Lit Mags

“Ram” by Swati Pandey

A story about aging away from home

AN INTRODUCTION BY HALIMAH MARCUS

This week’s issue presents the second of two related stories: “Youth” and “Ram” by Swati Pandey. While both stories stand alone, if you have not yet read, “Youth,” published last week, I encourage you to do so before reading on.

Both stories concern Ram, a once and future husband, math teacher, and father, at opposite ends of his life. While each of these stories is powerful in its own right, their juxtaposition makes that power even more deeply felt. Last week, in “Youth,” we met Ram on his way, by carriage, from one Indian village to another to meet his bride for the first time. During his travels, he anticipates his first sexual experience while reflecting on, and saying goodbye to, his childhood. But what happens along the road does more to usher him into manhood than what will happen in his marital bed. His marriage is arranged, the carriage borrowed. It’s a transactional pattern, in which the traded is indistinguishable from the trader, that will be define his future. As this knowledge creeps in, something else — call it youth — seeps out.

Even if we don’t forgive him, because we know where he has come from — physically, psychologically, and emotionally — we understand.

“Ram” finds the title character near the end of this life, living with his son in America. The wife he was traveling to meet has died, as has one of their sons. With little else to do, Ram roams the suburban neighborhood, counting his steps into the hundreds of thousands. His ascetic existence is interrupted when a neighbor falls in step, offering small talk and breezy friendship, a kindness Ram had not realized he craved, but is ill-equipped to receive.

These stories also mark Ram’s first and final experiences with women. From the memories of a teasing childhood friend in “Youth,” to the brief friendship in “Ram,” Pandey manages to depict an entire trajectory of sexuality and many of the attendant misunderstandings, humiliations, and violations. In “Ram,” we see a man who has lost what he was only beginning to lose in “Youth”; a man who has become bitter, misguided, and uncompassionate. As an old man, Ram behaves badly. And yet, even if we don’t forgive him, because we know where he has come from — physically, psychologically, and emotionally — we understand. Swati Pandey’s achievement makes clear that her talents extend beyond her ability to craft sentences, to curiosity that gives way to understanding: her empathy is hard earned.

Halimah Marcus

Editor in Chief, Recommended Reading

“Ram” by Swati Pandey

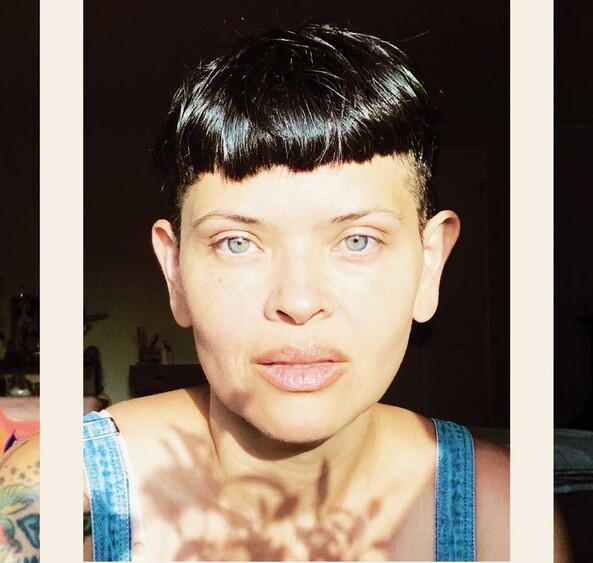

Swati Pandey

Share article

Every morning I walked four miles and counted my footsteps in my sandals. It was one hundred and fifty steps to the end of my street, another nine hundred after turning right, and some six thousand down a larger road until this village became the next, according to a green reflective welcome sign announcing the elevation, 1,300, and the population, 7,000, written in bold white numerals and likely not including people like me, immigrants.

At the sign I turned around, reversed my steps home, and wondered how the town I never entered had such a round number for its population when it had no way to adjust the total, unlike I who could shorten or lengthen my steps to reach a particular number, which I did for the pleasure of it. Maybe life in that place was such that its residents were born and died with perfect symmetry, to suffocate grief with joy, and joy with grief. Such symmetry did not exist in my home country. In India death was jagged and everywhere, like scrap metal.

For eight years, since 1982, I had lived in my son’s home in a small village in this new country, America. My son hated when I called it a village, but that was what it was, a village. Everyone knew everyone, at least the whites, and everyone said hello to everyone, at least the whites. Those who walked eyed me carefully every morning because I was foreign. They were people who had cars but chose to walk, and they had never known any other way of life.

“If it is a village,” my son liked to say sometimes at dinner with his mischievous grin, “show me the cows.”

“Not every village has cows,” I said.

“Only the rich ones?” He laughed as if he had never heard himself say it. Being the youngest son had made him childish long past the age for it. The quality seemed to charm his wife and daughter, at least, who indulged the old joke. They were always ready to laugh, a quality I found unsettling.

“Do you know,” my son turned to his daughter, “that your grandfather lived in a village very far away, on the other side of the Earth, and built his own house with his bare hands and with very little money?”

She did know because he had said it before, but she pretended not to know, or perhaps she did not remember. She was only eight years old so it was possible she had no interest in remembering facts about the elderly. It was true I built my home but so did many others then. Because we had to live in what we built our houses were small and careful, not like my son’s home, with weak wood walls and too many windows. He liked to count the money I never had when he was young because it made him prouder of what he had accomplished. He was an engineer, aerospace. His brother was a doctor in our home country. I had been a math teacher, not a very lucrative profession but one respected by all, except, I often suspected, my wife.

“Is it true baba?” the child asked. She rubbed my oversized knuckles. Her soft touch still made me wince.

“Yes, yes, it is true. With these hands.” I held them up and hoped she believed me. To me they were indeed the same hands that built a home. I had to squint, and remember the current year, to see them as they were now, gnarled and spotted like banyan tree roots.

“Wow,” she said.

