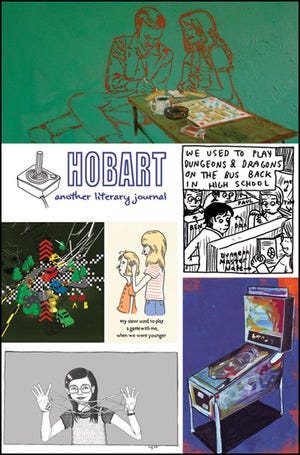

Lit Mags

Pearl

by Mary Miller, recommended by Hobart

EDITOR’S NOTE by Elizabeth Ellen

I can no longer remember which of Mary Miller’s stories I read first. I can’t remember when I first knew the name “Mary Miller.” Or whose “private room” we were both in in Zoetrope’s online workshop. I can’t even remember when we first met. (Which makes me think of those Kanye lines, “Hey, do you remember where we first met? Okay, I don’t remember where we first met. But, hey, admitting is the first step.”) Maybe all of those “firsts” are unimportant. (The point is, I know Mary Miller. I know her stories. Kim and Kanye are getting married. Mary likes to call me her “Boston wife.” We (SF/LD Books) published Mary’s collection, Big World, in 2009; have already had to reprint it twice since then.)

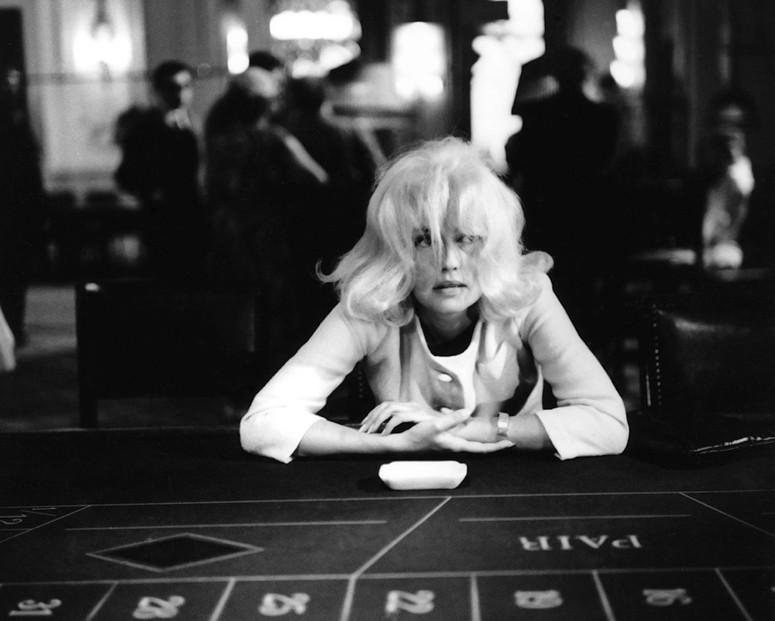

“Pearl” was definitely one of the firsts. We published it in issue #9 of Hobart, our “Games” issue. I think Aaron picked it because half of it takes place in a casino and there’s gambling. But also because it’s hella tight and droll and is in general “classic Mary Miller.” (There is sex and a line about having your period and wearing white pants, and more sex, and fingers in mouths, and a lot of LOL lines, like, “I’d been trying out the truth lately and people didn’t like it.” Okay, maybe that’s not laugh-out-loud, maybe it’s more… smile-and-nod-to-yourself, knowingly.)

A little while back, Kyle Minor wrote up a post on HTML GIANT about the openings of Mary’s stories; she’s known for her openings. And “Pearl” is one of her best:

“At the breakfast table my mother said the world was my oyster.

‘While I’m still young and pretty,’ I told her.”

