interviews

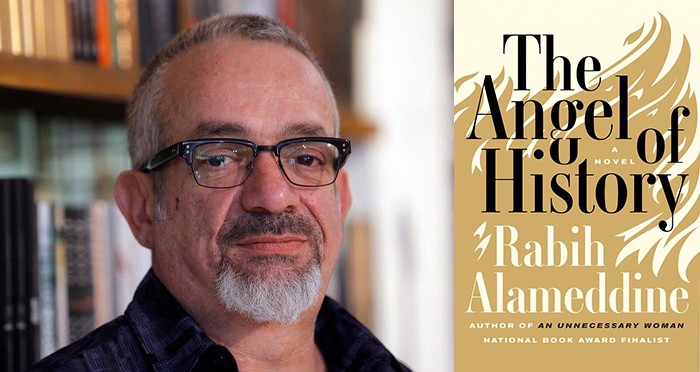

Rabih Alameddine Is Angry

The Angel of History author on AIDS, drones & political fiction

Rabih Alameddine is angry — he’ll tell you that himself — but it’s a useful kind of anger. An anger that rages against the dominant narrative, whether that comes in the form of American foreign policy, societal responses to AIDS victims and the LGBT community, or contemporary MFA literary stylings. If he has a strong opinion about something, by God he’ll let it out. Holding his tongue on an issue for fear of alienating a potential reader or sacrificing a potential sale has never been high on his list of priorities, and the tremendous commercial and critical success of 2014’s An Unnecessary Woman, which was a finalist for both the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award, has done little to change that. “Fuck the reader,” he said in a recent interview, “A lot of writers say it’s about communication. It isn’t. I write for me. I write because I have something to say to me.”

If this paints a severe picture of the man, it shouldn’t. Alameddine is, as I found out recently when we sat down to chat in the lobby of Manhattan’s Walker Hotel, fantastic company. Possessing of fiery opinions, sure, but also refreshingly candid, quick to laugh, and generous in his responses. We spoke about writing as a political act, the most daring authors at work today, his time spent in Syrian refugee camps in Lebanon and Greece, and the challenges and pleasures involved in the writing of his new novel, The Angel of History — an intense, fragmented portrait of a man in emotional and psychological crisis. Set over the course of one night in the waiting room of a psychiatric clinic, the novel follows Yemeni-born poet Jacob as he revisits the events of his life, from his formative years in the Egyptian whorehouse where his mother worked, to his experiences as a gay Arab man in San Francisco at the height of AIDS. Peppered throughout are wise-cracking conversations between Satan, Death, and the fourteen Saints that have watched over Jacob throughout his tumultuous life.

Dan Sheehan: In an early restaurant scene, Jacob explodes at two young gay men, enraged at how little they appreciate the incalculable loss that the previous generation experienced. To what degree do you share Jacob’s anger at the way the memory of the worst of the AIDS years is slipping from the public consciousness, particularly amid the younger generation?

Rabih Alameddine: Quite a bit. I mean, I’m not Jacob, there are many things that are different between us, but that feeling of rage is the reason why I started the book. I remember a similar incident, but it wasn’t about somebody dying. Two very good friends invited me over for my birthday dinner and I spent the entire evening screaming at them about the ‘It Gets Better’ videos. I just lost it. And I wasn’t angry with them, I was just trying to explain why these things upset me. About an hour in to it one of them looks at me and says, “well, this is a happy birthday isn’t it” [laughs]. I realized then that I was so angry, but it took a while for me to figure out what I was angry about. I would watch the ‘It Gets Better’ videos and I would be furious that we are telling these kids that life will get better. Life didn’t get better for those of us who went through the AIDS crisis. It never got better. It got worse and worse and worse. If you’re getting beaten up now, it doesn’t get better. We would never tell a woman who has been assaulted “don’t worry, it’ll get better” but for young gay boys and girls who are getting assaulted, we do. Stuff like that was driving me crazy and I couldn’t figure out exactly why. I started getting upset about drone attacks — another thing we pretend we care about. All these people were dying and nobody was paying any attention, and I started freaking out. It took some time to understand that my rage was directed at me, because I had put everything aside for a while.

DS: Was there are a catharsis then, in the writing of this book?

