Books & Culture

REVIEW: The Age of Movies, Selected Writings of Pauline Kael

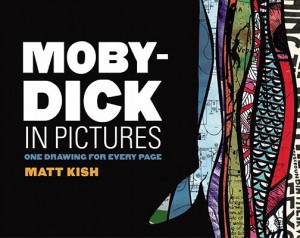

The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael

Pauline Kael

Library of America

750 pp / $40

The sad implication in the title of this selection of writings by the late movie critic Pauline Kael is that the Age of Movies has passed, that movies matter less than they used to. The big screen, after all, has been supplanted by a variety of little screens (the television, the computer, the smartphone), screens that we use to watch grisly traffic accidents, celebrity bloopers, cute kitten videos, and occasionally even movies.

If one thing is certain, it’s that no movie critic will ever again matter as much as Pauline Kael, who reviewed movies (Kael dismissed the words ‘film’ and ‘cinema’ as stuffy and elitist) for The New Yorker from 1968 to 1991. She was read avidly or fearfully not just by moviegoers but by filmmakers and fellow film critics. She was caricatured in movies and comedy shows; her spats with other critics were cultural front-page news.

Kael wrote in an intimate, garrulous, slangy manner that is natural only to a writer who is confident of a large and enthusiastic audience. When she praised, it was often in the tones of a ravished lover and when she scolded it was if she were personally offended. What she wrote about, elaborately and brilliantly, were her own gut reactions — her favorite word was probably ‘visceral.’ What literary critics call the affective fallacy — which means judging the worth of a work of art chiefly by its emotional effects on the viewer or reader — was the basis of her critical approach.

Kael died in 2001 and published almost nothing except movie reviews; by all rights, her reputation should be in eclipse now. Yet in the past ten years, we have had a selection of her table talk; Sontag & Kael: Opposites Attract Me by Craig Seligman, a Compare and Contrast exercise/valentine to Kael and cultural critic Susan Sontag; a full-length biography; and now, from the Library of America, the publisher of Melville, James, and Faulkner and the closest thing to an official arbiter of our national literary canon, this collection of movie reviews.

In one of the earliest pieces from The Age of Movies, Kael writes about the overwrought, pseudo-balletic dancing in the movie of West Side Story

What is lost is not merely the rhythm, the feel, the unpretentious movements of American dancing at its best — but its basic emotion, which as in jazz music, is contempt for respectability.

Contempt for respectability was also the basic emotion behind many of Kael’s reviews, especially when she started out in the late ’50s. During that era the respectable was a much more formidable opponent than it became towards the end of her career: the Catholic Legion of Decency still issued a list of forbidden films, Ulysses and Lady Chatterly’s Lover were still banned in this country and there was a blacklist in the New York Times against all art that mentioned homosexuality. Kael came out of the San Francisco experimental art scene at a time when it was a real, thriving bohemia, and her ultimate term of contempt was ‘square.’

If there was anything that Kael hated, it was the big, solemn, ‘message’ picture that attacked some important problem like nuclear war or race prejudice or the inequities of the legal system. Kael loved vulgarity, but she hated obviousness, especially in the form of the received ideas of the middlebrow picture. About The Verdict, she acidly notes about the inevitable redemption of the disillusioned Paul Newman character at the end of the movie, that he is ‘reillusioned.’

Kael was fortunate to reach her prime as a critic in the late ’60s through the mid-70s, in an era when American movies were coming into a second renaissance. More than any other movie critic of her era, she articulated what was singular about the group of maverick directors which included Coppola, Scorsese, Cimino, Peckinpah and others who were transforming the Hollywood studio system.

In her penetrating review of The Godfather, she wrote:

If ever there was a great example of how the best popular movies come out of a merger of commerce and art, The Godfather is it…

When ‘Americanism’ was a form of cheerful, bland official optimism, the gangster used to be destroyed at the end of the movie and our feelings resolved. Now the mood of the whole country has darkened, guiltily; nothing is resolved at the end of The Godfather, because the family business goes on…The Godfather is popular melodrama; but it expresses a new tragic realism.

Kael had a powerful descriptive imagination that made a lot of the movies she championed, especially in the second half of her career, seem more interesting than they actually were. It’s hard nowadays to understand what she saw in Last Tango in Paris or Convoy or Blowout.

Writers are usually difficult and suspicious loners, stingy with help and encouragement. The extroverted Kael, more than most writers, was both generous and shrewd in nurturing and promoting young talent. Part of the reason for her continued prominence after her death is that many of her protégés are now important players in the cultural establishment.

But Kael’s writing has a wider significance as well. When she started out, the model for most critics was the high-minded, self-effacing and Anglophilic literary criticism of T. S. Eliot. Kael reaffirmed the importance of the quirky personal voice and the supremacy of the gut feeling; elevated the autobiographical and the anecdotal as key evidence in the critical argument; and invited popular culture to be an equal player with high culture. There is scarcely an American critic around who hasn’t been influenced by her, directly or indirectly.

The quality and texture of Kael’s writing is more important than the accuracy of her often dubious judgments. She did for criticism what Bellow did for the novel — she gave it an American voice.

The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael

by Pauline Kael

***

— John Broening is a chef and writer based in Denver, Colorado. His work has appeared in the Baltimore Sun, the Baltimore City Paper, Gastronomica, Edible Front Range, and the Denver Post, for whom he writes a weekly column about food.