interviews

Patricia Engel on Florida, the Courage of Immigrants, and Writing a Novel of the Americas

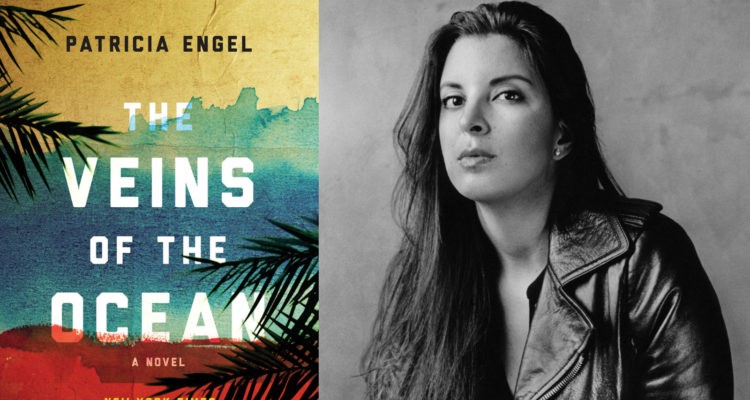

Patricia Engel’s new novel, Veins of the Ocean (Grove Press 2016), begins with one of the more arresting sequences I can remember. Whenever I’ve recommended the book to a friend, or a colleague, or anyone who would listen, rather than telling them what the book was about, or trying to explain why it was urgent to read now, at a time when our country seems hell bent on dehumanizing the immigrant (and first generation) communities that form its bedrock, I opened up my copy of Engel’s book and asked them to read the first page.

It begins:

“When he found out his wife was unfaithful, Hector Castillo told his son to get in the car because they were going fishing. It was after midnight but this was not unusual. The Rickenbacker Bridge suspended across Biscayne Bay was full of fishermen leaning on the railings, catching up on gossip over beer and fishing lines, avoiding going home to their wives. Except Hector didn’t bring any fishing gear with him. He led his son, Carlito, who’d just turned three, by the hand to the concrete wall, picked him up by the waist, and held him so that the boy grinned and stretched his arms out like a bird, telling his papi he was flying, flying, and Hector said, ‘Sí, Carlito, tienes alas, you have wings.’

Then Hector pushed little Carlito into the air, spun him around, and the boy giggled, kicking his legs up and about, telling his father, “Higher, Papi, Higher,” before Hector took a step back and with all his might hoisted the boy as high in the sky as he’d go, told him he loved him, and threw his son over the railing into the sea.”

You’re either the kind of person who reads those words and needs to read more, or you’re not, it seems to me.

But to give you more context, Veins of the Ocean is about Carlito’s sister, Reina: her love for her brother, who survived that fall only to repeat the same unspeakable act, years later, on his girlfriend’s son; Reina’s struggle to come to terms with her part in Carlito’s crime; her decision to leave Miami behind for the Keys, where she learns to free dive and works with dolphins and meets Nesto, a Cuban working odd jobs and saving up to bring his children Stateside. It’s at once a sprawling epic and an intimate story of one woman’s struggle to find some peace and a little hope.

Engel is a quietly commanding presence. She came into the EL offices on a recent Monday afternoon, after a final recording session for the audio book version of Veins of the Ocean. We spoke for an hour or so about life in South Florida, the story that inspired that chilling opening scene on the Rickenbacker Bridge, her research trips to Cuba, the courage of immigrants, and the way her characters’ lives, and her own, have been transformed by the Caribbean.

Dwyer Murphy: I want to start by asking about the opening section of The Veins of the Ocean, where your narrator, Reina, tells us about her family, and about Carlito. Can you tell me how that story — of her brother and the bridge — came to you, and how you went about crafting it into the novel?

Patricia Engel: The opening began as a short story that I wrote back in 2008, called “The Bridge.” I was with my mother one day, driving past a bridge, and she said to me, “A long time ago, a man threw a baby off that bridge.” She didn’t have any information, didn’t know when or how or why or what happened afterwards. She only knew that a man had thrown a baby into the bay. The image stuck with me, but I didn’t know what to do with it and I was busy working on my first book, Vida, at the time. I had no idea how to enter that story about the bridge, or even whose story it would be. Finally I sat down and wrote from the perspective of the sister of the baby who was thrown over, telling the story of their family and its collective trauma. I went on to write another book, It’s Not Love, It’s Just Paris, in the meantime, but that story about the bridge stayed with me. I always felt I would come back to it, though I didn’t yet know how.

DM: Did you eventually find out what happened? Were there newspaper clippings?

PE: No, I didn’t. I made it all up. But in the years since I published that story, people have sent me articles about incidents like that one. There’s a famous ongoing case in Tampa of a father who threw his 5 year-old daughter off the Sunshine Skyway bridge. Apparently it happens all too often, all over the world. Adults throw children from bridges.

DM: In narrating, Reina occasionally slips between English and Spanish, which enriches the language of the novel and also creates a sense of intimacy with the reader. Did you have a systematic approach as to when Reina would express something in Spanish versus English, or were you going by feel?

Some things are better expressed in Spanish…it’s natural to reach fluidly for whatever words best convey what you’re feeling.

