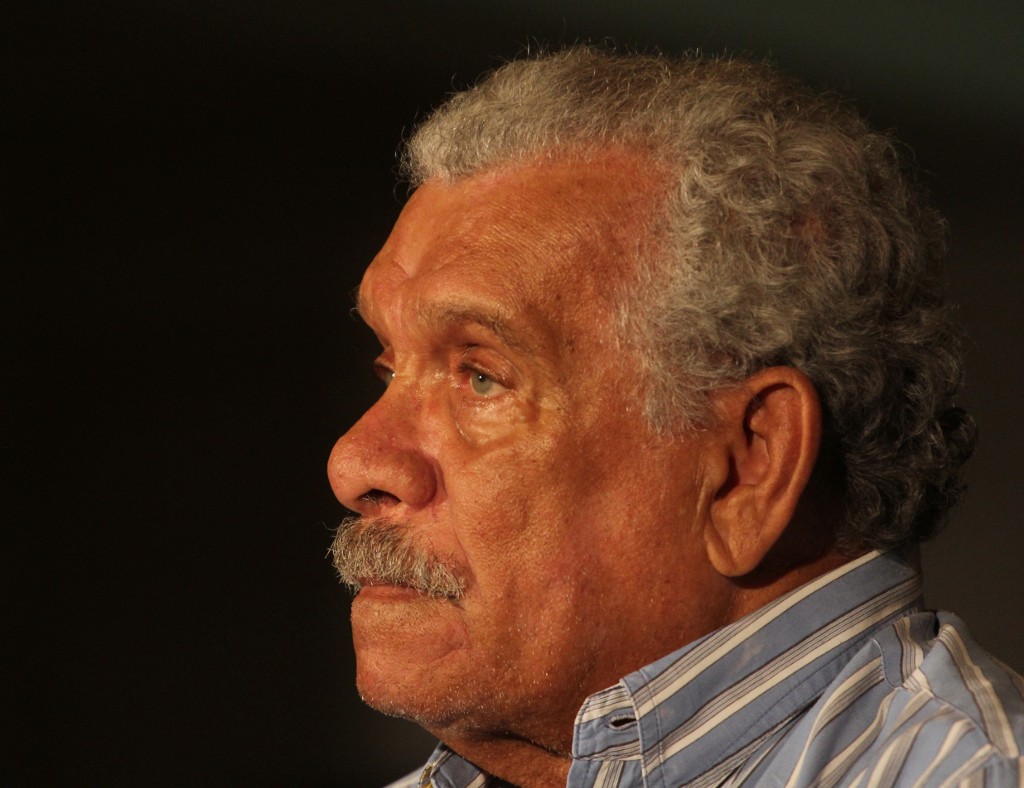

Interviews

Ramona Ausubel Writes About What Bodies Do in Secret

The author of the new collection ‘Awayland’ discusses how she explores feelings as form

Stop. Think. There must be a harder way.” So reads a letterpress sign that hangs in the kitchen of Ramona Ausubel’s mother, which the author recalled at the launch evening for her previous book, The Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty. The message resonates with much of Ausubel’s writing: it’s funny, but it captures something absolutely true about how most of us navigate life—specifically, about the ways women reckon with being lovers, mothers, and artists.

Such reckonings have proven to be Ausubel’s fiction sweet spot. Her 2013 story collection A Guide to Being Born (featuring the story “Tributaries” published in Recommended Reading), is organized by the stages of life but in reverse—in the end, the reader arrives at birth. And now, partnership and memory, pregnancy and motherhood drive the stories in Ausubel’s tapestried new collection, Awayland.

The author’s fascination with motherhood and all its phases and emotions could be understood as part of a larger exploration: to understand feelings by transforming them into things physical and bodily. The emotion that lends itself best to such transformation is the one with the most complexities: Love.

In Awayland, the 11 stories are grouped into four sections that cover several territories of love and anguish: yearning for a partner, perhaps for a child; allowing for distance in the pursuit of intimacy; waiting as an inevitable phase in every kind of relationship; and lastly, the dream of something that lasts forever. It takes a powerful imagination to realize these sensations as physicalities, but that is something Ausubel has in abundance. Loneliness is cast into a Cyclops creating a dating profile in “You Can Find Love Now”; separation is death at an all-inclusive resort in “Club Zeus,” or the lovers trading hands in “Remedy”; and in the penultimate story, mummified animals in an Egyptian museum manifest Till Death Do Us Part.

