Craft

Planes Flying over a Monster: The Writing Life in Mexico City

Daniel Saldaña París on the capital’s poets, cartels & piano tuners

We’ve asked our favorite international authors to write about literary communities and cultures around the globe. Their essays make up Electric Literature’s The Writing Life Around the World series. This month’s installment is by the Mexican writer, Daniel Saldaña París. His novel, Among Strange Victims, was recently released in the U.S. by Coffee House Press.

I get so close to the airplane window that my face is almost touching it. We’re flying over the city. I play at identifying the buildings: the World Trade Center, formerly known as the Hotel de México; the Torre Latinoamericana in the distance, marking the border of the Centro Histórico; the Reforma 222 shopping mall, which a few years ago, before I emigrated to Canada, I would pass every day on my way to my job as an editor.

I haven’t been in Mexico City for twelve months, and all I can think is that it’s horrible, and I love it. This contradiction is perfectly common; all of us chilangos have felt it at one time or another when spotting the monster from afar. I think of all the times I’ve seen the infinite ocean — of city streets, gray houses and dirty avenues — spread itself at my feet as I sat on a plane. Every time I’ve landed in Mexico, I’ve felt this same mixture of repulsion and enchantment, this movement of attraction and rejection.

This dual impulse was felt, too, by Efraín Huerta, who in 1944 published his “Declaración de amor” (“Declaration of Love,” namely to Mexico City) in a book that also contained one of the most beautiful and dead-on texts ever written about Mexico City, “Declaración de odio” (“Declaration of Hatred”). I sometimes read the second poem aloud, exulted, as a way of recalling my roots: “We declare our hatred for you perfected by the force / of feeling you more immense each day, / more bland every hour, more violent every line.”

Ten years ago exactly I landed at Mexico City’s Benito Juárez International, the airport we’re approaching now. I was returning from Madrid after four years in Spain. I was a young poet, aged 21, and had a grant from the Mexican government to write my first book. I had never lived in the city as an adult, but a fireproof arrogance — characteristic of young poets — made me trust blindly in the future.

It was October 2006, and I settled into a small apartment in the Colonia Roma district, which back then wasn’t so ridiculously gentrified.

To enter my block, a precinct of plants and caged parakeets, you had to pass between a synagogue and a piano repair shop. The soundtrack of my life during those years was a strange mix of Jewish music and atonal experiments, like a John Zorn composition arising spontaneously from the streets. An odd architectural whim had left the short hallway between my living room, bedroom and kitchen open to the sky — roofless — and so when it rained I got wet just moving from one room to another.

I had very few belongings: an orchid taken from my mother’s house, a handful of poetry books and a cafetera italiana — a moka pot. I lived on quesadillas, sex and canned beer. I’d sit in a little wooden chair in my roofless hallway, facing my orchid, and write poems on an old laptop. I knew no one; no one knew me. The Distrito Federal (which in the meantime is no longer called the Distrito Federal) was a cluster of possibilities.

Before long I got to know some other poets through the grant I had. I danced with them and fought with them, I loved them, I got drunk with them, we traded insults. The things that young poets in any city do — and that, paradoxically, make them feel unique. I felt unique listening to the piano tuner’s imperfect notes as I danced in the roofless hallway of my little apartment, in my indoor rain.

I’ve spent two weeks in Mexico City since that landing at Benito Juárez International — since the moment when I thought, like Efraín Huerta, that I love and hate this city. Two weeks of going out every day, of coming back at dawn, drunk on electric light and intensity, smog and tequila. Two weeks in the strange parenthesis that is this visit to my birthplace after a year living abroad.

Jorge, Benjamín and I are lying on the roof terrace, watching the sky and talking. Every once in a while the noise of an airplane interrupts our conversation. The district we’re in, Colonia Narvarte, lies under the traffic pattern of Benito Juárez Airport. With increasing frequency after two in the afternoon, hundreds of commercial flights describe an elegant curve over Benjamín’s house before taking aim at one of the ancient airport’s two runways. (It has always amazed me that the names of those runways should be 5L/23R and 5R/23L, as if we weren’t capable of recognizing that there are precisely two of them, and therefore they might as well be called One and Two.)

