Craft

Reclaiming A Lost Tribal Language: How, and at What Cost?

Confronting privilege, tradition, and conflicting ideas about cultural preservation of the Wampanoag Tribe

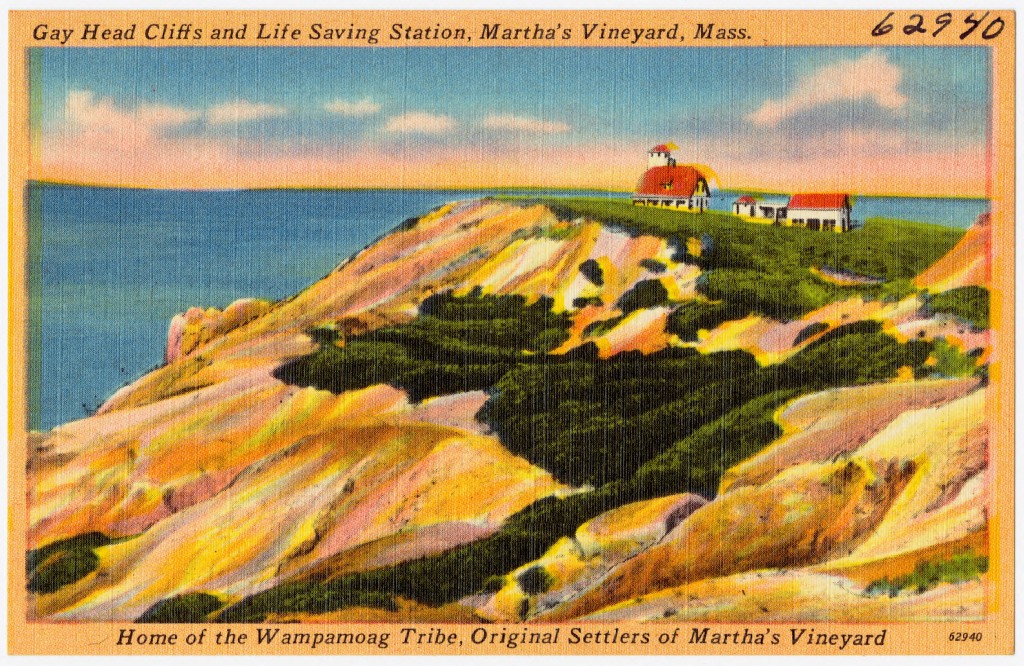

Growing up, I spent summers going to the Turtle Project, which was a camp for Aquinnah Wampanoag kids run by our tribe. Aquinnah is a small town on the far end of Martha’s Vineyard. Every year the island swells with seasonal tourists flocking to its idyllic beaches and picturesque towns. Although I never considered myself a tourist because of my familial and cultural ties to the island, my childhood experiences there mostly matched up with the tourists’.

We would spend all day at the beach or the famous Agricultural Fair in August. For a couple years, a woman named Jessie Little Doe Baird ran the camp. Before Baird took over, we spent our days playing outside and learning about local wildlife. With Baird, we spent most of the beautiful summer days inside, learning Wampanoag language and traditions. I remember one trip we made to a local beach; we were learning how to track animals in the dunes and we weren’t even allowed to go in the water. I don’t know who was responsible for the change, but around this time I remember being irritated that we weren’t supposed to call the Turtle Project a “camp,” because we were there to learn, not just have fun.

We weren’t supposed to call the Turtle Project a ‘camp,’ because we were there to learn, not just have fun.

Baird’s tribe, the Mashpee Wampanoag, and my tribe, the Aquinnah Wampanoag, are sister tribes. Related, but separate. Shared histories, similar customs, but separate governments and individual stories. Geographically too, our tribes are very close. Mashpee, a small town in Cape Cod, is a short boat ride away. Mashpee has one of the biggest East Coast powwows. Each summer, in the height of powwow season, their powwow attracts the best dancers and the biggest crowds. Fireball, a dangerous cleansing ritual performed by playing a game with, well, a fireball, is a legendary highlight of the Mashpee powwow. We have a new powwow organized by our youth group that’s at the tail end of powwow season in September. Local dancers and tourists who happen to be there make up most of the crowd. There is a familial rivalry and closeness between the two tribes. In fact, Baird is married to an Aquinnah Wampanoag — our Medicine Man.