PE: I write whatever feels true to the voice of the narrator. This is how Reina would speak naturally, as she is fully bilingual. Often it’s the way I speak naturally, too, and how my friends speak when we’re in our most comfortable element. You realize there are things you experience in your life that cannot be expressed in the English language, which is extensive and rich but not perfect. It has substantial gaps that don’t correspond to all the things we feel as humans. Some things are better expressed in Spanish, and when you have access to two languages, or more, it’s natural to reach fluidly for whatever words best convey what you’re feeling.

DM: This struck me as a distinctly South Florida book: the landscape; the ocean, which plays such an important part in the story; the Latin communities; the Keys. Was there something about the state that particularly inspired you?

PE: I grew up in the north, inland, nowhere near the ocean. I love the ocean, but I noticed when I moved to Florida twelve years ago that people who had the good fortune to grow up next to the beach view the world a little differently than people who didn’t. They experience life and the landscape in a different way. I wanted to tell a story that would show how that particular connection to nature and water develops. Also, I’ve always been interested in writing about specific communities and subcultures: how people find their communities and form new extended families when they’re taken from the world they know, when they’re displaced, whether it’s by immigration, or by some other kind of dislocation, or even a sentimental exile. In a place like Miami, which is a very expansive city but has so many different worlds within it, those communities are there, and they’re intertwined in a way they might not be in another city. From Miami, I moved the story south into the Keys, a place that’s even more distinctly situated: vulnerable to the elements, remote, and then to Havana and Cartagena. Those settings lent themselves to a different kind of story. I wanted The Veins of the Ocean, also, to be a novel of the Americas.

DM: The Caribbean comes into play, especially, when Reina meets Nesto in the Keys. She continues to narrate, but for long stretches we read Nesto’s history: his life back in Cuba, his childhood, his migration. I was wondering, where the Cuban community is so prominent in South Florida, and where the stories the community tells about its exile and its memories of home are so central to the culture there, did you feel any special pressure in crafting Nesto’s story?

PE: I’ve lived in Florida for twelve years, and I grew up with a lot of Cubans, who were like family to me, so I had a certain amount of second hand knowledge of their family histories. I also met somebody in Miami, a very recently arrived Cuban refugee, and the stories he told me were shocking and quite different than anything I’d heard before from longtime exiles. He was the product of a family who had stayed in Cuba and had experienced the revolution with all its highs and lows. He told me things I had never heard about before, in such detail, and he was the one who first encouraged me to look deeper into it.

But I knew I would have to go to Cuba myself. I couldn’t only do research from afar or rely simply on testimonials. So I went. I didn’t yet know what for exactly. I still wasn’t thinking it was for a book. I was just propelled by my own natural human curiosity, because I enjoy traveling and learning. But I kept going back. The more I went, the more I realized I would have to make even more trips, because there was so much to understand and I was barely scratching the surface. It’s an endlessly fascinating and complex country. The people are incredibly warm and have so much to tell. And at a certain point, I realized that because Reina’s character is so closed in on herself and is punishing herself in so many ways, it would be crucial for her to create a bond with somebody, in order for her to grow and fulfill her humanity. I thought, what kind of character could really reach her? It would have to be somebody who has endured a lot and with almost as complicated a past as she has; someone like Nesto. But I didn’t allow myself to be pressured into portraying life on the island with a particular slant or sympathetic to a specific point of view, as I would when describing any setting. Everything I have written about Cuba is absolutely true.

DM: This is also a story about the relationship between two siblings: Reina and her older brother, Carlito, who’s in prison, on death row, for having thrown his girlfriend’s child off the same bridge he was thrown from by his father as a baby. Reina’s life is so attached to Carlito’s, and their bond is so strong. It’s rare to find a book that’s so deeply about the brother-sister relationship.

How do you reconcile the fact that a person you love and have known all your life did something unforgivable…?

PE: It started because I wanted to write about incarceration and what that does to the family of the prisoner. They also have to absorb the consequences of the crime. As a family member, you’re free, you’re on the outside, but very often isolated by shame and blame, and how does that affect the love you feel for the person who’s on the inside? How do you reconcile the fact that a person you love and have known all your life did something unforgivable, committed this unnatural atrocity — throwing a child off a bridge, and in Carlito’s case, has lost the right to be alive? I considered who should tell the story of this man who, in spite of his guilt, is still human and worthy of our compassion, though he’s done this heinous thing. I decided it should be the sister who loved him best.

DM: Why did you want to write about incarceration?

PE: I’ve had some experience with it, and I’ve known other people who’ve also been affected by incarceration, not just as direct victims of crime but also the loved ones of people serving life and death sentences. I felt that incarceration gets portrayed as a single story in literature, in the media, and in our own popular consciousness. I wanted to offer something more. And it was on my mind, especially, because I live in Florida, which has such a corrupt incarceration system. Florida is one of the few states that still has death row and executes people regularly. That’s one of the greatest barbarisms of our country’s legal practice. And it’s not only the prisoners who are affected. There’s a long line of innocent people who suffer in different ways as a consequence of one person’s crime and the government’s punishment, and we don’t often hear about them.

