Books & Culture

Postmodern Literature Is the Best Expression of What It’s Like to Be Autistic

The scattered plots and timelines of books like “Infinite Jest” make sense with the way I experience the world

I’m in a college lit class and the professor is talking about postmodern literature. “It’s alphabet soup,” he says. “It’s made by white men for other white men to feel smarter.” He’s a white man, himself.

Everyone in the class nods. These are smart people, diverse. I don’t feel like I belong here with them. Sometimes I’m oblivious to the difference, other times I notice things. For one, they don’t twitch, their shoulders don’t bounce up toward the ceiling in short waves, their fingers don’t pound out 4/4 beats on their jeans. Most noticeably, they all look better than me, more put together. I can’t seem to dress myself properly. I wear the same shirt three days in a row, put on baseball caps so I don’t have to wash my hair every day. I stop wearing contacts because it irritates my eyes and I don’t care enough about the way I look to put them in.

I nod along with the class, take notes, write “alphabet soup” in my notebook. I don’t raise my hand to argue because they’re right; postmodernism is trash, it’s garbage literature. It’s too white, too male, too wannabe-intellectual, too self-important, too distant from its subject characters because it’s scared of sincerity.

But still, secretly despite all of those issues, I love it.

I love it because it’s me.

It’s too white, too male, too wannabe-intellectual, too self-important. But I love it because it’s me.

I don’t fully realize that I’m autistic until I’m an adult, though I’ve joked about it for a long time.

“It’s not my fault, I’m probably autistic or something,” I say to justify the way I act, the missed social cues, the mind fogs. We laugh. It’s funny.

Or, it’s supposed to be.

We’re not a family who acknowledges things, talks about them. My dad’s family is repressed, unable to communicate even the most basic feelings to each other. My mom’s family has mental illness, drug abuse both prescribed and not, more than one death because of it. What’s a few quirks, a few outbursts, a lot of frustration in the scheme of things? At least I’m still around.

I teach at a school for children with autism. This is where it sinks in, where I finally understand. I recognize myself in these kids, but it scares me. Is this how everyone sees me? Is this how strange I am? How transparent? How frustrating?

One of my students kicks low, aiming for the shins. He has a pencil in his hand that he swings at me. I manage to get it out of his hands before he can do any damage. It isn’t the first time, a pencil has gone through my shoe and into my foot. It’ll happen again.

It takes him an hour to calm down, his face white, colorless. You can see regret in his eyes, shame for the part of his brain that made him go off, took away his control.

“My cousin says I can’t join the military because I’m autistic,” he says. “He told me my mind doesn’t work right.”

He begins to cry. It’s a long time before he’s done.

I tell his mom about the incident when she picks him up at the end of the day, her newborn in her arms. “The thing with his cousin and the army? He’s still on about that? That happened, like… three months ago,” she says.

I think about my other students who ask me if I remember an episode of a TV show they like, as if I had been there when they watched it. I think about the kids who watch Youtube clips for hours straight without realizing how long it’s been, the same ones over and over and over.

They can’t always decipher place or time. It all moves together, blends at the edges.

“He didn’t hurt you, did he?” she asks, looking me up and down, trying to spot the damage her son might have done.

“No,” I say, smiling. “Not this time.”

In 5th grade, my teacher asks if anyone knows who Nixon is. I raise my hand and proceed to walk the class through what I perceive as an intelligent explanation of Watergate, only to realize near the end that she had actually asked about Reagan. My freshman year of college I trip over a classmate’s computer cord while walking into class late, causing her computer to fly off the desk. I tell everyone in my life that I can’t swim, and they think I’m joking until they realize I mean it, and then they laugh at me. All of these things are happening right now, all the time. It’s continuous.

Every time I’m embarrassed I can feel an entire life’s worth of embarrassing moments dangling behind me, out of reach, but not out of sight. They cycle through my head, like the end of a mystery movie where they flash back to all of the scenes that pointed at the culprit, the things that seem so obvious now, that you can’t believe you didn’t catch the first time through.

Every time I’m embarrassed I can feel an entire life’s worth of embarrassing moments dangling behind me, out of reach, but not out of sight.

Everything in my mind is connected. It’s never one thing, it all reminds me of other people, of songs, of places, of past moments. I live in my head, I drift off, I don’t hear people when they speak to me, I talk to myself under my breath as I remember a conversation, as my mind plays out conversations I might have.

The only thing that gets lost is the present.