My senior year of high school, I went to see We Still Live Here, a documentary film, with my mom. The film is about Baird’s mission to recover the Wampanoag language, which no one had spoken fluently for generations. Baird was leading the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project and had received a Master’s degree from MIT to help her do so. The screening, which took place at the Brattle Theatre in Harvard Square, was followed by a Q&A with Baird and its director, Anne Makepeace. My mom and I drove from our home in Newton, where I had grown up, into Cambridge for the event. In the dark Brattle Theatre, there was an older white man sitting next to me. He’d shoot me a dirty look every time I whispered a comment to my mom during the movie. I imagined he was thinking something about disrespectful kids. At the beginning of the Q&A, Baird made a point of thanking the two Wampanoags in the audience — me and my mom. She asked us to stand and I think there was a round of applause for us. After I sat down, the man next to me smiled at me and extended his hand for me to shake. I shook it.

Baird is raising her daughter as the first native speaker of Wampanoag in seven generations. The film devotes a lot of space to this narrative. More advanced students, Baird says, are crucial to the spread and development of the language but there are not nearly enough of them. Her daughter, though, is the great hope. Baird has a line that goes, “if she’s the first [native speaker], there necessarily has to be a second and a third and a fourth.” I never got that. Why does that have to be true? What if she is the first and last? Destiny is a compelling narrative, one that is reinforced by the film’s use of animated words that transform into animals, scenery, or shadowy Wampanoag ancestors. This device makes the film’s story more about destiny and history than any kind of modern narrative. Baird’s motivation for starting to work with the language also speaks to the pervasiveness of the trope that Native culture only exists in the past.

Baird is raising her daughter as the first native speaker of Wampanoag in seven generations.

Baird’s story, which she recounts in the film, began in the early ’90s, when she had a recurring dream. In the dream, she heard people speaking in a language she did not understand or recognize. Eventually, Baird came to realize that they were speaking in her native language, a language no one spoke anymore. Baird went on to found the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project in the aftermath of that dream, culminating in her enrollment at MIT in the late ’90s.

Later, she was also awarded a MacArthur Foundation Grant, which came with a $500,000 prize. Baird graduated from MIT in 2000, after working closely with Ken Hale, a celebrated linguist. Baird tells a story of the first time they met. He came by the tribe to give a talk. Baird laughs and says that she was quite disrespectful to him, challenging his whiteness and calling him out on a small mistake he made. When she showed up at MIT, she was appalled to learn that Ken was the expert she’d be working with. She went to his office full of trepidation and ready to dump a big fat apology on his desk in the hopes that he would help with her project. Before she could apologize, he welcomed her with, “I’ve been waiting for you.” It’s like a scene from a ninja legend — the aged master, waiting years for the promised apprentice to show up at his doorstep. The movie endows this line with the same kind of mystic power that it gives to Baird’s dreams and her insistence that her daughter is the start of a new generation of native speakers.

I’m especially sensitive to framing Native culture in this way because I know how most people think of us. You’re not a Real Indian unless you are wearing feathers in your hair and beating a drum or hunting buffalo and Using Every Part. The American imagination of Native Americans relies on a few whitewashed historical examples and stereotypes.

Whenever I tell someone about the language project, they almost always ask if I can tell them how to say something. Sometimes I feel like just telling them something that I know will satisfy them, but sharing language with curious strangers feels like giving in to their exoticized image of a Native person. I’m also reluctant to share because I’m embarrassed at how little of the language I know. But even if I could get over those fears, I feel uncomfortable because I don’t really know what I’m allowed to share or not. Baird has often insisted on what I’ve always found to be a confusing level of secrecy about the language. Except for family of tribal members, non-tribal members are not allowed into language classes. I would have thought making a language as accessible as possible would only help its rehabilitation. Yes, Baird explained to me once, but the language is accessible to those who need it. It’s not for anyone else. But then who is the movie for? The broader context for the movie is the reality of how and why people consume Native American cultural narratives.

I know how most people think of us. You’re not a Real Indian unless you are wearing feathers in your hair and beating a drum or hunting buffalo and Using Every Part.