“Yes, wow,” I repeated. It was one good thing the English had invented, the word wow.

“We had the four of us in one bedroom, though sometimes it felt like five people, it was so crowded,” my son said.

“And more wow,” I said, “many people when building a home, if they made a mistake, had their hands cut straight off.”

I made a chopping motion and landed on her wrist as I had many times before to make her giggle and worry at the same time.

“Dangerous work,” I said. “Hard work. This, your baba did. And still I have my hands.”

“Is that why you have this scar?” she rubbed an old wound with her little thumb.

“Yes,” I said. “Yes, an accident. Accidents do happen.”

“All right, you have said enough,” my son’s wife said, worrying about the child’s fears.

“I’m fine,” the girl said. Another wonderful local expression. To grow up in an American village, I thought every time I looked at her, is to always be fine.

After dinner, I did one more walk in my son’s front hallway, lined with pictures of the girl growing older, up and down thirty times, fifteen steps each direction. My granddaughter learned to count this way, walking with me in the hallway after dinner, though she otherwise learns not from me but from her television.

Counting made it easy to forget what you were doing especially if you had to count as high as I did. And even at my advanced age, it had become too easy to count to thirteen thousand and two hundred in this language. So I stopped starting from zero, and instead counted the steps of a week or a month or a pair of sandals, which gave me the added challenge of remembering numbers from the day or the walk before, not just the moment before. I counted the bites of food I ate and how many times I chewed. I counted until I fell asleep each night. I counted the number of minutes the girl watched television and the number of times her mother stirred a pot of lentils even though there was no need to stir, the pots here did not burn. Counting was simple, grim, bound by clear rules. This was how I filled my mind until I met Patty.

“Patty, like a hamburger?” I said.

“Well, no, silly, it’s short for Patricia.”

At least this silliness made her laugh. Patty or Patricia told me most of what there was to learn about her the first day we met, even though she only walked with me from step one hundred and eighty-five until step twenty-five hundred and thirty-one, less than two kilometers. It was difficult to count with her next to me, talking. She was a tall blond American, and the only person who had ever said more than hello to me during my walks. We met as we turned together from my son’s street — she must have lived on the opposite side — to the intersecting road. She waved at me with a long and excited arm as if I were an old friend. For a moment, I wished that we were old friends, wished that it were even possible, that we were not divided by decades and a hemisphere, for the pleasure of having met her when I was young.

“I live in a little house just down the road,” she said. “My husband passed so it’s me and my boy Milton, my sweet problem child. He is eighteen and has absolutely no inclination to get a job or a girlfriend or anything. If I ever dare have a date, which is near impossible in this little town because all the men are either married or too young or dead, my Milton goes wild with envy and slams all the doors he can think to open and when he is not slamming doors the boy’s poor eyeballs are just glued to the television screen. I leave to take the bus to the hospital — I am a nurse for gentlemen and women much older than you — and eight or twelve hours later depending on the day, I come back and there he remains, without having moved an inch, except maybe for school but I don’t even know for sure that he goes, the poor boy.”

The conversation about this Milton brought us from the corner of my son’s street and the road intersecting it to very near the large crosstown way.

“And you? What is your story? What brings you to our lovely little town?” she asked.

“My story,” I said.

“Yes. All about you.”

“There is no story. I am here living with my son and his wife and daughter. My other son lives in my home country, India. My own wife is gone for many years now,” I said.

“I am so sorry to hear that, how terrible,” she said.

“Oh, it is quite all right,” I said. “Now she is, I suppose, at rest, as you say. What is it? Rest in peace? Life was hard for her.”

“Hard enough that she would prefer to be dead?”

I stared at her, stunned at the shameless question. This Patty had no right to speak as she wished and yet she must have believed she did. Americans and their freedom of speech. It turned them all to idiots. But it was then I noticed her eyes, like lapis set in ivory. I had never had the opportunity to peer at such length into blue eyes. She looked the way Americans like to depict angels, white, pink, blonde and blue.

“So why did you leave?” Patty said, looking away from my gaze. “Was it because she passed on?”

“It was not that. I went on living there for some time. But when I retired from teaching mathematics I thought I would spend some time here with my youngest son,” I said. It was a lie. My other son had kept me at his home, had grown tired of me, and had decided it was my younger son’s turn even if it required me to move here, even though I had no desire to die in this country in one of its perfect hospitals, even if it came with a Patty. I wondered how many men had expired with Patty at their sides.

“That was a very efficient telling, I’m sure,” she said.

“Do you walk each morning?” I asked in an effort to talk about something more appropriate.

“Well ordinarily I sneak out very early before Milton wakes up so I can make him breakfast when I come back, but the boy sleeps later and later. In any case, no, I haven’t walked for very long. There are things I used to do in the morning like garden and jog and play tennis but these things grow difficult for old knees don’t they?”

“Your knees don’t seem very old,” I said. They were in jean shorts, pale white, with a few blond hairs on the dimpled caps. Their slight fat made the knees appear to smile.

She laughed, showing all her strong white teeth, and only then did I realize I had said something I should not have said.

“Well don’t frown like that,” she said. “It’s just fine to ask, I’m not one of those sensitive women. I am forty-five. But my knees are ninety.”

“I am seventy,” I said, smiling with no teeth, as I preferred. I worried that sweat might start rolling down my bald head. She was only forty-five. Something had aged her face beyond that, but she was still beautiful. She had pink lipstick but nothing else on her face, and it made her blue veins appear bluer under her pale skin.

“Seventy, well isn’t that something,” she said.

“Is it something?” I rubbed my old gray chin. It was sharp once, indeed, before my skin went so slack.

“You don’t seem that age is all,” she said.

“Seventy years young, yes?” I said. “That is what they say, Americans?”

