interviews

The Magic of Muslim Girlhood and the Quest for Liberation

Safia Elhillo imbues immortality to women rebelling under the patriarchy in her poetry collection, "Girls That Never Die"

Safia Elhillo’s much anticipated second poetry collection, Girls That Never Die, spins an incredible lyric around gender, body, desire, and control. The book yearns for a quest to be free, while living in a world where the body is policed by so many forces: womanhood, community gossip, changing countries, racism, islamophobia, language, self-censorship, secret love, fear, and living up to other people’s ideals and expectations. Elhillo’s poems push against what is, and move us towards what could be, what might be, and reach towards a freedom just beyond our grasp.

Elhillo’s work is undeniably and beautifully Muslim and femme—it puts us at the center of the table while protecting us with it’s softness. It’s the feeling I get from being in Muslim femme spaces; the safety to breathe, to relax, to talk loudly while eating pomegranate seeds, to be at home in our own gaze. The place where we get to say what ghosts our bones, what normally would be turned away from. And with this book, Elhillo shines her delicate light on what normally exists in the shadows—she calls it into the page even as she redacts it, as she shows us the space of our silences.

With this book we get to see a different side of Elhillo as well—at times sparse, at times filling the page with her words. The stories that we both can’t say and the ones that take up our whole being. A master in language, Elhillo conveys that through form as well as lyric, carving a new terrain, a sanctuary for the girls that never die.

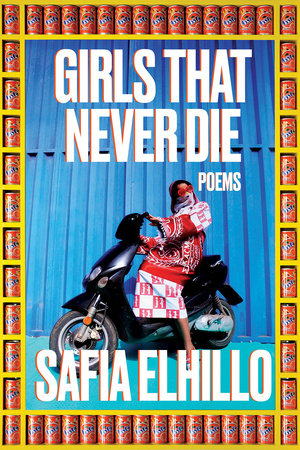

Fatimah Asghar: First of all, both the title and the cover art for this book are gorgeous. Can you give us a bit of insight behind how you landed both, and the significance of both the title and the cover?

Safia Elhillo: Thank you! I’d been holding on to this title for years, before there was ever a book—I’d spent years mishearing this Ol’ Dirty Bastard lyric from his guest verse on Ghetto Supastar: “I’m hanging out, partying with girls. That never die[s]” as “I’m hanging out, partying with girls that never die.” I knew I wanted to make something called “girls that never die.”

These are poems written from sites of pain and discomfort.

At first it was just one loose poem, but after the poem was done, I was still gripped by this fascination with that phrase, and knew I was nowhere near done with it. And a lot of my new poems at the time were thinking about shame and violence and my body, so eventually I started to think about what it would mean to repopulate those stories about danger, about the violences imagined and enacted against my body and my communities, with the girls from that misheard lyric: girls that never die.

The threat of death, the fear of death, is so often used as a way to govern and to control, so if the girls never die, won’t die, maybe they are free from that governance, from that control. And what could that look like?

In regards to the cover, I’ve been obsessed with Hassan Hajjaj’s work since I went to go see his ‘Kesh Angels exhibit in New York in I think 2014 when I was a grad student, and the images and the iconography were immediately so striking and so meaningful to me. I’ve had the same image from that series as my desktop background since then, for 8 years now. And when I was making the mood board for cover ideas, the mood board was like 90% Hassan Hajjaj images. Even the frames are so thoughtful—they’re hand-built and embedded with things like Arabic-language soda cans, Maggi bouillon packaging, things like that, which makes me spend time thinking about the Arabic language packaging that I grew up with for American products like Coca-Cola. And part of what compels me is the way the packaging makes a script as curvy and cursive as Arabic, graphic and bold and aggressive, which is the feeling I wanted to get from this cover, and the feeling I wanted to elicit with these poems. So to end up with an actual Hassan Hajjaj piece as the cover, when at first I thought the most I would get was like, a Hassan Hajjaj-inspired cover, is a dream beyond a dream.

FA: This is your second poetry collection, after The January Children. What were some of the things that you were navigating writing this second book after writing The January Children—thematically, emotionally, craft-wise?

SAH: The January Children was a project book—it was all poems organized under a particular conceit and a particular set of themes, which I already kind of knew about in advance, and so every time I sat down to work on that book, I knew where I was going to some extent. And it was a very, I don’t know, like a very tidy book. Very neat. Girls That Never Die was unruly. It was messy. One of the reasons it took so long is because I set about trying to write it the way I’d written The January Children. So, I tried to make it, you know, neat and tidy and organized, and have a conceit. That didn’t work. I tried to make it a book-length poem. That didn’t work. But before there ever was this book, there were a couple years after I finished writing The January Children, where I basically was trying to reteach myself to write poetry.

And I think one of the major formal differences between The January Children and Girls That Never Die is that Girls That Never Die has quite a few poems in inherited forms, in traditional forms—there are some ghazals in there, there are some contrapuntals in there, and it’s because one of the ways that I found my way back into writing poetry after finishing The January Children was through setting myself these kinds of low-stakes exercises in form.

The threat of death, the fear of death, is so often used as a way to govern and to control…

The January Children felt in some ways like a book I’d been writing, in one way or another, my entire life. And it was my first book, so before that I didn’t know what it was like to finish a project that I’d been working on for that long and to no longer have it organizing my life. So I felt really unmoored after I finished that book. Without that guiding conceit and without already knowing, almost every time I sat down to write poetry, what I was going to be writing poetry about, I just felt really unmoored. And so one of my main fears at the time was, am I still a poet, or was that just the one book I had in me? Was that the one set of poems I had in me? And now I need to go find something else to do?

