Craft

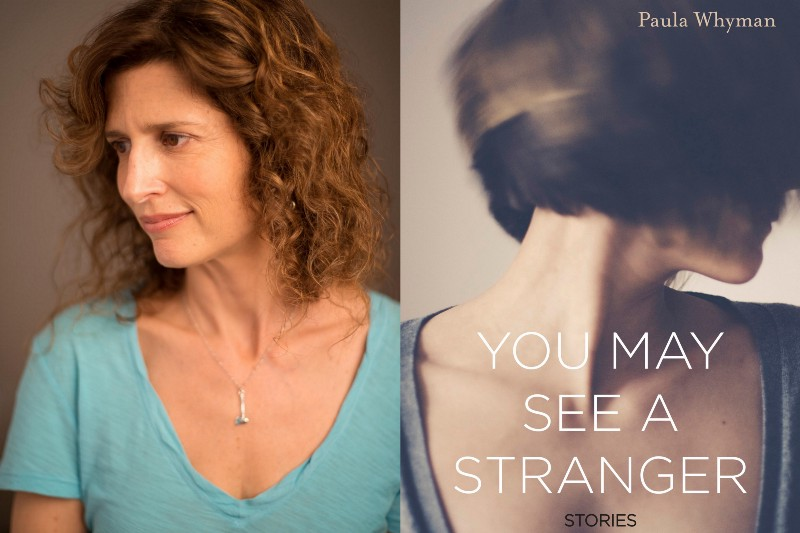

Paula Whyman on Motherhood, Linked Stories & The Inherent Humor of Sex Scenes

Michele Filgate Talks with the Author of You May See a Stranger

What are the moments that matter to a person, and how do they have a ripple effect on who that person becomes? In Paula Whyman’s linked short story collection, You May See A Stranger, the author focuses on one woman as she moves through different phases of her life. Miranda Weber is a compelling character, one who is equally capable of knowing what she wants and, as she gets older, trying to move past personal disappointments. I recently had the opportunity to interview Paula in front of a live audience at Book Culture for her New York City launch. After the conversation, Paula answered the same questions again via email.

Michele Filgate: Did you set out to write a linked short story collection?

Paula Whyman: When the first story in the book, “Driver’s Education,” was published by The Hudson Review about 10 years ago, I visited a high school in Harlem through THR’s writers-in-schools program. The students were eager to know more about the girl in the story. What happened next for her? I’d had no plans to write more about her, but I filed that question away. Then, a few years ago, I noticed I was writing stories that could be about the same woman at different times in her life. I decided to approach it intentionally. I had a residency at Yaddo coming, and I spent it working only on stories about this girl. I wrote drafts of two stories that ended up in the book. After that, I devoted myself to the project. As I wrote more stories, the book evolved; I’d initially planned to have different people narrate the stories, but as I went along, writing them all in Miranda’s voice seemed compelling. I never set out to write a novel about Miranda; I always intended to tell her story in this way, dropping into her life at these liminal moments.

Filgate: And I love how you do that! You follow Miranda Weber from adolescence to middle age. Was one time of life harder to write about than the other?

Whyman: The time when Miranda has young children, perhaps because those years can be such a blur. One tends to be, necessarily, more outward-focused. There’s not as much time or energy for introspection. Part of what I examine in that period is the anxiety that something bad is going to happen to your kids, and you can’t protect them. I think that concern is shared by most parents.

Filgate: Some of the stories are written in the first person and others in third. Was that a deliberate decision?

Whyman: Yes, it was. Two of the stories set when Miranda has school-age kids are written in the third person. In those stories, I sense that Miranda is distanced from herself, grappling with the partial loss of self that occurs, temporarily I think, when one has children. I’m not sure she handles it in the best way… I wish she were more focused on her daughter, for instance, in “Self Report.” She’s flawed, but I hope in a way that makes her human.

Filgate: Absolutely. She’s a very believable character. What does it take to make Miranda happy? Is happiness possible?

Whyman: Is happiness possible for anyone? I think we’re most satisfied when we’re meaningfully engaged. Miranda needs to use her better judgment, for one thing — and I think by the end there’s hope that she’s moving in a more positive direction. She’s also underemployed; she’s a “content provider” for at least part of the book. That isn’t supposed to be an inside joke. Well, it’s sort of a joke.

Filgate: You write a lot about threats from the outside world. I’m thinking particularly of “Threat Potential,” where one of Miranda’s children wanders off on vacation at an ancient ruins in Mexico, but then later on one of her kids is injured at the vacation home. Or “Bad Side In,” where Miranda wants to build a fence around her house to ward off criminals. Do you think the threats in her life are more internal than external?

Whyman: Many of the external threats Miranda obsesses over are remote possibilities and also beyond her control. But, living in DC can feel like living in a “target” city. During 9/11, the anthrax attacks, and the sniper attacks, there was a pervasive feeling of fear around town. Especially during the sniper attacks, because they were so random, that wasn’t entirely unreasonable. It went on for weeks. People were shot coming out of school, pumping gas — people were literally hiding behind their cars while they pumped gas. I remember being out on the soccer field with one of my kids, and all the parents were scared. We didn’t know if we should refuse to let it change our behavior, if we should set that example, or if we should keep the kids indoors until it all passed.

