Recommended Reading

Remember This: Love Is a Verb

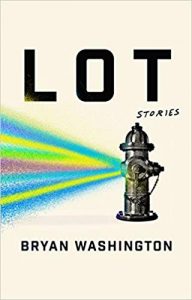

“Lot” by Bryan Washington is a story about one Houston family’s attempt to deal with gentrification and loss

INTRODUCTION BY AJA GABEL

To point out that Bryan Washington’s stories are deeply concerned with place is to state the obvious, but it’s how he does it that’s worth pointing out. Washington’s stories evoke a Houston, Texas that appeals not because it’s universal and not because it’s idiosyncratic, but because it’s specific to a thinly sliced layer of life lived on a particular street in a particular season in a particular body.

To point out that Bryan Washington’s stories are deeply concerned with place is to state the obvious, but it’s how he does it that’s worth pointing out. Washington’s stories evoke a Houston, Texas that appeals not because it’s universal and not because it’s idiosyncratic, but because it’s specific to a thinly sliced layer of life lived on a particular street in a particular season in a particular body.

“Lot,” the title story, is no exception, and is perhaps the most place-resonant in his debut collection, the characters at once clinging to their piece of land and disavowed of it such that the situation feels like an emergency no one’s noticing. It’s in this double-state that we find our unnamed narrator, the lone child left to help run the family restaurant in Houston’s swirling East End. His father has split, his sister has married out, his brother is stationed overseas, and his mother is under pressure to sell as the neighborhood gentrifies. That specter of gentrification—in food, in love, in money— pushes up through the family’s life like the disruptive roots of a live oak.

“Change anything too much, and it gets harder to keep it alive,” our narrator says, a warning to his mother about evolving into something else. “Lot” is part of a constellation of connected stories that span this collection, a kind of epic in episodes. At this point in the narrator’s life, the explosive potential of change tremors under his surface, in both his body and mind. The consequences of acknowledging the slow cracks in his life are massive, but “Lot” deals with those fissures with a high-wire combo of precision and tenderness.

And it’s that combo, Washington’s restrained but unctuous writing, which reliably knocks me over. This narrator never overstates or wallows in description or nostalgia. He lives a life of held breath, practicing an economy of emotion in a world that could—that does—slip away and away. But his words and thoughts still cut. There is a memory the narrator has of Javi, his gone-away brother, teaching him to hit a baseball in the yard. It’s one lean memory that tells us everything about everything. As day grows to night, Javi stays with the memory and, “with the moon whistling and the cars in the road and the grass inching beneath us like caterpillars.” This is the place we’re given, his lot, one where even the grass is threatening to leave.

But you want to stay. So you end up looking hungrily at the margins and in the dark and through the streaked window. And that’s when you end up seeing the whole goddamn place.

– Aja Gabel

Author of The Ensemble

Remember This: Love Is a Verb

Bryan Washington

Share article

“Lot”

by Bryan Washington

Javi said the only thing worse than a junkie father was a faggot son. This was near the beginning of the end, after one of my brother’s marathon binges; a week or two before he took the bus to Georgia for basic training. His friends carried him home from the bars off Commerce, had him slinking around Houston like a stray. Since Ma had taken to locking the door at night, it was on me to let him back in.

At first, she hit him. Asked was he trying to kill her.

Was he trying to break her heart.

Later on she took to crying. Pleading.

Then came the clawing. The reaching for his eyes like a pair of stubborn life rafts.

But near the end Ma just stared at him. Wouldn’t say a word.

Javi sat on my bed when he told me this. Smelling fresh like he’d just been born.

I asked what he meant, and he looked at me, the first time I think he’d ever really looked at me before.

He told me it didn’t matter. It wasn’t important. He told me to go back to sleep.

2.