When I’m thirteen, I read Slaughterhouse-Five. It’s probably the first time I read something that I’d consider postmodern, unless you want to count The Stinky Cheese Man, which you probably should. I read it in one sitting, the story clutching me, not letting me leave. I’ve read books I’ve loved, but they aren’t like this. The Perks of Being a Wallflower is my favorite, as close as I’ve come to seeing a character who’s like me, who has panic attacks that feel real, whose social anxieties aren’t fun or cute but crippling, infuriating. But that book is still wish fulfillment; Charlie, the main character, has friends, a social life, a mentor. A lot of bad things happen to him, but I can only focus on the good things, the ones I can’t imagine ever happening to me.

But Slaughterhouse-Five is different. I don’t exactly see myself Billy Pilgrim, the book’s protagonist. But the writing, the language, the world, the structure of the novel: it’s my brain. It’s like seeing the contents of my head projected in front of my eyes.

In the book, Billy Pilgrim becomes “unstuck in time,” the story bouncing around the events of his life, from his time fighting during World War II, to his marriage, to his capture by aliens. He can’t keep himself in one spot, even if he wants to. This is how I feel: made to time travel by force, to never focus on a single event without being buried by the ones that have happened, troubled by the ones that might happen in the future.

I see memes about people not being in the moment, spending too much time on their phones, not really living. I try to do this, to focus on important moments, to make my mind still, to really experience my life as it happens.

But I’m not allowed. I always slip away.

My wife, Hannah, gasps as we pull into her mom’s driveway, Eevee, her Persian cat, sitting in the window. She does this every time.

“Don’t do that,” I say, clutching my heart in mock it’s the big one fashion. “Scares the shit out of me.”

“Can’t help it,” she says, shrugging. “Eevee is just so beautiful.”

I wonder about the post-modernists, if they have the problem that I have, if access to certain feelings was difficult, like they were always reaching for it. I read Pynchon, Delillo, and everyone talks the same. Characters are there for purpose of the idea.

One day, Hannah and I are walking together through the mall. I do my best to do tell her how I wish I could do what she does, act excited, gasp, show things.

“You do,” she says.

“What do I do?”

“Your eyes get bigger. You say something monotone, like, ‘That’s pretty cool.’ It’s usually subtle, but I see it.” She squeezes my hand, pumps one, two, three. “It’s there.”

