interviews

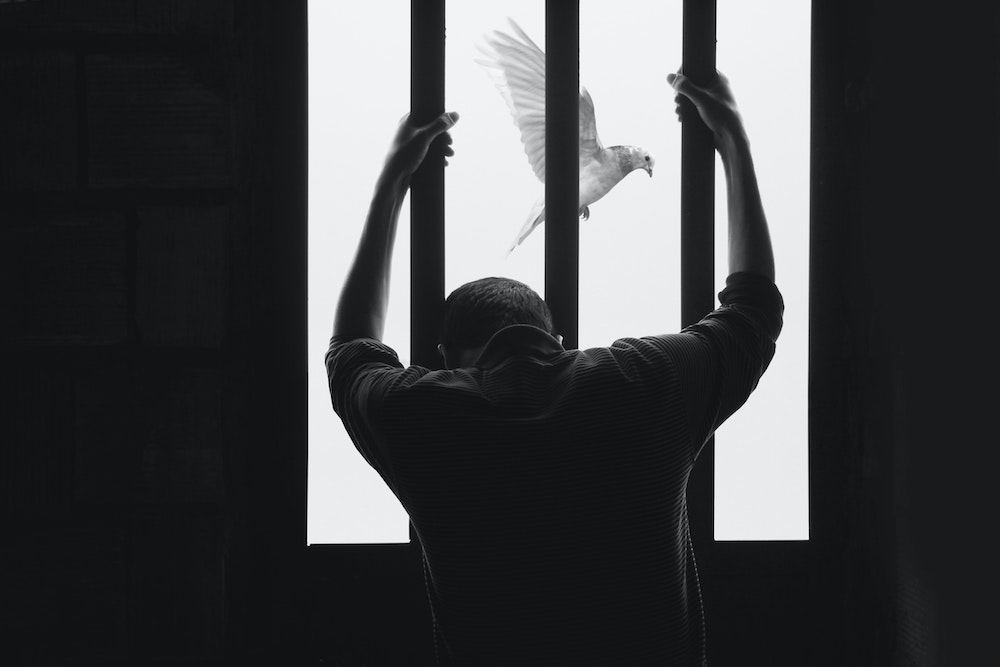

Rachel Kushner Thinks Prisons Should Only Exist in Fiction

The author of “The Mars Room” on prison abolition, the effect of poverty on crime, and how this all relates to her novel

Rachel Kushner’s latest novel, The Mars Room, begins as Romy Hall enters the Stanville Women’s Correctional Facility for two consecutive life sentences after killing her stalker. As the novel unfolds, Kushner lays out Romy’s life in Stanville, and the lives of her peers—with no veneer over the brutalities, both banal and crushing, that women prisoners face in the California prison system. Kushner does not paint Romy as a paragon of innocence; rather she subtly asks the reader to reconsider where our definitions of innocence and guilt are born.

Kushner is more than a writer and an academic: she is an advocate, who before, during, and after the writing of the novel works on the ground with prisoners and former prisoners to create networks for women who have little access to resources.

As I read The Mars Room, I thought about how much of what seems to be true of our society is a façade achieved by the privilege of being born into a safety net. I thought about how much we take for granted — the ability to plan for the future, a belief in justice, the idea that our choices determine our destiny. Kushner’s novel makes the reader ponder: who is forgiven for their mistakes, and who does society deem worthy of redemption? The answers that appear as The Mars Room unfolds are not uplifting or joyful, but they are necessary to understanding the large scale injustices of mass incarceration in the United States today. In The Mars Room, life in America is not one uniform story, but rather a series of connected universes that show how much of one’s life depends on the circumstances under which one is born and the care that one receives.

Kushner and I spoke on the phone about prison abolition, the relationships she’s developed with prisoners, and the ties between capitalism and the carceral system.

Rebecca Schuh: You have a line in the book, “People say your time hits you in waves. Mine was hitting me. I could see no way to accept this as life, to live it to the end.” What did you learn about developing strategies for living within that altered sense of time throughout your research with people in prisons?

Rachel Kushner: I don’t think that there’s an answer for people who are serving life sentences. People go through phases where sometimes they’re very focused on the day to day, and other times they feel desperate and boxed in. Some people decide to become heroin addicts because heroin is really easy to get in prison, I mean pretty easy to get — you have to make it a full time job if you want to be a drug addict. But it’s an option as a way to cope. I know that’s not a very uplifting answer.

When people talk about the thing that they were ultimately convicted of that resulted in their life sentence, it’s never that shocking. It’s logical.

Other people decide to pour everything into basically becoming jailhouse lawyers, representing their own case, doing petitions. Other people turn to religion, different kinds of religion, which actually can be quite helpful. And other people are angry and raw and hurt and they hurt themselves.