Awayland is a collection of many voyages and many lives. The stories take us around the world, and to whatever is beyond. Only a woman endlessly compassionate and curious could produce such fiction. That was exactly who I met when I talked to Ramona Ausubel. Somebody who took her feelings, and stopped, thought, and followed them a different way.

Lucie Shelly: A lot of your writing explores motherhood, but this collection has a particular focus on the precipice: pregnancy. To me, there’s a connection to be drawn between the gestation of a baby and the gestation of a story; I think it suggests something special about the woman as artist, she is a creator in both senses. Can you talk a little about your work’s focus on motherhood and pregnancy?

Ramona Ausubel: My writing does often come back to pregnancy, and I always think to myself, am I done with this topic? It is this fantastical thing that our bodies know how to do. I have two kids and I do not know how to grow a child. It’s not something that I understand, and yet my body knows this thing and can do it. Similarly, being a woman in the world, we’re asked to keep a lot of our lives under the surface. You have to be nice, you have to take care of everybody and do all this surface work, and everything else happens in the dark corners. With many of these stories, I was thinking about the way that art grows out of those dark corners. I have to write about that, I have to sink a bucket down into that dark well and figure out what’s been happening below the surface. There’s so much concealed and tangled and complicated. It’s just not what the world, in my everyday life, wants to hear from me. To me, art is the way that stuff can come up.

LS: Your first collection considers motherhood, too, but I believe you’d written it before your son was born. Writing this collection, having gone through two births and being a mother of two, did that change how you wrote about the experiences of being pregnant, raising a child?

RA: I feel like because I’m looking from the other side, I have a lot more information. These stories cast out beyond the surprise of “What?! You can grow a thing inside you?” With these stories, I knew what it was to then care for that creature, do all of the work to make that human survive and hopefully live happily. They also consider the many transformations that a woman will make in relation to her child, because the child will change, and she is required to change with it. It’s this tumbling wheel of constant change, and deformation and formation again.

LS: To me, there are cycles of deformation for both women and men, in bodies and character, in this collection. There’s a line in “Do Not Save the Ferocious, Save the Tender” that describes, “A body severed from itself.” We see bodies pulled into pieces in several stories, we’ve got the hands removed from the couple in “Remedy,” the fallen uterus of the aging woman in “High Desert,” ankles pop up throughout. I’m wondering what you were trying to explore by looking at the body in pieces rather than an inevitable whole.

RA: I’m fascinated by bodies and what we ask them to do, particularly what we ask them to do in secret — it goes back to that question of what we aren’t saying out loud and what we aren’t able to talk about. Those unsaid experiences, that all wind up in our bodies somewhere. So in my work, I try to turn the volume up on that a little so we can hear it more clearly.

With the couple in that story “Remedy,” the woman thinks she’s dying and it’s just not okay with her that she’s going to leave her beloved. It’s the beginning of their relationship and she knows they’re meant to be together, so she decides that she wants to try, surgically, switching hands so that they can be together forever. I didn’t intend it, but that story is the most autobiographical story in this collection. I remember so clearly when I was first with my husband and feeling that one lifetime was not enough. It was really upsetting to know we had this limited amount of time and one of us was going to die first. As a solution, I was thinking we’ll inhabit each other’s ghosts and that’s how we’ll handle that problem! The point is, that idea of limited time felt absolutely unacceptable to me, so I tried thinking through it in a bigger way: what if I took that real feeling and brought it to its maximum size — how could it physically express itself? And that’s always something that I’m coming back to. What happens if we put this feeling in the body and allow it to be as big physically as it is as a feeling?

It goes back to that question of what we aren’t saying out loud and what we aren’t able to talk about. Those unsaid experiences all wind up in our bodies somewhere.

LS: The couple in “Remedy” also seem totally happy in their own world, and I felt a lot of the couples in this collection exist in a separate realm or a liminal space. In “Mother Land,” the couple leaves California for the man’s far-flung family home in Africa; in “Heaven” we have a man and a spectral woman in some magical or spiritual place. When you write through and explore relationships, do you consider them as bubbles, at a remove from the world, or experiences that bring people closer to humanity?

