not as heavy as I’d imagined. Sharp sulfurous smells emitted from the chamber, stinging my eyes. They said I should aim it at something. Just try it out. They even clapped, chanted my name.

For the past three days we’d been haunted by a frightening bird. Satanic black, larger than a crow, wider than a cormorant. A junk-eater, waiting for us to leave bits of carcass behind. In the carcassless night it let out mournful, extended cries. A crazy wingspan, absurd, needing only to flap once every eight seconds to drift in the air like a ghoul.

I pointed my gun at its massive body, closed an eye. Rather than casting a fog over my mind, lulling me into a trance, I found the gun sharply crystallizing. Standing behind it made things exceedingly clear. Nothing could be more real: Man versus bird. Like a beautiful equation. Man plus gun equals Nature minus bird. The others around me nodded knowingly. Now you understand.

I pulled the trigger. The whole right side of the monster was simply brushed away. Amid raucous cheers, we watched as the spectral whooping bird twirled like a fan into the ocean; to become history, along with the rest of our wake.

Once and only once, while on leave in Frederikshavn, the men invited me to join them on a trip to the local brothel, Madame Stina’s.

Olaf, the two cooks, Jürgensen the carpenter, Skogholm, the deck boy, and I. Walking in loose and excited formation, from the docks, past the fish houses, to the decrepit edge of town. Frederikshavn, always depressing before, now seemed to glow with the anticipation of my unvirigining, the rooftops crowned with slanted light.

While the others graduated to rooms upstairs, I was led around the parlor by Madame Stina herself, following the sound of her apron, her pockets rattling with change. She assured there were many beautiful women to choose from. I couldn’t see them clearly, but I could certainly picture them, deranged with wanting. Their groping hands reached out furtively from the dark, verbally offering deliverance from the pain that was hardening under my belt. Previously the only topless women I’d seen were on the operating table, and they were usually already dead.

I could have been happy just to remain in this room, the center of so much topless attention, but one of the women took my hand. “Call me Elke,” she said, while leading me forcefully up the stairs. Years of anticipation, like the coiled turns of a tourniquet, gripped around my prostate. Finally, finally something that had happened to all the other men — even the deck boy — would lay itself open for me.

Elke’s room gave no indication of what sort of person she might be. A characterless space, presided over by a dirty mirror, reflecting at a downcast angle the top of the dresser, the lumpen bed. I sat down evidently too far from her, and she shifted closer, draping a bare leg over mine. “Do you want to tell me what you like? Or shall I come up with something?” She spoke in heavy Dutch syllables.

“Actually… I never — ”

“You never?” she said. Her eyebrows disappeared behind yellow bangs. “Then you like everything. Lie back… let me show you.”

Very rapidly she advanced towards my pants. In the other rooms loud happenings were already underway, seeming to accost the walls, our room. The horrible bed felt like a fist in my back. I lay sideways; closed, then reopened my eyes. She was watching me, dragging her dirty nails over my legs. “Scared?” she asked. I ignored her and pictured Skogholm’s wife — creamy, pure, being attended to by Hermansson. No, by me. Something in me sat up.

“I don’t have all day for you to get out of that bodice,” I said. “Take out your breasts.”

She hesitated. Surprised? Then she smiled, from one edge of her mouth, conspiratorially, and began slowly unlacing. “No, wait,” I said. “Let me.”

The smile stayed on her face. Encouraged, I bent to the floor and removed a knife from my boot; cutting, in one breathless motion, the laces holding her bodice closed. I nicked her slightly at the top. Oops! A pearl of blood struggled out.

“Ah! Be careful,” she said, suddenly incensed. “What are you doing?” She put her hand over the cut, smearing blood over her protruding breast. “Are you crazy? Little shit. Don’t do that again.”

Cutting her, seeing her blood, I didn’t experience the same excitement Hermansson had while describing it. Elke didn’t seem to like it much either. Unless — she was only being coy? Was I actually meant to keep going? It could be part of the performance; she was a submissive; these were only sham protestations. I would ruin my chance by asking. I listened as someone in the next room — I imagined the deck boy — grunted and finished. Perhaps she wanted more. Perhaps I had not gone far enough, as far as Hermansson or the others would have gone. Perhaps I was being obviously weak, watered down, white livered. I looked at the blade, which hadn’t got any blood on it.