There aren’t happy answers to this. There is one woman I know in prison who’s an incredible gardener, and that’s been a really amazing thing to learn about. I met her on a prison yard in 2014, four, almost five years ago. They’re not supposed to grow anything. No plants are allowed, they chop everything down that’s over six inches high because they think people are going to hide drugs. But the guard on the yard let her garden after she had found a seedling and she germinated it and planted this tree. She has life without possibility of parole and she made this garden and it just seems so amazing to me, her name is Michele Scott and she later wrote an essay about it that I edited and included in this anthology Best American Nonrequired Reading. She’s a beautiful writer.

But I don’t know if there really are that many possibilities. Most of the ones I enumerated to you aren’t real escapes. If you become a drug addict in prison, eventually you will go to the secure housing unit or Ad Seg, you get in trouble all the time, then you get into fights, then your disciplinary record is all fucked up, then you get clean, then you feel guilty about everything, it’s these cycles of remorse and denial. I’m not sure if any of them really produce relief.

RS: There’s a passage where Romy is seemingly speaking directly to the reader and says, “Everything for you would have been different, but if you were me you would have done what I did.” I feel like most people assume that they would never end up in prison. I found myself, when I was reading about what led up to her sentence, I really understood exactly why she took the actions she did. How did you go about making the reader identify with the timeline that led up to Romy’s two life sentences?

RK: Are you sort of saying that she didn’t seem necessarily that “guilty” to you?

RS: You developed a really strong sense of empathy for her within the reader, to the point that whether or not she was guilty seemed like more of a function of the system she was in rather than the actions that she took.

RK: Yes. Yes. Thank you for saying that, I agree with you completely. When you watch a movie about mafia dons in Little Italy from the 1970s or something, the viewer starts to really strongly identify with the principal characters, whether or not what they’re doing is legal or harmful to other people. You’re rooting for them.

Prison seems to be broadly about sacrifice, rather than about rehabilitation.

So there are certain paradigms where criminality is something that, not only does it excite a viewer, but the so-called criminal is somehow immune from our moral judgment. Because the way that they proceed seems logical.

That has been my experience getting to know people who are serving life sentences. I’ve developed pretty in-depth relationships and dialogues with people inside prison who are separate from my book, and those relationships continue, and when people talk about the thing that they were ultimately convicted of that resulted in their life sentence, it’s never that shocking. It’s logical. Like one person was in a gang and she transacted a hit on a rival gang member. If you’re watching a movie about mafia dons and one person has to kill someone who’s been disloyal or whatever, you understand that that’s what’s happening next. And so in talking to people, I felt like their lives were as logical as anyone else’s lives, except that they all seemed to come from—I say this somewhat facetiously, it is not a coincidence—from a layer of the population that has no resources.

The person I know who transacted a gang hit was serially sexually abused by her father and stepfather, and was gay. So the trauma that leads to a sense of broken identity — one thing follows another for people. With the character Romy, I didn’t want to make the murder that she commits seem like self defense.

RS: Throughout your years of research, did you come to a personal philosophy of prison reform or prison abolition, and can you describe what your personal philosophy towards that is?

RK: To be honest, I had a personal philosophy prior to these last several years when I embarked on a personal project of involving myself in as a witness to the criminal justice system. I don’t really call what I was doing research, because it was where I wanted to be in my life at that moment. That life continues for me even though the book has been finished for 18 months. I’m on an advisory board of a group called Justice Now that advocates against human rights violations in women’s prisons, and I talk to people all the time in prison. I’m a believer in a really old-fashioned sort of activism that’s what I call a buddy system. There are people who can call me when they need to, and I try to help people in a one-on-one direct manner, and that’s why I can’t call it research. Those relationships continue.

It’s overwhelmingly very poor people who commit acts of bodily violence against society, and it’s not because those people are inherently prone to violence.

But my personal philosophy going into this was, I already was a prison abolitionist. And I continue to be that, although I think that the term warrants far more explanation than us abolitioners, as I call them, have been able to produce, and I hope to be one of the people who can work on that concept and movement with other abolitionists in the future. I’m going to be writing something very in-depth about it this fall.

Prison seems to be broadly about sacrifice, rather than about rehabilitation, and I haven’t really seen a paradigm for reform that convinces me. This is a little separate from my book it’s more political, but a lot of the conversation around mass incarceration has centered on people who are so-called non-violent low-level drug offenders, and only a small percentage of people in prison in California fit under that subcategory. Ninety percent have been convicted of what the state considers to be serious, violent felonies. So if we really want to reduce the prison population, we have to stand up for people who committed tough crimes, and I see abolition as the only real horizon for doing that, because it’s a way of asking for a world where we have state resources to focus on communities and help those communities to thrive so that people are aided long before they commit an act of harm.

