essays

People Keep Putting Hidden Anti-Trump Messages in Their Resignation Letters—Here’s Why

The acrostic is the perfect poetic form for this political moment

O n Wednesday August 17th, all 17 members of the President’s Committee on The Arts and The Humanities resigned their posts, citing President Trump’s equivocation regarding white supremacist demonstrations in Charlottesville, Virginia. The resigning members stated in a co-written letter that “speaking truth to power is never easy, ” but that “supremacy, discrimination, and vitriol are not American values.” Embedded in the statement, addressed directly to the commander in chief, was the word “RESIST,” spelled using the first letter of each paragraph.

While it’s no surprise that a committee convened to advise the president on cultural issues would resort to a somewhat obscure literary form to hammer home their disgust, the humanities committee wasn’t alone in coding its resignation letter for maximum impact. Daniel Kammen, one of seven science envoys working in the State Department, resigned his post August 23rd with a letter that used the same method to spell out the word “IMPEACH.”

Neither letter is shy about criticizing the current administration’s choices to gut arts funding, back out of measures to reduce the effects of climate change, or endorse the actions of white supremacists, so why bother hiding these messages to “RESIST” or “IMPEACH” in the first place? The President has a reputation for barely reading what he signs into law, which likely disqualifies him from enthusiasm about close-reading anything, let alone reading as a mode of confronting his own vocal critics. Perhaps the committee members and Kammen are aping Trump’s own declarative style, subbing in their own one-word pronouncements in summation of their experiences the same way the president uses “Sad!” as punctuation for his ubiquitous Twitter tirades. Regardless of their inspiration, the acrostics in these letters act as powerful distillations of their overall content, acting as a call to arms for anyone who finds themselves frustrated with the man in charge of the country’s future.

The acrostics in these letters act as powerful distillations of their overall content, acting as a call to arms.

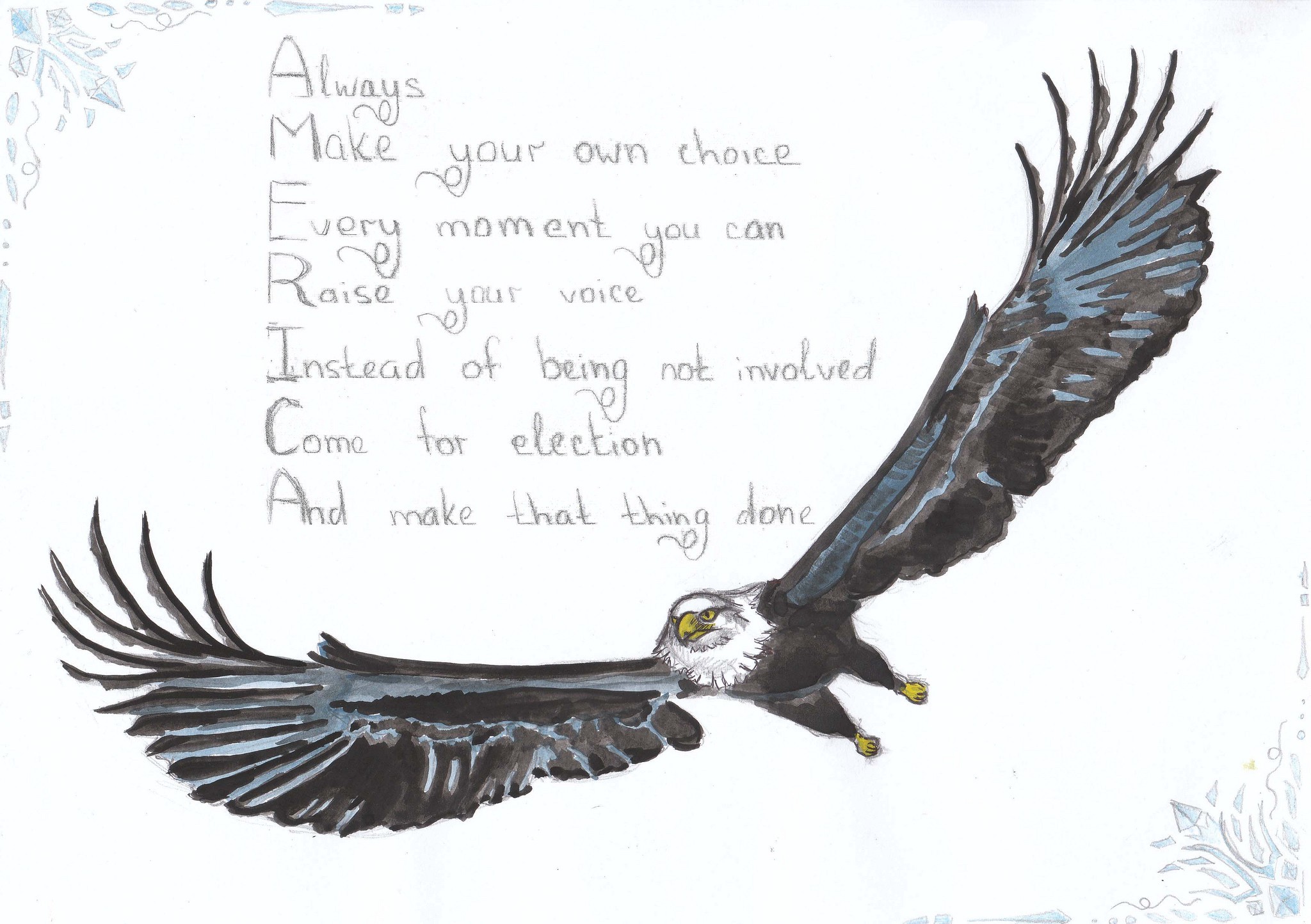

Acrostic poems are a form of constrained writing as old as the Bible, appearing especially frequently in the Psalms and the Book of Lamentations. The Roman poet Publilius Optatianus Porphyrius wrote to Emperor Constantine in acrostic to beg to return from exile. In medieval times, acrostics would often spell out the name of an author’s patron. The Dutch national anthem “Het Wilhelmus” contains the name of William of Orange, also the subject of the poem. Acrostics as a literary form have great steganographic potential, since the hidden word being spelled out is only apparent to an observant reader seeking a secondary message in addition to the one readily apparent on the page.

