Novel Gazing

Salman Rushdie Helped Me Recognize Myself—and the Love of My Life

This may be the most romantic story about Salman Rushdie ever told

Novel Gazing is Electric Literature’s personal essay series about the way reading shapes our lives. This time, we asked: What’s a book that made you fall in love?

My phone buzzed at 5 a.m. I squinted at my screen, struggling to keep my heavy eyelids open. It was my fiancé, who was living in New York at the time. I was in Hong Kong. Our relationship was stretched taut around the globe and texts at odd hours were keeping it from unraveling. I sat up immediately.

“If you could have dinner with anyone, who would it be?” it read.

“President Obama,” I shot back.

“Not Salman Rushdie?”

“Oh duh — of course Rushdie, hands down,” I said.

“And if you could ask him anything, what would you ask him?”

The question left me confused because there is so much I want to say to him, so much I want to ask.

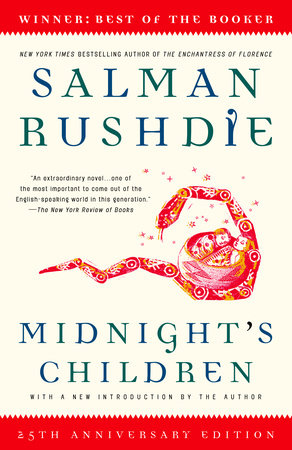

Where would I start? The moment I first picked up Midnight’s Children in high school? That was a part of my life that I now label as BR (Before Rushdie). Back then, I was a lanky nerd in Hong Kong trying very hard to run as far away from my Indian roots as possible. I would leave my mum’s hand-cooked lunch of potato-stuffed rotis uneaten and buried at the bottom of my backpack because of its embarrassing aromas of turmeric, coriander, and garam masala. I would strip, pluck, wax my arm hair and eyebrows, the thickness of which are so intrinsically tangled up with being Indian. I would lock away my love for Bollywood to make space for the Goo Goo Dolls, Oasis, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. And until then, I had never read anything by an Indian author; I just assumed they were inferior to the Chaucer, Charles Dickens, and Oscar Wilde classics we were studying at school.

I had never read anything by an Indian author; I just assumed they were inferior to the classics we were studying at school.

One day, I stumbled across a display at a bookstore that was dedicated to award-winning Asian writers. A friend of mine who had already read three of Rushdie’s books picked up Midnight’s Children and pushed it into my hands. “You need to read this,” he urged. I stroked its unbent spine, read the blurb, and decided to give it a shot.

A few chapters in, I was under Rushdie’s magical realism spell. I highlighted and annotated almost everything — every pun, every quip, every sharp observation of life, every riddle twisted into the plot. I bent its spine out of shape to a point where individual pages threatened to break out and flutter away.

Mrs. Braganza’s “gigantic pickle-vats and simmering chutneys” smelled like my mother’s kitchen at home. The twisty-turvy plot felt just as melodramatic as the Bollywood movies that I secretly, reluctantly loved. The ridiculous Sinai family were mirror reflections of my own family.

In the book, a pregnant Amina sits in the back seat of a taxi and descends into Old Delhi to meet Ramram, a fortune-teller who may be “a huckster, a two-chip palmist, a giver of cute forecasts to silly women” or “the genuine article, the holder of the keys.” My mother, perched on the back of a Vespa, headed to her trusted palm-reading friend as soon as I was born to see what the stars had in store for me. He told her two things of note: I will live far away and I will meet a man who will take me there.

When my parents moved to Hong Kong — barely a year after my prophecy — my father worked hard to give us a life he never had. An apartment in the bustling neon city, an international education, the luxury to follow my dreams. I, in return, wanted to live up to his expectations. He poured his soul into my future. I wanted to make it worth every penny.

When I picked up Midnight’s Children, I was nearing the end of high school, contemplating my future, tossing and turning just thinking about repaying my father’s sacrifices. Rushdie reached out through the book and into my heart to give words to the thoughts spinning around my conscience: “I must work fast, faster than Scheherazade, if I am to end up meaning — yes, meaning — something. I admit it: above all things, I fear absurdity.”

How did Rushdie know exactly what I was going through? How did he understand me so well? I wasn’t the only person who connected so intimately with Midnight’s Children. Reviews of the book when it first came out famously described it as “a continent finding its voice” because it was so richly Indian, so truly relatable for the country. How did he understand us so well? Is that the question I wanted to ask him?