One of the ways I found my way back to poetry was by setting these formal exercises, where I didn’t really have a relationship to a lot of inherited forms before that, and so I would sit down to try and write a sonnet for the first time. And when it inevitably failed, it wasn’t devastating, because I wasn’t trying to prove anything to myself about, like, my worth and value and ability as a poet in general. I was like, well, you know why this sonnet is bad? Not because I’m like a terrible, unworthy, finished poet, but because I’ve never written a sonnet before. So obviously it’s bad. So form was really helpful in transitioning between these books.

One of the reasons Girls That Never Die took so long to be finished, and why there are so many unusable drafts of the book, is because, again, I was used to writing a very particular kind of book. And The January Children is primarily a book about other people, in which I let myself be behind the lens. I was the eye, and that was maybe the most my body showed up in any of those poems, was through my looking, through my eye. But my body is not really in any of those poems. It’s not really under scrutiny in any way, or under observation in any way. It’s almost like my speaker in that book is basically a disembodied speaker, and at first I tried to write Girls That Never Die that way because it also is an easier way to write. To just look and not be looked at. And I’m not used to having to think about my body very much. It’s very often an afterthought, after like, my brain, and maybe my eye. Usually, the only times I would register myself as having a body is when something was wrong, in the way that pain often calls attention to the body, and discomfort often calls attention to the body. And these are poems written from sites of pain and discomfort. That was my body calling attention to itself, and for so many drafts of this book, I refuse to look at it because, you know, in looking at it in those poems, I felt like I would be inviting other people to look at it. And it’s scary. It feels like being naked in front of an audience or something, and so I kind of had to learn how to write a different sort of poem for this book. And it’s a type of poem that scares me and is very different from the kind of poetry I’m used to writing. Not that the poetry before that was like, so low stakes or whatever, but at the end of the day, I could write a poem pointing elsewhere and be like hey look over there, and in this book there’s no over there. It’s all like, look over here, and that’s scary and it’s new.

FA: So much of this book deals with body, femme bodies in particular—the body in the everyday, the body in community, and the body historically. I so deeply love the circular motion of the work, how it feels like there will be a poem that touches on a theme and then the next poem goes even further into that. In that way it feels like it resists surface level understanding, it resists the first or most immediate story and goes into layers and layers of the body. How did you approach writing such a difficult and vulnerable subject, and to do it with such deep precision and layering?

SEH: A lot of that layering and repetition and leaving and returning to subject is kind of indicative of a lot of my early fear and trepidation around the subject matter, where in the earlier versions of the poems would just barely manage to inch my way toward the thing I was scared to say, or think about, or look at. And right when I got to it, I would freak out and like, dismount and end the poem. And then I would get a little braver. And then there would be a next poem that kind of revisits the thing at a deeper level or a closer way of looking or in a way that doesn’t allow me to just exit the thought the second the thought is articulated, and so a lot of that motion is just me like inching close then freaking out, running away, coming back, getting even closer this time, freaking out, running away–and that cycle continued and continued and continued. It felt important to keep poems from all the different stages of that process, because I wanted to be honest about the process and accountable to the process. These poems are really just sites of trial and error. And I don’t know what these poems would even be like, or if they would even exist, without that sense of caution and fear and like, standing too close to the fire. I wanted a motion that showed that part of the process.

FA: A thing I’ve always found hard is writing about violence or issues within a marginalized (and heavily surveilled) community, because of the idea of not wanting to bring negative attention to the community. At the same time, we’re writers who are not spokespeople for any said community—we create stories and language that are specific to the lived experiences of our characters and speakers. How do you navigate that, in this book and in your other work?

SEH: You and I talk about this a lot, but it feels like there is this tension between wanting to speak truthfully about the things that I have experienced, without also perpetuating harmful ideas that the outside world has about my communities. So it feels sometimes like we’re not allowed to articulate any sort of critique or lamentation or grief in any public way, because then the racists and the white supremacists and the Islamophobes, or whatever, will latch onto it and be like Aha! You see! I knew it! When actually that’s not what was being said at all. But there is this fear of having my particular mourning and lamentation be twisted and used against my community in some way, when all of this is for my community. I’m not talking to other people. And so it’s tricky, because I always want to write as if only the people I’m talking to are listening, and everyone else can eavesdrop (on what hopefully is a very interesting, if maybe not entirely spelled-out conversation) but I’m also afraid of the things I am talking about being taken out of context and used to harm my community.

I think you and I have talked about struggling with this because sometimes it’s like, well, maybe it’s easier to just not say anything at all, but really that’s not an option. You stay silent for so long, but it builds up and it builds up and you realize that your silence doesn’t protect you or your communities either, and I think I had to just let myself speak and not silence myself with the fear of my work being engaged with in bad faith. If I was using that hypothetical as a reason to not speak, then I’m letting the, whatever, racist-white-supremacist-Islamophobes win. And I can’t have that either. I think I had to just give myself permission to do my thing and hope that it is found by those who need to find it and that it is not found by those who don’t need to find it. Because I can’t make my work from a place of fear. Because then I’m not going to make my work. I’m just going to keep quiet.