interviews

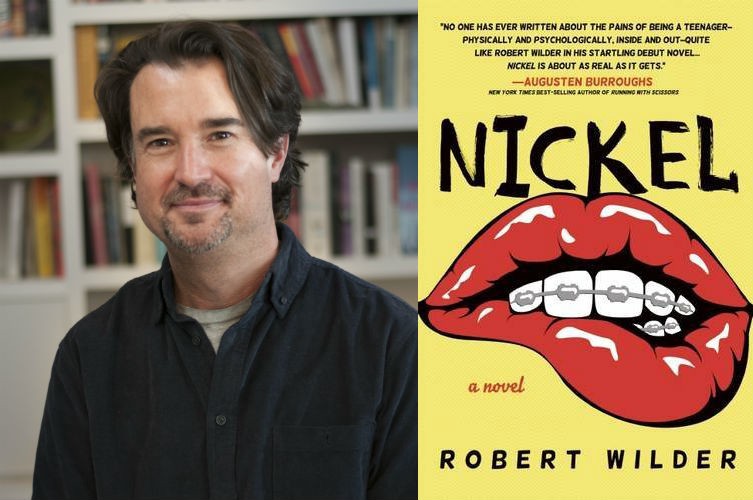

Robert Wilder’s Madcap Teenage World

The author of Nickel on the codes, traumas & mysteries of teens

In the new novel Nickel (Leafstorm Press 2016), we meet Coy and Monroe, two best friends with hundreds of pop culture references at their fingertips. Their lives are one long stream of jibs and jabs, a sort of zany Howard Hawks back-and-forth, madcap dialogue for the millennial. They sit comfortably on the fringes of their school’s social scene, comfortable in their comfort with one another. When Monroe starts getting sick, Coy’s world slips into harsh focus, raising questions about their friendship, and whether or not he can save it, let alone save his friend.

‘Nickel’ is not only a coin, it’s the source of Monroe’s allergy. But it’s the coin that kept popping into my head while reading — more money than a penny, but not enough to really get anywhere good. Larger than a dime, but worth much less. As big as the outsize emotions of high school, and just as undervalued.

I spoke with Robert Wilder over email about metal poisoning and teenagers.

Hilary Leichter: You did such convincing work creating the maximalist, pop-culture-soup of Coy’s inner monologue. He has a very specific way of articulating the world around him, and every sentence feels packed with allusions, puns, and slang. How did you go about building his vernacular?

Robert Wilder: All teenagers speak in some sort of code, not only to their friends but to themselves as well. This unique style of slang serves so many vital purposes and is constantly changing. I’ve studied my students’ slang for 25 years, not only in terms of their oral communication, but in their prose and poetry as well. Coy speaks code to his best friend Monroe because they are a unit and their unique shorthand unites and protects them. It’s really a form of intimacy. Coy also has an internal slang where he plays with language as a way to figure out a rather complicated life. My goal was to try to create a series of vernaculars for Coy to employ that shows how he navigates adolescence. I took pieces of slang from what I’ve collected over the years as a teacher and father and tailor-made it for who Coy is and who he wants to become.

HL: The book captures a lot of the cruelty of teenage-dom, the kind of merciless way that these characters see adults, see each other, and see themselves. Their gaze can be unforgiving. How did it feel to live in that space while writing the book?

RW: I have been doing a few school visits recently, and I tell students and faculty that being a teacher means experiencing a sad version of Groundhog Day, over and over. Every new academic year brings a whole new slew of teased kids or students sitting alone in the cafeteria or individuals feeling awkward class after class. Seeing this kind of pain always breaks a teacher’s heart and you can only do so much to prevent kids from suffering. Each new school year reminds me how both fragile and resilient teenagers are. I have deep empathy for all the characters in the book — teens, parents, teachers. All of us are so beautiful and so broken. I really carried all those emotions with me as I was writing Nickel.

HL: Are there any other young protagonists that informed the way you wrote the characters of Coy and Monroe?

RW: My own students and my son London and his friends were the best protagonists for me, but I also love Christopher John Francis Boone in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, Holden in Catcher (of course), and many teen characters in Lorrie Moore and Antonya Nelson’s fiction. One of the best books written about high school is Ms. Hempl Chronicles by Sarah Shun-lien Bynum. I was also influenced by my daughter’s music recommendations of bands like Girlpool and Slothrust. Phoebe Gloeckner’s graphic novel Diary of a Teenage Girl and David Small’s Stitches are both honest and moving and treat their younger selves with a keen eye.

10 Great Teens In Contemporary Fiction: A Reading List

HL: Can you talk about how your time as a teacher inspired or allowed for the research-project element of the plot?

RW: In terms of Nickel’s plot and shape, I tried to focus on the way a school year unfolds — how things are new and exciting in the fall but can quickly become mundane and tedious as the year goes on if we are not careful. I was also interested in how quickly things can change over even a brief winter or spring break. A lot can happen in those two weeks. I’m really a student on how schools react when kids get into trouble — whether it’s illness or behavioral or family trauma and how those issues can really change the course of a school year. There is constant cause and effect in any school; you just need to watch for it.

HL: There have been a lot of books written recently about kids who are sick, and the struggle is often a terminal illness. You seem to be twisting that narrative into something different — a diagnostic mystery narrative, where the mystery is the struggle. Was this something that you were consciously working towards?

RW: Absolutely. So much of our lives are a mystery, and I think we dwell far more in that uncertainty than in conclusions, oversimplifications, and melodrama. We know so little about so much. Most of us really have no idea how anyone else is doing. We often don’t even know how we are feeling in any given moment. I wanted the mystery of Monroe’s illness to mirror the mystery of Coy’s life. He has no idea when his mom will get “better” or how Dan really feels about having to raise a teenager or what his future will bring. We don’t learn and grow by the definite and easy-to-solve. We swim mostly in murky waters.

We don’t learn and grow by the definite and easy-to-solve. We swim mostly in murky waters.

HL: You’ve included a note in Nickel that the plot describes a “fictional medical situation.” Nickel allergies are a real thing, but what kind of research did you do to extend it as a metaphor and create a new illness?

RW: I did a lot of research on heavy metal poisoning and nickel allergies. It’s a fairly rare condition, and I put that disclaimer in the end so kids wouldn’t cut off their braces if they read the novel. I also wanted Monroe’s illness to strip bare everything around her, so there needed to be a few possible causes that her family and Coy investigate. I think that passionate dedication shows how much they all love Monroe and how often our lives or the lives of others can be boldly interrupted.