RS: There’s a passage when Romy is working at The Mars Room about how strippers are expendable while the men who spend the money aren’t, and of course that got me thinking about capitalism. How much of the legal system do you think is rooted the fact that we are a capitalist society?

RK: Well, it is rooted in that. I just was interviewing the prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and after five days of conversation I asked her, “Can we abolish prisons without abolishing private property?” And she was quiet for a long time, and then she said “no.”

But I don’t think I have all the answers and I think that people who do claim that are charlatans. Capitalism is so complicated at this point. I’ve yet to see someone even convincingly define it. Clearly we have this incredible work that Foucault did to show us that the system of putting people into cages happens at a certain point, historically, it happens when people start roaming the countryside, because, after primitive accumulation then they’re alienated from their own labor because they have to use it to get money to buy stuff. All I know is that there are really almost no middle class people in prison. It’s overwhelmingly very poor people who commit acts of bodily violence against society, and it’s not because people are inherently prone to violence. It’s simply because the system has this way of shunting the problematic layer into these cages. And that system works for most people, and remains invisible to them.

RS: When the “legal,” “moral” ways of gaining capital are not available to you of course you resort to other methods.

RK: Right, but it is more complicated than that. People aren’t just stealing food because they’re hungry. The question really seems to be about harm and why people commit acts of harm. But if you grow up in an environment where you are exposed to a lot of trauma, then I don’t think you can adopt an image of yourself as being of delicate value. And if a person doesn’t consider themselves to be worth very much, then other people aren’t worth very much either. People are worth such different amounts in our society. Even our bodies, when you think about a middle-class body, and how nurtured it is.

RS: In the chapter focused on Kurt Kennedy, Romy’s stalker, you have this phrase: “He needed certain things to feel okay.” That got me thinking about what men take from women, and on a larger scale, what any people take from each other, in the service of making themselves feel better, and how that ends up being exploitation. How do you think people can train themselves out of the habit of justifying exploiting others in the service of making themselves feel personal comfort?

Most people actually did the shit they got convicted of, and I still think that they need to have the chance to be rehabilitated and live in society.

RK: I think that love is actually quite selfish. I don’t know if asking people to temper their infatuation with empathy is a realistic call to action. I’m a child of the 20th century, I’ve read a lot of Freud, and Lacan, and then Melanie Klein, and I don’t really think love is about empathy. And when Kurt says that, I felt like I was actually exhibiting my own empathy for him. Which is that he is not… I wish I could avoid the silence, but he’s not stalking Romy in order to terrorize or harm her. He’s doing it because he thinks that that’s what he needs to do in order to get what he needs.

When I was thinking about the character before I wrote his chapter, just really when I decided to put him in the book, it was because I saw from the stalker’s point of view for the first time. I can speak to that experience from the other side of it and it is not fun at all. But when I saw from his side of it, I wanted to have his story told from his perspective.

RS: I find in the leftist circles that I run in that there’s often this focus on large scale data while neglecting the specifics in terms of marginalized lives. How were you able to circumvent that, to really focus on the specifics, instead of the large theories and data throughout the course of the novel?

RK: That is a great question. I think I know what you mean, where it’s just that the emphasis is on structural issues. And it’s sensitive territory in a way, because focusing on the individual story is such a part of the liberal fantasy of our “broken system.” Which is not really that broken, it’s functioning how it’s supposed to. And the danger in focusing on the individual story is because the number of people in prison suggests that we’re not going to get people out by appealing to the population on a case by case basis. That’s partly why I didn’t want my character to be innocent for the reader. Everybody wants to do that. The Innocence Project, looking to find people who were falsely accused, that’s serious, and there are good people who were falsely accused, of course, but most people actually did the shit they got convicted of, and I still think that they need to have the chance to be rehabilitated and come back and contribute to and live in society.

I think that one thing, in the way that I live my life, as I said, I’m a one-man experiment of a certain type of activism which is really like a buddy system. Where I have middle-class resources and I have friends who have none of that who are out of prison and they can call me and I’ll help them with stuff, or give them money, or just be part of a safety net to try to help them stay out of prison.

What if more people did that? And it’s not a solution, but it is an individual case-by-case orientation that I can defend the logic of. Sometimes people have said to me, “Wouldn’t it be better to use your standing and ability to speak to a much larger public, to write theoretical or opinion pieces, rather than spending your time bringing groceries to people on Skid Row?” But I try to do both. And in terms of the book, you know, novels really are organized around the trajectories of a few characters. I’m a student of Dostoyevsky and a believer in the idea that one character can become a conduit through which a history can flow.