interviews

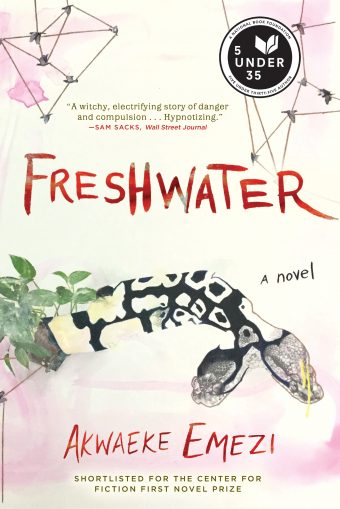

How to Move Between Realities

Akwaeke Emezi, author of ‘Freshwater,’ talks about immersing herself in Igbo ontology and her many selves

Akwaeke Emezi’s debut novel Freshwater is an arresting psychological portrait that re-centers African realities overwritten by colonization. To read the novel is to enter, and become immersed in, its vivid metaphysics. Grounded in Igbo ontology and drawing on Emezi’s own life, Freshwater tells the story of Ada, a young Nigerian woman who is born “with one foot on the other side.”

Ada is an ogbanje, an embodied Igbo spirit, and she begins to develop separate selves as a child, replete with their own desires and urges.When Ada moves to the U.S. for college and experiences an act of sexual violence, these selves assume greater power and agency in her consciousness.

Told from multiple perspectives, the novel braids together the voices of Ada, the self she calls Asughara, and a collective voice of her plural spirit, referred to as “We.” In our conversation, Emezi and I discussed the politics of naming, and the reclamation of marginalized realities.

Tajja Isen: I wanted to start with something you say in the acknowledgments. You write that your sister advised you to treat the writing process “like [you were] a method actor, to surrender.” What does it mean for you to approach your work as a method actor?

Akwaeke Emezi: So, Freshwater is based in a very specific reality, Igbo, and it wasn’t one that I had much experience in before writing it. I was raised Catholic, and we’re not really taught much about our traditional religions growing up in Nigeria. The book is set firmly within Igbo ontology, though, so it was impossible to write it without completely surrendering to it, which meant immersing myself in these beliefs. My concern when I started was that I would enter this other reality and not be able to get out of it. I took my sister’s advice and it worked out, but interestingly, I was also right: stepping into Igbo wasn’t really a reversible process, but it turned out for the better. Once the book was done, I had a lot more clarity about myself than I did in the beginning, and using that specific reality as a lens was the only thing that made that possible.

My concern when I started was that I would enter this other reality and not be able to get out of it.

I also realized I wasn’t the only person who was trying to figure these things out — specifically, trying to figure them out when it comes to these indigenous realities that we lost access to through colonialism, replaced by very Western norms of Christianity and science. What you end up with is a bunch of people who are living in ways that they can’t talk about, because if they do, they’re either going to be labeled as “crazy” or “possessed by a demon.” Freshwater, in a sense, is a story that’s also a reconstruction of my life through a completely different lens. It’s like trying on a pair of glasses and realizing, “Oh, these should have been your eyes all along.”

TI: I see that in the novel as well; there’s such a strong sense that the act of naming gives something its power.

AE: Yes, very much.

TI: Do you describe these Igbo narratives using the word “mythology”? I hesitated to use that word.

AE: The word “mythology” implies that it’s not real, that it’s make believe. I had to do a lot of re-centering where I was raised with it being, “this is mythology, this is folklore, this is superstition.” Then you ask a couple of questions and you realize the only reason it’s considered make-believe is because a bunch of white people showed up and told everyone there that the reality they’d been living in was fake, and they’d been believing things that weren’t real. And then that really jolts your understanding of what is real. Which is why a lot of the work I do with Freshwater, and with other work, is about allowing for multiple realities to exist at the same time, versus the concept that there has to be a singular, dominant one and everything else gets defined according to that. So I hope that Freshwater shifts away from that a little bit and allows for multiple ways of being.

The only reason [Igbo folklore] is considered make-believe is because a bunch of white people showed up and told everyone there that the reality they’d been living in was fake.

I use the word “ontology” and at first I thought it was a bit pretentious, but then I realized it was actually very useful. When we were trying to figure out the copy around the book, I said that, because I’m Nigerian, if we used the word “identity” people would assume that it’s about national identity, or racial identity—but no, it’s about metaphysical identity. It’s not about all these human categories that we place bodies in, it’s about the step before that, of being placed into a body in the first place. There are a lot of things that happen to the flesh [in the novel] that are considered brutal, but for me the main brutality in the book is the existence as flesh in the first place. All the other stuff, as bad as it is, isn’t as bad as that.

TI: For me, the moment when I recognized the violence of embodiment was the accident early on with Ada’s sister Añuli, when she’s crossing the road.

AE: I really like that insight, because it’s not actually centered on the Ada. In a way I think seeing the pain or the fragility of a body has more impact when you’re watching it happen to someone you care about versus it actually happening to yourself.