“Isn’t that the truth? Years young. You see actual young people like my boy and they act like they’re older than we are. They don’t walk or even move much. I think the last time Milton really moved was when some toast I was making got caught in the coils and lit on fire and the smoke alarm was blaring — woo-oooo, woo-oooo, woo-oooo — and that boy ran faster than I’d ever seen, whoosh, out the door in his boxers. I think he ran further than you or I have ever walked on our morning walks. He has always been scared of things, well, for all his years.”

I smiled at the sidewalk and wondered when was the last time I had run for any reason. I could not recall.

“I walk four miles a day, at the least,” I said.

“Four miles all alone? My goodness. With no walking shoes just those old sandals?”

“Yes,” I said. I hadn’t realized my sandals were old. They had not yet traveled even three hundred thousand steps. “It is no problem. In my country I had no car and in fact never rode in one until I came from the airport to my son’s home.”

“Goodness,” she said.

“Yes,” I said. “So I walk everywhere and I count my steps when I walk. But today, I have not counted.”

“Because Chatty Cathy here won’t quit.”

“Who is Cathy?”

She laughed in her loud way again and raised an arm to wipe sweat from her hairline, careless of showing me her underarms yellowing her white sleeveless shirt. There was not a single stub of hair that I could see, just rosy whiteness.

“It’s an expression,” she said. “Listen I gotta get back to my boy and I sure can’t keep up with you. Are you really seventy?”

“My knees are thirty-five,” I said.

“Well of course they are,” she said through her thrilling laugh.

In the evening I asked my son and his wife at dinner if they knew a woman Patty or Patricia with son Milton. The wife thought she knew maybe a Sally and a Pauline but no Patty. My son knew only the neighbors on the two sides of his house because those were the ones he saw getting into their cars for work each morning and with whom he had to have negotiations about fencing. My granddaughter knew only the parents of her friends.

“Madhu and Raj are Sunita’s mom and dad,” she said. “Justin has no dad but he does have a mom but I don’t know her name. Jackie has a dad George and her mom is Melanie. Jackie’s real name is Jacqueline but she goes by Jackie because shorter names are cooler.”

“Yes,” I said. “This is why Patricia goes by Patty. But sometimes she calls herself Chatty Cathy.”

“You seem to know her quite well,” my son said.

“But none of you knows Patty. How is it so? She lives across the road here,” I said.

“I told you it is no village,” my son said. “We only know the neighbors and the people like us, the foreigners.”

My son scowled, an ugly expression I never managed to force off his face when he was a boy.

“I know people,” the daughter said.

“Quiet, child,” the wife said. “Let them talk.”

“Where did you meet this Miss Patty?” my son said.

“Right here on the road. She is walking like me,” I said. “She lives alone with her son.”

“No husband?” my son said.

“It’s always good to have friends,” the wife said. “I know, it took me years to find them in this place.”

“Friends are not family,” my son said. Since taking me into his home, he enjoyed discussing the importance of family, though when he was growing up, all he wanted was to leave us, and he did. “Family is why we are here. What have friends done for you?”

“They have been with me when you are at work all day and night,” his wife said. “They talk to me when all you do is sit before the television.”

“We are not friends. She is just a woman,” I said.

“Just a woman,” my son said. “There is no such creature.”

“Ch-ch-ch,” said his wife. It was her timid way of signaling dismay.

“I don’t think he should — ” my son said.

“It’s fine,” she said. “He needs more to do than watch her.”

“I don’t need anyone to watch me,” the girl said. “I’m eight years old.”

“You do need someone, child,” his wife said. “This is why your baba is here. So you can spend time together.”

I said nothing and continued to eat. Whenever they talked of spending time with me it sounded like talk of a boring family vacation — only pleasing for its impermanence. After counting the last of my mouthfuls, I stood to walk. The girl joined me, as she sometimes still did, keeping count. I put a hand on her head as we walked. She had several adults who might watch her, neighbors and friends of the wife, official hired helpers, the school itself. But instead I watched her. Everyone seemed to believe that I needed an occupation, even if that occupation was tending to a small child, like a woman, to ease into my dotage. They seemed not to notice that I was active, awake to the world, gifted with good eyes and ears and young knees.

The girl walked home from school every day with that backpack nearly the size of her entire body, filled with the fat textbooks that children here use. Although the girl and I did not speak very much beyond hellos and a story here or there, I was watchful and restless until she arrived from school and when she did, I sliced a green apple and salted it for her and went to take a nap until dinner. For a time I tried to help her with schoolwork, but for some reason, she found me unhelpful, or perhaps unkind. It surprised me how little a child of her age knew of math. Between the end of my morning walk and her arrival from school, there was very little to do but read my old prayer books, repair their brown paper covers, or sleep.

It would be a lie to say I did not think of Patty instead of falling asleep to numbers that night, my downward count, as I usually did. Chatty Cathy. That was a hard thing to say for me. The hard T sound and those sharp As were unfamiliar to my tongue. Chatty Cathy, I practiced, whispering into the dark below the speeding ceiling fan. My son chose not to use the air conditioning. To save energy, he said, but really he wanted to save money.

Patty. Patricia. Twenty-three hundred forty-six steps, a wonderful number, we took together. A woman like her should have many friends. I wondered why she was alone and why she would decide to talk to me.

The following morning I walked the one hundred and fifty steps until the end of my son’s street and then crossed the road, thirty new steps, instead of turning. Nearly twenty-four hours had passed since Patty, or some fifteen hundred minutes. I was not counting. It was only an approximation.

There were other directions to walk though most looked the same as the rest, trees rooted every ten feet along the smooth white sidewalks that rarely carried litter of any kind, or even an ant. I preferred the large roadway, slightly dirtier, with the cars flying past. It gave me a sense of life.

The houses on the other side of the road were exactly like the houses on my son’s side of the road except smaller, with no second floor. But like my son’s side, this block had what my son told me was called tract housing, in which every third or fourth house was the same but the families in each put up small markers of difference like a hoop and board for basketball or a rose garden. There were many of what my son called “lawn ornaments” even though they were not ornamental at all but rather like children’s toys, plastic and garish. My son himself had only one ornament, a small American flag planted in the ground, as if his quarter-acre of land were a colonial outpost and he the administrator.