As far as internal threats, later in life, Miranda has a lot of regrets. Although she’s experienced some indisputably major life events, if she could separate herself from them, “get past them,” she’d be better off emotionally. She needs to deal with her guilt. Her powers of denial are applied to the wrong things.

Filgate: One of the themes in your book is the desire for a neat resolution — but unfortunately, that isn’t how life usually goes. At one point you write “It was resolution I wanted, the kind that was only possible in stories.” But it’s ironic you write that, since even in your stories, the resolutions are sometimes not what Miranda wants. Her decisions have consequences — whether it’s choosing the wrong guy or not getting the job she wants. What do you think would be her ideal resolution?

Whyman: As much as Miranda insists she wants resolution, her own life repeatedly demonstrates the impossibility of that goal. Nothing’s as resolving as death, right? But no one sees that as an acceptable resolution. Who are we to expect resolution? Everything keeps going. I hope that’s conveyed by the circular nature of these stories.

Filgate: I want to talk about motherhood in your book. In “Transfigured Night,” Miranda’s husband says to her: “Only selfish people don’t want children.” She’s ambivalent, in that moment, after having an abortion earlier in the book. I feel like we don’t see a ton of fictional characters who aren’t in this black or white category of yes or no to having kids. Was it difficult to write about this aspect of Miranda? Because (spoiler) she does become a mother, and one of the things I absolutely love about this book is she isn’t defined by being a mom.

Whyman: If there’s a dearth of ambivalent mothers in fiction, maybe it arises from a reluctance among parents, especially mothers, to admit they ever experienced doubt about having children, as if this will somehow make them look bad or damage their kids. To me, this is almost delusional. Show me someone who never had doubts, and I’ll show you someone who is utterly unprepared for the reality of raising kids.

If there’s a dearth of ambivalent mothers in fiction, maybe it arises from a reluctance among parents, especially mothers, to admit they ever experienced doubt about having children

Then again, I think all parents are unprepared. For some reason we apply this romanticized polarization — you do or you don’t, you want, or you don’t want to enter into this lifelong contract of deep love and deep responsibility. Shouldn’t people think about that and have at least a moment of doubt about their ability to undertake it? Shouldn’t it be okay to say you’re not sure? If fiction is going to reflect the reality, I think it needs to allow for that uncertainty. Being a parent is an awesome, amazing thing, and difficult to do well. You learn on the job. When you screw up, you’re making mistakes with humans. Talk about a daunting prospect. My kids are teenagers, and I’m still learning. Luckily, they forgive me my imperfections!

Filgate: There’s a moment in “Threat Potential” when Miranda sees her daughter fully living in the moment, and you write that the mother “remembered a time when she’d been that way, when the ordinary world seemed packed with unexpected sources of delight.” Do you think Miranda lives vicariously through her children?

Whyman: Miranda has regret and maybe even sadness about her youth. I think she sees a second chance in her daughter. In that story, her daughter is brave and exuberant and hopeful in a different way than Miranda ever was, as far as we know. Watching her daughter pierces some of Miranda’s denial and points up her regret. Miranda, like most adults, knows what it’s like to have her options closed off. Her fierce protectiveness of her daughter seems tied in with this; her daughter’s at a stage when everything is still possible for her.

Filgate: The jacket copy describes Miranda as a “hot mess,” but I don’t see her that way. I see her as a full-dimensional, real woman. Who are some of your favorite female fictional characters, and did any of them inspire you as you were working on this book?

Whyman: I’m glad you see her that way! My favorite female protagonists are Isabel Archer in Portrait of a Lady; the tragic figure Lily Bart in The House of Mirth; Dorothea Brooke in Middlemarch; the young (I think unnamed) narrator in Alice McDermott’s That Night; Claudia Hampton in Moon Tiger — I could go on, but probably you see the pattern. I think Miranda owes a lot to Isabel Archer, whose lack of experience and impetuousness lead to bad decisions to which she stubbornly adheres. That’s an oversimplification, but there are commonalities. None of it’s intentional, just that these are stories I’ve read many times, and they’ve seeped into my unconscious. This is the kind of character I’m drawn to, so it makes sense that I would attempt to create a female protagonist somewhat in that image.

Filgate: Are you done with Miranda, or could you see yourself writing another book about her?

Whyman: Hard to say. After all, years ago, I thought I was done with her after writing one story! I’m devoted to a novel right now, a very different story. I won’t say never, though. Never say never… Meanwhile, there is one more Miranda story out there, published in McSweeney’s Quarterly #48. It takes place ten years after the end of the book. We had good reasons for not including it in the collection, but it’s one way I was thinking about going, regarding her future. In fact, it’s being recorded by Audible for an audio anthology of McSweeney’s stories.

Filgate: I love that Blake Bailey describes you as “a somewhat more erotic Lorrie Moore.” I think that’s the perfect description. Let’s talk about writing about sex. How difficult is it? What are the challenges?