TI: And that’s also what instigates the desire for blood in the selves.

AE: The thing I like about realities, specifically those that are indigenous to Africa— and sometimes move to the diaspora — is that there are certain things that are always true. One of them is about the role of blood. There’s a quote from Zora Neale Hurston which says, “All gods who receive homage are cruel. All gods dispense suffering without reason […] Half gods are worshipped in wine and flowers. Real gods require blood.” And that last sentence is a fact that is acknowledged across all kinds of realities. Even in Christianity.

That’s one of the things that was interesting about writing Freshwater: these realizations of how much of personal experience can tie into a larger lived experience that involves a lot more people. I think that’s the experience some readers have had — they’ve been having an experience within their heads and they read the book and they get that validation that I got when I was doing my research — “I’m not crazy, this is true in someone else’s reality, which means that I have a community in a sense.”

TI: Do you think there’s something in these ontologies that also helps make sense of desire — both sexual desire and human urges?

AE: I thought about that and it’s hard for me to think about desire in the context of the book because so much of the desire there is different from, as you put it, “human urges.” So even for Asughara, for instance, her quote-unquote “sexual desires” are not really about sex at all.

TI: Right, it’s about protection of the Ada.

AE: It’s about protection. It’s about attack. It’s a weapon, it’s about trying to feel alive or not feel dead, it’s about trying to feel more embodied. So it’s all these things that are, again, not really centered on being human, but inhabiting that paradox of not being human and still having human form. And Asughara is the self who has a lot of desires. They’re not necessarily human urges — for her specifically it’s like the pain of embodiment, or how to stop that dissonance. A desire for death; a desire to go home. If you’re inhabiting human form, then it makes sense that your urges would overlap with human urges—and that on the surface, they would look the same. The urge to go home is such a human thing, but in the case of the book, to go home means to die. So there are layers to it, where the top layer is shared across humans and non-humans alike.

It’s about trying to feel alive or not feel dead, it’s about trying to feel more embodied.

I tried to have the reader feel what that dissonance is like, where you have the layer of flesh but you also have this other layer. And you can’t really separate one from the other. And Ada tries to split them apart and get rid of the selves and she’s making all these little boxes, which is a very human thing to do, to make boxes and try and make everything fit neatly, and it’s still all just a jumbled, overlapping mess.

TI: I definitely felt in myself the impulse to spatialize and separate and figure out where the borders between the selves were, but as I was reading, the novel taught me to resist that logic.

AE: I mean, it’s a very natural impulse to try and start that way. I was having a conversation with someone about the book being kind of autobiographical. We were talking about the selves, and they were asking how they work with me now, outside the book. It wasn’t until after writing the book that I realized that even the demarcations that [Ada] creates are kind of arbitrary and false, and as easily as she can create those selves, they can collapse. So when I was answering my friend’s question — “how do your selves work, which one am I talking to” — I said, “I have no idea!”

The image I use for it is like a boiling cloud, and it’s just a lot of [selves] boiling in there, and sometimes one or two will precipitate out, the way they did in the book, and be around for a while, and then they’ll disappear and it’ll all be mixed up. But part of what I learned from writing the book is to accept that even though I made these different, bordered selves to write the book, they’re constructs. They’re things that Ada created to make what was happening in her head make more sense, because at the time, she/I didn’t have the understanding that all of it could exist at once. It was too complicated a concept. It’s simpler when you divide it and when you make the little boxes. Now I’m better at not dividing it and just accepting the mishmash and layers.

TI: How do you think that will inform your work going forward?

Once you let go of a singular reality, you also have to let go of a couple of other things, like time functioning the way that it would normally.

AE: I think it helps because one of the things about shifting through selves and realities frequently is that it makes it very easy to write fiction — it’s easy to embody other people. I’ve tried writing with one central character, and it’s very challenging for me, because to restrict it to one person is hard. And so my second novel manuscript is also written from multiple points of view and that’s more natural for me, to slip between people. I need a lot of people — I think that’s how it shows up in my work. At least when it’s a book-length work, I need a lot of people because I can’t really stay in one reality for that long.

TI: How does that process of moving between perspectives inform the work of writing?

AE: It’s usually not very linear. There’s a thing about linearity, and binaries, and these very structured things are supposed to move in one direction, and I think there’s something linked about all of that. Once you let go of a singular reality, you also have to let go of a couple of other things, like time functioning the way that it would normally.

I think it’s about a learned flexibility. Once you learn to be flexible with realities, you become flexible about borders, you become flexible about time, you become flexible about a lot of other things, which I think is a really good quality to have just because it makes you a lot more tolerant of other people. If you’re too rigid, you won’t have room for other people’s realities, which is the root of a lot of problems in society. People are so against accepting alternate existences, that they will kill to make sure that a different reality doesn’t threaten theirs.