I tried to occupy myself until the emergence of Patty from one of the houses, though I could not anticipate which one, could not know even whether she would walk today. It was the correct hour for her to begin her walk if she was precise, as I was, about when to walk and when to return home. But time must have been different for her. I walked around the block, counting the houses, fifteen, then the cars, thirty-seven including five vans and three trucks, then the ornaments, fifty-two, because one house had forty-one alone, those long pink birds. I made another round, moving newspapers from driveways to front steps. I wondered if the families inside these houses could see me, and whether I alarmed them. I was old now, however, and probably not alarming to anyone. I had passed to the stage of being a nuisance at worst, even though I could still shout with a bull’s voice and throw my fist at a nose. I believed I could, in any case.

“Hello my new friend, are you waiting for me?” She was standing across the street. I could not tell from which house she had come. “Well, I overslept right through my alarm and the snooze. And really, what are you doing with those newspapers? That is so sweet of you to bring them in.”

“Good morning Patty,” I said.

“Good morning yourself and please forgive me but I have forgotten your name,” she said. “My mind is aging fast, you know.”

“You may call me Ram,” I said. She misremembered. I had never given a woman my first name, not once in my life.

“How do you spell that, R-A-H-M, like the Jewish name?”

“R-A-M but sounds like Rahm.”

“Well hello Ram. Now don’t you want to count this morning? Or can I walk with you?” She was already walking with me before she finished asking. She began to tell me about Milton having what she called a “meltdown” the night before. She refused to speak further about it, so I ignored it as well. I did not think she could manage silence about any subject, and I was correct. She began to tell me what happened.

“He wants to go driving across the country with his friend Luis in a big van that Luis bought for eight hundred dollars off some addict who lives on the far side of our big highway, the one south by a mile or two of here. And I know that boy is an addict because I know what that looks like from my work as a nurse and I just don’t know why Luis or any decent person would give a poor boy like that any money because you know where it’s going. So I said, no, Milton, you may not go riding across this beautiful country of ours in that hunk of junk — which by the way is now in my driveway — no matter that I did it when I was a young woman. But that was with my husband in a good car, a Camaro, and we were honeymooning.”

“Honeymooning,” I repeated. It was one of the top words in the English language by my estimation. Hunk of junk was also good. I wondered what a Camaro was.

“Yes, I know, not very romantic but my husband wanted to see the country and I went along with him, story of my life,” she said. “So Milton explodes, punches a hole right through my new white cabinets and slams the front door so hard that the house shakes right down to its foundation. So he went off who knows where to do who knows what and came back lord knows when at night. So you see, Ram, I have not slept a wink, I was so worried about that poor boy and I was so certain that he had just up and left in that likely stolen vehicle that will break down the moment they hit desert or a mountain road and then what’ll they do? But he came back at least, for now. That’s the type of boy he is, Ram, he’s not as bad as his friends and he does need me.”

“My son is good except for silly jokes he likes to make,” I said. “He had a brother who was perhaps more like Milton. A boy who did as he pleased, even when he should have obeyed. But he died very young.”

“Oh no. How?” she said. Her round face was gentler when she was sad. All of her skin appeared to droop at once.

“Disease,” I said.

“Oh, how awful. Cancer? Childhood cancer is just a terrible thing. It’s why I can’t stand to work in the pediatric ward.”

“Malaria,” I said. The shame that it was malaria felt almost as grave as the disease itself. “It was not deserved.”

“It never is, I should know,” she said. “Good gracious.”

I was not sure why she should know, or what. She was so buoyant. A soap bubble of a person. The sun was hitting our shoulders hard, and hers were so red, I thought I could simply cover them with my arm, perhaps, and hold her. I could. I could. She would let me then, it only took the mention of the death of my son. My wife never loved me again after his death. Why shouldn’t I win another woman from it? Disgusting thoughts.

“In my country, in those days, the disease was very common, especially for children,” I said. “You feel the pain of loss, yes. But in the midst of so much loss, you realize how small your own is. You do not struggle. I still have two living children. And they live well. One here. One in my home country, which is not like it was when I was a man. It is safer. Cleaner. Stronger. Like a Western place almost.”

“That is really something Ram,” Patty said. “That is just not how people think here. People feel their suffering like they’re the only ones.”

She was crying suddenly. This was certainly the moment I could, even should, hold her.

“Oh I’m sorry,” Patty said. “It just makes me think of Tony. My husband.”

“How has he died?” I asked. Something was churning in me, the thought of my dead son, my dead wife, and now this dead man, encroaching on my continuing life. Seventy, and unlike him, I would make seventy-one, would I not?

“A car accident,” she said. “Ages ago. Years and years. In the middle of the night. Slammed right into one of these stupid trees on our sidewalks.”

I did not know what to say, so I said, “My wife never cried in front of me, even when our son died. She simply went on living.”

“She must have been quite a woman,” she said, I hoped with envy.

“Yes, yes. She was strong,” I said. “She died of a cancer of the brain when my American son, his name is Nikhil, was the same age as Milton. Nikhil was always weak. Born weak, and his mother coddled him and loved only him. The love she had for me, for her older son, for her dead son — it all went to Nikhil and spoiled him. I think the reason he keeps me in his home, other than that it is required of him, is to be close to her again.”

“You’re here because he loves you,” she said.

I smiled. Americans loved love and hated the things that were actually meaningful, like duty.

“He keeps me because he must,” I said. “Everyone wishes I had died long ago.”

“Oh, hush,” she said, attempting a return to her usual gaiety. “You simply must be glad to be alive on this beautiful sunny day. Right? Otherwise you would be holed up in the dark, like my Milton.”