Ma planned on leaving the restaurant to the three of us, but then Jan had her own thing going on, and she didn’t want shit to do with the business, and Javi deployed, and it all came down on me. So I stayed. I slice and I marinate and unsleeve the meat. Pack it in aluminum. Load the pit, light the fire. The pigs we gut have blue eyes. They start blinking when you do it, like they’re having flashbacks or something, but after nineteen years of practice one carcass just feels like the next.

Way back when, Ma made Jan responsible for that, for prepping the beef with paprika and pepper, for drowning the carp with the rest of our voodoo, but then my sister met her whiteboy, Tom — working construction in the Heights, way the fuck out of East End — and he stuffed enough of himself inside her to put her in bed with a kid. Which brought our staff to two. Just me and Javi.

Neither of us gave a shit about cooking, but we both cared about eating. Ma had us wrapping beef in pastries, silverware in napkins. Javi taught me how to dice a shrimp without getting nicked. He plucked bills from pockets, cheesing like his life depended on it, and, since he was already nineteen, I followed his lead until Ma finally caught me with the fifties in my sock.

For which Javi took the blame. Ma leered him down a solid ten minutes before she told him to leave, to pack his shit, to go, to never come back. And he did it.

He went.

Joined the service. Sent postcards from brighter venues. Now it’s just me in the back. Packing aluminum in paper bags. Setting the ovens to just under a crisp. Ma pokes her head in when there’s time — the one thing we have too much of — just to ask me if I’ve got it. If everything’s under control.

And the answer’s always, always no. But of course you can’t say that.

3.

Come morning I’m in the kitchen around eight. Ma’s counting bills, twisting rubber into bundles.

Good night? she asks, and I say, Yeah, same as always, Ma.

She’ll nod like she knows what the fuck I’m talking about. Ma learned about suspicion from my father, from lies he’d wooed her away from Aldine with, but then he left for a pack of cigarettes and she gave up snooping entirely.

We don’t talk about where I go most nights or how I get back, ever, so I head to the freezer to handle the prep.

Beef’s fairly quick. Fish too. Chicken takes the longest. We douse them for a week or so — just drown the carcasses in salt. Ma adds her own seasoning, all pepper and grain and kernel, coating every limb with it. Shit she pulled from her mother, and her mother’s mother before her, back when they picked berries in Hanover. Then we stuff it all in some buckets, let them sit for like a day.

It’s something our father would do. He’d pitched Ma the restaurant like a pimp, like a hustler.

Think Oaxaca!

Bun and patties, menudo on Saturdays.

The blacks eat chicken so we’ll have that, too.

And, sometimes, I like to think that she put up a fight back then, tried to think of another plan.

But a month later they’d already set up shop. Found a shotgun off the freeway, polished it up. Our father served quesadillas and wings and pinto beans, hiring any number of the neighborhood layabouts, his friends, whooping and yelping and eyeing Ma from their stations. Sometimes she’d swat at them, ask who the fuck were they working for. Mostly she let them carry on.

My parents smoked cigarettes on the porch at sunset. Waving at everyone like they had something to smile about. But Ma couldn’t get down with his pails. How they stank up the place. She said we were living in a slaughterhouse, that her home smelled like death.

Her kids were another story: Javi and I dipped our toes in the buckets, until Jan saw us, and said to cool it, to cut it out. We kept doing it and she kept catching us.

One time she’d reprimanded us a little too slow. Javi grabbed her, and he dunked her, and he held her until his arm got tired.

Hush, he said, and then again, slower.

4.

Javi sent letters from out east. A photo of some dunes. Some birds. An old fort. White words on gray backgrounds, angled across the card. He’d say how he was doing (fine), bitch about the weather (worse than Houston), ask for more photos of Jan’s kid.

Once, he wrote a letter just for Ma. She wouldn’t let anyone touch it.

Once, he wrote one just for me.

He asked how Ma was doing, really, and about the baby. And about my plans. Said something about sending me some money. About what he’d do when he got out. He told me to write him sometime, that he’d appreciate it.

