essays

On the Stories (Or Lack Thereof) of Joe Brainard

by Ravi Mangla

The writings of Joe Brainard can coax a smile from even the most wretched of misanthropes. While many forms claim him as their own, his words belong to no one discipline. To attempt to tag and classify them, to pin down the origins of his screwball musings, is to miss the point completely. His talent was too far-ranging to be limited to a single mode of expression. Poems, stories, one-liners, essays, lists, plays — nothing falls outside his repertoire. When Brainard died of AIDS, twenty years ago as of May, the world lost an artist whose utter bizarreness was matched only by his profound compassion.

Poems, stories, one-liners, essays, lists, plays — nothing falls outside his repertoire.

Brainard was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, at the base of the Great Plains, half a continent away from the young poets of Harvard (Ashbery, O’Hara, Bly, and the like), those precocious East Coast upstarts who would become the flagbearers for their generation. In many ways, Brainard lacked the blinkered ambitions of his literary counterparts. Like his drawings, his writing has a ragged, extemporaneous quality. The offhand delivery is laced with a lambent wit and odd poignancy. His peers figure prominently in his pieces, treading on and off stage like characters in a play. The charmingly concise “Ron Padgett” serves as a fitting ode to his oldest friend:

Ron Padgett is a poet. He has always been a poet and he always will be a poet. I don’t know how a poet becomes a poet. And I don’t think anyone else does either. It is something deep and mysterious inside of a person that cannot be explained. It is something that no one understands. It is something that no one will ever understand. I asked Ron Padgett once how it came about that he was a poet, and he said, “I don’t know. It is something deep and mysterious inside of me that cannot be explained.”

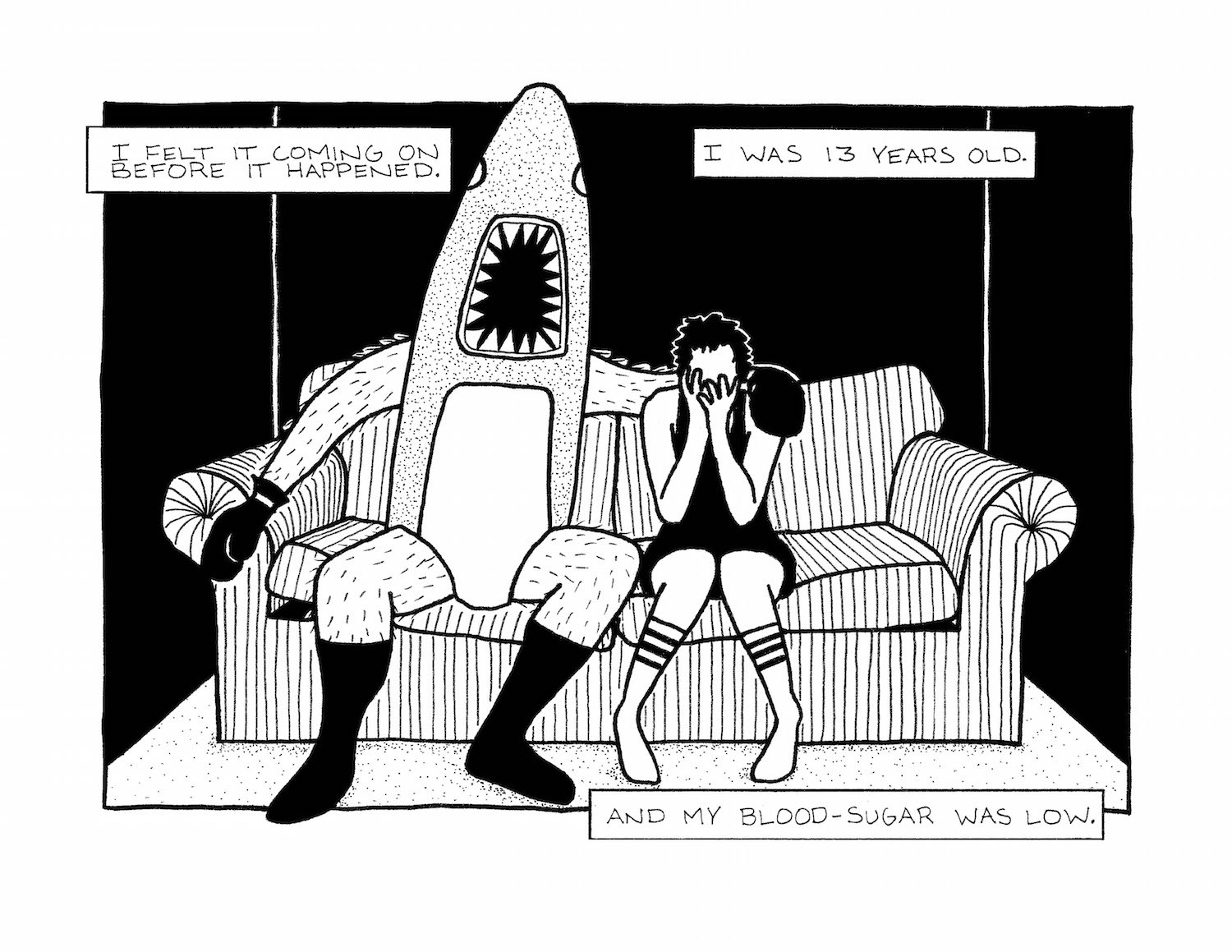

Brainard is remembered most notably for his lyric memoir, I Remember, in which each entry begins with the titular declaration. The recursive device, in its role as teaching apparatus for tenderhearted youths, has become almost a caricature of itself, yet reading the original — Brainard’s — resuscitates the form, returns it to a state of richness and novelty.

