Interviews

What Happens When Your Story Gets Too Big for One Medium?

The backstory of pulp punk band Dalton Deschain and the Traveling Show is three albums, three novellas, and growing

Sometimes a story is too large or unwieldy to fit in a single, discrete package. Maybe the narrative at hand is too far-reaching to be crammed into a single book, or even a series of books (or films or graphic novels or insert-medium-here); sometimes a story can only be told by weaving together multiple formats. Such is the case with Dalton Deschain and the Traveling Show.

Dalton Deschain and the Traveling Show is a story universe, a band, a series of novellas, and a narrative that is still unfolding at the time of this writing. The first part of the story to be released was Catherine (a book and EP), followed by Roberta (a book and EP), and this month they’re releasing their latest entry, Casey, which will be—surprise!—a joint book and EP.

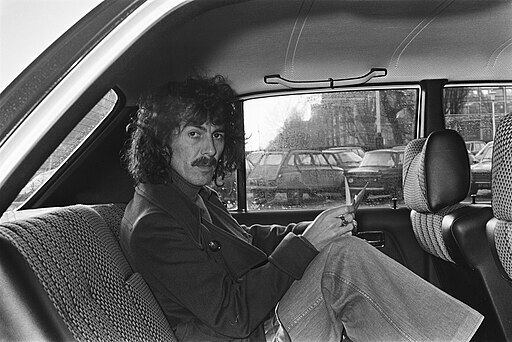

The titular Dalton Deschain is both a character in the story and a real-life human person, the latter of whom I sat down with to discuss this latest entry in the DDTS universe and the nuts and bolts of writing a cross-platform story.

Calvin Kasulke: I’m going to ask that you account for yourself on the record. Can you explain what Dalton Deschain and the Traveling Show is?

Dalton Deschain: We are a band. I think that’s first and foremost. We call ourselves a “pulp punk” band out of an aversion to genre labels, but also because there’s the allusion to pop punk, which we kind of are, but with pulpy-horror-sci-fi lyrics.

We follow a musician who is possessed by a demon who takes control of a circus and is a real bad guy.

We play regular rock shows but they tend to have a more theatrical bent to them, because all of our songs tell one continuous story about an alternate-universe 1940s United States after we lost World War II. We follow a musician who is possessed by a demon who takes control of a circus and is a real bad guy.

It’s this big, sprawling ensemble piece about circus “freaks” in the freak show and a demon and this girl that he sort of entraps into his orbit and a psychic janitor on the east coast—all these wild sci-fi horror elements just put in a blender, and that story is told through the music. We also release novellas with our albums that give you the entire story from front to back.

CK: How do you decide what part of the story goes into a song versus what goes into a novella?

DD: One of the first things I decided is that the songs needed to be accessible on their own, so if you weren’t interested in the story concept at all, you could still like the music. I don’t want to demand this dedication from every person that listens to the music, so I really wanted to avoid getting too in the weeds with the lore in the lyrics. There are some concept bands out there whose lyrics are just incomprehensible unless you know the whole story, and I definitely didn’t want to do that.

It almost comes down to the difference in opera between an aria and recitative, right? In an aria, it’s more a contemplative piece on the emotion that they’re feeling, while your recitatives are your less melodic, more fit-in-the-plot kind of things. That’s kind of where I draw the line: that these songs should be about primarily whatever emotional experience this character is going through in the scene, and that it should always be grounded in my reality or experiences. So I take whatever is happening to the characters in the story—whatever they’re feeling in that moment—and sort of write a song about both of us.

At the same time, I actually try not to cover the same ground in the story. Like in “Rabid,” which is on the EP, it covers the dog man’s traumatic relationship with a girl when he was in grade school. That’s not in the story. It’s kind of alluded to, but the way I see it, that ground’s already been covered in another section. If you know the music—which you probably do if you’re reading the book—you’re like, “oh, that’s someone in the song,” but otherwise it doesn’t detract anything from the story not to know that. I don’t need to spend five pages telling that story when there’s a song that does it already. I think they can sort of live together while each exploring their own little corners.