So I did that. I wrote him a letter spelling everything out. I wrote about Ma, and the shop, and the school. I wrote about Jan and the baby. I wrote about the Latina girls from Chavez I’d been meeting and fucking, and how that wasn’t working out, or how it wasn’t what I’d thought it should be, or that there was something else out there maybe, but what that was I couldn’t tell him, until I saw him, until he came back home.

I actually wrote that down.

I tossed it in the postbox before I could think about it, before it really messed me up.

But then a letter came for Ma, and then another one after that for Jan. But nothing addressed to me. I never tried again.

5.

I spend most days just trying to keep the place from burning down.

Four stoves, two ovens, three sinks. They’re always running. It might actually scare the shit out of anyone who cared to check, but nobody does that with Ma up front, dropping smiles and tossing napkins and asking everyone how their food is.

We get our rush in the afternoon, when the neighborhood shakes itself awake. Same faces every day. Black and brown and tan and wrinkled. The viejos who’ve lived on Airline forever. The abuelitas who’ve lived here for two hundred years, and the construction workers from Calhoun looking for cheap eats. The girls from Eastwood my sister left behind. The hoods my brother used to run with downtown.

Occasionally we’ll pull in a yuppie. They’d find us on the internet, review us in the weeklies. You can tell from the clothes, the bags. Their shades. How they ask what’s on the menu, any specials. Ma would treat them all like God’s children.

It’s a major event in our week, this pandering. So they get all the stops. And they’ll promise to tell their friends, to come back next week, but they sit through their meals with their eyes on the tile and their elbows on their purses so we know they never will.

Ma swears it’s the locals that gut us. That we can’t keep giving handouts.

I don’t know about that though. Change anything too much, it gets harder to keep it alive.

6.

You know the day’s almost over when Jan drops in with the kid. I set the burners to low and pop out to kiss him, and she swats at me, tells me to wash my nasty hands. Ma’s chatting with the only table occupied, a gaggle of off- duty fags, dressed down.

Ever since she had the baby Jan’s been dressing like a nun. Black sleeves. Dresses. The phone company lets her do whatever she wants — because she can enunciate — but if she’d laced those buttons from the beginning she wouldn’t be scrounging in the first place.

She talks with Ma while I play with the boy. He’s like a sack of potatoes. Fat in the face. There’s none of me there, which is fine, but what makes him even luckier’s that there’s none of his daddy either.

Jan leans across the counter, says things are looking slower. I tell her we’ve seen worse.

Any worse, she says, and there’ll be nothing to see.

It’s how she’s started talking. Between moving downtown, and living alone, and wilding out and fucking around and ending up with the whiteboy, Jan was the black sheep after she’d gotten hitched, almost as bad as Javi once he’d enlisted. Once the ring hit her finger, she swore the rest of us off. She was always dropping by Next Week, always tied up with the in-laws; until the day she finally brought Tom around the restaurant for lunch, and he laughed at Ma’s jokes, and he actually asked me about my life.

But after we ate, and her guy took off for home, Jan called us both trash. She said we’d embarrassed her. We were the reason she never came around. And Ma didn’t even blink — she just said, Go.

But a baby makes everything better.

I ask if Tom’s found another job yet, and she tells me he has, a construction gig down in River Oaks. For some billionaire apartment complex by the Starbucks.

So you should have a little extra to kick around, I say. For Ma.

We both look at the kid.

Mom’s fine, she says.

Ma’s broke.

Business in a place like this, and you’re hot about being broke?

You’re the one who said it was slow.

Trust me, says Jan. Or her, at least. She’s got a plan.

A plan.

Property value’s going up, she says. I saw at least two new buildings on the drive over. And some new families in the neighborhood.

By new she means white. We don’t even have to say it anymore.

I tell Jan if she thinks we’re selling our place, she’s who’s fucking crazy.

Yours, she says. Or hers?