RA: Totally both. We all have some kinds of relationships, whether that’s family or friendships or romantic relationships. We have these things that are one way on the surface, and a different way in private. There’s the official story, you chat to someone at a cocktail party and say, “Here’s who I’m married to and this is what he does.” But you never talk about the full strata going down the canyon wall of that relationship, and all of the things that relationship is about, has ever been about, and all of the things you hope or worry it will become about. It’s my instinct to move these couples around through space and time and say, “What does it feel like to be very, very far away and with only each other?” It’s another feeling that exists on the inside that I want to try and translate into some kind of physical realm.

The Rich are Different from You and Me

LS: Writers often talk about the limitations of language and words. I hear this nugget people drag out, that the Eskimo language has 32 words for love and English only has one. And that is an interesting difference, but I don’t think that if we had more words for love, and even if we didn’t use modifiers like “a mother’s love,” I don’t think we’d stop writing stories to expand that word and explore the feeling. Your interest in realizing feelings as physical experiences, for instance, is a very different method of understanding. But do you feel confined by language, or do you feel freed by it?

RA: I feel much more freed by it. I am a fiction writer, so I get as much invention as I want. And because my work has a lot of weirdness in it, I’ve created a pretty big territory for myself. That means I don’t require language only. I get to use language, but language is also the vehicle that enables a kind of magic trick: to take a small thing and make it big and see what it looks like. The language is my favorite part, it’s the most satisfying thing, and getting a precise image is the most gratifying part of the work. But language is also the outlet into a lot of other tools that I get to use. For the same reason, I don’t write nonfiction, though I’ve tried. There are some short essays that I enjoyed writing. But for me, writing longform nonfiction, language would not feel like enough; I wouldn’t be able to say, “We’re gonna cut our hands off and trade them,” because that’s not something you would do in nonfiction. So I see how language might not be quite enough, but for me it’s the clay that makes everything possible.

LS: I would say one of those other tools you use so well is humor. “Club Zeus” is a funny and poignant story about death, and the mother in it is comical but she’s key to the sense of loss. After sending her son to Turkey for the summer, the son tells us, “What she means is that I am on my own. What she means is that tragedy is also currency. That enlightenment depends on grief. That love grows in soil that has been tilled.” “Template” is also a comical story, but could be read as dark, maybe dystopian, with the idea of baby-making becoming a government directive. I’ve heard you say before that you don’t necessarily try to write funny, but it’s something that comes forth. Can you talk about using humor to access the layers of emotions and relationships?

RA: I love using humor when it’s right. It’s like adding salt to a food, it makes everything else that’s there feel stronger — especially something that’s in opposition to humor, so the darkness and the sadness. If you have something funny, it breaks a reader open and makes all of the sadness and darkness sort of flood into that space. You can get those moments of opening in different ways, but humor is one of them.

The tension between sadness and humor is really beautiful to me. “Template” started because I read an article about a real situation in which a mayor of a small town in Russia created a day off for couples to have sex. That really did happen, but I couldn’t find much follow up about it, so I had to imagine. At first I started writing it set in Russia, but I was like, I don’t know enough about Russia. So the question was, is there a place that’s so bleak that no one is even bothering to have children anymore? That people are really afraid to? So much that a mayor might decide, we’ve got to give them some kind of incentive — and that incentive might be giving them a day off to have sex. That felt like it could happen in any country.

The funny part to me was thinking, what if this mayor was a copycat mayor — taking another mayor’s idea from another bleak place. But it had to be real. It had to be about actual hopelessness and the true feeling that people might have that they’re not sure there’s enough to sustain another life in this place. In the writing of it, the pleasure was in going back and forth between the funniness of the situation and the real hurt underneath, the real fear.

If you have something funny, it breaks a reader open and makes all of the sadness and darkness sort of flood into that space.

LS: From bleak towns to Turkey to Africa, the stories move around a lot, to places real and imagined. I felt, particularly for the real places, that the collection was Eastward facing. Beirut comes up several times — two mothers, in “Freshwater” and in “Mother Land” go to Beirut to die, essentially. What’s the background on your interest in the East?