CK: Did you come up with the story first, and that then necessitated the band and the novellas? What was the order of operations in terms of creating the story, band and books?

DD: They fed off each other until they grew into an unstoppable nightmare. (Laughs)

Technically the story came first. I was writing music in college. I’d always wanted to write a concept album, but I never thought I would have an idea for one—I was like, “I just don’t have ideas.” And then I had this terrible nightmare this one night when I was a sophomore, and I couldn’t get it out of my head. I developed this story around it and I was like, “oh, I can make that a concept album.”

At the time it was way simpler. It was really two characters. It was Dalton and Catherine, and it was: Dalton is a musician. He gets possessed by a demon. He tricks Catherine into falling in love with him. He takes political power and hurts a bunch of people and something bad happens at the end. And that was it and I was like, it’ll be 12 songs and it’ll be done. I had the outline done, but I was in college and I didn’t have a band so I put it on the back burner.

When I came to New York I didn’t want to just drop 12 songs and be like, “oh, well that’s it, I’m done,” but have nobody listen to it because I hadn’t done any groundwork to get people into the story. So I started writing sort of auxiliary songs, and I would write a song and think, well how does this fit into the universe?

So I ended up writing about these characters and then the story got bigger. As I would write songs, new characters would work their way into the story and the story would grow and then they would introduce more new characters. Then they would introduce new songs and it all just kinda grew until I was like, “Oh I think I have like a very complete thing. I’m not adding onto it much anymore.”

The songs don’t actually tell the details of the story. They tell the emotional beats of the story.

As far as the books coming into it, that came in much later. Because the plan was still for it to all happen through music. It would just be a band thing. But as I said before, the songs don’t actually tell the details of the story. They tell the emotional beats of the story. And so people were interested, well, what is the actual story you’re telling?

I started writing these little journal updates I would send out to our email list—it’d be a little diary entry from one of the characters. But as I kept going, they kept getting longer and longer and longer until I was like, oh, this is too long for the mailing list.

But I was also starting to get more confident with every diary entry I wrote, I was like, well, actually this is much better-written than the one before. Maybe I can actually write this story. So that’s the idea for the EP trilogy that we’re concluding now, writing the novella for each of them, each focusing on a character—with the goal not yet to tell the entire story, but to introduce these characters. Once I was writing it, I was like, well this seems like the best vessel for it. We’ll write it like a series of novels.

CK: It sounds like everything you write helps inform the next thing you’re writing, not just in terms of the actual story, chronologically, but in terms of the structure of the next piece.

DD: Yeah, I’ve been figuring out the structure of this kind of as I go and every time I try something and I think it works, I go, “Oh we can keep going further in that direction.” I’ve definitely tried some things that didn’t work. The first email diary thing didn’t really work because it was too vague. People didn’t get a good sense of what it was.

Telling the story on stage has evolved a lot as well. We found a more narrative and engaging way of telling it that took years to find. I kept trying different weird little bits to try to make the storytelling palatable. And I kept trying to find obscure ways of doing it. I think I was afraid of telling it straight on. I thought I needed to find this abstract way of doing it, but it’s not what people wanted. Songs are the abstract way of doing it. People wanted to know, “Now just tell me the story, tell me what’s going on.”

CK: We should probably address that your name is Dalton Deschain, and also the villain of the story is named Dalton. When you had the initial dream in college, were you going by Dalton by then?

DD: No, I never intended to actually go by Dalton permanently. I named the character Dalton Deschain. As I was moving to New York, I was like, well, I should make that my stage name because when I perform, I have this character—not really grasping that when you move to a new city and start playing, there’s no wall between you and the audience. It was much easier for everybody to know me as Dalton, and so that just became the default.

CK: Talking about concept albums, are there other bands or artists or other equally confusing nouns that are influences?