Ours, I say, and my sister hums that right off, staring out the window.

But anyways, she says. How’s the queer thing going?

It’s going, I say.

Any prospects?

Stop.

I have to ask.

No one has to say anything.

Jan just shakes her head. She’s the only one who talks about it. I don’t know if Ma told her, or if Jan just put two and two together, but one day she told me it didn’t matter who I was fucking. Out of the blue. She said it wasn’t her business, or Ma’s business, or anyone’s business. She said that Javi never asked for permission. I shouldn’t have to answer to anyone.

But she always, always asks. And I give her the same answer every time.

We watch her kid. He’s still running in circles, trailing his hand along the counter. When he makes it to the boys by the window, they squeal.

They’re all done up. Hair the shade of supernovas. Out of the four of them, three are obviously fucked; the other one’s just a little too thick, touched with a shade of after- shave. He’d look like an imposter if he weren’t clearly the leader; when Jan’s kid stops in front of him, he lifts him by the armpits.

The others squeeze his cheeks. Run their fingers through his hair. They’re all in sandals, heels slapping like crocodiles. The kid’s soaking them up, taking it in. And the fags are, too — cooing, like birds, urging him not to grow, grow, grow.

7.

Couple months before he started to turn, Javi got it in his head that he’d teach me to sock a baseball. This was before Jan’s baby, and the military, and the neighborhood’s infiltration by money, but after my father left, a time when you could probably look at the four of us and still call us okay. It would’ve been summer, because he slugged me in my shoulder, said we were going outside, to get my ass off the carpet and take notes on being a man. I was watching a movie, Princess fucking Mononoke, and he told me I had till he counted to one.

I couldn’t hit for shit. Didn’t matter that it was dark out. Woofed it even when he stood in front of me, pulling his elbow back just in time.

Useless, he said, after every single shot. You’d spill a water bottle if I put it in your mouth.

But he stayed out there.

He didn’t tell me to kick rocks. Didn’t deem me obsolete. Didn’t manufacture an excuse to disappear. Didn’t knuckle me in my ear until blood came out. All that would come later, like he was making up for lost time. But that night, he stayed with me, with the moon whistling and the cars in the road and the grass inching beneath us like caterpillars.

Again, he said, shaking his head, squeezing my shoulder.

8.

The evenings I’m not out chasing ass I’m across the sofa from Ma. We’re on the second floor of the property, this joint we used to rent out after Jan left.

Halle Berry’s on the television. Boxing the hell out of some kid. It is cable and it is senseless, but I laugh when Ma laughs, turn sober when she tears up.

By the end of the movie she’s finished her tea. She’s looking over the commercials, past the credits, through the wall.

Ma, I say, and it spooks her.

She looks at me.

My mother’s the only girl in the world who smiles as sad as she does.

Just thinking, she says.

When I ask about what, she says the future.

Your sister and the baby. Your education.

And the restaurant, I say. When she makes her I-don’t- know-why-you’d-say-such-a-thing face I say she’s my mother, that I’m no dummy.

The moment Javi left, she’d started pushing me toward college. Asking about homework. Meeting with teachers who couldn’t have given a shit. And it didn’t help that I couldn’t care less either; that, in the grand scheme of things, I knew this wasn’t helping anyone.

Except eventually I changed my mind.

I thought about Rick and the rest of them. I can’t even tell you why.

And, eventually, my counselor started looking me in the eyes. I still worked the kitchen, but Ma filled in the gaps, covering for me, or hiring the stove by the hour, until I finally got the diploma and she cried at graduation and it became clear that the only place I was going was nowhere.

Money issues aside, leaving the neighborhood meant leaving the shop. Which meant leaving Ma. Leaving her broke and alone. She used to wave this off, tell me Jan was still around, but I grew up with my sister and there’s things you don’t forget. I even tried community college for a week or three, right on Main Street, sat in the front row and everything, but one day I stopped all that and no one said a fucking thing. No alarms rang. No one called the restaurant. It didn’t take long to see that there’s the world you live in, and then there are the constellations around it, and you’ll never know you’re missing them if you don’t even know to look up.