DM: We’re in a particularly toxic moment in this country when it comes to issues of immigration, too. Latin communities, especially, are feeling the brunt of it. Your characters are very much of that world — Reina is first generation Colombian. Nesto was born in Cuba and is trying to get his children to the States. As you were writing, did you find this political climate affecting you?

Immigrants, whether they’ve arrived in their new country by choice or forced by circumstance, are the people I admire most…

PE: A general political and social disdain for Latin immigrants and their families has always existed in the United States, and has affected me all my life by virtue of being constantly reminded of my otherness and foreigness even though I was born in this country. But I started writing this book years ago, before this current phase of openly hateful anti-immigrant rhetoric was brought out so publicly and shamelessly. The times we’re living in now are quite unbelievable. I don’t write with a specific political agenda, but a human one, and a commitment to realism and truth. The fact is, I’m a daughter of immigrants and I grew up around immigrants, most of my closest friends are immigrants or the children of immigrants, and I still live in a predominately immigrant community. It’s the world I know and love. Immigrants, whether they’ve arrived in their new country by choice or forced by circumstance, are the people I admire most, whom I consider to be among the most courageous people in the world. I feel privileged to write about them in any way I can. With regard to the restoration of diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Cuba, I was as stunned as everyone else by the announcement. Had I ever imagined this new fold in history, maybe I wouldn’t have been able to write the story of Nesto, who was fleeing Cuba in a time when there was virtually no hope of change on the horizon.

DM: I wanted to ask, also, about religion. Reina isn’t somebody who goes to church on Sundays, but her life is touched by the spiritual: saints’ rituals and prophecies and, later, the offerings Nesto makes, and the belief system he was raised with in Cuba. Was there a story about religious development you wanted to tell?

PE: By the time the story starts, Reina, who comes from a Catholic background, mixed with some superstition and folklore, is a person who’s lost her faith. Yet Nesto, who was raised within a regime that systematically rejected religion, is full of faith. I wanted to show how people endure certain experiences, and some lose faith while others gain it, also how faith is so often tied to what we observe in our own families or communities. But faith is an ever-evolving thing, and open to interpretation. It accommodates our needs and the challenges life brings us. We can grow with faith or turn on it. Sometimes it comes back in unexpected ways. And, in the case of Nesto, who’s Cuban, I couldn’t ignore the fact that Afro Cuban religions are so prominent in Cuba, and there’s a great sense of the spiritual and divine being connected to the natural world. I did extensive research while in Havana to get those descriptions right, out of respect for the faith. In the novel, you see the unraveling of Reina’s past, and how she begins to piece together her own views of the world and beyond, deriving strength and meaning the more she grows connected to nature, and more specifically, to water.

DM: Finally, can we talk a little more about the ocean? In the Keys, Nesto teaches Reina to free dive, and a good deal of the story seems to be happening during those trips, underwater, essentially. Is diving something you’re interested in?

I always write for the person who knows more about something than I do. I want that person to feel like I got it right.

PE: I knew the ocean was going to figure prominently in the novel, as Reina’s and Nesto’s lives are controlled and transformed by the ocean in different ways. Personally, I’ve always been into scuba diving, but for my research I decided to take up free diving, too, took classes, and got certified. I hold myself to a tough standard with regard to research. I always write for the person who knows more about something than I do. I want that person to feel like I got it right. A lot of writers feel their imagination gives them license to write things however they want, but I know how it is to feel written about, as if a writer didn’t care much about getting things right, because they think their imagination takes precedence over reality, or else they’re just banking on the ignorance of their reader. So I’ve always gone overboard trying to get the details right, even for things probably nobody will notice. For this book, I spent a lot time many miles out in the ocean, throwing myself into the water with nothing but a wetsuit and my breath.

I don’t have a fear of the ocean, but free diving is very physical. There’s a lot of preparation and training involved. You’re limited by your body and can only go as deep as it lets you. But once you’re comfortable down there, being free of the noise and the tanks is a very special experience.

DM: What about dolphins? Between the boat trips, the dives, and working for a while at a dolphinarium, they feature pretty prominently in Reina’s story.

The Veins of the Ocean is an exploration of imprisonment in all its forms…

PE: In my years in South Florida, living in a seaside community, I’ve witnessed mass beachings of dolphins and manatees– sometimes from the red tide, and of course the oil spill. Soon after I moved here, I began volunteering with a marine mammal rescue organization. I spent many nights with dolphins in holding tanks, because they were disoriented and couldn’t swim straight, and we’d have to hold them, help them stay upright, and guide them along, keeping them in motion so they wouldn’t get water in their blow holes. I got to know people who dedicate their lives to that work, learned a lot about the line between animal conservation and captivity, and was deeply moved by the experience. The Veins of the Ocean is an exploration of imprisonment in all its forms; Reina begins to see parallels between the captivity and exploitation of the animals she works with and her brother’s treatment while in solitary confinement, as well as the ways the walls of her own life have closed in on her due to the burden of guilt she’s been carrying for her brother’s crime.

Originally published at electricliterature.com on June 2, 2016.