interviews

Observational Acuity & Indefatigable Care: An Interview With Jim Shepard

Jim Shepard has been treating readers to great fiction for over three decades. To celebrate the impact his work has had on readers and other writers for so many years, Open Road Media has re-released five of Shepard’s earliest and long unavailable published novels, a real treat for those only familiar with works such as his acclaimed story collection Like You’d Understand, Anyway (nominated for the National Book Award in 2007) or perhaps 2015’s excellent and highly-praised novel The Book of Aron.

Shepard writes masterfully across so many seemingly different genres and subject matters, from dystopian political parables, to meditations on adolescent suburban life, to page-turning thrillers, all while deftly exploring the cracks and crevices of humanity through thoughtfully developed, complex characters. His recently re-released early novels (Flights, 1983; Paper Doll, 1987; Lights Out in the Reptile House, 1990; Kiss of the Wolf, 1994; and Nosferatu, 1998) all show evidence that the author had amazing writing chops from the start.

Shepard is also a teacher of writing, and the favorite workshop leader for many writers. He is generous in the classroom and in conversation, as can be seen in the following recent email correspondence, in which we discussed writing companions, the sparks for a story, and Shepard’s mysterious love of the Minnesota Vikings.

Catherine LaSota: Let’s start with that grand opening question: When did you know you wanted to be a writer? More specifically, when did you start writing, and when did you realize it was an activity you could build your life around (assuming you feel that way about it)?

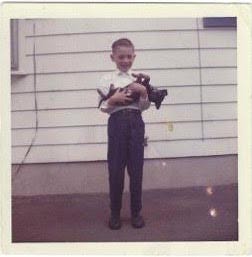

Jim Shepard: When I was a kid I never really believed I could be such a thing as a writer, since I was the first member of my family to go to college, and making a life as a writer seemed to me to be outside the realm of the sort of thing that people I knew did. I knew I loved to write, though, and to make up stories. The nuns at Our Lady of Peace, the Catholic grade school I attended, used to let us do whatever we wanted in English class after we’d diagrammed all the sentences they’d assigned, and I always used the extra time to write little stories involving monsters. I remember hoping that I would someday get some kind of job that would allow me to write like that on the side, and that maybe I’d also find someone to be with who’d like reading those stories. For a while I dreamed of being a veterinarian, and then discovered that they had other duties besides playing with dogs. I think I probably began to think of fiction as an activity I could build my life around only when I was an undergraduate, after I’d sold a few stories.

CL: In your recently re-released first novel, Flights, dogs are important side characters in the life of Biddy, the young man at the heart of the novel. Do you have pets yourself? What role have pets played in your life, and perhaps in your writing life, over the years? I know that my purring cat is often my only companion for the day when I have my butt in a chair writing at home.

JS: I’ve always had pets, starting out the usual way with goldfish and turtles. I got my first dog, Lady, for my first communion, after some passionate begging. In the photo of me holding her that day my grateful smile is so intense it’s terrifying. I’ve had a dog ever since, not counting a brief hiatus of three years I spent teaching at the University of Michigan. Right now we have three beagles. Dogs have always been hugely important to my writing life. They’re great resources for procrastination, of course, but they’re also happy and silent companions during writing time, as you note. And they’re wonderful models for observational acuity and indefatigable care. And of course, they’re also narratively useful: Amy Hempel’s version of Raymond Chandler’s old piece of writerly advice is, “When in doubt, have someone enter the room with a dog.”