I waited for the child with particular restlessness that afternoon. There were things I said to Patty that I had never said to anyone. It was like what happens in a movie for a man and a woman, they talk to excess and somehow they become close and happy, except for me it felt painful, like a bloodletting. When a child dies he should stay dead. But after I mentioned him to Patty once, there he was, alive again. I could summon from memory, still: his date of birth, his birth weight — four-point-three kilos, strong from birth, my son — his date of death, his age upon death, nineteen hundred and seventy days. He had little time to become more than the sum of these figures. And my living others never seemed enough. My youngest son, the American, bore most of the weight of his absence. The punishments that I otherwise would have divided between two misbehaving bodies were his alone.

When my granddaughter arrived I had reason to put away my old thoughts. I handed the girl her salted sliced apple and sat down next to her. She stopped eating and stared at me.

“You can have your nap time now,” she said, as if she were the one babysitting me.

“I will sleep soon,” I said. “First I will sit with you.”

“Okay,” she said.

“Okay,” I repeated in her intonation. She smiled.

“Baba?” she said. I didn’t like when she asked one-word questions, but I did not correct her.

“What is it, child?”

“Are you friends with that lady? You know, Miss Patty?”

“Why do you ask?” I said. My loose skin was still capable of tightening across my chest.

“Mom and Dad were talking about it.”

“Oh? And? What were they saying?” I wanted to appear simply curious rather than anxious to know. I smiled and put my hand on her black hair still hot from the sun. I took her final slice of apple and she glared at me.

“That was mine,” she said.

“I’m hungry too,” I said.

“So get your own,”

She was not supposed to talk back or start sentences with a so. None of my children, living or dead, had so many demands, and such comfort with plenty.

“Well? What were they talking about Patty? ” I asked.

She forgot about the apple. “I don’t think I’m supposed to say,” she said but continued anyway. “Mom thinks it’s cute.”

“Oh?” I felt the heat of shame The idea that I could be called the same word as this little girl. It was a failure of the language and more so of manners.

“Mm-hmm,” she said. “And I think it’s cool you have a friend.”

“Yes, yes,” I said. “And what does your father think?”

The girl shook her head.

“I’ll give you the answers on your math homework,” I said. I felt hotter by the minute from shame.

“Really?”

“Yes, really, now speak.”

“He says everyone will laugh at you,” she said. “Because you’re old? And she’s young and she’s from here and you’re not. He says there are rules.”

“Well I am too old for rules,” I said.

“Baba, you’re never too old for rules.”

“This is a free country, that is what your dad is always saying,” I said.

“There’s one more thing,” she said. She leaned in closer to me and put one small hand on my arm, as if protecting me from something. “Dad says her husband died drunk driving and that’s really sad. You’re not supposed to drink and drive.”

“All right, that’s enough,” I said. That Patty, so happy, so light, had experienced such tragedy seemed impossible, but could a child invent adult tragedy? I regretted that she spoke of Patty at all, and that her mother did too, her mother who would have had no marriage were it not for me allowing her to marry my son. I regretted still more my desperate urge to know.

“You’re the one who asked,” she said, as if she knew what I was thinking. Already a woman, this child. She pulled a piece of paper from her backpack. It was ten problems involving adding simple fractions. I could finish it in a minute or less, of course.

“And? What do you say?” I said.

“Thanks, Baba,” she said, and went to turn on the television. Her face slackened happily at the sight of the cartoon ducks she loved. I did the math in telltale pen because I was angry at her satisfied look. If the teacher questioned who did her homework, she would be in deserved trouble.

The next morning I walked to Patty’s block again, five minutes later than the prior morning, so I had time only to move a few newspapers to doorsteps before she emerged from the home, the one with the dingiest of vans in the driveway. Her home was a dusty blue single-story with white trim with two flags — one American and one flowered, for no country. There was a wild bush of pink flowers, a row of violets, a swinging bench with yellow seat cushions, and an old basketball hoop over the garage door. I let myself imagine it said something about her, as was the intent of these American gestures.

“Hello Ram!” she said. “Milton has come to meet you.”

I could barely see him even as I crossed the street to her. He stood in the safe darkness of the front entry, dressed in black, blond hair covering his eyes. I did not want to shake his hand but that was what she seemed to expect. I thrust my arm from the heat of the front step into the air-conditioned space he occupied. His hands were cold and damp.

“Hey man,” he said, shaking hair from his eyes. They were a paler blue than Patty’s, and I realized he must take after the dead husband. In that moment I managed to envy both men, however stupid a feeling it was. “Thanks for hanging out with my mom.”

“It is no need for thanks,” I said. Even if Patty had told him to say it, he seemed sincere. They must have reached some agreement over the desired car trip.

“Ram, I’d like to take you on a new walk. I have my good shoes on,” she gestured to gleaming white walking shoes, “and I’m ready. There actually are hidden little places in this town, trails lined with old trees and crawling vines. It’s why I came here and not the next town or the next one because otherwise, what’s the difference? I don’t know how much traveling you have done in this county but I can save you the trouble because it’s all the same, except for this town and its little trails for walking, which you like so very much.”

“It is a time-pass,” I said. We waved goodbye to Milton and began.

“Pastime, you mean?”

I shook my head. “I know this word. A pastime is something to enjoy. A time-pass is something you do because there is nothing else to do.”

“Well you sure know how to flatter a girl,” she said, laughing.

I reddened and stayed silent for some time. There was likely something an American man would know to do or say, but I did not know it. I felt my skin tighten again. It was not nerves. It was something for her.

Within four thousand northward steps we turned onto a dirt path that was, as Patty promised, lacking the precision of the sidewalks. In the patched dark beneath the leafy trees, my head stopped burning from sun, and no sweat dripped down my sides. Patty’s skin revealed its pinkness in that light. She was wearing a sleeveless shirt again, through which I could see a white undergarment. Women’s things were always lying around my son’s house, or drying on lines in the yard where his wife hung them, so I was somewhat accustomed to the sight of them, though not on a body, not for some time. I stared at my feet to have something else to look at and counted steps while Patty spoke of various uninteresting things, the history of the town and its trails, until she came back to her constant subject.