RA: I don’t believe in catharsis. I’m not a big believer in the romantic idea that art can heal. What it does do is bring things to the surface, and then I go see my psychiatrist [laughs]. For a while there I was seeing him about four times a week. I jokingly once said that I see a psychiatrist to solve the problems that are exacerbated by writing. So no, it’s not a catharsis. But I suppose it depends on how you define ‘catharsis.’ Bringing these issues to the surface could be considered cathartic, but it doesn’t solve the problem.

DS: The way that the novel is broken up into so many fragments seems to resist a single, easily digestible reading. It addresses, among many other issues, the value of traumatic memory, the devastating impact of AIDS in America, US drone strikes in Yemen, and the fetishizing and dehumanizing of Arab men. Can you tell me a little bit about the significance of this expansive, mosaic approach?

RA: One of the things that happens with me is that, so far, every book I write is not just in response to the last book, but it rebellion against it. The response to the last book somewhat surprised me, I did not expect people to like it that much, and I don’t expect people to like this one that much!

DS: How fun was it to take on Satan and Death as fictional characters? Taking the baton from Milton and Bulgakov. Was it something that you’d always wanted to do?

RA: For me, it was the most fun section. Even though there were some passages that proved difficult, for the most part the interviews were the easiest to write. I’ve always been fascinated by Satan as a character. Milton is not the funniest of writers, but Bulgakov was and yet I don’t know if my character was based on that version, even though I am such a big fan. What I was more interested in was the idea of Satan not being either a good guy or a bad guy, but rather being the guy who, at the end, says “all those who say ‘no,’ follow me.” As the one who refuses to follow the dominant culture. So in my mind he became the saint of not just gay men, but of all outsiders. The guy who says ‘no.’ So it fit into the whole idea of revolution — that some of us just say ‘no.’ And that’s where the character started taking shape as someone who just likes to fuck with people. The idea of good and evil never entered the picture really.

DS: This wonderfully entertaining back-and-forth between Satan and Death — between the dredging up of painful memories and the deadening repression of those memories — is so interesting because, for me, it seems like they both have a fair point. To bury all the pain of your past is to live a sort of disconnected half-life, but to fully engage with it, especially when that past is as traumatic as Jacob’s, would be too much for most people to bear. Do you think there’s something to be gained from landing somewhere in between these two stances?

RA: Of course. If I remembered everything, I’d be dead. It’s as simple as that. I specifically remember 1996 when my last friend died and things started to get a little better because we had access to drug cocktails. It wasn’t a conscious decision to say, “oh, I’m going to forget everything,” but I did put certain things aside, and I started writing my first book, which was about the AIDS crisis. If I hadn’t put those things aside, I would not have been able to progress. I would not have become a writer. But then, if you forget everything, you end up working for Trump. Where we fall on this spectrum is what I’m interested in, and I don’t have an answer. At one point Satan says, ‘well, it’s a dance, but I’d like to lead for a while,’ and that’s basically it. For the most part we live in a culture where we are constantly encouraged to forget. We go to war and then we completely forget that we’re in a war. But if we remembered everything, we’d go insane. So it’s somewhere in between.

DS: A recent Guardian review said of Angel: “Here is a book, full of story, unrepentantly political at every level. At a time when many western writers seem to be in retreat from saying anything that could be construed as political, Alameddine says it all, shamelessly, gloriously and, realized like his Satan, in the most stylish of forms.” Do you see yourself as a heavily political writer, or is this a mantle that critics have tended to thrust upon you because you’re Lebanese-American?

RA: Well, yes, I am a political writer. I remember being asked a question on a panel — which I hate, by the way, because I find panels incredibly stupid — called ‘Political Fiction,’ or something, and why they put me in there I don’t know, because it was to discuss An Unnecessary Woman, probably my least overtly political novel. Anyway, I went into one of my…tirades, shall we call them. I’ve been doing that a lot lately. I said, “what do you mean by ‘political fiction’? What fiction is not political?” The trouble with the United States is that there is this delusion that the written word can ever not be political, and that if something is political, it is somehow less than. I’ve said this one hundred times and I’ll say it again: if your country is dropping bombs in Yemen and you decide to write about a woman in Beirut who is seventy-two and doesn’t leave her house, that is a political book. If your country’s policemen are shooting unarmed black men on the street, and you write about a white couple in Minneapolis, that is a political decision. To write about the human condition is political; it’s one of the greatest political acts. Art has never been apolitical.

To write about the human condition is political; it’s one of the greatest political acts. Art has never been apolitical.