The opening of the story reminds me a little of Mary Gaitskill’s “Secretary,” possibly because it’s set in an office and there is mention of pantyhose and short skirts and high heels and (the aforementioned) fingers in mouths. (Gaitskill is someone I think we both, Mary and I, have been compared to, a comparison I think we both “will take.”) But “Pearl” is set fully in Mary Miller’s world, where you have sex with a bartender in a casino while waiting on the man you came with to retrieve you, and while having sex with the bartender, you wield from planning out a long-term relationship with him in which you watch his dog while he’s in Iraq writing you letters, to extricating yourself from him prematurely in this casino hallway because you, “felt like fucking everything up because it was so easy to fuck up and he wouldn’t be able to do a damn thing about it…”

“Pearl” is full of sentences like that you want to underline. Or yell. Or write in magic marker on your wall. “…and he wouldn’t be able to do a damn thing about it.” Hell yeah. Hella tight.

Elizabeth Ellen

Editor, Hobart

Pearl

Mary Miller

Share article

At the breakfast table my mother said the world was my oyster.

“While I’m still young and pretty,” I said.

My father didn’t think the world was my oyster. I could tell by his silence he thought I should ask my husband to come back.

I’d had to move back home. Once there, things took up where they left off. My parents wanted to know where I was going. They felt obligated to tell me where they were going. I didn’t care where they were going, though I liked to know when they were gone.

My friend’s father called and said they were looking for a receptionist at his law firm so I went and answered the telephones. I liked to think it was temporary. I wore short skirts and high heels and pantyhose. Pantyhose were expensive. They snagged and ripped but I couldn’t bring myself to throw them out. They used to come in eggs but now it was envelopes.

At work, I put my nails in my mouth and bit down. They were healthy and strong and the tips white like a French manicure.

One of the partners would come and sit on my desk, take my hands out of my mouth. He had a thick head of hair and the whites of his eyes were laced with bright red like they’d been shattered. His wife was an alcoholic, he told me, his daughter depressed, manic, depressed. They took turns unraveling and getting well and all of his money was tied up in property and retirement and he was cash poor and his father was dead and his mother was dead and his brother was dead. I let him talk and talk, didn’t let on that he could bend me over right there, that I didn’t need to hear his sob story. He had no idea how small my world had become.

His name was Robert but everyone called him Bob. I called him Robert. I had a problem calling anyone Bob. I didn’t like palindromes. It was too abrupt: “Bob, cob, lob, rob, sob,” I said, by way of explanation.

My birthday was coming up. It was as good excuse as any.

I met him in a restaurant inside a giant mirrored ball on the twenty-fifth floor. The ball was on top of a hotel on top of a casino. I was worried. My pants were white, my period set to start. I’d left my parents in front of the television. Every penny I spent was mine.

After dinner, we were going to gamble, he said, and I’d be his lucky charm. This also worried me. Gambling required a delicate balance of desperation and delusion, and I wasn’t feeling much like deluding myself.

“I don’t know how lucky I feel,” I said.

“You’re not the one who’s got to feel it,” he said, leaning forward.

I shifted in my chair, refolded the napkin on my lap. In liquor stores, I still got that sinking feeling left over from high school: hair too flat and nose all wrong, the license expired. He ordered a bottle of champagne.

The waitress left us alone for a long while, a father and his daughter out for a graduation celebration — the presentation of a fat check, or the keys to a BMW. When she returned, Robert ordered an eight-ounce filet and a baked potato. I surprised myself by asking for the same. I didn’t eat steak. I ate chicken, tofu. I drank soymilk.

He asked me about books, what kinds of books I liked. He’d seen me reading in the break room at lunch. I could see it had just occurred to him that he might ask me a question.

“I like books about fucked-up people,” I said. “The kind you have to tear the cover off because there’s a girl on the toilet staring at her shadow.”

Our salads came. I ate but I wasn’t hungry. I hadn’t been hungry since my husband left. I thought about my mother’s sister, the one named after a dessert, and how she was still praying for my husband to impregnate me. She prayed to St. Jude, she told me, the patron saint of lost and hopeless causes, and I didn’t mind being lost but hopeless bothered me. Hopeless was going too far. Someone was going to have to tell her.