RA: Well, I started the story, “Club Zeus,” after I got married and we went to Turkey and Greece on our honeymoon. We had a day at this all-inclusive resort and I was like “What?! This is a real place? This is not something from a George Saunders story?” I knew that I wanted to set something there but it took me a long time how to figure out how to make this story something more than just like, “This is weird place.” So, that was the first story that was sort of cast out into the world.

A few years later, my husband and I took a trip that lasted almost a year and a lot of the places we went are in the book. When we were travelling, I thought I was writing a book of nonfiction, I thought that it was a book about the idea of starting a family at this moment on the planet what with all of the terrible things that are happening. And I was thinking about that for myself — is having children even a good idea, is that okay to do? I did a lot of interviews with people all over the world, but about halfway through I realized that I didn’t want to write a nonfiction book. That it wasn’t my book to write at all. If somebody else wrote it, I would absolutely read it but it just didn’t feel like my work to do. Writing a book is such an investment, you have to be willing to hold it in your heart for years and years. I realized I was not willing to do that with that book.

Every Inheritance Has a Shadow

At first I was very despairing and I thought that I’d squandered this opportunity and the little fellowship I’d gotten, that it was all a waste. But when we came home, I started playing around with some stories, and the first one that I wrote after that was “The Animal Mummies Wish to Thank the Following.” And I really liked those animals. I thought, these guys are going to hang out with me and they are going to be pals and they are going to help the next thing happen. Slowly the stories started to emerge, and I realized they were set in all these different places and in fact all of that work I had done, the interviews, were part of a book. It was just a very different book than the one I imagined — instead of thinking about it from the outside as something I thought the world might want, it came from very much inside. I needed to write for my own reasons, and that’s exactly why it’s such a weird collection.

We were only in Beirut for a few days, but there’s just a quality to the city. Buildings are basically bombed out but it’s right on the ocean and everyone’s hanging out, jumping into the water. It felt like there was a very strong feeling of love for the place, and an ever-present fear of what has happened and what could happen. As a total outsider, I imagined loving somewhere like that, how that might be such a strong magnet in a person’s life.

LS: Were many of the destinations seaside countries? I ask because water features really prominently in this collection, and in a way that’s specific to women. A number of women emerge from the sea, and are drawn to the sea. Do you feel very drawn to the ocean, to water? Or do you think there’s a special connection between women and the sea?

RA: I do feel very drawn. Partly because I grew up in the desert. I lived the first half of my life in New Mexico and the second half, up until last year, in California, so all of a sudden, the sea was part of my existence. It’s just so, so vast, such a huge presence and so unknown to us; beautiful but dangerous. We’ve explored something like 10 percent of the world’s oceans, and we really don’t know a lot about what’s down there, which feels like a beguiling mystery but also like a threat. If there’s a storm or if you go out beyond where you are safe, you will be subsumed and completely disappear. I’m interested in what happens in this realm that exists on the edges of our world, and all of the things alive down there.

I needed to write for my own reasons, and that’s exactly why it’s such a weird collection.

LS: There was a real sense in the last section of this book that the stories took place in a realm or a bardo of some sort, or maybe purgatory. Can you tell me the decision to end the collection in a place that is the least defined, in a way?

RA: I played around with the arrangement a lot. I wanted it to be in some recognizable places, like the first story, “You Can Find Love Now,” is about a cyclops but he is very much in Washington State. The funniness of the piece is that he’s this strange otherworldly creature who’s supposed to be in Greece, but he isn’t, here he is in Washington. I wanted it to start with sort of the weirdness, but the rootedness at the same time, and then come back around to these places, to leave this earth, basically.

The last story, “Do Not Save the Ferocious,” sort of takes place in the North Sea and is maybe somewhere in Scandinavia a long time ago, but it isn’t at all defined. It feels like it could be any time and it maybe could be a place on this planet at all after all. The characters have, in their minds, certainly left the planet. It’s clear that they have made some kind of departure, and I wanted to make that story about departure. I also wanted it to be about the way our imaginations and the places we live in in our minds are separate from the world. Our feet are on the ground, but we’re also existing in other places, and maybe some of those places are real, but some are imaginings that don’t exist. There’s another world happening at the same time the regular world is happening. I wanted to go take us all the way outside.