Books & Culture

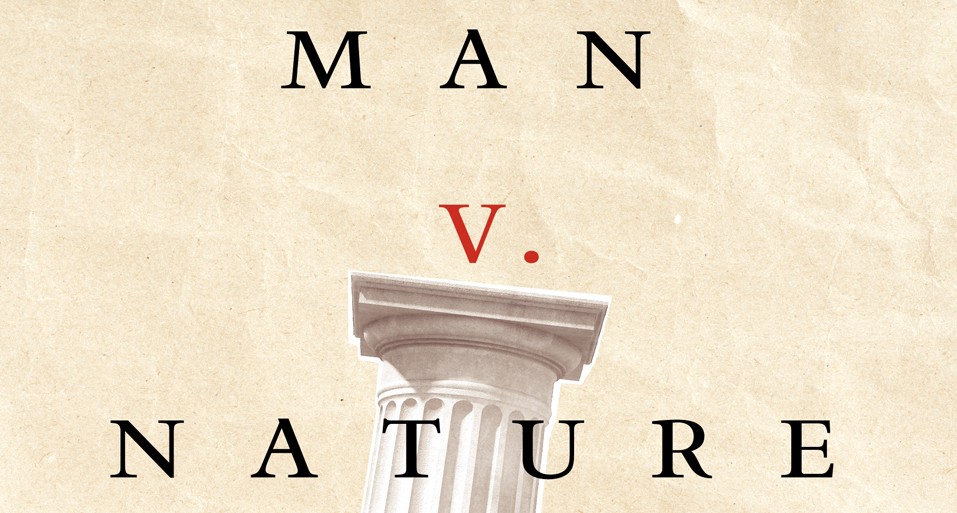

REVIEW: Man V. Nature by Diane Cook

I’m not sure exactly when the current wave of apocalyptic literature began or if it’s ever stopped or if there’s even the possibility that it will lessen or plateau before this planet reaches its end, but I haven’t read anything that tackles the anxiety of oblivion better Diane Cook’s Man V. Nature.

To be clear, Cook’s debut collection isn’t exactly apocalypse literature in the same category as the recent wave of world-ending books. Those stories tend to feature a recent environmental or political calamity — the coasts are flooded or the whole country is bombed out and bleak. Survivors are hunting deer, welling for water and staring into black nights, remembering the dead. They’re wandering, like in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, in search of necessities and a will to live. And yet they still have the same relationship woes and dysfunctional families they’ve always had — Apocalypse Survivors: They’re Just Like Us!

At their worst, these stories can be either deeply moralizing (Left Behind, I’m looking at you) or just pure destruction porn, an outlet for our deepest anxieties about global warming or the human tendency toward war. This isn’t to say that these sorts of books aren’t often insightful, brilliant or at the very least entertaining, but they tend to fare better when they focus on how we survive after the dust settles than the oblivion itself. Emily St. John Mandel’s recent novel, Station Eleven, is a perfect example of this, focusing on the needs that lie just beyond basic survival — the love and stories chief among them. In The Road Cormac McCarthy uses a hellish landscape as a kind of neutral background so we can see the life of his characters in high relief. Yet the frames of these stories, an aggressive flu epidemic and a total nuclear annihilation, still read like possible ends to some of today’s headlines or thirty other books you’ve read. The tropes of the apocalypse are hard to escape. There may be more than one way for the world to end, but it tends to somehow feel the same.

The literature of the apocalypse can offer so much more than sheer anxiety fulfillment. At its best, these sort of books can let the reader grapple with the intangibility of total oblivion. Man V. Nature passes up the stock set pieces and gnaws on that thematic bone. The world doesn’t end so much as people’s worlds end — their senses of safety, their long-held narratives, their relationships and ideals.

Often these ends come at the hands of a shadow-y force, a system that is just beyond the comprehension of the people it controls. Something like a government, but not quite. Something like nature, but not quite.

In Moving On, a woman who has been recently widowed is taken from her home and forced into a prison-like women’s shelter. Heartbroken but timidly optimistic, she’s encouraged to demolish the memory of her late husband and take homemaking classes before a new man shows up to select her like a pound puppy. Cook creates a surreal but painfully honest world. She’s not trying to create a possible dystopia; instead she dramatizes the private catastrophe of losing love and the impossibility of escaping memory, despite what others insists.