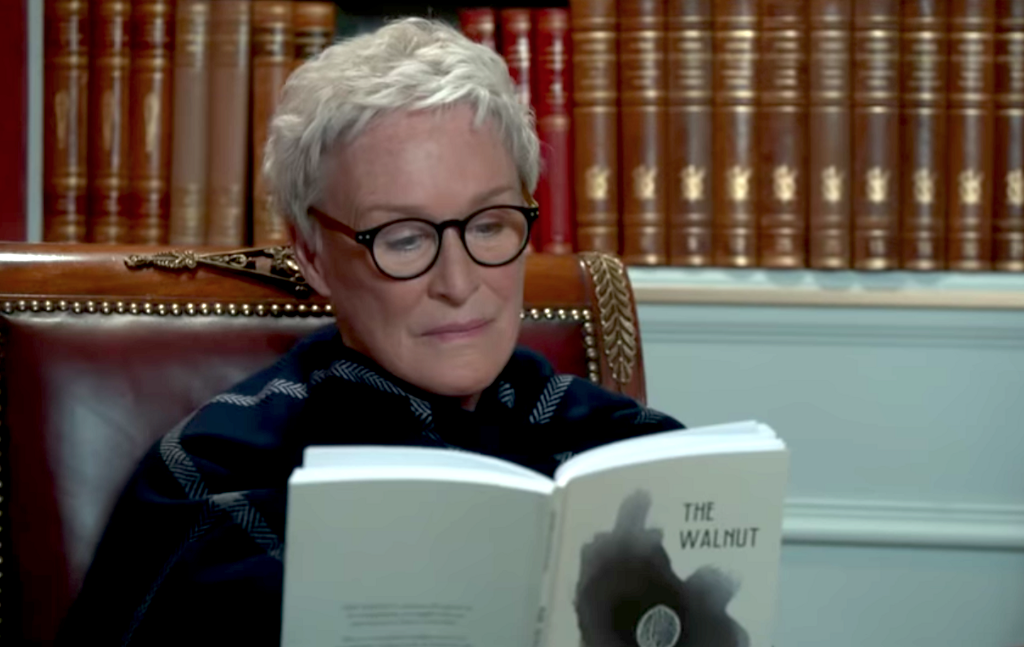

CL: I’d love to see that photo of you and Lady. Besides your dogs, is there anything else that you keep around you or your desk as you’re writing? Also — longhand or laptop?

JS: If by some miracle I can find the photo I’ll scan it to you. And as for my desk, well, it’s the envy of 10 year-old boys everywhere. Besides a big bulletin board on which I keep stuff from my research–images, maps, sketchy outlines, whatever–there’s a little tangle of prehistoric marine reptiles, and a megalodon tooth, and a full-sized bronze and horsehair replica of a Greek hoplite’s helmet. And I work on a laptop, but revise both on the laptop and on the hardcopy with a pencil.

CL: You are known as a writer who spends a good deal of time and effort doing research for the stories and novels you write. What first sparks your interest enough in a particular subject to research it intensely, and how do you know it’s going to be a subject that will lead to successful fiction writing for you?

JS: I’m always just reading weird nonfiction, along with whatever fiction and poetry I’m reading, in the hopes of turning myself into a more interesting human being. And every so often some situation or human dilemma within what I’m reading will catch my attention, and I’ll find myself continuing to turn it over in my mind. As in: what would it be like to be in that position? To have to deal with that? And once I find myself preoccupied with such questions, I’ll start reading more about the basic situation: the history or science or whatever. That second stage is me trying to figure out if I think I could write about such a thing. And if I start to think that maybe I can, then I start researching more systematically. Sometimes I’ll get a ways into such research before I finally have to conclude that I can’t write about it to my satisfaction, though, at least for the time being.

CL: Writers are really great at finding ways to procrastinate. How do you not research forever and ever — how do you know it’s time to start the writing?

JS: By reminding myself how prone to procrastinating I am, and by getting started once I have any sense at all of an evocative image or place with which to start, even if it’s the smallest corner of the world I’m trying to create: since it’s only by starting that I’ll find out more fully what it is I don’t know.

CL: So a story starts with an image or a place for you? Does it ever start with a character, or does that develop as the story progresses? How much do you outline, and how much are you discovering the story as you go?

…the process of writing the story is the process of teaching myself as I go.

