Interviews

What’s More American Than Erasure?

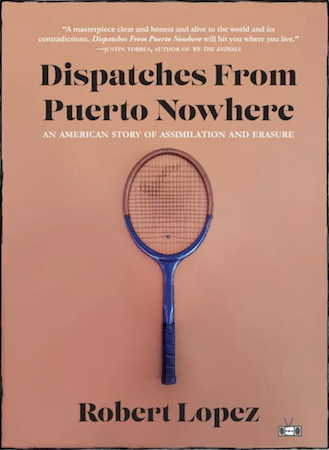

Robert Lopez's book "Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere" explores the loss of his family's culture and language

A century ago, Robert Lopez’s grandfather Sixto left Puerto Rico for Brooklyn. Puerto Rico would have been a U.S. territory for decades at that point. “In theory, Sixto wasn’t an immigrant,” Lopez writes in his new book Dispatches From Puerto Nowhere: An American Story of Assimilation and Erasure, “but of course he was.”

Dispatches from Puerto Nowhere is a collection of short essays illustrating the ramifications of assimilation and the way amnesia, at any scale, is difficult to see until it’s not, at which point you see it everywhere. “What’s missing isn’t just part of the story,” Lopez tells us. “It is the story.”

Lopez’s nonfiction debut is simple in form but chock-full of complexity: his fragmented family history is sprinkled with loss and longing and parades and boxing bouts and tennis matches and myths and misquotes and vaporous memories. Lopez feels his lack of family lore is something fundamental he is missing, not unlike proper tennis footwork, though he manages to compete without it. “Maybe I’d have a better forehand if I spoke Spanish,” he quips.

In telling his family’s story, Lopez is, in some sense, telling this nation’s story. The history of the United States is brimming with erasure—both actively (a founding dependent upon displacement and genocide) and passively (in terms of what’s left out in the stories we tell). “That I was born Puerto Rican was happenstance, but that I have no connection to what it means is no accident,” Lopez concludes. Put another way: What’s more American than forgetting?

Lopez and I connected to discuss assimilation, language, sports, and American culture.

Alyssa Oursler: In Dispatches from Puerto Nowhere, you chronicle your family’s “successful” migration and assimilation to the United States while reflecting on all that was lost in the process. Why is “successful assimilation” an oxymoron—and why did now feel like the time to write a book about that fact?

Robert Lopez: Assimilating into an adopted culture is the proper and respectful thing to do unless the assimilation includes some sort of repudiation or denial of one’s native culture and identity. One should try to assimilate if one decides to live in another country. Why choose that place unless you’re interested and invested in the language and culture of your new home? This should apply to everyone in every direction. But one needn’t deny the heritage left behind.

The book was started during the last administration and their draconian immigration policies. And then seeing the response to Hurricane Maria …. Well, if not then …

AO: I feel similarly that a part of my identity was lost in the language and culture that was not passed down to me—my grandfather was a war refugee from Ukraine and while my mother grew up speaking Ukrainian, she has since lost the language almost completely. But in a white supremacist country, assimilation with white skin is undoubtedly different. In the book, you’re grappling with being forced to assimilate in a country in which you are still not fully accepted. What do you think people overlook or misunderstand regarding the relationship between race and assimilation?

RL: I’m not sure I’ve ever felt or said that I’m not fully accepted in this country. Maybe I didn’t pay close attention and missed instances of that lack of acceptance, but I’m not complaining about how I’ve been treated. Latinos whose skin-tones are a little darker and speak English with an accent or not at all, they’re the people who have had a hard time here in the United States.

Every newcomer is or was an “other” at some point and all “others” have been ostracized in this country. No Irish need apply and so forth. Whether the “other” is based on religion or skin color/ethnicity or sex/gender/orientation or what have you, Americans don’t take too kindly to the “other.” Of course, the “other” has a hard time all over the world, so it’s not only an American phenomenon. So, we may call this country “white supremacist,” but so is every other “white” country in the world, to one degree or another. And the same is true for every country that isn’t white and who reigns supreme in those places. “Racial purity” has been going on for centuries all over the world and some of the most egregious examples of this can be found in Japan, Korea, China, for instance. The same goes in Africa and the Middle East. All one has to do is Google ethnic cleansing and you’ll have quite a lot to read.

AO: You discuss police violence in the book. While your friend who was killed by police was white, I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the relationship between racialized police violence and assimilation/erasure.

