Craft

Queering Gender, Queering Genre

On being both, neither, and trying to still exist

I think I’m a woman, because I know I’m not a man.

I also think I’m an essayist because I know I’m not a poet (or a short story writer).

Whenever I submit my writing, I say I’m submitting weird essay/poem things and that feels most authentic. My pieces are probably closest to lyric essays, or prose poems, and have been published as either. Sometimes I submit a piece as an essay and it is called a poem upon publication. Sometimes, the opposite occurs. I never care, because I don’t understand labels when it comes to literature.

When binary is the norm, when she/her means woman, when line breaks mean poem, I am who I am perceived to be more often than I am who I am — especially when I have no idea who I am, and don’t completely care about it.

This is not the first time I’ve felt like two hypocrites live in my body.

Gender is a complex and nuanced thing and there is no way to make a sweeping statement about what it means to everyone. Some say it doesn’t exist. Some say it is a means to control. Some say it is empowerment. Some say it is everything. For me, it is not everything, not just because I’m cis (well, I guess?) and have cis privilege and am ignoring the role gender perception plays in society. I’d be ridiculous to act as if gender doesn’t matter in the world. But it doesn’t matter in my small, small world, in my body, in my head, not mine, not to me.

I feel the same way about genre. To some people, genre is everything. They are a poet in a big way, or a novelist. I write novels and poems and essays and, to me, they are all the same and different at the same time. I am into contradictions because I am one. I guess that being mixed but called Black made me ready for such an existence. This is not the first time I’ve felt like two hypocrites live in my body.

In Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive, Julia Serano complicates long held understandings of gender. Defining gender as “an amalgamation of bodies, identities, and behaviors, some of which develop organically and others which are shaped by language and culture,” Serano greatly disagrees with binaristic and even much of third-wave feminism’s gender isn’t real and is only oppression understanding of gender and believes it to be an oversimplification. Too, it is extremely dismissive of the experience of trans people who identify as men or women. The idea that gender is only ever oppressive results in a lot of the “but trans women perpetuate stereotypical femininity!” and femmephobia that we see on a regular basis within the feminist community.

The idea that gender is only ever oppressive results in a lot of the “but trans women perpetuate stereotypical femininity!” and femmephobia that we see on a regular basis within the feminist community.

Serano pushes us to accept the messiness of gender instead of trying to cut it down to a single answer, as cutting down to a single answer often means cutting out the most marginalized of people.

What empowers one disempowers another. Both can exist at the same time — no one understanding has to win. Just as I identify as black and mixed, queer and bi, I know I write poems that are essays and essays that are poems. There is, for me, validity to be found in space less easily labeled.

In the introduction of Lori B. Girshick’s Transgender Voices: Beyond Women and Men, Girshick writes, “As for gender-variant people, no conceptual framework fits their experience, and no individual words adequately describe it.” The section goes on to describe Reid, a FtM person seeking to communicate his identity. Reid’s quoted saying, “I now say that, rather than transitioning from female to male, I’ve transitioned female to not-female. English is inadequate to the task!”

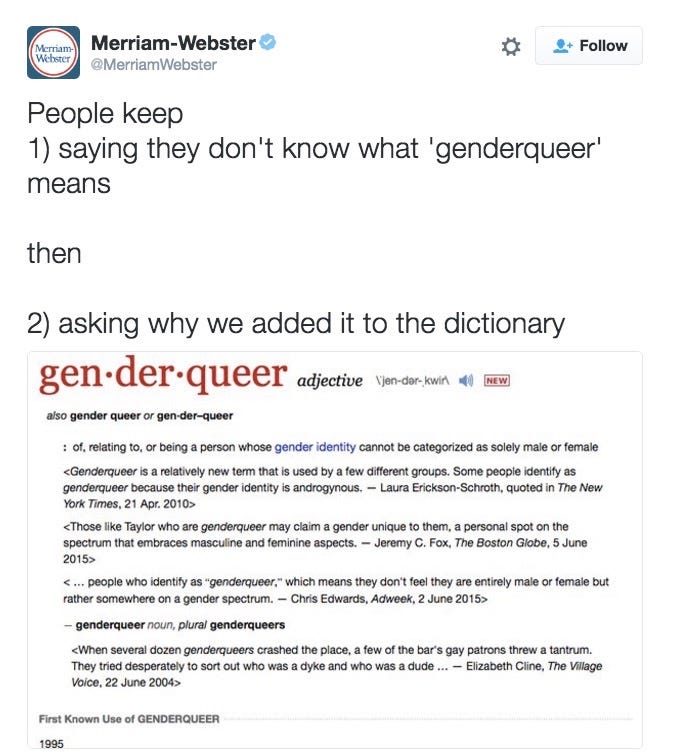

Remember the snark that went down when Merriam-Webster added “genderqueer” to the dictionary?