JS: It usually starts with an image that conjures up a character in a place, and my sense of the character develops very rapidly from there. Or at least some central aspect of the character–usually having to do with the central conflict–develops if the story eventually works out. If the story’s heavily researched, I do some outlining of how I’m planning on deploying all of this information, and/or arranging all of these events, but I also recognize that if the story has any life to it at all, I should start to deviate from that outline, which was always by necessity skeletal and oafish, since I wrote it before I understood what I was doing. Since the process of writing the story is the process of teaching myself as I go. What’s that old line of Frost’s? “No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.”

CL: Many writers say that they can look back over a body of work and see that some of the same topics and obsessions have surfaced again and again in their work. In this way, the reader might come to see what is important to the writer and appreciate the scope of their work over time as they wrestle with their interests. What do you think are the things you come back to again and again in your work? I’m especially interested in hearing your thoughts on this considering the wide range of subject matter and time periods you cover in your writing.

JS: I’ve always been interested in how much trouble we can get into through passivity, and through complicity with more aggressive and powerful forces, or people. I’ve always been interested in self-destructive behavior, since we’re so good at it as both individuals and an aggregate. And connected to that, I’ve also always been drawn to catastrophe as a subject, particularly man-made catastrophe. And I was raised Catholic, so as my students will tell you, I’m relatively obsessed with the issue of agency: with that portion of responsibility that we have for what happens to us.

CL: You’ve taught undergraduates at Williams College since 1984. What is your approach to teaching writing and/or leading a workshop, and has that changed over the years?

JS: I focus as intensely as I can on close reading. I try to model how much fun that activity can be. I don’t patronize or set up a different set of standards for undergraduates. As for what’s changed over the years, I hope I’ve gotten smarter and more varied in terms of both my resources and receptivity.

CL: Are there any published stories that you particularly like to use as examples for close reading exercises in your workshops, and why?

JS: Oh, I use all sorts of stories. One author I almost always teach is Carver, because his work is so lucid on how much can be suggested by context, and on the kinds of options available to a story when it comes to communicating emotional information about recalcitrant and/or unreliable narrators. Another author I use a lot is Barthelme, as a way of shaking people who are just getting started out of their notions of naturalism as a story’s default position.

CL: You have four published story collections and seven novels, and you’ve served as an editor for several anthologies. How is the experience of writing short stories similar to or different from writing novels? Do you enjoy one form more or find one more difficult to write? How do you know if an idea for a story will be better suited to a short or long form?

…the story is more a guerilla action, while the novel is something like a full-fledged invasion…

JS: I prefer the experience of writing short stories, for a number of reasons: first, they allow me to do away with what I call all the furniture-moving involved in the set-up of novels–as though, to use a military analogy, the story is more a guerilla action, while the novel is something like a full-fledged invasion–and second because some of the sensibilities I try to imaginatively inhabit I don’t want to stay with for three or four years. Because of that, and in keeping with my general perversity when it comes to the marketplace, I’m always trying to see how short I can make something and still do it justice, and when, as in the case of The Book of Aron, I can’t see how to do it in under 70 pages or so, I assume that what I have in front of me is more likely to find its shape in a novel.

CL: Is three or four years a typical time frame for you to write a novel? How about for a short story? What are your strategies for prioritizing your own writing time along with teaching commitments and everything else life brings your way?

JS: A short voice-driven novel like Project X would take much less time to finish, in terms of a full draft, than a research-heavy third person narration like Nosferatu, which probably took more than twice as long. What are my strategies for prioritizing my own writing time? Ha! How about despair? Teaching at a place like Williams and being present as a parent and not asleep at the switch for three kids means long stretches of not writing, which I’m sure has steered me away from novels and towards short stories, since if I have to set a project aside for a long stretch, once I return to it, the impulses that spawned it can read as incomprehensibly as those notes you jot down on your bedside table about a dream you had in the middle of the night.

CL: You are a big fan of movies and other media, and you teach courses on film in addition to writing workshops at Williams College. How do movies inform your writing, and how does reading affect your movie viewing?

