essays

Reading “The Idiot” Was the First Time I Felt Like Part of the Story

Elif Batuman’s writing finally let me see my Turkish American experience reflected on the page

I haven’t heard of Elif Batuman — brainy, hilarious essayist and novelist — until I go exercising at a Snap Fitness 24–7 location near my apartment one afternoon. It is January 27, 2011, a day I only remember because I will later send myself an email and archive it. Subject line: TODAY I FOUND ELIF.

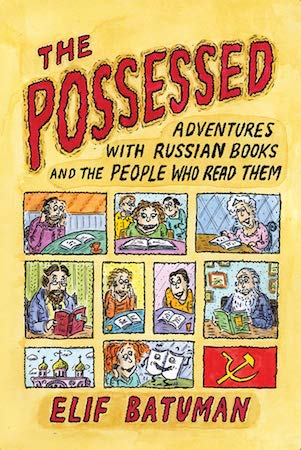

This particular gym is managed by two enormous, suntanned brothers who want me to invest in their diet smoothie pyramid scheme. The brothers have recently purchased a state-of-the-art stairclimber, the crown jewel of their fitness franchise. We have to sign up for it on a special clipboard. The person on the climber before me that day leaves a women’s magazine behind on the reading rack. The magazine is one of those Christmas gift guide issues filled with photos of luxury candles and control-top pantyhose. A bit weirdly, there is also a suggestion that, for the bibliophiles in our life, we should all purchase Batuman’s new memoir, a collection of essays called The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them.

When I see the blurb, I have no reason to believe this book will change my life. First of all, I have never embarked on an adventure with a Russian, or even a Russian book, so I don’t feel I fit the target audience. But the book does change my life. It changes my life before I even read it.

It’s not an exaggeration to say as soon as I see the author’s name, I launch myself off the stairclimber like a mountain goat in flight, and sprint back to my apartment, abandoning my workout in order to conduct a thorough Google search. It turns out Batuman has written for the Atlantic, for the New Yorker, for the literary journal n+1. She has published a funny piece about a Thai kickboxing champion, written about ice palaces, Central Asian landladies, and how to find a good watermelon when in Uzbekistan. She has written about it all.

The book does change my life. It changes my life before I even read it.

At my kitchen table that afternoon, I discover Batuman’s personal blog, and immediately enter an alternative-reality fugue state where everything not on the screen vanishes. All I can do is keep reading and reading until finally, I look up and realize it is pitch dark and I haven’t moved for about four hours. My sweaty clothes have long dried and stiffened. My thigh muscles are frozen tight.

The blog, which is no longer available online, tells me about Elif’s life, her experiences as a graduate student, as a writer, as the only child of Turkish immigrants. It is my gateway drug. It leads me deeper, and to other things: to print interviews, to her Twitter feed, to NPR conversations, and a scathing, brilliant essay she has written, for the London Review of Books, on the strange obsession creative writing programs have with craft (“What did craft ever try to say about the world, the human condition, or the search for meaning? All it had were its negative dictates: ‘Show, don’t tell’; ‘Murder your darlings’; ‘Omit needless words.’ As if writing were a matter of overcoming bad habits — of omitting needless words.”).

I order The Possessed straight away, rush delivery, hardcopy, yes, please send the free sample chapters to my inbox. Then, I write an email to my entire family, subject line: İnanılmaz bir Türk Amerikalı yazar buldum. Translation: I’ve found an incredible Turkish American writer — which is true, but it is incomplete. Batuman isn’t just an incredible Turkish American writer. She is the incredible Turkish American writer. She is the only one.

Batuman isn’t just an incredible Turkish American writer. She is the incredible Turkish American writer. She is the only one.

If I were to write a story about my life, my protagonist-self would be, like Batuman, the only child of Turkish immigrants. My tale would be one of general nerdiness and loneliness and cycling up and down the same stretch of sidewalk on a ten-speed. It would be a story of not having a boyfriend until the age of 20, and most scenes would take place on the couch, me in loungewear, reading about Narnia.

Some loners are video game-enthusiasts. Some grow heirloom tomatoes. For me, it has always, always been about books. But in all that time, years upon years, stories upon stories, I have never encountered a heroine who speaks Turkish like I do, who grew up in between here and there; someone whose experiences, in some fundamental way, mirror my own. Until now.

After The Possessed is delivered, I race home after work every day to devour Batuman’s words. I am thrilled to find essays about America and Turkey and the former Soviet Union’s Turkic republics. In one piece, Batuman recounts a trip to Kayseri, the “Turkish pastrami capital.” In another, she describes her uncle, a man who “spent his later years in a gardening shed in New Jersey, writing a book about string theory and spiders.” She shares her adventures in Uzbekistan, where she survives on “some kind of chocolate spread” eating it directly from the jar with a “souvenir Uzbek scimitar.” She attempts to learn old Uzbek, a language with 70 words for duck, 100 words for crying.

There is something mildly bonkers/deeply resonant about every single essay, and by the time I finish the book, I am electrified in a way I have never been before. I have only read about this part of the world, ostensibly “my” part of the world, through the eyes of European writers, usually white men. The Possessed is different. It is richer, feels truer to life, free of condescension and bad stereotypes about what it means to be Turkish. It is an infinite improvement over everything that’s come before.