Ma’s daughter had left her.

Her son had left her.

Her husband had left her.

So I couldn’t leave her.

Not that it’s worth feeling sorry for.

It’s honestly not even sad.

They’re only inquiries, Ma says, after a while. The neighborhood’s changing.

It’s always changed, I say. It’ll keep changing.

I’m weighing our options. We might need the money.

My ass, I say. For what?

Watch it, she says.

You know, she says, but that’s all she’s got.

Ma just starts nodding. Moves her head like she’s already made her decision, but she’s still willing to hear me out, at least for a little while.

Months after our father left, Ma sat Javi and me in the kitchen, something she never did. Hair all over her face, in last week’s nightdress, she looked like Medusa in the pit.

She said if we remembered nothing else she taught us, to know that love was a verb. She had makeup all over her brow. Smears of it on her lips.

When I’d started to open my mouth Javi kicked me under the table. Didn’t even change the look on his face.

It is an active thing, she said. Something you have to do.

But now, when she shuts her eyes, I know she’s not asleep. I watch until her breathing slows.

Until I know she’s finally out.

Turning a Passion for Classical Music into Fiction

9.

This next time I’m ready when the realtor shows. Ma’s so caught off guard she doesn’t have time to lie.

It’s actually a lady. Korean, probably, but I’m not the one to know.

Well, she says, smiling at me, but talking to Ma. If this is a bad time —

It’s a great time, I say, taking the chair beside Jan. She doesn’t even glance at me.

Ma says something about the afternoon rush, but once it’s clear that I’m not getting up for anything the suit-lady smiles, dives back into her spiel.

It hurts me to say she was good. Told us who was interested, how much we’d profit. Every now and again, she’d add a quick but, as if to show us she was the only person worth trusting here, our only honest apple.

And once she told us everything, she asked if we understood, did we have any questions.

And since none of us wanted to be the one to ask them, she stood, and she smiled, and said it was nice to finally meet me.

She nodded at Ma and then Jan. Told us all to stay in touch.

We told her we would.

10.

When our father split, he took every sound in the house with him. Ma wouldn’t talk for another few weeks, at least not to us; so the last things she’d called him were what floated in the air.

Javi and I took note, but we weren’t actually worried. He’d left before. They fought, he’d take off, but he’d always materialize by Sunday, frying eggs over salsa on the stove, Beatles wailing on the radio.

But Jan told us that this time was different. That she’d actually talked to him the night he left. She said he called her sometimes, when everyone was asleep. Javi said he knew she was lying because who the fuck would waste their minutes on her, and she looked at him, and she smiled, and she said we’d never see our father again.

When I asked Javi if there was any truth to this, he didn’t say anything. He was usually the first one to pop off, calling bullshit even when he knew better — but he just put his hand on my head, and he told me to be tough. That it was the only way a man did things in life.

So I stayed up to see if it was really true. Javi’d already started sneaking out by then, and when Ma caught me by the phone that night she just blinked.

Then it finally did ring.

An alarm went off in my eyes.

I pounced on it, already asking where he’d gone, and when he’d be back, talking and talking, words bursting out of my nose, my ears, but of course it was only my mother’s brother, asking who was this, where was Ma, get the fuck off the phone.

11.

I tell Ma that selling the lot is a bad move. We’ve closed shop for the evening, and the sun bleeds through the windows.

Nothing’s been decided, she says, and Jan says Ma doesn’t have to do that, she doesn’t have to lie.

It’s done, Jan says to me now. It’s been done for a while.

I tell my sister to shut her mouth, to crawl back into her hole.

Hon, says Ma.

Let him, says Jan. Let him have his say.

Because the sale went final a week ago, says Jan. We’ll be out of the building in two weeks at most.