We ate in silence, then rode the elevator down and made our way, weaving in and out, to the tables. Blackjack was his game. I kept a hand on him because it was crowded and I was in the way, so people could see that I belonged. A part of me wanted him to win and a part of me wanted him to lose and a part of me wondered what my husband had eaten and whether he’d taken a shit and how many cigarettes he’d smoked.

We went to the bar in the middle of the casino, water coming down the walls.

“We should stay the night,” he said. He still had chips in his pocket. I could hear him rattling them around.

“I’d have to call my mother.”

“You’re a big girl now.”

“I keep forgetting,” I said.

“So I’ll get a room and we’ll stay. Two beds? One? Your call. If you’re not comfortable — ”

“I don’t feel like calling,” I said.

His shoulders sank. I went to take his hand but he stood and brushed the front of his pants like there were crumbs all over him. “Stay right there.”

“I’m not going anywhere.”

“Don’t move.” And then he was gone but he was coming back. I thought maybe I’d move down a seat. The bartenders were young and female, fake breasts and blonde hair: one pretty, one plain. But maybe the plain one only needed more makeup, or maybe she would have been pretty on her own, without the comparison. It was hard to say. I felt sorry for her. It was her face.

Robert came back with two keys. He handed me one, took out his wallet and opened it. Worn brown leather, soft.

“Here,” he said. “Go play. Have fun.”

I put the bill in the machine, which gave me smaller bills, and then I went and sat at a different bar and slipped a twenty into a video poker machine. The bartender looked military. He fixed my drink, put his elbow on the bar. He watched me but he didn’t comment. I was sure they weren’t supposed to comment.

“You’re making me nervous,” I said.

“Is this all it takes?”

“Less.”

I looked up and he started talking. He was in the Guard. I didn’t know anything about the Guard except that once I asked my father about Vietnam and he said the people who joined it were the lowest of the low. He’d be gone soon, he told me. He had no one to leave and no one to come back to and he used to be sort of fat with a ponytail but now he didn’t have any fat on him and he was practically bald and it was strange living in a body he didn’t recognize.

“That’s interesting,” I said.

“I know, I know,” he said. “You don’t want to hear my story.” He ran a hand over his head. I imagined he could still feel the hair between his fingers.

“Tonight I’d like to talk to someone who doesn’t have a story. Someone who loves their mama and their dog.”

“I love my dog,” he said.

“What kind?”

“Yellow lab.”

“That figures,” I said. “Hey. What should I do here?”

“Just the Ace. Dog’s sweet, fixed. Loves to walk. You can keep him for me while I’m gone.”

“I can’t keep your dog,” I said. “What the hell’s wrong with you?”

He went to the other side of the bar to serve an older couple and then he came back and told me his name was David.

“Jillian,” I said.

“I was kidding about you keeping my dog. My ex-girlfriend’s going to keep her. She’s a great person.”

I nodded and he said that actually she was a total bitch but she liked animals. I smiled. He showed me his back and I stopped playing and waited for him to look at me and then he did and I didn’t look away like I usually do because there wasn’t any time for it.

I pointed at my drink and he fixed me another.

“Are you taking a break anytime soon?” I asked, and then I was following him down a brightly lit hallway and I could see my drink sitting there, sweating, wondering when I’d be back. The walls were white and blank and the hallway so long I couldn’t see the end of it and all I could think to say was that the tunnel was like death but I didn’t say that because already I could hear it hanging in the air above us and then he stopped and took a key from his pocket.

There were boxes everywhere. I pulled his shirt out of his pants and ran my hand over his stomach, which was flat and brown like the boxes, and he lifted his arms and leaned forward so I could pull it off and then he was kissing my neck, my mouth, my cheeks, my eyelids, which was sad and unexpected and made me think he thought he wasn’t coming back. He wanted me to keep his dog and I thought maybe I should instead of letting his ex-girlfriend have him because already I had taken a strong dislike to this ex-girlfriend.