When Elif’s debut literary novel The Idiot, about Selin Karadag, a Turkish American first-year college student, is announced, I set up a Google alert for it and begin the wait. That winter, I preorder online, and read the first chapter, previewed in a January issue of the New Yorker. When a troll launches a Twitter-attack on Elif, I secretly report him every day until he eventually disappears.

I read The Idiot slowly, savoring it, dog-earing the pages. Some chapters I finish, then go back and immediately read again. Some parts I read out loud to my best friend. Some parts make me cry. Never has the act of reading been a means of such profound self-affirmation.

I love Selin, the type of bookish, dorky, peculiar character chronically underloved and overlooked in literature. I love her for the silent “g” in her super Turkish last name. I love her for her observation of a dinner buffet in a Mediterranean resort town (it has a “kebab station and a swan made of butter sweating in a tub of ice”), and for her hilarious visit to Turkey’s first golf hotel, where she rides around in a golf cart with a man shaped like a barrel.

When I meet Selin on the page for the first time, I am pushed to examine how I’ve accepted a lack of representation, or bad representation, as the norm for all these years. Selin shows me what I’ve suspected all along: that something different is possible. She helps me see, after decades of watching from the sidelines, mute and passive, maligned or ignored, what it is to finally become part of the plot.

She helps me see, after decades of watching from the sidelines, mute and passive, maligned or ignored, what it is to finally become part of the plot.

Three years ago, before the release of The Idiot, Elif published an essay in the New Yorker on reading racist literature. “As a Turkish American, I couldn’t prevent myself from registering all the slights against Turkish people that I encountered in European books,” she writes. “In Heidi, the meanest goat is called ‘the Great Turk’;” in the Agatha Christie novel, Dumb Witness, someone decides it’s “rather dreadful for an English girl to marry a Turk,” as it “shows a certain lack of fastidiousness.”

Elif describes these encounters as mildly jarring. “There I’d be, reading along,” she says, “imaginatively projecting myself into the character most suitable for imaginative projection, forgetting through suspension of disbelief the differences that separated me from that character — and then I’d come across a line like ‘These Turks took a pleasure in torturing children’ (The Brothers Karamazov).”

After I finish Elif’s essay, I print it out and pin it to a cork board in my office. I feel defiant. The first paragraph alone makes me want to march out of the building and start a riot. Every act of literary cruelty and exclusion has diluted and erased the richness, the fullness of experience not just of Turks, but of people of color; of women and the LGBTQ; of immigrants; of the poor.

Every act of literary cruelty and exclusion has diluted and erased the richness, the fullness of experience… of people of color; of women and the LGBTQ; of immigrants; of the poor.

But suddenly, here is Elif. Here is Elif, beginning to do what no one else in this country’s Turkish community has done before. Here is Elif, gently pointing the finger at what’s wrong, showing us there is a better way.

I am spending the winter in Istanbul. I am staying for a full month, and will be on the same college campus where Elif is writer-in-residence. I’ve never been to this campus before. It’s relatively new, and has been built atop a hill, surrounded by a thick forest of birch and chestnut, looking down onto the Black Sea coast.

I don’t think I should email Elif. I have her email, I found it on her blog, I think, but I don’t want to use it, because what would I even say? That I’m a big fan? I think it’s weird to be a big fan, especially at my age. Twelve-year-olds can be a “big fan;” can fangirl over someone. I’m pretty sure there’s no such thing as a fanwoman and if there is, I don’t want to be one.

Twelve-year-olds can be a ‘big fan;’ can fangirl over someone. I’m pretty sure there’s no such thing as a fanwoman and if there is, I don’t want to be one.

So I don’t email her. Not for, like, a week — which for an Aries, is roughly equivalent to one calendar year. I hold out that long until one night, my friend Çağla comes over to my place for dinner, mentions she just saw Elif at the bus stop across the street, and the next thing I know, Çağla and I are drafting an email on my laptop. I convince myself it’s okay to do this because Elif isn’t just any writer. She’s someone who has written, with humor and grace and smarts, about the complicated, messy particularities of her life as a Turkish American young woman and, in the process, has given me the courage to do the same.

I don’t remember exactly what I say in the email, but I remember I try my best to sound jokey and not like a serial murderer. I invite Elif to a picnic Çağla and I are organizing in Kilyos that Sunday. I tell Elif I’m a “big fan” of her blog; that I follow her on social media. I try to keep it short. I make sure to use spellcheck.

As soon as I hit “send” I am filled immediately with regret, and already predicting my future embarrassment at this picnic, but it turns out I don’t need to worry. Although Elif will write back, gracious and kind, she will not be able to make it to Kilyos on Sunday. I’m glad she won’t. Honestly, I am. I’m sad for a minute, but then relieved, because I know what they say about never meeting your heroes. People say that. They say it all the time.

Years later, long after I’ve left Istanbul, I will try, shaky and green, to write a short story about a Turkish American girl. I will name her Elif. This is my smoke signal, a tip of the hat to show: she paved the way. She had things to say that I needed to hear. She saw the humanity, the humor, the stories in us so that I could, too. She made me feel like we’re all in this together.