Part of this context is Caleb’s Crossing, the 2011 novel Geraldine Brooks, a bestselling author from Australia, wrote about the first Wampanoag to graduate from Harvard’s 17th century Indian College. Before publication, Brooks sent her manuscript to Baird and another historian in the tribe to look over for cultural accuracy. Baird had done this for other writers, only to be ignored, so she decided not to waste her time. The other historian replied in detail to Brooks about a number of problems, like a story about an Englishman’s toes getting cut off and eaten by his Wampanoag captors. We didn’t actually eat toes, she told her. I also heard that the novel played it fast and loose with the language. Brooks completely ignored these comments. I was outraged. Months later, after the book was already a bestseller, Brooks did a reading at the Aquinnah Town Hall, which was packed for the event. Most of the people who came were non-Tribal town residents but there were a few Tribal members in the audience. One of them stood up to thank Brooks for honoring us with her beautiful depiction of the tribe.

My mom went up to Brooks after the reading and told her that she had some serious reservations about the book. Brooks thanked her for expressing her feelings and moved on to a crowd of fans. I was so proud of my mom for standing up to a famous author, but felt a sense of loss after the talk. Nothing had changed. After listening to my whining for a week or so, my mom told me that if it bothered me so much, maybe I should write my own book about the tribe. She’s right, but I’m almost paralyzed by anxiety over how a book about the tribe could ever be “mine.” This fear is based in my own insecurity about being an authentic tribal member. I don’t know what such a person looks like but I’ve always felt that living mostly off-Island makes me less Wampanoag somehow. But as much as I feel I’m not representative of the typical Tribal member, living off-Island actually makes me more representative than if I didn’t: only about 20% of the tribe lives on Martha’s Vineyard and less than half of those live in Aquinnah. The more I think about it, the more I realize that what makes me most uncomfortable about speaking on behalf of the tribe is my own privilege. Living off-Island doesn’t make me atypical, but attending graduate school at Columbia might. Does this privilege give me different responsibilities?

There are different kinds of privilege. Unlike Baird and so many others, I’ve never known what it’s like to not have my Native language. I may not be fluent, but I grew up learning the language during those summers. And so I take its presence for granted and question how and why it’s being employed more than how it can be recovered and preserved.

Even though Anne Makepeace made the movie, we think of it as “Jessie Baird’s movie.” Nobody has questioned Anne Makepeace’s intent. Certainly nothing close to the criticism Geraldine Brooks received. Brooks came in as an outsider and told the story the way she wanted to. Baird was allowed to tell her story the way she wanted to. But on whose terms? In the movie, the ancient texts turning into elegant cartoons of Wampanoag ancestors, the drumming scenes, Baird’s professed fear of not understanding the “big city” of Boston — they all add up to something. Why do we have to want our language back only because the Wampanoag ancestors in Baird’s dreams told her to? The film implies that Wampanoag people need the language to more fully embody our Tribal entities — and maybe we do, but there’s a slippery slope from there to suggesting that Native people can only be authentic by living distinctly un-modern lifestyles. We Still Live Here is great with particulars — the nuts and bolts of language class or occasional specific linguistic developments, but I worry that the movie will be just another achievement in the cultural trophy case of people like the man who shook my hand in the Brattle Theatre.

Unlike Baird and so many others, I’ve never known what it’s like to not have my Native language.

Baird is not the only Native person fiercely protecting our culture through secrecy. Leslie Marmon Silko is one of the most prominent Native American writers. Her 1977 novel Ceremony is her most famous book; four years after it was published she won the same Macarthur Grant that Baird would win years later. And yet the novel was criticized for using too many tribal traditions — traditions that Puebla poet Paula Gunn Allen said were not meant to be shared with non-Tribal members. The Macarthur Foundation website’s blurb about Silko states that she is “a writer, poet, and filmmaker who uses storytelling to promote the cultural survival of Native American people.” Can Silko be promoting cultural survival when she is being called out for inappropriately putting that same culture on display?

Last spring, JK Rowling wrote a story on her Harry Potter website Pottermore called “A History of Magic in North America,” which inevitably included a description of Native magicians. Dr. Adrienne Keene, a Native scholar and blogger, responded to one of the few specific details in the story: the legend of the ‘skinwalkers.’ The Skinwalker is a real Navajo legend and Keene’s response to Rowling’s incorporation of this real legend echoes Baird: “these are not things that need or should be discussed by outsiders. At all. I’m sorry if that seems ‘unfair,’ but that’s how our cultures survive.” In other words, Keene is making the same argument that Paula Gunn Allen made about Ceremony and Baird makes about the language: we don’t owe you anything. It’s not surprising that the Macarthur Foundation and Native activists have very different ideas about how Native culture can and should “survive,” but they do use the same word to describe what they believe they are doing. I’ve learned that cultural preservation can be inward or outward facing but not both.