Three hours ago, Benjamín, Jorge and I each dropped half a dose of LSD. Now, immersed in the hallucinatory lucidity of the drug, we’re conversing with a certain lethargy, interrupted from time to time by the noise of the turbines above us. It’s a Sunday, resplendent and slow. It must be three or four in the afternoon.

Every time the sound of turbines cuts the sky in half, Benjamín, Jorge and I fall silent and watch and listen with all the power of our attention. The plane pokes its nose into our field of vision from the far left, which I imagine corresponds to north, and from there it glides smoothly to the far right, like a hot knife through a block of butter. For a few seconds after the plane is no longer visible from where we lie, its noise echoes. The LSD intensifies the Doppler effect, and I know all three of us — Benjamín, Jorge and I — are thinking of just that: how the sound of an airplane reveals, in an almost scientific way, the curvature of the planet and the exact size of the atmosphere above us.

A little more than a year ago, just before emigrating to Canada, I somewhat unexpectedly took on the leading role in a movie being filmed in Mexico City. I say it was unexpected because I’m not an actor, and I had never worked in the film industry before. But I agreed to act in the movie because I thought it might be an interesting experience — and because I needed the money. Of the two months the business lasted in total, four days’ shooting took place in Colonia Narvarte some ten streets from Benjamín’s house, where I’m lying on the roof terrace and watching the sky. The planes passing overhead during filming were a torture for the sound engineer, who each time lost important moments of a dialogue that was more or less improvised and unrepeatable. Knowing the problems this would create for the editing process, I got into the habit of shutting up whenever an airplane went by. As soon as I’d sense the hoarse sound of turbines in the distance, I’d pause, more or less naturally, and not resume the dialogue until the noise had died away. The upshot was that the director ended up filming takes of up to seventeen minutes without a cut — to the great irritation of most of the crew, who were accustomed to working in a more conservative and expeditious style. This experience made me extremely sensitive to the planes over Mexico City, planes I had been ignoring with relative success for thirty years. Ever since then I’ve been unable to hold a conversation in Mexico City without pausing, however briefly, at the sound of an approaching plane.

I don’t know where I got the cockeyed notion that I might write for a living, but it’s an impractical one to say the least. Nobody writes for a living in Mexico. Or rather some people do, but those are people I don’t know and ultimately have no interest at all in knowing. To live comfortably as a writer in Mexico, you need to have a lot of opinions about soccer and politics — in a very shallow sense of the word politics, you can be sure. The rest of us Mexican writers spend our time sending pitiful e-mails soliciting work or applying for grants, when we’re not laboring obscene hours at jobs somehow related to writing.

I didn’t know any of this when I came to live in the city exactly ten years ago, eager to express in innocent verses my squalid vision of the world while listening to the music of the synagogue and the piano tuner. Back then I believed, with ridiculous fervor, that I would be the glorious exception to the norm. I’d devote myself to writing, and from my roofless hallway in Colonia Roma, I’d gradually conquer the world. Instead I ended up working ten- and eleven-hour days for a magazine, a publishing house, a festival, an independent movie.

Writing in Mexico City is like holding a conversation when you’re under the takeoff and landing path of the city’s airplanes: you have to shut up sometimes, to let the noise take over everything, to let the sky split in two before picking up where you left off. From 2006 to 2015 I tried to be a writer in Mexico City. The sky split in two many, many times during those years.

At first I survived on grants. Now, in Mexico there are grants for young writers which require them to attend workshops led by their senior colleagues. These older writers are, barring some exceptions, people whose only merit is having gotten old. Literature in Mexico is a gerontocracy. The old are praised for surviving to another birthday; the young are regarded with suspicion and treated with contempt. And the workshops, in general, are places where all the edges are filed off a piece of writing, where a text is homogenized until it loses all capacity to wound or bewilder. For three years I lived off grants of this kind, confronting the workshop system with hyperbolic obstinacy.

Literature in Mexico is a gerontocracy. The old are praised for surviving to another birthday; the young are regarded with suspicion and treated with contempt.