Once, a man stubbed his toe while climbing from the hold onto the deck. His forward stumbling fall looked innocent, but the entire nail of his large toe tore from its nailbed, clattering away over the deck. Before this he had been considered graceful. Others at various times had characterized his grace as salient, hard, liquid, snakey, spidery, clever, unfeminine. He had been admired for his spotless grace while climbing, pulling, sleeping, rowing, eating. While talking, laughing, diving, spitting, coming. But apparently not while falling. While falling he looked just like anyone else: stupid with pain. Those witnessing his fall decided he might not be so graceful after all. Meanwhile the nailless man — in the midst of his pain and irredeemable, lost grace — contemplated whether to cut off the toe, or burn down the ship.

In the end he did both. This didn’t happen on our ship, though it easily could have. It happened on a ship which is no longer a ship. Of which nothing is left, but ashes on a seabed.

One day, Olaf, the harpoonsman, spotted a squat heavy land bird walking over the flat table of an island we were sailing past. I came onto deck to see the whole crew assembled, avidly watching it; Skogholm with a parchment unrolled at his feet. “The island wasn’t on Hermansson’s map,” he said. The captain handed me his telescope, asked in my opinion what I thought the bird could be. “Is it valuable?” someone interrupted. “Valuable? Oh, yes,” I said, collapsing the telescope. “A garefowl. That’s what it must be.”

No one had seen a garefowl in decades. The assumption was they’d all been wiped out, brought all-the-way extinct. As word got around, of its rarity and possible value, the crew went mad — out of scale with its cause. It had been a dull month, devoid of any action or incident. And no whales sighted in weeks. This fact had settled on the ship like a depression. We imagined, in some place far from where we were, fleets of ships glutting themselves on whales, more than they had instruments to kill. Right now, they were dividing up a historic catch; exultant and reveling. Meanwhile our instruments languished on the racks, slowly rusting. I doubt it would have mattered how valuable the bird actually was.

To work themselves up even further, the men rubbed cayenne across their gums, nicked themselves between the fingers. We dropped the boats, leapt down. The crew was never as close as when sharing in a collective rage; angry camaraderie. Once, our ancestors had blown through all of northern Europe this way, a lusty marauding wave, raping and pillaging into old age. Behind us, the innumerable white waves rolled in over the water, like endlessly twisted sheets. Somehow, everything came back to sex.

From the fringe we stood facing a stack of high rock, piled in ancient geologic layers. Even the wind, circulating around the island, sounded ancient; like wise, deep chanting. On one side, a colony of seabirds had constructed homes for themselves, dug into the sheer walls. They stood at the edge of their personal caves, bellies white and reflectively beaming, like solitary lanterns. Occasionally one bird would fly out then immediately circle back, as if forgetting why it left. The pointlessness of their behavior was infuriating. Possibly sensing trouble, they began to make swooping attacks on us, pecking our hands and faces.

This only enraged us further. We used their small caves as handholds to climb up, throwing the birds directly from their holes. I found a nest with a reliquary of small chicks, about ten of them. They shivered, looked severely underfed, asking blindly if I was food. Their insistent, nagging-chattering drove me crazy. I grabbed a handful and threw them down, watching, relieved, as they were silenced in the sea spray.

Topping the cliff, into the heart of a low cloud, it took us a moment to spot the garefowl. The bird watched our approach, apparently unconcerned. So placid, so stupid and trusting, it hardly even resisted as Stigsson lifted it up by the neck and strangled it to death.

After that, not much happened. The wind, climbing up the rock pile and over the island, flipped through its feathers, making it seem more dead.

In the cold dew and silence we shook awake from our collective dream of conquest. Visions of sacking and razing, women we’d hoped to lay bare. Blondes, brunettes, reds. The children we would deposit in them, our seed spraying across Europe forever. I felt a startled confusion as the fog receded, as when you climb down from the deck to your quarters to look for something, and realize you don’t remember what it was, wondering whether there was anything in the first place, more than a desire for something. What had brought us here? What had we been hoping to accomplish? We tried to return to our earlier feeling, the purpose, our certainty. It had left us somewhere; fallen somewhere below the ground. Jarringly recalled to life, we found that we were basically fishermen, orgiastically mobbed around a motionless bird.

I searched for ceremony in the moment. “It’s a garefowl, absolutely, for sure,” I said. Several heads nodded in agreement. “Possibly the last one,” I added.

“What do you mean, the last?”