Moving On is also one of the stories in the collection interested in womanhood and manhood. Here, a single woman is seen as just a husband-less wife, a poisonous societal pressure that the real world is still far from shaking. In another story, Marrying Up, there’s an unspecified violent uprising surrounding the apartment where the narrative unfolds, but it’s the interior of the home that is really terrifying. After two sweet but unimposing husbands are destroyed by the mob, a woman marries her Hulk-like neighbor purely for his size and brute protection. “Making love felt like getting run over. I was pancaked like in cartoons.” But eventually it is her own need to be protected that destroys her; after she gives birth to a monster child and her husband becomes increasingly violent. Gentleness no longer has a place in the world.

Cook is a pro at using the bizarre, sometimes even fable-like set ups to upend our most essential fears. Somebody’s Baby, a twenty-page stunner, unraveled the particular terrors of parenthood and expectant parenthood with a plot that was both utterly strange and completely familiar. Almost every time a newborn is brought home in this neighborhood a silent man stands in the yard, sometimes for months, waiting for the right moment to rush in and steal it. Of all the neighborhood’s mothers, only one is appalled by this tradition and after two of her babies are stolen she hunts him down and discovers all the stolen children who have grown ambivalent about their former families. It’s a beautiful distillation of the way parental fear changes shape: it starts as a terror of losing this vulnerable, tiny thing to some sudden death, then morphs into the worry that your child will become a stranger to you — someone you no longer recognize or someone who no longer recognizes you.

A handful of the stories wrestle with the antidote to annihilation — sex. In It’s Coming some mysterious, minotaur-like monster is rampaging an office building, eating workers by the handful. Two co-workers, inexplicably turned on by their final moments on earth, begin groping each other as they run from the beast, eventually fucking themselves into doom. In another, Meteorologist Dave Santana, a woman is driven witless over the one man she can’t seem to sexually conquer: Meteorologist Dave Santana. It was also the funniest story in the book and had one of the truest endings, one with a perfectly deft revelation that elevates the farce with wisdom.

When Cook does venture into a more traditional apocalyptic setting she does so with Barthelme-level absurdity, as in The Way the End of Days Should Be. A man is living luxuriously in the aftermath of massive natural disaster; he has plenty of food, a secure home, good wine, even scotch though he stays sober. Lonely, he eventually takes in a man who arrives at his door, starving and weather-beaten. A dilapidated home across the street, packed with survivors and low on supplies, has made him wary of outsiders, but he needs the company to survive and his particular distortions of this need propels the story.

In the final story, The Not Needed Forrest, “the State” determines that some ten-year-old boys are simply unnecessary, takes them from their families and throws them down a chute. Most perish in an incinerator, but “fourteen boys, naked and shimmering with mud” escape through some accidental portal that deposits them in a forrest. They find a camp and rejoice in their newfound freedom, living as violently and noisily as they want. “We’re boys. We’ll stun a bird and twist its neck, and we’re on to the next thing…We collect bird eggs, and we eat the mom.”

Winter arrives. The food runs out and starvation sets in. When one of the boys dies in an accident, the rest hesitate, then cook him. Eventually they start killing each other for food based on a lottery system, turning from tender to murderous in a span of two pages. Though the original enemy seems to be the cruelty of winter, by the end of the story the match has turned from Boy V Nature to Boy V Boy. Human cruelty is the greater threat.

Because our eventual ends are an essential human preoccupation, apocalypse literature has never been and will never be a trend. It’s always being written. We’re endlessly interested in the worst-case scenario, not just for the whole world, but for our personal worlds. A near-death experience can be the moment of redemption and rebirth that a life has been waiting for. Apocalypse books can have a similar function — to reveal what is essential about humanity after the worst, reminding the reader of what is most valuable in the world. But I prefer Cook’s approach, extracting and distorting a sense of oblivion without using environmental calamity or a surreal police state as scaffolding. Unfortunately we’re getting plenty of that in the news.

Enjoy a look at Man V. Nature: click here for issue 125 of Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, as recommended by Terry Karten, Executive Editor, HarperCollins Publishers

by Diane Cook