Whyman: I’d like that quote on a T-shirt. I admit I don’t find it too difficult to write a sexy scene. To me, it seems tougher to move someone across a room than across a sofa. I automatically use humor in sex scenes, because to me, those situations are often naturally funny; that’s just how I think.

I admit I don’t find it too difficult to write a sexy scene. To me, it seems tougher to move someone across a room than across a sofa.

I ask myself the same questions I’d ask about anything a character is doing in a story: Is this how she would behave in this particular situation? Also: What’s important here? What does the reader need to see and understand? Less is more. Sometimes I think when writers approach a sex scene, there’s a tendency to become hyperaware and wake oneself out of the dream state that’s necessary to write. Instead, you’re going, Sex Scene Alert!! Be eloquent! Get serious! Describe body parts! Tab A into Slot B, here we go! I think we need to relax a little.

Filgate: In an interview with Largehearted Boy, you talked about dealing with a sudden hearing loss in one ear. Your hearing is now back to normal, but during that difficult time you realized music is crucial to your writing process — even though you don’t listen while writing. Why is music so important to you, and how has it influenced your work?

Whyman: That problem was a complete surprise to me. I was unable to write for three months, until my hearing returned to normal. Music not only sounded wrong, but it was painful at times. The high pitches were like an attack on my eardrums.

When I’m not writing, when I’m running, for instance, I’m often listening to music. My mind wanders, and I write in my head. The trance state induced by music encourages my process, the daydreaming that’s required for writing fiction. Radiohead is great for that… But so is anything, while I’m running. The steady motion of running paired with the rhythm of the music, heartbeat, breathing — it all comes together to get me into the right frame for letting my imagination go. I can run for blocks and not recall anything about how I got from point A to point B. Probably I should stay out of traffic at times like that…

Filgate: I saw on your website that a music theater piece of “Transfigured Night” is in development with the composer Scott Wheeler. Tell us about that!

Whyman: Scott’s a MacDowell Colony and Yaddo alum — we know each other through MacDowell. He read my stories and came to me about doing this project. I feel incredibly privileged to be working with him. He recently finished a song cycle in collaboration with the poet Paul Muldoon; it premiered in New York in May. Scott told me the only other fiction writer he ever collaborated with was William Maxwell.

The story “Transfigured Night” is set during the early days of Miranda’s marriage. A large part of it takes place at the symphony. The title is a music piece, a symphony by Schoenberg, which is thematically resonant. I’m adapting the text, which will be spoken, not sung, and Scott is writing the music. The music piece will be more dreamlike, less straight realism, than the original story. That’s often what happens when you tell part of a story through music. But also, there’s a dreamlike aspect to the original story that we’d like to develop.

We met recently with our director and playwright friend Austin Pendleton, who advised us on possible theaters to workshop the piece and suggested a couple of actors for the role of Miranda. I’m curious to know which actors readers might imagine as Miranda!

Filgate: Where do your story ideas come from? And what is your writing process like?

Whyman: I might begin with a sentence that occurs to me based on something I overheard (I encourage writers to eavesdrop!) or witnessed, or a tiny aspect of something I experienced, though just as often, it’s more like free-association. A phrase will pop into my head devoid of any origin that I can identify. By the time I’m done writing a story, often I can’t even identify what the original impulse was. So much of this process is unconscious. I start with a phrase — I ask who’s saying this, or who is this about? In the case of these stories, because I was writing stories that followed Miranda through time, I started with a kernel like that, but then I had an intention, like, let’s see what happens when Miranda hangs out with a guy she can only be friends with…

I used to think I had frequent bouts of writer’s block, but it turned out it was an actual stage in my work. I write like mad on a draft, reach the middle-ish part, and stall in a big way, no idea where to go next. I stop and flail around for days…or weeks… I get very grouchy during that time, feel like I’ll never get going again. And then — if I were a cartoon, you’d see a light bulb pop up above my head. Oh yeah, of course, that’s what happens. Once I make it through that stall-out, it’s as if it never occurred.

I need the just-right ending, too; those closing lines are crucial. Some stories fizzle out, and I’m strict with myself about that. When I stop trying too hard to think about a specific problem in a story, that’s usually when the solution comes. I’ve had to accept that uncertainty is in fact a good thing, that flailing is part of my process.

About Paula Whyman and Michele Filgate

Paula Whyman’s writing has appeared in McSweeney’s Quarterly, Ploughshares, Virginia Quarterly Review, The Washington Post, The Rumpus, and on NPR’s All Things Considered. She is a member of The MacDowell Colony Fellows Executive Committee. A music theater piece, “Transfigured Night,” based on a story in this collection, is in development with composer Scott Wheeler. A native of Washington, DC, she now lives in Maryland.

Michele Filgate is a contributing editor at Literary Hub and VP/Awards for the National Book Critics Circle. She teaches creative nonfiction for The Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop and Catapult and curates a quarterly series on women writers called Red Ink. Brooklyn Magazine recently selected her as one of the “100 Most Influential People in Brooklyn Culture.”