Enterprising writing instructors sometimes use acrostics to demonstrate how poems can explicitly embody their subjects, arranging the components to literally spell out what might otherwise be merely implied. Lewis Carroll’s acrostic poem at the end of Through The Looking-Glass spells out the name of its muse, the real-life Alice. William Blake uses acrostic in the third stanza of his poem “London” to spell out “HEAR,” asking his reader to come as close to the sounds of the city as someone experiencing them in real time. The Academy of American Poets describes the form as a kind of poem that seeks “to reveal while attempting to conceal.” Acrostics overlap the concrete and conceptual, unifying them.

Recently it feels as though the concrete and conceptual have indeed collapsed into one another. Statues of confederate generals are no longer outdated monuments to disgraced secessionists but rallying points for those who wish to maintain political power as the exclusive domain of white men. What better time for the return of the acrostic to common use than this moment, when we hear constant exhortations from both sides of the aisle demanding we show the world what it is America truly stands for? Choosing the most effective way to condemn the president isn’t something his detractors can afford to be subtle about. Though the acrostic is a kind of coded language, in the letters it serves to underscore their message of refusal to remain complicit in the failures of the current administration.

In following the acrostic’s appearances in recent news, I see the requests I make of my own students: Stick to what’s essential to the story. Sharpen your language. Exploit the connotations of the words you tell your story with. Use the most active verbs available. I can’t help but see these resignation letters as an attempt to teach us the same thing. The verbs are strong, the grievances and motivations listed as plainly and powerfully as possible. “We know the importance of open and free dialogue,” the PCAH letter offers, later landing the same paragraph on, “Your words and actions push us all further away from the freedoms we are guaranteed.” To borrow some strong language from my boyfriend when we read the letter out loud at breakfast last week: “Fucking Jhumpa Lahiri coming in with a fastball.” There is no better example of sharpness or careful choice than being able to distill an entire letter to a single, unequivocal word.

Declaring dissent in public means making oneself vulnerable to being labeled reactionary. These letters predict and negate that accusation.

Declaring dissent in public means making oneself vulnerable to being labeled reactionary. These letters predict and negate that accusation. The presence of an acrostic is proof of how carefully crafted these statements are. It’s next to impossible that either letter stumbled into spelling out a refrain that sprang up in direct response to Trump’s election or the word for how our democracy might lawfully remove him from office.

Poems have always been political because of their ability to elevate a momentary experience or observation to immortality. They are flexible creatures that contain infinite space for examining whatever they choose to concern themselves with. A poem has as many layers as the poet imposes on it. Acrostics task a poet with explicating a single word in such a way that that word acts as a vessel for the worlds beyond it. The form exists as a tool for slowing down the meaning of a single word, then exploding its possibilities.

One example I came across in researching the history of political acrostics feels particularly aligned with the past week’s examples of the form. In 1949, when Newfoundland became a part of Canada, The Newfoundland Evening Telegram published a seemingly affectionate poem on the occasion of the departure of their British governor, Gordon Macdonald. But beneath the poem’s request that Macdonald “remember if you will the kindness and the love/Devotion and the respect that we the people have for Thee,” lay an acrostic that spelled out “THE BASTARD.” Bureaucracy often demands language with a certain level of decorum, but the acrostic made space for the farewell the people of Newfoundland would rather have offered, had they not been restrained by propriety. Calls to resist and impeach engage in the same bureaucratic decorousness, couching their extreme acrostic summations in the more restrained writing of the body of the text. The letters use the acrostic to turn that decorousness on its ear, making it impossible for anyone to mistake their message simply because they aren’t shouting it into a megaphone or carrying it on a sign at a protest.

Elucidating where you stand in relation to Trump, with his shall we say singularly lyric way of regurgitating his own rhetoric, is probably a poetic form unto itself at this point. The resignation letters engage in his game of coded buzzwords, reinforcing and re-contextualizing their own content via their employment of the acrostic. Carefully chosen language communicates on many levels simultaneously, and in these two instances it does so to great effect. Greater still is the contrast between the care for language the committee and Kammen show and the current administration’s extreme difficulty maintaining a consistent press secretary, a consistent stance on important issues, a consistency at anything besides inconsistency.

The letters’ care for language contrasts with the current administration’s extreme difficulty maintaining a consistency at anything besides inconsistency.

The current White House seems to throw out imprecise language on purpose so that it may revise on a constant basis, never committing its statements to a final draft. These revisions are often impromptu, inspired both by rhetorical circumstance and the audience of the moment. Extreme intentionality is antithetical to the Trump administration, making the acrostic form an especially powerful critical tool for those opposed to the president and his supporters.

Yoked with the responsibility of taking a strong stance against the dismantling of the arts and sciences as American institutions, people are turning to poetic forms as the best mode of denouncing Trump. It’s one thing to walk away from association with Trump and all his fumbling with a strong statement of disavowal, and I quite admire that action regardless of how it’s expressed. But to see poetry weaponized, so to speak, by those who are truly paying attention to how much of our democracy is unraveling is truly special. Trump seems to be counting on the public not noticing what he’s accomplishing behind a curtain of performative incompetence. Maybe it’s best we spell it out for him: he’s underestimating the arts as a tool for change.