But all grants must come to an end — it’s a law of physics. When I started working as an editor at a literary magazine, I thought that it wasn’t such a bad thing to be doing, all things considered. I could write a little during the slowest week, right after an issue had been put to bed. I could request a piece from any writer who interested me. Imagine, they were paying me to read poetry — not a bad gig overall. But this illusion was short-lived: the magazine was (and still is) a nest of vipers. Editing each issue was like dancing with hyenas. Writers close to political power dividing up an imaginary prestige and macerating in the mediocrity of a prose that aspired at best to pallid efficiency. They weren’t all like that, but most were. The editor-in-chief, a well-known liberal, turned against me because I had dared to address him as “tú” rather than “usted” — my damned Montessori education. So finally I left.

Those years weren’t all bad, though. I married a beautiful, intelligent woman, and we moved together to Colonia Narvarte, directly under the landing path of the airplanes. The recurrent sound of turbines became the new soundtrack of my existence, replacing the music of the synagogue and the piano tuner.

Little by little everything got twisted, my vice and my violence stoked by the hypertrophic city. I observed the growth of my alcoholism with tenderness, as others watch the maturation of a child. I became irritable, prone to excesses of wrath. I wrote a novel in the dead hours of my devastation. And then the sky split in two. I got divorced. I lost all faith in what I was doing. I had to stay silent for a time, listening to the passing airplanes.

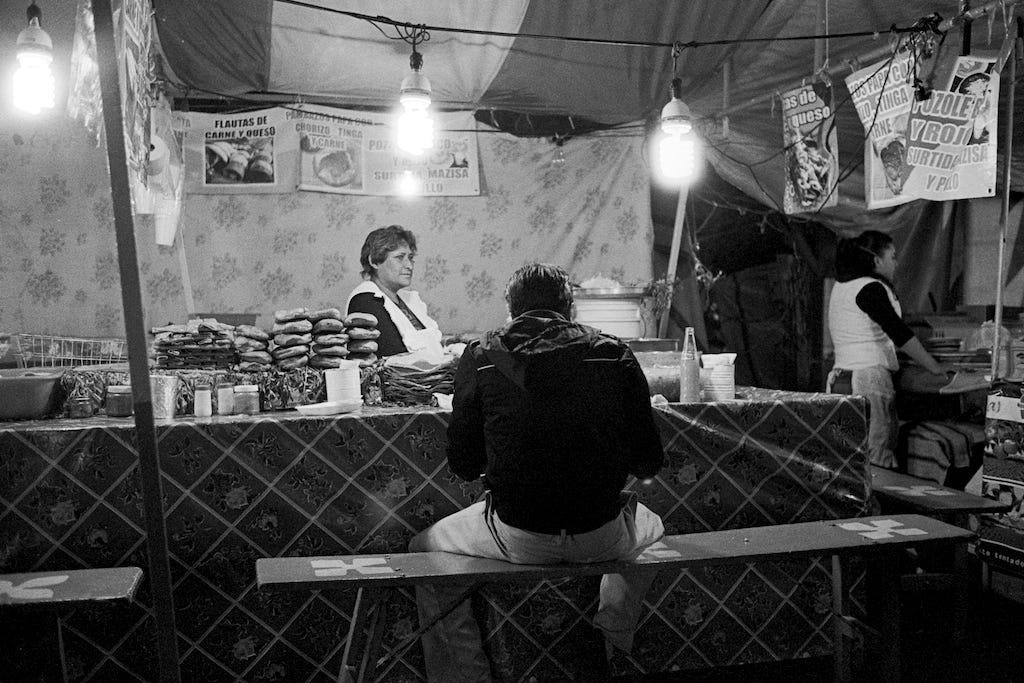

It’s very easy to idealize Mexico City. To paint it as a tourist destination for fans of Roberto Bolaño. To present its hippest neighborhoods as epitomes of a cosmopolitanism that hasn’t turned its back on tradition. All that is complete bullshit. Aside from the three or four neighborhoods where the emerging middle class lives, Mexico City is essentially ugly. You have to embrace that ugliness, to find its charm without betraying it. You have to listen to Witold Gombrowicz, who praised the grimy immaturity of Buenos Aires — the vileness of the slums — over the brightly lit, pseudo-European boulevards.