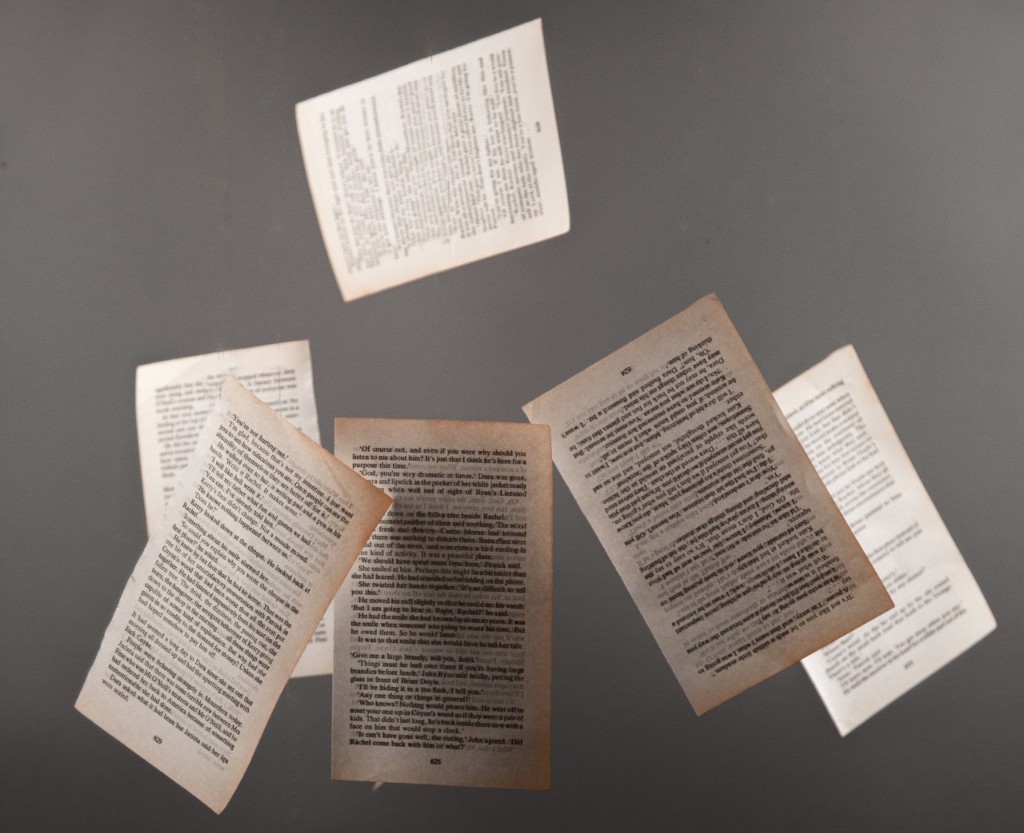

My copy of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest is beaten up, the pages loose. I’m obsessed with keeping my book collection in perfect condition so the fact that this is one of the only novels in my collection that has highlighted passages means something.

I read articles about women who are tired of men forcing them to read it, of how it’s a cornerstone of white male pseudo-intellectualism. Oncea month I see different satirical article that uses interest in the book as shorthand for a guy being a pretentious douche-bag who likes to mansplain how stocks work or who orders meal for his dates without asking.

It’s one of my favorite books.

To me, reading Infinite Jest feels like watching gold medal gymnasts, the words flying around, dancing across the page. It leaves me frenzied, breathless. The plot is scattered, broken, forcing me to pay close attention to each detail, to put everything together on my own. Each character gets their own section of the novel to shine, to have their story told. Some are funny, almost silly. Some are heartbreaking. Most are both.

When I read D.T. Max’s biography of Wallace, Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, I see that Wallace is a lot of the things that people accuse his followers of being; that he was a deeply troublesome person, had inappropriate interactions with women, wasn’t a saint by any means.

But I realize at a young age that I want to write books like him, like other writers with a similar style.

I have unfinished novels, a dozen of them. I get enthusiastic and then I trail off, the chapters go on tangents, my cast grows and grows until the book can’t be contained. I have separate documents on my computer with timelines so that I can keep time jumps and character arcs straight. I cut out sections in an attempt to streamline, only to add more because I have to, because it’s where my mind goes. I want the books I write to be everything that I am, include all the parts that make up me. I see that this is what Infinite Jest is, or at least what it tries to do. It may have had pretentious intent, the idea that you can write a book and just put everything in it. But that’s how I feel sometimes, it’s all in there, and I have to get it out.

I have to put it somewhere.

I want the books I write to be everything that I am, include all the parts that make up me.

I worry about having children. I worry about not understanding their needs. I worry about failing them. I worry they won’t be happy. I worry about not having time to read, time to write. I worry about not having a way out.

Most of all I worry that they’ll be like me.

The first band I like is Fleetwood Mac. I hear “Go Your Own Way” on the radio, think it’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me. I listen to my parents’ copies of Rumours and The Dance over and over on a set of face-swallowing stereo headphones.

I don’t know what’s cool, what critics like. Later, I’ll find out that none of my friends like Fleetwood Mac, they like the Backstreet Boys or Britney Spears. They don’t like comic books either, think they’re silly compared to their Pokemon cards, to the Gameboys that they hover around during recess. I want to abandon my interests, trade them in to be more like my classmates.

I would if I could.

I don’t want to go back to not knowing what people think, to living in a bubble, to being deaf to other people’s voices. But I can’t change the things that have become a part of me either. As much as I would like to, I can’t take a different path, can’t make things different.

Sometimes, in my worst moments, I wish I could change me, the way I am. But it’s always there, like everything, dangling behind me.

Never out of sight.

“What’s it about?” Hannah asks. It’s Christmas Eve, her brother and his girlfriend in the backseat. I’m driving, my least favorite activity, trying to pretend that I’m not terrified of the blizzard that we’re driving through. The topic of long books has come up, and she’s asking about Infinite Jest, which she’s seen me reading before.

“Hard to describe,” I say. “There’s a video that kills people, a tennis academy, a ton of endnotes.”

“Should I read it?”

I shrug, stopping at a red light, managing to not slide into the intersection.

“It’s long as shit,” she says.

“It’s like me.” I say. “Frustrating and difficult at first, but it rewards you if you put the effort in.”

I look over at her, see the red light reflected in her eyes as she rolls them. This is how I am; I make the same jokes over and over, I make the same comments about songs on the radio. Hannah knows she’ll hear this one again, just like I know that this has happened before, will continue happening. The moments fold over each other, but never disappear.

I try to focus on Hannah’s face. I want to take a picture in my mind, keep this moment forever. I want to be here.

But then the light turns green. And I drive us home.