Words fail, especially when it comes to giving voice to experiences of marginalized people. English was not developed to empower all, and we see, regularly, the backlash against the creation of new words. From bae to pansexual, people pretty much freak out any time a new word is introduced to mainstream vocabulary. Remember the snark that went down when Merriam-Webster added “genderqueer” to the dictionary?

And this snark comes from writers, too, those writers we sometimes loathe and sometimes are, battling for the “right” words not to be taken down by the “made up” words we just aren’t used to, yet. Scoffing each time a new letter is added to LGBT doesn’t make you a true proponent of the English language — it makes you an asshole.

I was in a nonfiction workshop when my professor began mocking me for using too many words. I was writing about what it means to be both queer and mixed, and to constantly feel in-between and invalidated by language and mainstream understanding of identity. My professor was frustrated by my refusal? Inability? to “just say what I mean.” To be simple. Why complicate everything? If the only power I have as a writer is my pen, why muck things up by beating around the bush? I was flustered and unable — literally, as is the workshop model — to explain that I am found solely in the “around the bush area,” not within the bush itself.

I was in a nonfiction workshop when my professor began mocking me for using too many words.

If I say, “I’m a woman,” I feel as inauthentic as I do as I do when I say, “I’m gay.” Not because I’m not either of those, but because it doesn’t mean what other people think I mean. What is writing if not a means of mucking up language and syntax and fusing words to create new sound to better illustrate a lived experience rarely verbalized?

Why are we so afraid to let things be complicated?

I dropped the workshop, and still haven’t written that piece.

In Excluded, Serano defines essentialism as “the belief that all members of a particular group must share some particular characteristic or set of characteristics in order to be considered a legitimate member of that group.” I am interested in the ways that a non-essentialist approach to gender, meaning one that recognizes the space for duplicity of gender, gives room for someone to be both non-binary and a woman. As a gender-questioning woman writer who has tagged much of my work as queer (but meaning only sexuality, not sex or gender) and woman, I see a sort of comfort in this concept. If it is possible to be both non-binary and woman, than a non-binary writer does not need to be kicked out of a community of women writers, or out of spaces for women’s writing. They/we are, simply, both.

Just as I don’t want to identify as non-binary, regardless of the potential room for accuracy, I don’t want to identify as a “writer of neither genres.”

I wonder about this in terms of genre. Just as I don’t want to identify as non-binary, regardless of the potential room for accuracy, I don’t want to identify as a “writer of neither genres.” But how much does want matter when perception is what labels us in the mainstream?

If I am published, will anyone find my work if I don’t label it within a genre? If I am published, will I be known as a lesbian black woman writer? Or a queer person of color? Does it not come down to the most marketable term? Who am I if who I am depends on how many hits my identity would garner online?

In a 2012 Brevity essay, “The Craft of Writing Queer,” Barrie Jean Borich talks about finding space for queerness within the inherent strangeness of creative nonfiction.

What I’ve loved, from the start, about CNF has been the ways this genre is creatively weird, much like myself — both misunderstood and claimed by more than one constituency, attentive to form but difficult to classify, with quirky yet intentionally designed exteriors, slippery rules, a mutating understanding of identity, a commitment to getting past the bullshit and making unexpected connections, and a grounding in an unmasked, yet lyric, voice.

This is the piece that convinced me that maybe, if I hadn’t found my home as a fiction writer, I may do so in the “queer city” of creative nonfiction. It was that, the “unmasked, yet lyric, voice” that I knew I could write. It is a thing that frustrates other writers who tell me my essays are prose poems or that my poems should be essays or that my narrator should have interacted with more men throughout the piece to tamper down the emotions. I am told I cannot do what I do, but I do it. Again, contradictions make up my understanding of what it means to write.

I wonder what it would be like to write within a genre, to read the rule books and to value the canon and to do what I am told, just like I wonder what it would be like to have remained straight, to have dated men and just wondered about women the way I wonder what a line break and an indent and a smudge of erasure would do to my essays. I wonder about the space between rules of writing and rules of sex, and gender. I wonder about my space within that space, and whether I’ll always be okay existing within grey matter. I am not sure.