We, I think. I look at Ma.

She doesn’t have to explain it to you, says Jan.

Ma, I say, and she stands up to go, and I know I should follow her but I sit my ass down.

If I tell you what I think, will you listen? says Jan. She’s still at the table, knuckles under her chin. Will you be serious for two seconds?

What you think, I say.

Yes. The conclusions I’ve reached with the data we’ve acquired.

Tom’s got you thinking now? You’re the barrio’s new psychiatrist?

Let’s start with that, she says. You think you’re special. You think you’re special since you live where you live, but no one else in this dump really gives a shit about you.

Bravo.

You think if you don’t say anything about it, this place will just stay how it’s been. You think that’s a good thing. You think it means you won’t have to change.

You think, says Jan, that he’s coming back. Like, if we all stay in place, he’ll stick his head up from six feet under. We’ll just rewind everything. Click him back into rotation.

But here’s the thing, she says. Javi’s not coming back. Javi’s not here because he’s gone. Gone. And as soon as you pop your little-brother bubble, and you actually look at —

And this is why we should sell, I say. That’s your reason?

What reason, she says.

Because you didn’t fucking like him. You never fucking liked him.

Jan frowns at this. She folds her arms. It puts another thirty years on her.

No, she says. We should sell because your mother needs the money. Because neither of us has it, and the neighborhood’s buying out.

Just her, I say. My mother? You think she won’t give half to you?

She reaches across the counter to put her hand on my cheek. Massages it, one finger between the other.

I wouldn’t take it, she says.

I wouldn’t want it, she says. Because you two need it. You need it.

But if you can think of a better way to fix this, she says, you need to tell me. Right now. You need to speak up.

Jan fondles my face. I can feel it burning. It’s been years since my sister touched me, let alone with warmth.

Her fingers are sharp. A little callous.

Get out, I say.

Ah, says Jan. You’re mad.

We’re closing shop, and I’ve got dishes to wash. And you smell like vomit. Get out.

My sister looks me over like she’s deciding something. Fine, she says.

But you need to start making plans, she says. You need to figure out where you’re staying next. She’s getting older, and I’ve got a full house, so you’re damn sure not living with me.

The nickel I throw skips over the counter, across a tabletop, right by some silverware, and into her palm.

Don’t ask me how. I’d meant to hit her in the eye.

But she catches it, and she smiles, again, and she slips it in her purse on her way out the door.

12.

Javi was dead for a month and four days before his first sergeant made it out to the restaurant.

I don’t even remember what I was doing, but Ma met the guy at the register like any other customer. She had no idea.

This is what kills me, more than anything else.

Dumb luck, is what his sergeant called it. A car crash on post. Only he said it like it really was dumb. Completely illogical. The stupidest thing he’d ever heard.

When Ma asked him to sit, he told her no, he really had to go. He’d just wanted to come by. To tell her personally. Ma asked if he wanted anything to take with him. He said no, he really did need to leave. She told him anything on the menu, anything up there, it didn’t matter what, just tell her and she’d fix it for him.

I don’t know what he said to that. I haven’t gone and asked. But what I do know is that he ended up leaving with nothing.

Jan came over that night. She left the baby with Tom.

We closed shop for the rest of the week, had the funeral that weekend. Tom and his folks showed. Some of Ma’s friends were there, overdressed like toucans in too-tight dresses, crying in heels and mascara and polish. A handful of Javi’s boys made it out, a couple of guys in uniform. One of them asked me if I was his brother. He shook my hand.

Ma just stared at the casket. I thought maybe she’d kick it or push it or pull out her eyes, but she did not.

Two weeks later, doors were back open. Jan told Ma to stay off her feet, but our mother said that wasn’t necessary.

And anyways, it wasn’t possible. We honestly couldn’t afford it.

13.