Typical Mexico City is not the combination of blue and sienna of the Frida Kahlo house in Coyoacán but the unpainted gray and exposed rebar of the ocean of houses that spreads around Calzada Ignacio Zaragoza as you leave town headed for Puebla. It’s a city where there are hair salons and pet stores that make payoffs to the drug cartels in order to dye gray hairs and sell hamsters. Women can’t dress the way they like or take public transportation without having their asses grabbed. There are zones of extreme poverty next to office buildings where the CEOs arrive in helicopters. There are daily protests because the government can’t fathom why people are so intent on having decent jobs. There are whole neighborhoods that go without water for days. There are windy afternoons when a pungent stench of garbage blows in from the east. Every time it rains, the whole city floods and the storm drains spew shit. Every now and then a dismembered corpse appears in some sector of the city, or a body dangling from a bridge. There are human trafficking rings that hold captive dozens of teenagers and prostitute them with the connivance of the police. There are hundreds of SUVs filled with armed bodyguards who control the population by violence and with total impunity. There are millionaires, in some neighborhoods, who pay considerable bribes to the right public official in order to have the air traffic over the city rerouted so that the noise won’t disturb them when they’re watching American TV series in their home theaters.

I’m madly in love with Mexico City, crisscrossed as it is by low-flying planes, which I sometimes imagine dropping bombs.

In August 2015 I emigrated to Montreal because I could no longer write in Mexico City. That wasn’t the only reason, of course, but it’s the one I choose to tell about. It’s impossible to find the time to write if you’re working nine or ten hours a day, and given the state of the Mexican economy, it’s impossible to survive if you’re not working nine or ten hours a day. In this context, writers from well-off families have more opportunities. Of course, in comparison to the country as a whole, I wasn’t bad off, even if I did come from a solidly middle-class family of university professors and not one of businessmen. Female writers who come from rural areas and write in indigenous languages are condemned to a marginality infinitely greater than mine. I’m white, male, relatively heterosexual and a capitalino — a capital-dweller — in a country that’s racist, criminally poor and covered with unmarked mass graves.

In the Monstrous City there always seem to be more important things to do — anything but write a book! There are parties that can’t wait. There are art exhibitions where a section of the museum gets blown up. There are demonstrations which you ought to join in protesting the disappearance of dozens of people. People abducted by a UFO, perhaps, or more likely massacred by the state in collusion with the narcos. And in the dead hours there are friendships and absurd plans that end up winning me over, uprooting the idea of spending the next five hours in front of a computer. (The plan, for example, of watching the sky from a roof terrace in Colonia Narvarte at three or four in the afternoon on a Sunday, three hours after ingesting half a dose of LSD.)

Writing in Mexico City, for me, was hardly ever writing.

Writing in Mexico City, for me, was hardly ever writing. Letting weeks pass without adding a single paragraph to the novel. Typing up commissioned pieces in two and a half hours before heading out to interminable dinners that degenerated into karaoke. Walking at dawn in search of a taxi. Listening to the airplanes overhead and thinking of the novel that I wasn’t writing, that I might never write.

Nowhere have I felt so part of a community as in Mexico City. But every community has its dark underside. Noise, constant and deaf, like an airplane that’s always passing and never passes, hangs over Mexico City and forces me to stay silent. And every so often this dark certainty, like the shadow of an airplane, flies over my spirit: literature is incompatible with literary people.

The effect of the LSD is fading. The afternoon too. There’s a rose color at the edge of the sky and an impossible orange in a few of the clouds. “It’s the drug,” I think, but it’s also the chromatic spectrum of the air pollutants, which can convert Mexico City into one of Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams. There are fewer airplanes now, but the three of us have stopped talking anyway. Sundays in Colonia Narvarte have always struck me as cruelly melancholic.

I say goodbye to Benjamín and Jorge and set off on my final walk home. But then I remember that my home is 3,000 miles away, and so I walk aimlessly, through empty streets, until night falls.

About the Author

Daniel Saldaña París is an essayist, poet and novelist whose work has been translated into English, French, and Swedish and anthologized, most recently in Mexico20: New Voices, Old Traditions, published in the UK by Pushkin Press. Among Strange Victims is his first novel to appear in the US. He lives in Montreal.

About the Translator

Philip K. Zimmerman is a writer and a translator from Spanish and German. Born in Madrid, he was raised in Upstate New York. His work has been included in the Berlin International Literature Festival and the New York International Fringe Festival, and he recently completed a translation of Helene and Wolfgang Beltracchi’s autobiography, Selbstporträt (Self-Portrait). He lives in Munich, Germany.