RL: Of course, racialized police violence is heinous and a problem that needs to be addressed. But when we focus too much on race, we’re missing the overarching (fixable) issue in play here, which is the militarization of police throughout the country. The cops who beat Tyre Nichols to death in Memphis were all Black, too. Was there a racial component in this case? Perhaps. Perhaps, though, too many cops and the culture of “policing” in this country is the problem and we need to get rid of them and replace them with a new breed of police who are trained to actually protect and serve communities rather than brutalize and kill people. Calls to “end racism,” while well intentioned and a worthwhile goal, are futile. It’s like saying “end stupidity.” There’s no way to accomplish it.

Every newcomer is or was an ‘other’ at some point and all ‘others’ have been ostracized in this country.

We thought we made tremendous, groundbreaking, trailblazing strides when we elected President Obama. But look how far we’ve regressed in the wake of his presidency. How low we have sunk. It’s more than disheartening and the future is bleak. Nothing is likely to change in this regard, but in theory we should be able to get rid of brutal cops and replace them with the sort of people who aren’t looking for opportunities to beat, choke, or shoot people.

I don’t know if any of this has to do with assimilation or erasure.

AO: You offer several pointed, albeit brief, descriptions of the whitewashed suburban spaces you were raised in. How do you think the physical reality (or, in your words, “architectural atrocities”) of the suburbs encourages and/or depends on erasure?

RL: The strip mall is all about convenience and so much of our American life is about convenience. Aesthetic beauty or beauty of any kind doesn’t play a part in our day-to-day lives. All of these spaces and these attitudes promote and propagate a homogenous culture wherein we all become the same regardless of our disparate backgrounds. We’re all consumers. So, even if the strip mall has a Mexican restaurant next to a Middle Eastern restaurant next to a barbeque joint, it all feels the same. One would think there would be an acceptance or celebration of the individual cultures inside these places, but that hasn’t been my experience. The erasure is everywhere in the suburbs of New York City, in particular.

AO: Why did the term nuclear family confuse you as a child?

RL: I thought it had to do with nuclear war.

AO: I can see that. I threw myself into basketball as a kid, I think in part because it helped me fit in with my own nuclear family and because it helped me make friends—though neither of those were conscious calculations. What first drew you to the sport of tennis?

…when we focus too much on race, we’re missing the overarching (fixable) issue in play here, which is the militarization of police throughout the country.

RL: I always appreciated the game. You get to run around in short bursts and hit the hell out of a ball. You get to play offense and defense. There’s so much strategy when it comes to tennis. Pinning someone in the backhand corner with inside out forehands to induce the short ball you can then put away for a winner in the open court. Drawing someone into the net with a drop shot or slice so you can pass them. And beyond all of the strategy there is something meditative about sport – see the ball, hit the ball. Every part of it is addictive.

AO: I tend to think of sports as something that is used to define identity, whether as a player or a fan. But your relationship to tennis suggests the opposite: it’s a place where identity (or lack thereof) seemingly falls away as a result of the game at-hand. What do you think the popularity of sports tells us about American culture?

RL: There’s truth in both suggestions. The tennis crew I have, this community, we’re certainly defined through our love of the game and all of us have different stories on how we found the game. Most of my friends grew up with it, but there are a few of us who came to it later in life. All of us have different ethnic/racial backgrounds and the diversity is glorious. But always we’re bound together through the game. When I’m on the court playing doubles with a Nigerian as my partner, and across the net is an Italian and a Brit, and on the court next to us there are representatives from China and Argentina and India and Arizona, it feels like it should be a model for how the world can work.

Sports, like everything else, can bring out the best and worst of us as people. Examples of these poles can be seen daily.

AO: Do you feel that your insider-outsider status is part of what made you become a writer?

RL: I’ve never given this any thought, but it’s probably true. In fact, it probably is most definitely true.

AO: The book is made up of short essays with short paragraphs yet covers tremendous ground. Can you speak to the relationship between the cadence of the book and its subject?

Calls to ‘end racism,’ while well intentioned and a worthwhile goal, are futile. It’s like saying ‘end stupidity.’

RL: Like so many of us in this modern world, I see and experience everything in fragments. Originally, this book started as a series of braided essays, but then it morphed into a book length piece with fragments and diversions in any number of directions, but always tying into what the book is going after. I like your use of the word cadence because that’s always of paramount concern when assembling a book. Modulation makes the medicine go down, so to speak. Looking within and without, looking backwards and forwards, and all kinds of alternate side-angles, was critical in putting this book together.

AO: When/why did you decide this book needed to be nonfiction as opposed to exploring similar themes through a novel?

RL: I’ve never tried to do anything with a piece of fiction, have never sat down and decided on any kind of subject matter or theme, which is a term I never use. I never think in these terms when it comes to the work. All of it has happened through language alone, never an idea. So, there was never a choice. This book started as nonfiction and, of course, stayed that way. It would never occur to me to try it as a novel. I wouldn’t know where to begin.