“I mean, possibly, this is it. There are no more garefowls. There won’t ever be more.”

A chill moved through us. “Really?” someone whispered. We felt it: that the earth had unalterably changed; that we had changed it. In a way it was a privilege, to be present for the passing of something. It was monumental, in its own way.

I had to tilt my head to look at the bird face-on. How did it look to know? Did it know? Someone else stuck his arms out, in a mimic of the bird’s shrunken flightless wings. He flapped them slowly, his elbows folded, to try them out for himself. To feel for the animal; inherit its lost traits.

“That’s it?” he said eventually.

Once the spirit had moved through us, it was gone.

One evening, the sun squatted low over the water. An ordinary occurrence, regular loveliness. Beside us a hundred of points of light swam aimlessly under the surface: a school of sardines, struggling to stay ahead of our wake. They appeared, disappeared, appeared again, like tiny cuts in the water.

By morning we would be home, finally at the end of our whaling season. Two-thirds of the crew were ailing. Twenty with venereal disease, two with colitis, one from an enraged infected amputation. Four consumptives. One overrun case of Norwegian scabies. One slowly drowning from water on the lungs. Most, if not all, suffering from malnutrition. Most if not all from acute psychosis — the result of being clamped together in a too-small space for too many months at a time. And one abused, overworked doctor, hard-pressed to help them.

I had secluded myself in the sick bay for several days, huddled in sick sheets to keep warm, pining for home. Desperate to taste butter, milk, almonds again, to cut into a roast, eat non-dry meat. Smell something that hadn’t just come out of a man. To hold a newspaper. To read it unhurriedly, with coffee, a pastry, among others like me; in a salon or a café, amid conversation — intelligent conversation. Where I could be understood. With people of my class and station. To use a toilet again, a private toilet, freed of the stress of having to go publicly over the railing like the rest of them, animals. To walk and walk and walk and not have to end at a point or prow. To be sane again; civil. Perhaps meet someone. At least to find someone I could visit regularly. I would leave my knife at home this time.

The other men were dressing down the ship, cornering rats, stowing barrels, scouring the deck for our return. Meanwhile I gripped a mop in my hand, motioning feebly at a layer of blood soaked into the floor. It settled in the cracks and fissures and dried there, made a vivid impression in the planks, like bite marks. Like the nick I’d left on Elke’s chest, which she had refused to let me sew up afterwards.

Mopping at the blood, succeeding only in making more blood in the dilutive process, I heard a cry from above. It almost sounded like someone saying, “Hermansson,” invoking the name of our long-dead pilot.

I ascended to find Skogholm, bloodshot, spitting, pacing over the deck, splitting the railings with devastating kicks, meanwhile holding one of Hermansson’s nautical charts over his head, and shrilly screaming, “Hermansson! Hermansson!” like a dog in alarm, finally snapping my last nerve.

“Calm down you idiot,” I said.

He pushed his fist, the map choked inside it, flush against my nose. “I’ve never liked you, doctor,” he said. “With your good breeding. Your trousers pinched up your ass. I’d like to pop off your head right now. But then I wouldn’t get to see you killed along with the rest of us.”

“What the hell are you talking about?”

With escalating volume and blame-apportioning fingers, he suffered to explain: as vengeful insurance against his life, perhaps aware of how unpopular he was, Hermansson had taken it upon himself to redraw some or all of our sea charts, omitting or altering critical details, such as reef placements, ocean depths, whole islands, and other possible dangers. Without him we would have no idea what lay before us. In its sad brilliance, I suddenly felt the loss of Hermansson, his probable loneliness; the conversations we could have had, the possible friendship; and also wished that I had thought of it.

The sails had been shifted aside, the cloth drifting loosely, spilling wind. Perhaps in precaution. And yet somehow we were still moving forward. “I don’t understand. What’s going on?” I asked.

“See for yourself,” said the captain, handing me his telescope. His face looked pale, grim. A moment later he gashed his throat with a knife, blood leaking out between his fingers, as he gripped it instinctively. At this point blood had ceased to have any meaning. I thought of housepaint on houses, rain clinging to windows, sap dragged down trees — general categories.