He unbuttoned my pants and spun me around and I waited for him to put a condom on while I thought about my number, skyrocketing, two men in one day. I wouldn’t have enough hands to count. I wanted a cigarette. He felt between my legs and said how wet I was and opened me up and stuck himself inside me and this went on for some time, I don’t remember how long it went on but I was there among the boxes and the white light and he was going to Iraq where he would need someone to write a letter to and I wanted to be the recipient of his letters and it made me think of Harry Potter and all those letters pouring in, you couldn’t stop them, no matter what you did you couldn’t stop them. I wanted his letters and I wanted to walk his dog every morning and I’d lose fifteen pounds while he was away and then he’d come home and think I was the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen, or else he wouldn’t come home and I’d still be thin and I’d still have his dog. Either way.

“My boyfriend’s probably looking for me,” I said, because it seemed like he was having a hard time so I thought I’d help him out even though I was close, maybe just another minute, but I felt like fucking everything up because it was so easy to fuck up and he wouldn’t be able to do a damn thing about it and I didn’t really want his dog or his letters. I didn’t really want his love.

I took the bed by the window and turned on the television. I wasn’t too drunk. I set my phone on the table and waited for it to ring.

It was my mother. I told her I was spending the night out. She wanted to know where and I said it was none of her concern, which made it her concern, so I told her I’d had too much to drink and was staying at Polly’s because I wasn’t divorced yet and my mother didn’t understand technicalities. My husband wasn’t coming back, and I wasn’t going to ask him to come back even if it made me complicit in his leaving.

Robert came in late, stumbling, his shirt untucked. He stripped down to his underwear, and fell into the other bed facing me. He folded his hands under his cheek like a child and I could see his shattered eyes and his nose, crooked and bulb-tipped, and I knew he was just like the rest of them.

“I’m not going to touch you,” he said.

“How come?”

“You remind me of someone.”

“Your daughter?”

“I thought I’d do better by her,” he said.

The air conditioner clicked on. I wondered if my mother believed I was staying at Polly’s. I knew she didn’t, but then tomorrow, when I told her where I’d really been, she’d act genuinely surprised.

I’d been trying out the truth lately and people didn’t like it. I wasn’t sure how I felt about it yet. It made messes of things that didn’t require a mess.

“I’m sure you did what you could,” I said.

“As soon as she was born, I was done with her.”

“You were probably just afraid.”

“That wasn’t it,” he said.

“We’re all afraid, but see, men, they get violent when they’re afraid.”

“I’m not a violent person.”

“That’s why you have to go and fuck yourself up,” I said.

He didn’t say anything and then he said maybe I was right and I wanted to say something to make him feel better but I couldn’t think of anything. I listened to him breathe. I pictured myself waking up in a few hours and sitting on his bed: my finger beneath his nose, ear to his chest, checking.

“I’m forty-eight,” he said.

“That’s not too old.”

“I’ll be forty-nine next month.”

“You could live another thirty years, easy.”

“Not in this body.”

“Your body’s fine. I like your body.”

“If I fucked you, I’d only be fucking her,” he said, and he turned to the wall, his back fluffy with hair.

“I’m not her,” I said.

“You’re all her.”

I got up and went to the bathroom and washed my face, my hands, everything already clean. The soap had flecks of oatmeal in it, like tiny bits of paper and insect wings. I filled a coffee mug with water and drank it and then I stood still and listened.