JS: Movies are inherently visual, and visceral, and not given easily over to rumination. In other words, they’re very good at showing us how we behave, and not very good at reproducing thought. I’m sure I’ve been affected by that.

CL: Some would say that television has become overrun with “reality” programs, but it’s also true that some of the most wildly popular recent television programs (and movies) have been inspired by books (Game of Thrones, The Hunger Games, etc). Why do you think this is the case? And what can television and film learn from literature? And how long until we see a serialized film adaption of the Ferrante novels, do you think?

JS: Television as it has evolved–and like everyone else, I think this is its golden age–is much more suited to books than movies are, since mini-series can more easily encompass the sprawl of novels. Before the recent revolution in television, if you wanted to film Ulysses, you had to do the whole thing in around two hours. And I would say two years, in terms of your Ferrante question.

CL: You are a fan of sports, which play a key role in Flights and subsequent stories and novels you’ve written. The Super Bowl, one of the most watched televised events in the country, will soon be upon us. The Minnesota Vikings are your favorite football team (you’ve even written an essay about it), yet you were born in Connecticut and went to school on the east coast. Why the Vikings? What similarities, if any, do you find between playing or watching sports, and the writing life?

Who knows how and why we imprint ourselves onto some teams, like baby ducks?

JS: Who knows how and why we imprint ourselves onto some teams, like baby ducks? How did I end up following the Minnesota Vikings, coming from Connecticut? As I say in that essay: Hey, what can I tell you. Bridgeport was a dull place to grow up. As for the similarities between playing and watching sports and writing, well, writers negotiate made-up worlds for made-up stakes and stage these simulations of pain and loss and revelation, the same way sports do.

CL: What does the phrase “the writing life” mean to you?

JS: I don’t use it, myself, but I suppose I take it to mean, when I do come across it, that gift that allows us to live in these made-up worlds–our own, and especially others’–as part of our everyday responsibilities.

CL: If sports are made-up worlds, and stories are made-up worlds, what then is reality, and how much time do you think humans actually spend there, considering how invested many of us get in these made-up worlds?

Anyone following our politics in 2016 recognizes that a dismayingly large portion of our electorate has chosen to spend nearly all of its time in made-up worlds.

JS: Anyone following our politics in 2016 recognizes that a dismayingly large portion of our electorate has chosen to spend nearly all of its time in made-up worlds. And the Balkanization of our corporate media has meant that they can stay there, hearing what they want to hear.

CL: The Book of Aron, your seventh novel, was published this year to much acclaim–it’s on a number of Best of 2015 lists, including this one here at Electric Literature. Has the experience of publishing and promoting a book changed for you over the years?

JS: Not so much. Not since my first book, when everything was new to me. Whether you get a fair amount of acclaim for a book or a book is ignored, you’re still keenly aware of what a tiny and ignored part of the culture in America literary culture really is.

CL: Do you think there is hope for literary culture enjoying a larger part of American culture in the future, or is there something inherent in the personality of this country that keeps literature marginalized?

JS: This country has always dealt with its own insecurities about its scruffy origins by proudly valorizing anti-intellectualism, and that’s only gotten more widespread and more extreme as our educational system has been undermined. I think there will always be a passionate group of readers and consumers of literary culture in this country, but they will always be swimming upstream against the dominant culture. It’s just a more pronounced–or much more pronounced–version of what goes on everywhere, though.

CL: Have you read anything recently that you’d recommend?

JS: Absolutely. If you’d like to hear how narrowly we avoided catastrophic accidents with nuclear weapons, check out Eric Schlosser’s Command and Control. If you’re feeling like a great thumbnail history of country music, I recently reread and loved all over again Nicholas Dawidoff’s In the Country of Country. And in terms of fiction, how about David Gates’ A Hand Reached Down to Guide Me and Lucia Berlin’s A Manual for Cleaning Women?

CL: What can we expect next from Jim Shepard?

JS: I’m only a story or two away from another story collection. You should imagine a small and listless cheer coming from the upper echelons of Knopf in response.