“I thought Milton could learn to like fresh air on these trails, especially after his father died, a boy needs nature, activity, something to help him grow up,” she said. “For a while he had a job and helped me with our finances, which are not in the best shape since Tony died, or even before that, since he lost his job, but just when I thought Milton was getting grown and right and happy again he turned into who he is today.”

“What happened to him?” I asked.

“Oh, I don’t know. Adolescence.” Her voice had a hard edge that I had not heard in it before.

“And what is it that happened to your husband? I have forgotten,” I said, though of course she had never told me what caused the accident. I did not want to be the only one of us airing old sorrow. I was still looking at my sandals and counting steps but I could feel her staring at me and then finally her soft hand on my shoulder, turning me to face her. It was the first time she had ever touched me, and I wished it were a kinder touch.

“What have you heard?” she said. Her voice had a new quality that I didn’t like in her, the whimpering rage of a wounded little animal. It was enough to confirm the girl’s story.

“I should not have asked. Please forgive me, Patty,” I said.

“He was drinking,” she said. “I couldn’t stop him.”

It was the shortest story she had ever told me. I tried to create the look of sympathy on my face that she could summon so easily. But I had difficulty finding a feeling for this husband, especially because of the alcohol. In my country we did not ask for sorrows. We had enough given to us.

“I am sorry, Patty,” I said. Americans always expect this word, sorry. What kind of culture makes a casual and common word for this feeling?

“You’re lucky. I would go through it all again if Tony could just die of malaria, anything where you get to say goodbye.”

“Malaria is not an easy death, Patty,” I said. “To watch life slowly leave a body is a hideous thing.”

“You’re right, you’re right,” she said. “And of course there’s no malaria here. It’s a pity. If your son had been born here, he would still be alive.”

“Patty.” Her refusal to move her eyes from my face was unnerving, and I felt an old and electrifying rage. Women were not supposed to stare at men. Women were not supposed to pity the dead sons of men they barely knew. But why would buoyant American Patty know that or have any respect for me or for my past? Here she was, begging me, daring me to say and do something to her.

I thought suddenly of my wife, pleading through her strong gritting teeth for me to lie with her on her deathbed, her eyes locked on mine like Patty’s were now, with that womanly animal look. I refused my wife quietly and sternly. The doctor nodded his approval. The nurse turned her back and her shoulders shook. The other patients in the long ward carried on with their separate miseries. How could I have embraced her? That would be a sign of my own weakness. I had to let her scream alone.

“Patty,” I said. I put my arms on her shoulders. She was hot below my hands. I could feel the thick straps of her undergarment beneath her flimsy white shirt. She was crying now, her tears mixing with her sweat. I imagined their salt taste. I wished, briefly, that we had simply walked along the highway, hands clasped behind our backs, not touching, as usual. I did not know what to do with my hands here. They did not want to leave her body. She was closer and closer until our lips met. Hers felt sticky, like a pastry, and mine were paper dry. Then, her hands were on my chest.

This was what it was to be in America, I realized. I had known no woman but my wife in all my years, not even a village girl in my youth, though I tried with one, once, I even remember her name and her age. I tried and failed. But here in America there are willing women for old men and dark godless paths to take, to which the women will bring you, and a society that shrugs at everything because it has everything. I was right. There need not be rules in a place like this, not with a lonely woman like this, and here I had been simply whiling my last days quietly away, waiting for my death.

I pushed my lips hard onto hers, broke through the wall of her teeth with my tongue, pressed my fingers into her shoulders first and then underneath her clothes. Her hands had surprising strength against my body. The feeling of touching her went from my mouth to my heart; blood pumped hotly to every inch of my skin, and I thought I felt the old heat between my legs. My wife had been dead twenty years. The enormity of that span of time, without this, made me clutch Patty harder until I thought it time to push us both to the dirt, no matter my old knotted hands, my brittle body, it still had its power.

We were on the ground when I felt a prick. With sensation everywhere in my barely familiar body I could not tell where the pain was. It was a bug bite, a stone jutting from the earth, the pinch of guilt perhaps. No. I felt the pain spread. It was her teeth biting into my tongue. My mouth filled with the heavy iron taste of my blood. I realized her hands were not holding me — had not been holding me — but rather were pushing me away. I took my hands off her and rolled onto my back.

“This is disgusting,” she said. “You’re disgusting.”

She dared to run on her old knees, simply to be free of me. I lied on the shameful spot of dirt. When the sun began to arc down I finally stood again and walked home. It was useless to count. Nothing could move my mind from her.

I refused to walk from then onward. This caused a commotion with my son and his family. They spoke openly of my imminent death without asking why I suddenly spent my days shut in my room. I would not have told them, in any case. Instead I simply yelled at them to send me back home because I did not want to die in America.

“Here they will freeze me and put me in a box on a plane,” I said. “With crates of lawn ornaments and suitcases full of T-shirts.”

I saw the wife smother a laugh, which I did not think to be inappropriate. Death can be funny, particularly when belated and slow. But my son frowned, and my granddaughter avoided us all. Children know better than adults how to fear death.

“I will talk to my brother,” my son said. “We will find you a home.”

“You have been waiting to send me back at first possibility,” I said. “As if I am a defective shipment. Not your father.”

“You have just said you want to leave. You hate it here,” he said. “All you do is sleep and talk about how strange America is.”

“I have long known it, since the day I arrived. A strange and awful place pretending to be wonderful,” I said, the closest I came to saying anything at all about Patty. “I cannot die here.”

“That I do not control,” my son said. “Death comes everywhere.”

I cried when he said it, and my tears silenced everyone.