DS: So it’s just then a case of owning your politics after you’ve written them?

RA: And understanding your politics. I believe that walking down the street is a political act, we just never think of it that way. Seriously, everything is political. Now, this book is an overtly political novel in that Satan, Death and Jacob all state their political views, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Even when I write a novel about storytelling or about a woman having a nervous breakdown, I am still being political because we are political beings. The delusion is that we’re separate from all of this. We’re not.

DS: Authors are notoriously cagey when it comes to writing about sex. The specter of the Bad Sex Award seems to loom large, and even when writers do write sex scenes head on, it’s rare to find one that is integral to the plot or conveys any real emotional substance. Yet one of the most significant, and heartbreaking, moments in your novel is a graphic depiction of sadomasochistic sex with a stranger in a bondage dungeon. How do you approach writing sex scenes that are crucial to our understanding of a character’s development rather than just window dressing?

RA: I have no clue [laughs]. First off, it takes the ability to put what everyone thinks aside, and also to put what I think aside. When I wrote that chapter I seriously thought that it was going to kill the book. I mean, An Unnecessary Woman was received so well; I remember being at a festival in Adelaide where about three hundred or four hundred women came to my event and I looked out and I saw white hair everywhere and I thought I have a new audience! And then immediately afterward I thought what the hell are they going to think about that scene? [laughs]

I have this young writer friend who asked to read the book so I gave it to her in an early draft and she read it, and I wanted so badly to know what her response was, expecting her to be appalled. But she said that she loved the book, and of course my response then was ‘yes, yes, but what did you think about that scene? Were you shocked?’ and she just said ‘well, it’s not like I haven’t done some things.’ And the response from my publisher and others has also been ‘oh this is such a great scene,’ so I realized that maybe I’m still living in the 70’s and 80’s, thinking I’m being provocative, when maybe it’s all become common. We just don’t see it in contemporary fiction. We see nothing in contemporary fiction, except couples in Minneapolis.

We just don’t see it in contemporary fiction. We see nothing in contemporary fiction, except couples in Minneapolis.

DS: So who are the exceptions to that, for you? Who are the daring writers at work today?

RA: Sasha Hemon is one of my favorites. Junot Diaz for sure. I love Claudia Rankine and a number of young gay poets. I’m a big fan of that Irish boy, Colm Toibin [laughs]. He’s a close friend and one of my favorite people. It’s both about adventurousness and craft. What I like is someone who is giving me something that I haven’t seen before, and usually these are people who, even if they have gone through an MFA, they’ve somehow survived it. Most writers who go through an MFA program, for a long time their voice becomes the same. Oh they produce beautiful writing, but I hate beautiful writing.

DS: You recently spent some time in a number of Syrian refugee camps, both in Lebanon and Greece. Can you tell me a little bit about that experience?

RA: Well, I started because I was upset. There are one and a half million Syrian refugees in Lebanon and I just wanted to hear some of their stories. I wanted to talk to people. So for a while I was nothing more than a witness. And I wondered how helpful I was being, but I suppose I was helpful in the sense of ‘I’m here, I’m recording this, I’m hearing your story.’ And I don’t know how important it was for them, but I can say that it was interesting how many were willing to talk. It was only the people who were tortured who were not really willing, and I completely understand that. I had a different experience when I went to Lesbos, because I wanted to see exactly what was happening. That was traumatic, and it wasn’t just because of the refugees; it was a combination of the refugees and the disaster tourism: Volunteers, there to receive the boats, taking selfies as the boats were coming in.

Then of course I had to go through the entire process of saying, ‘well, what am I doing that is different to what they are doing?’ And one of the things that I realized is that I do it because I want to be someone who helps, and I want to be seen as someone who helps. So it’s the same thing; they’re just taking it the extra step by putting a selfie up. But it was difficult. As were other aspects. I mean, in Lebanon, for the most part, refugees integrate into society in one way or another. In Lesbos, aside from the fact that it was just a stopover, the feel of the place was more that of a prison camp. Police in riot gear, barbed wire. It’s supposed to be a safe place, but there were police in riot gear at the bottom of the hill.

DS: So there was no effort being made to give them a sense of even temporary home?

RA: Some, some effort. But again, there were police in riot gear at the bottom of the hill. How at home can you possibly feel when you’re surrounded by walls with barbed wire on top?