I remember once when I made scratches on my face with my fingernails so people would ask me what happened, and I would say a cat did it, and, of course, they would know that a cat did not do it.

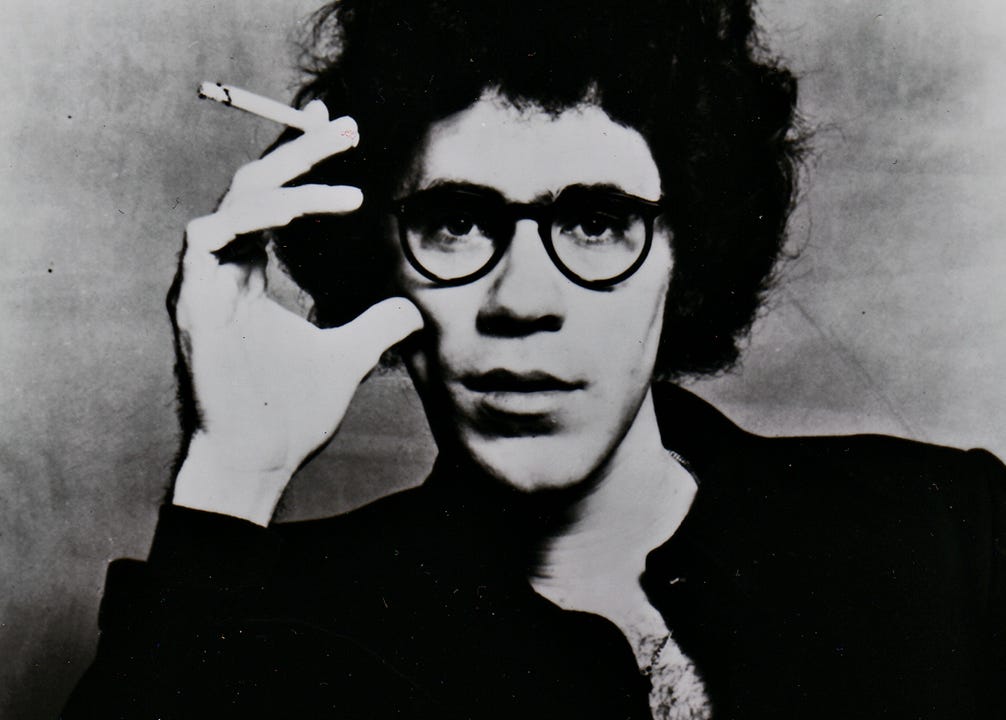

A visual artist by trade, Brainard was informed equally by the artists of his generation as he was by its cadre of writers. Certain pieces read like the sort of texts John Baldessari might commit to canvas, or Warhol inscribe in his journal. A feeling of glee underpins his mischief making. (The entirety of “No Story”: I hope you have enjoyed not reading this story as much as I have enjoyed not writing it.) His literary leanings derive less from a predestined purpose than his social proximity to other writers. During an interview with the late Tim Dlogus, Brainard states his surprise at the course of his career: “I had no intentions of being a writer; everything was against me. I had no vocabulary, I can’t spell, I’m inarticulate. I have sort of learned to use that.” Brainard crafts ingenious texts out of deceptively simple ingredients. His matter-of-fact tone and conceptual savvy make him a spiritual forefather to contemporary writers like Lydia Davis and James Tate.

For the last fifteen years of his life Brainard ceased making work for public consumption. (He would, on occasion, produce small works for family and friends.) Many have speculated on the reason for his withdrawal. In an essay written by John Ashbery for the Brainard retrospective at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, he mentions that Brainard spent the last decade and a half of his life immersed in his two favorite pastimes: “smoking and reading Victorian novels.” This description of Brainard’s later years contrasts sharply with the image of the artist as martyr, as the exemplary sufferer (to cop a phrase from Sontag). For the artist, the compulsion to create should supersede all other areas of interests. Anything less than absolute conviction is an admission of fraud. “There’s no retirement for an artist, it’s your way of living so there’s no end to it,” the sculptor Henry Moore once said. But this notion is an outdated pretention. The quality of an artist shouldn’t be measured by their unyielding devotion to the practice. Too often artists and writers are retrospectively punished for a lack of serious intent. (Without the ministrations of Ron Padgett, the writings of Brainard may have been lost to the onrush of time.) Brainard remains a singular artist of exceptional talent. That he found a source of contentment outside the bounds of art is not a blight but a blessing. By all accounts, he spent his final years absorbed in his passions, in the company of those he loved. We all should be so lucky.