Through the lens, a dam of obscuring fog rose ahead of us. Past this, the world was still waiting to be finished. It seemed to be aggregating, the fog; racing forward, by a mechanism I couldn’t understand. A whole moving wall — dissipating abruptly, but not in a normal way. It slid into the water, under the water like an endless tablecloth being pulled down. And we were on the table, moving in that direction. I felt the wind sucking towards a single spot. The light, swelling waves that had passed us reversing direction, sliding back. There was a horrible breathing sound, like a stone wheel being turned. The edge of the water simply fell away. The water had an edge, like a cliff. We’d been caught in a maelstrom. A monstrous whirlpool. Hollow, vast — dragging me, us, all of us towards it.

What had I done to make an angry, retributive god loosen the plug of the earth? I was a doctor. Not licensed, but essentially. I healed people, asked nothing in return. At most for gratitude or affection, affectionate devotion, which didn’t seem like much. Once, on another ship, a captain had hacked apart an entire first mate. And instead of being punished, he was practically rewarded. The two men had been friends, served together for decades. They’d planned to retire together to adjacent wooded cabins, visit each other daily so as not to miss their old days too much. Then the captain fell to thinking that his friend was planning a mutiny. Why? No one knew. He was a superstitious man. Sometimes that was all it took. Perhaps he’d seen something; heard something in the night. Out alone in the center of the ocean, sudden fears could make nightly visitations.

At random moments the captain would spring from his quarters, stabbing at the first mate with jerky, bloodless fingers. “I knew it, I knew it! You were planning something. Why now, after all this time? I thought we were friends.” The mate protested but the captain refused to listen, clapping his ears with either hand. At mealtimes he would fling food at his friend, tossing mutton or knuckled bones, fists of butter, hot knives, working through a baseless, undivertible rage. The first mate took it all quietly. He was a solid imperturbable man who laughed easily, and when not laughing, who looked deeply contemplative. Whenever he laughed his eyes would close, as if he were being taken away.

When the crew found him dead his eyes were also closed. His disembodied head lay flat on the captain’s favorite bone china plate, propped in place with several hard dinner rolls, which prevented it from rolling side to side. The mouth had been filled with soup, up to the molars. Fish soup, a semi-clear broth swimming with hacked carp, half-boiled potatoes, and soft, edible bones. A cork jammed in the neck had crafted the head into a tureen. Each time the captain dipped his spoon in, it clinked against the pearly front teeth; and again when lifting it out.

The captain remained leaning over his soup as the crew slowly filed into the room. “I never eat without my friend,” he said, with a chilling lack of emphasis.

Who can follow the twists and turns of the insane mind? They didn’t bother to try. Instead, they remembered times when they’d felt insane, and rather than punish the captain they chose to take pity, leaving him behind on some remote, equatorial island. To live peaceably among the natives there, among savages like him. Savage and free from any sense of guilt. Why couldn’t something like that happen to us? Although I complained sometimes, fundamentally we weren’t such a bad bunch.

We reached the edge of the vortex. Spray flung up was instantly snatched back. Sounds were pulled in along the air. I recognized them from impossibly distant places: from the shore, even from cities. Clopping hooves, hollow church bells, the crying of so many unloved women.

The water circled slowly into the void, a funnel continuing darkly. Crackled with unholy energy. A sail tore away, flickered over the mouth, was sucked down. Then the ship in its entirety: tilting forward, tipping to one side. How easily we could be swept away. How shockingly easy. And when we were so close to home. Among the stars you could almost make out the still points of houses, the lights from the houses. And the people there waiting, perhaps waving. Elke. Tulla. Josefine. They didn’t deserve to be kept waiting. We stood, watched, aware of our ability to do nothing. The prevailing feeling was disbelief, frustration. But this was just the coat our despair wore.

Only Skogholm was grinning, twisted towards me. Wanting me to understand that I would die with his insane smile filling my mind. Then, his grin seemed to weaken. His teeth flew out into the void, one by one, like small birds, disappearing into the water. As we drifted into the dark hole, our eyes braced against their sockets, the hair pulled from the roots, organs lifting. I held my arm to my face, the other hugged around a mast. The terrifying sound grew deafeningly loud. I saw the carpenter’s eyes go hollow, rolling upwards. Then his intestines rose out of his pants like a charmed snake, pulled out of him. Skogholm was entirely lifted, feet loosely swaying as he was plucked away. Without teeth it was difficult to read his expression. The rest of us turned to each other, pointlessly appealing for help. Some of the men held hands. What can we do?, we mouthed. The ocean was empty beneath us. The ship was disappearing under our feet.