I wonder how much these pushes for secrecy are motivated by a desire to be able to claim absolute ownership of something for once. I can identify with that desire. One year in Turtle Project we were taught the “true” story of the first Thanksgiving. The story we had been taught in school, we were told, was a lie. We were also told not to share this new version with non-Tribal members. I felt a rush of excitement upon learning this new version of the Thanksgiving story. During this time, I was also learning about the bad things colonialism had brought to Native people and had decided I didn’t want to be friends with any “Europeans.” Beyond the youthful excitement of knowing a secret, I was especially excited about knowing a secret that felt so transgressive and anti-European. I loved the idea of having this knowledge and refusing to share it. But if the story I was being told was indeed a more accurate version of an important American story, then why were we being told not to share it? And anyway, I’m pretty sure the “secret” version I learned is generally accepted as the true, non-Hallmark version of the event by Europeans and non-Europeans alike. Adrienne Keene and the others have the right, of course, to do whatever they feel is necessary to protect their Tribal cultures. But I believe we also have the responsibility of asking what motivates that desire. And what if our ideas on how to best protect our cultures are directly opposed to one another?

Last year, I called Baird to ask her some questions about the progress of the language project. During the call, Baird credited much of the positive publicity around the Language Project to the movie. She recently founded a Wampanoag language immersion school. So in that way, I can see how the movie has done concrete good for its subjects. But at what price? And who ends up paying that price? I didn’t ask her these questions, but I wish I had.

I’m still hesitant asking harder questions when I talk to Tribal members, especially such well-respected ones. The film gives an unfamiliar audience insight into my tribe, but ends up being the end of a conversation instead of the beginning. Through its reliance on stereotypes (employed equally by white filmmakers and Tribal members) the film does little more than confirm what many viewers already believe before watching the film. To what extent is the film responsible for the assumptions of its audience? In the end, I think the movie tells the story it means to tell: Baird’s story. But I’m sure that most people who see the movie see The Wampanoag Story. And that’s not to say that’s entirely inaccurate. Maybe it’s just an inevitable problem of using one person, no matter how emblematic, to tell the story of an entire group of people. And not a legendary figure from the past, but a living, imperfect, and utterly real person. And it is impossible; to all Wampanoag people, Baird is the embodiment of the drive to recover our language. In this case, she does represent Wampanoag language recovery efforts, but is that the subject of the film as most viewers will understand it?

The film gives an unfamiliar audience insight into my tribe, but ends up being the end of a conversation instead of the beginning.

During the same phone call, I asked her how she weighed the different benefits that came with bringing back the language. She explained to me how, in the Mashpee land suit with the state of Massachusetts to get land in trust to build a casino, she was able to translate centuries-old records and place names that demonstrated Wampanoag presence on those same lands hundreds of years ago. The land in trust application required historical record that the Mashpee have only recently been able to provide. In other words, access to previously lost language is helping them get their casino, which she assumed I supported. She didn’t realize that I’m dubious of the casino projects both of our tribes are pursuing. Maybe I should have told her how I felt, but I’m again self-conscious of my own privilege. I don’t know the financial situation of the tribe or other Tribal families, but I do know that my family lives pretty comfortably. We don’t necessarily need the money. So I’m free to reject the idea of non-Native developers coming onto our land and taking advantage of one of our few special rights without worrying about the money I might be sacrificing.

Last spring, the Mashpee Tribe announced accelerated plans for their billion-dollar resort casino project. The 2017 scheduled completion date beats their competition by a year; the announcement was greeted by rousing cheers from the tribal community. “To all the doubters,” crowed Tribal Chairman Cedric Cromwell, “sorry.” The tribe also unveiled renderings of what the finished product will look like. For the most part, it looks like any other modern resort: shining glass towers, beautifully cultivated greenery, and all the other bells and whistles. The main entrance is modeled after a traditional Wampanoag dwelling, reminding all visitors whose casino they are visiting. This makes me feel sad and disappointed. A tourist trap novelty entrance to a resort casino doesn’t reflect well on anyone involved. Maybe that’s not fair, but I can’t help but be critical of what seems to be blatant culture commodification. Marginalization is not always something done to you by others.

Two years ago, I ran into Baird at a Native Artisan’s Fair organized by the Aquinnah Cultural Center. I was selling Wampum jewelry made by a cousin. She asked me how school was and what my plans were. I told her how I was about to start an MFA in New York. That’s great, she told me, we need writers. Tell our story.