The day we sign the lot away, Jan comes straight from work. Ma’s in a seat by the window, lost in this dress I’ve never seen before and haven’t since. She asks if I want to stay awhile — to look over the numbers myself — but I say no thanks, I’m fine, let me know when you’re finished.

14.

I used to think my brother would come back at night, like he used to, only this time he’d be dressed like some hijo de papi, like someone with a mother and a sister and a brother he loved. He’d have a wife by then. Somebody with a laugh. And he’d blush when he introduced us, pointing out the house’s trinkets, the floors he used to sweep. They wouldn’t have a kid yet, but it’d be on the way, and when Ma asked him who’d watch the baby he’d look at me, nod, squeeze my shoulder. Say, Who else.

He’d really know me by then. He’d know who I was.

But Javi did come back on leave, once, a few months before that final deployment.

Ma closed the restaurant for the weekend. Rushed around the place making sure everything looked right — that his room was in order, that the cabinets were clean, redusting and revacuuming and all the shit we usually ignore. Jan told her to settle down, that it was Javi, not Jesus, but Ma told her to shut up. One of the only times she’s let my sister have it since the baby.

You take care of what’s yours, was all Ma said. They may leave but when they come back you take care of them. He took a cab from the airport. Let himself in. Hugged Ma and she instantly started to cry. We did the handshake thing. He kissed Jan and he shook her husband’s hand and he snatched her baby up from the carpet so fast that everyone flinched a little bit.

Javi looked thicker. Darker. Not gruff or monosyllabic or any of that shit, but there was something there that wasn’t there the last time we’d seen him. Or maybe something that wasn’t there at all.

We made his favorite dinner, jerk shrimp with potatoes, and he tried to jump in the kitchen but Ma told him to stop playing.

For finally being home, it felt like the end of something. After dinner, he stood up. Yawned. We’d have him the whole weekend, he said, but the flight had been long. He was tired. Ma told him to get to bed, quickly, we’d see him in the morning, and before too long I followed him upstairs, left Ma and Jan in the dark of the kitchen.

My room was his room. I knocked before I went in. Javi’d collapsed across the mattress, away from the door, and he smiled when I touched him, when I took the floor beside him.

Well, I said. I didn’t finish my sentence and he didn’t follow up. We sat next to each other, just being brothers.

After a while, he said I’d grown up. Gained some weight in my face.

I’m fat, I said, and he said no, just a little weight, which was what I’d needed, and the hand he put on my shoulder felt like brambles.

We sat there for a while.

I wrote you a letter, I said, like in those fucking movies.

I know, said Javi.

And then he shut up.

Okay, I said.

So how was it over there, I said.

He didn’t answer. And it was so long before he said something that I figured he’d forgotten me.

It was just another thing to do, he said, in a different place. It’s like I could’ve just stayed in East End.

But you see how other people live, he said. And you really can’t help them if they don’t want it.

That’s one thing I’ve learned, he said. That’s what I’ve gotten out of this.

And it looks like nonsense now, like Santa Claus when you’re older, but that’s when I told him I’d been sleeping with boys.

I told him about the one from the library. About the one from the coffee shop. I told him these things, how I’d tried it with Cristina and Maribel, with LaShon and her sister; and how it hadn’t worked, with any of them, even when they’d stared me down, arms crossed. I watched Javi’s face for something to click or contort or scrunch itself into oblivion but it did not. It didn’t happen.

He said nothing, and I was finished talking. And I didn’t feel it when he slapped me.

I saw his palm coming, but didn’t know it until my shoulder hit the ground, until I looked up to see him staring.

And the thing that I remember about my brother, clearer than what he wore on the day he left, or the cracks he made about our uncle when he came to visit Ma, or the way that he laughed or the color of his eyes or his scent or his funeral, is the look on his face while I lay on the carpet.

When he didn’t get up, and I didn’t get up, I rolled myself over, made a pillow on the floor, and my brother, here and gone, fell asleep on my bed.