DD: I mean, I’m a David Bowie fan till I die. I always wanted to write my Ziggy Stardust. Probably the biggest obvious influence is Coheed and Cambria, who told their story over multiple albums, but also did the supplementary work, like releasing novels of their albums. My idea was to take that Coheed approach and focus it a little bit more. It always felt like they were music first, and tried different approaches to tell their story—a comic book with one album, a novel with another. I wanted to find a way to more consistently tell the story from beginning to end.

I had, it turns out, a story that was being told in two forms simultaneously. And I had one of those forms figured out and I didn’t know what the other one was, but I kept pushing on until it found itself.

CK: And it sounds like part of figuring out how to tell the story was audience feedback?

DD: At the beginning I wanted to be mysterious about it. David Bowie never came out on stage and was like, “This is the story of Ziggy Stardust.” It was all kind of ethereal, and I wanted to do the same thing where I could say, “The story is about these things,” but it’s all in the music.

And people wanted more, they were like, “Well, what is that about? Who is this character? What do they do like, what’s the thing that happened?” I really wanted to be mysterious about it, but what I thought was coming across clearly wasn’t coming across. If what I think I’m conveying is not being accurately conveyed, then I need to find another way for it to be delivered.

CK: I’ve got a nice question and kind of a mean question. Which one do you want first?

DD: The mean one.

CK: Why not just write a musical?

DD: No, this is a good question. This is the question I get most often. Literally everyone’s first reaction when they see the band is “you should write a musical.” And that’s legit. I would love to write a musical. But a musical is a different form, and I don’t think this story fits in that form.

It’s not one-to-one analogous with a rock show that has theatrical elements to it. Some things bridge that gap like “Hedwig and the Angry Inch,” which is another work we’re very influenced by. But the story’s too long. If I want to tell this the way I want to tell it, hitting all these emotional beats and letting you follow these characters in this ensemble piece from beginning to end, we’re looking at 35 songs and that’s probably too big for a musical.

I want this to tell the story but also be a fun thing you will jam to in your personal life.

The songs have to serve another purpose as well. I want this to tell the story but also be a fun thing you will jam to in your personal life, and be at a rock show and dance to.

I like the idea of this being a surprise to people. I like people not knowing what they’re getting into—maybe they’re going to a show to see a different band, they’re not planning on a night at the theater. They go in and they’re just expecting a rock show and they get us. They get the fun high energy hooks and music and they also get this weird comic book thing going on, and there are props and there’s dialogue and things like that. That may translate to the stage in some version, but that’s not the primary thing we’re going for.

CK: The nice question is: What are the advantages and disadvantages to writing this way, in multiple formats?

DD: The advantage is, just on a superficial level, that it helps us stand out. There’s a lot of music out there right now, and with streaming you have immediate access to any song you’ve ever wanted. You can find a song you like on a playlist and that may be the only song you ever listen to from that band, because there’s no reason to really seek out more unless you’re really in love with it or you want to know more about that person or that band. You need to have something more than just the music now. We’re not just the songs we make, we have an entire universe that if you want, you can get lost in it.

The disadvantages are keeping it clean and organized in a way that’s accessible. I think we’re finally getting to a point where we do just have the music and we have the books, with the mailing list is as a bridge. You started one, you graduate to the other—but I think that can be confusing to people, where maybe they do discover us on just like Spotify and they’re like, what’s going on with this band? There’s a worry of being impenetrable, and finding a way to make it clear to people what it is that we do. You’ve got to find a way to make it cohesive across the board, that’s a disadvantage.

But I get to write anything I want in a bunch of different ways. It’s more freeing as a creative person to not just be like, “I have this next thing I want to tell, I have to make it a song. Let me find a way to make this a song.” Instead, I can make it a song, but maybe the idea doesn’t need a song. Maybe it’s just part of the book. Or maybe I just wrote a part of the book, and I’m really turning the scene over. Maybe then I’ll want to turn that scene into a song.

It’s almost like having a whole creative community in your own brain. You’re feeding off yourself. You’d be like, “Ooh, that thing you did is cool. Let me take a spin on that,” you know? But both people are me. It’s more avenues for creation, which can be overwhelming, but it’s also way more fun.