In bed for most of the hours of the day, I could feel my muscles slacken and my bones lock in place. I prayed for my mind to calm its hectic function. But staying in a room alone will tax any mind, old or young. I watched the fan make its circles and pretended I was a boy again, pulling a rope to make the fan sway for my parents because I was the youngest and that was my duty. We had no lights then, no water except from a far-off well. I lifted my old arm up in bed and made the same gesture, pull, pull, pull to make the fan move and I eventually convinced myself that the mechanism of this grand plastic American ceiling fan was the very same as the fan of my childhood. Let me breathe, I begged the fan, let me breathe the young air again.

But kinder thoughts like these were rare. My mind held steadfast to her, to Patty. A ridiculous, ridiculously named woman with an addict husband and surely an addict or miscreant son. She was the shameful one, not I. She was the one who should never have come here and never have spoken to me. I was an old man with no ill wishes or deeds in the world, ready for death. I burned the bodies of my son and my wife, watched them return to the elements, and kept in fair health despite my years and my means. She was the one who had lived a dishonorable life. She came to me. If she hadn’t come to me, I would simply have kept counting, up and up, every gesture, until my gestures grew fewer and fewer, my steps shortened and then stopped, my breath gone in one final guiltless exhalation.

Nights were unbearable. I woke up choking on my own sweat, or so it seemed. The heat made it feel like my home country, like my marriage bed but missing one body, the body I used so heavily from that first night onward, desperate to erase my youth and its unsuccessful seduction. My wife had her long thick hair, her beautiful walk, her perfect teeth. Did they bite like Patty’s? I do not recall. I only recall how they reminded me of a dead man’s bones, they were so white and thick below her pink gums. The gums blackened before she died. Yes, death was everywhere, as my son said.

My poor granddaughter was the only one who came to me during the night, when I cried. She slept in the room next to mine, our heads separated only by a thin wall through which she could hear everything, every wild word I mumbled in sleep, every confession, and of course, the sobs. She held my old hand until I quieted down, already possessed of the capacity all women have to care for a man no matter how terrible he is. As far as I could tell, she never told her parents about my crying. It wouldn’t have mattered. Part of aging, I supposed, was to become very intimate with humiliation.

On a rainy morning, because rain was rare, I found the strength to rise from bed. My bones creaked and I felt a slight pain in my temples. The staircase was difficult, but I managed it.

My son stopped eating and his eyes gaped. His wife raced to serve me orange juice and buttered toast. My granddaughter smiled and jumped up and down in her seat.

“Does this mean I don’t have to go to daycare?” she said.

“Your baba still needs rest. But we are so glad he is up. Aren’t we?” the wife said.

“I am going for a walk,” I said. I was desperate to see her. Patty. She would not walk in the rain. I could find her at home, with Milton. I could say I was sorry and then promise to never bother her again. This was all I wanted.

“You can’t walk. You haven’t stood up in weeks except to bathe. Sometimes not even then,” my son said.

“I am only walking a short way.”

“It is slippery,” the wife said.

“I can walk with him,” said the girl.

“You are not walking to that woman — ”

Before my son could finish speaking I pounded my fist on the table, upsetting my juice. The girl began to whimper.

“I am your father and as yet I am still alive,” I said. “And your mother is long dead. And I can do as I wish.”

“You,” he said, almost shaking with rage. “Your ignorance. First of her wishes, then of her pain. You think her headaches came for no reason? You ignored them for years.”

“You are the one who left her for this country. Is it any wonder she died so soon after?” I said, shocking even myself. I had never said such things.

“She died because you refused to help her,” my son was wailing now, my poor son.

“There was nothing I could do. And there is nothing I can do now,” I said as firmly as I could even though, for the first time in decades, his boyishness did not bother me but instead seemed sensible. It was a protest against me and my refusal to die.

“You will not go to that woman,” he said.

“Nothing I can do now, my son. She is dead,” I stood and attempted to kiss his head. He jerked away.

“Go,” he said. “And when you return, we will find a place for you in your country. You can die alone in a dirty hospital surrounded by misery. As she did.”

“Don’t speak to your father this way,” the wife said, stroking the crying child’s hair.

“It is all right,” I said. “It is deserved.”

There was silence. I put my dishes in the sink, which I had never done before because the wife always did it and which I hoped served as proof of my fitness of body and mind. I took the large black umbrella my son kept by the front door. It was only drizzling outside and I soon felt ridiculous carrying it. That feeling deepened when I found myself on Patty’s doorstep, heart madly trying to escape my chest. When I knocked, the door opened, but it wasn’t her.

“Hello, Milton,” I said.

“Oh, hey,” he said. He put his hand out dumbly. We had already shaken hands. I did not realize I would have to do it at every instance. The walk was indeed a terrible idea. My feet and knees ached. I needed to sit down.

“Is Patty here?” I said.

“Um, no,” he said. I couldn’t tell if he was lying because his hair was too long to see his eyes. He was perhaps fourteen centimeters taller than I was and he looked very young for his age.

“Can I come in?”

“Uh, sorry, man, I don’t think so.”

My stomach churned in horror. She must have told him what I did, or some version of it. Americans say whatever they want, even to children who have no business knowing what women endure. Inside, the house was entirely dark, save for a television screen on which two men were boxing. The camera focused on the blood each drew from the other’s teeth.

“I can wait for her?” I said, attempting to walk around him and trying not to think of the taste of blood in my own mouth weeks ago. “You need not be troubled. You continue to watch television.”

He stepped forward so that he filled the frame of the door. He crossed his arms. He looked unaccustomed to firmness.

“Sorry man,” he said. “Can’t.”

“Just a few moments with her?” I said.

“Look, I don’t care if you guys hang, even if you’re way older, whatever, right? It’s been ages since Dad and I’m sure you know what he was like in the end. It’s been like eight years, you know?”