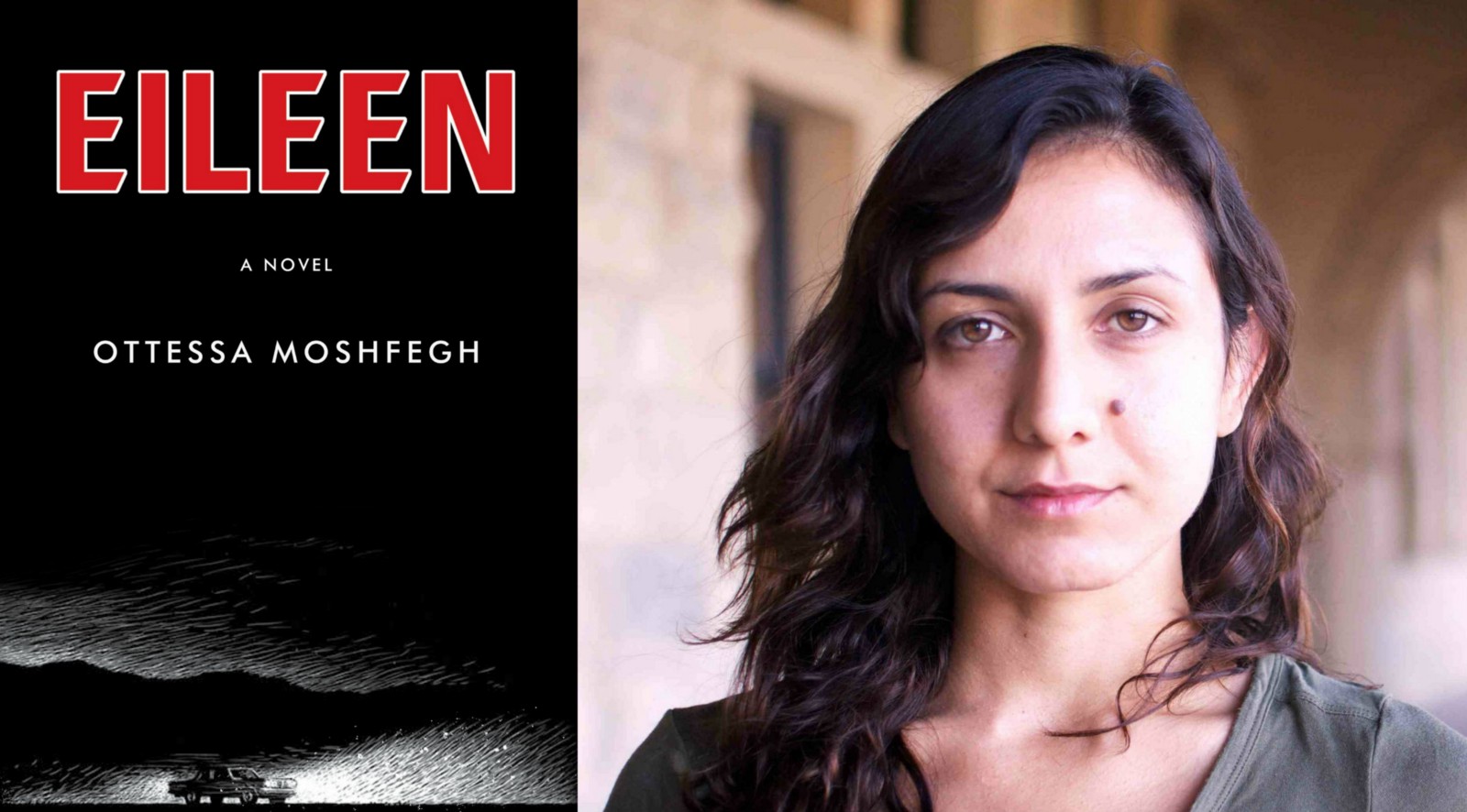

About the Author

Mary Miller is the author of Big World and The Last Days of California.

About the Guest Editor

Hobart Publishing consists of the “biannual”/irregular print journal, Hobart: another literary journal; the daily Hobart Web; and the books division, Short Flight/Long Drive Books, all based in Ann Arbor, MI (and also, really, just “on the Internet”). The print arm is edited by Aaron Burch and Elizabeth Ellen and the last year or so has been especially exciting and, frankly, shocking, with regard to anthology inclusions, general recognitions, etc. Stories and essays from the last couple of issues have been reprinted in Best American Short Stories, Best American Essays, O. Henry Prize Stories, and New Stories From the Midwest. Lots more info/stories/content at www.hobartpulp.com.

“Pearl” originally appeared in Hobart and is reprinted here by permission of the author. © Copyright 2013 Mary Miller. All rights reserved by the author.