I tried to smile. The young know nothing of time. He was a lot like her, to tell me something meaningful too soon. “Thank you,” I said, and added a lie. “She speaks well of you.”

He rolled his eyes. “Whatever. I just remind her of him. But I’m not like him. I’m not so bad.”

I smiled, and inched closer to the door. What did it mean to be not so bad to a boy like him? I could see the wallpaper behind him, pale green with yellow flowers, and the cold grey tile below his sock feet. There was an old photo of three blonds, all smiling in the way Americans do in photos, as if there was nothing grotesque about displaying a long gone moment of happiness.

“May I, perhaps, have a cup of tea? It is raining. I am cold, you know, my bones are quite — ” I said.

“Sorry. I was saying all that to say, you know, I get it, but she’s being how she is, so. You still can’t come in,” he said, shutting the door gently.

This was the story of the next several mornings, during which the rain did not cease, and my own son refused to speak to me, except to say the plans were almost done, that soon I would go.

I did not know exactly what I would say to Patty if ever she agreed to see me, but I continued knocking on her door, chatting briefly with Milton, and then heeding Milton’s request that I depart. Soon, I did not have to knock. Milton came to the door to pick up the newspaper, and usually I was already there with the paper in my hand. On a day of particularly terrible rain, I deliberately left my son’s umbrella at home so that I arrived at the door of Milton with old teeth clattering and woolen clothes soaked. The boy had some sense and let me inside.

“Jesus, man, fine, just stay to dry off but then you are gone,” he said. “And so am I.”

“You are traveling with your friend Luis?” Inside, the television was on, muted, and men were riding small motorbikes over hills of dirt.

“So she told you.” Milton left me in the front entryway with the old photo as if I too were an artifact. He moved jerkily, his body young but tortured, from darkened living room to kitchen, putting books and snacks into a large rucksack. He wrapped several small clear bottles, perhaps medicine, in socks, then transferred them to his bag. I sat on the sofa without being invited. It sunk beneath me like an old mattress. Next to it were stacks of newspapers, the ones I brought to the door each day, still unwrapped and unread.

“But Milton, it is dangerous,” I said. “The road. The old car.”

“Whatever man. She’s the one who freaks out about me driving since,” he said. “And listen, you gotta leave before she comes out here. She’s on edge lately.”

“On edge?” This was a new expression.

“She doesn’t say shit to me except when she’s begging me to stay or telling me how awful I am and how I’m just like dad.”

“Shit to you,” I said. The words were like mud in my mouth. I wondered if, to Patty, my shame was meaningless compared to any minor action of Milton’s.

“I’m out in like five minutes, dude,” he said. “Hope you’re dried off enough. Not like it matters I guess. It’s still raining.”

“Shame on you,” I said.

I heard him stop moving. He stood between me and the television. The room was dark except for that glow, silent except for the music called rock coming from somewhere. I stood up, the sofa squeaking to be free of me, and walked until I was just a few feet away from him.

“What did you say?” Milton said. This was a child who knew rage, clearly learned from his father. I could see it now, slowly replacing his pallor.

“She is alone. She is your mother. And you wish to leave her. Shame on you.” It was a phrase I learned from television. It was useful in America, where no one seemed ashamed inherently. You had to heap it on them, as you would a blessing.

“Shame on me? Oh you and she are perfect for each other,” he said. “You people can do no fucking wrong. But everyone else….”

“You can’t leave her. She needs you.”

“What, now you’re gonna try to stop me? Some fucking knight she found herself. A grandpa who can barely move.”

He finally looked directly at me when he said these words, and leaned closer to add a sense of threat. He held his arms too far from his body, like an ape. The impudence. My teeth hurt when I clenched my jaw but I kept it that way. The space behind my eyes was hot with quickened blood. I thought I tasted metal again. I would show him how to treat an elder. His own drunk father evidently never had. I curled my right hand into a fist as well as I could despite my knob knuckles and shot it toward his chin. The chin was too far away when I started, and further away it moved after I swung. My body followed my arm.

“Hey man, shit, relax.”

I heard him say it, and I saw him reach both ape arms toward my shoulders and hold them. He was steadying me. It was the cruelest thing he could have done. I jerked back, a mistake, the ground shifted so my feet were no longer planted and instead it was my head on something sharp, my back on the ground, my bones reminding me they were old by burning at the impact, cracking maybe, turning to dust, maybe. And then my heart, squeezing like a vise.

“Fuck. Fucking shit. Fuck.”

Blond hair hung above my eyes. I imagined it was Patty’s. But I saw Milton and his wet, frightened, pale little boy face. I saw the motorcycles rolling along, the muscled fans cheering, full of the happy stupidity of America, and I heard Milton say something about his dead father and now another dead guy not his fault, not his fault. But of whom was he speaking?

Where was Patty, I wondered? Where was she walking without me? And then, there she was, it was her hair I saw above me and her pale blue eyes. I murmured her name, or attempted it, I stroked her cheek, or attempted it. I waited for her embrace, waited with the sweet certainty that it would come. There was her ragged blond head above me and the hair shorter and finer than I remembered, the eyes paler blue, the face younger and like a boy’s.

But why was she crying? If it was for me, wasn’t it premature? Was I dying? The warmth was enveloping me. My head felt a kilometer deep and my feet felt as if they were walking on air. I counted the steps like I did down my son’s hallway, my sweet grandchild at my side, the wife nearby, my son nearby, but the steps and the numbers bled into one another. I asked Patty to hold me, begged her and begged her as my wife had begged me, and unlike my poor dead wife, I received it, the embrace, love. Oh, thank you, Patty, my American love, my only love, perhaps. And then the blond hair was gone and there were heavy running feet that were not mine, and then a motor. Above me I saw a ceiling fan swaying slowly as it used to do when I was a boy pulling a string to make it move, slow enough to count the turns so long as I could remember the numbers three, four, five, slow enough to seem lazy, as if slowed by the wet heat of that land, my home.