Perhaps I should tell Rushdie about my journey after Midnight’s Children (also known as AR, After Rushdie). The book cracked open a door ever so slightly and I pushed through with gusto, finding more pieces of myself in his other books as though Rushdie was now my fortune teller giving me, the bewildered hopeful, answers.

I leaped from Midnight’s Children to Shalimar the Clown. There I saw elements of myself in India Ophuls because I had reached an age where I yearned — like she does — to learn about my roots. Instead of shoving questions about my family’s history and my country’s past aside, I now wanted to confront them. That book painted the picture of the raw hatred that to this day tears India apart in a way that even my family who grew up there couldn’t put into words.

The book cracked open a door ever so slightly and I pushed through with gusto, finding more pieces of myself in his other books.

Then, at the start of university in London, I started to sink my teeth into The Satanic Verses. As I struggled to turn this rainy, moody city into my home, the protagonist Salahuddin Chamchawala was trying to do the same. My education there turned into a financial burden for my father. So my three years were glorious and unforgettable but also weighed down by “a nightmare of cash-tills and calculations.” Salahuddin’s realization that “England was a peculiar-tasting smoked fish full of spikes and bones, and nobody would ever tell him how to eat it,” was one that resonated with me too. At some point, like Salahuddin, I figured out how to eat the fish.

Again and again, at every juncture of my life, Rushdie was reading me while I was reading him.

By the time I landed on Joseph Anton, Rushdie’s memoir of his time in hiding, I was two years into my journalism career. My family wasn’t convinced this would be a long-term and fruitful path. The professional moves I wanted to make next were met with doors slammed in my face. Almost every route I took led to a dead end. I felt boxed in and worried that I would end up being just another absurdity, a blip, a speck, a disappointment. And right when I thought I had hit rock bottom, my previous boyfriend broke my heart. That one-two punch snuffed out the lights.

My cracked being turned to Rushdie for consolation. In Joseph Anton, I learned that India — his country, my country, our country — was the first to leave him twisting in the wind for writing The Satanic Verses, a fact that is so frequently overshadowed. India’s narrow-minded knee-jerk ban on the book placed the country on a slippery censorship slope that it is still riding today. I got a detailed look at his personal life under the Iranian Fatwa, which was so quickly destroyed as though he was a meaningless paper figurine that can be scrunched up and tossed aside. The entire world told him to put down his pen for the greater good. Yet he persisted. The path of self-doubt and dejection I was on was nothing compared to his. His strength through it all, which roared loud and clear in Joseph Anton, encouraged me to keep going. But I never figured out how and why he managed to find that determination and push through, despite such high stakes, while I in my own small world was willing to give up so easily. That — that’s what I would ask him.

“Why he kept going when the whole world told him to stop,” I texted my fiancé.

My fiancé. I was still getting used to saying that. I first met him exactly a month after I got through Joseph Anton. It was Halloween. He was dressed as a mad scientist, with fake blood splattered all over his lab coat. I was dressed as a sheriff, star badge and all. I was floored in five minutes. He was nonchalant and uninterested in me. He didn’t even ask for my number. So I gave him my sheriff badge, hoping that in the sobering morning light it would make him think of me.

At every juncture of my life, Rushdie was reading me while I was reading him.

It didn’t.

I found him on Facebook and realised the origins of his resistance were tied to an exam he was studying for.

Three weeks later, after back and forth messages, after his exam, we went on our first date. He charmed me with his humour, his puns, his quips, his sharp observations of life. We went for an Escape The Room game with nothing but riddles to find a way out. It all sounded like a Rushdie novel. And I was falling in love.

Three years later, his company flung him across the world. But he didn’t leave me behind. He rented out a room at the glitzy Ritz Carlton and turned it into our very own Escape The Room. A box with a clue led to another then another then I found that same sheriff badge and, taped to the back, a diamond ring. I couldn’t contain myself.

So here we are now. Me in Hong Kong, my life packed up in boxes ready to move far away. Him in New York, texting me about hypothetical dinner dates.

Three months later, it’s our wedding day at a small Hindu temple. We’re walking around the ceremonial fire. We’re exchanging garlands. We’re bowing our heads in prayer. Now, we’re united and sitting in chairs to take pictures.

My husband hands me a neatly wrapped present. “Remember what you told me you’d ask Salman Rushdie?” he said. I ripped through the wrapping and found Rushdie’s latest book, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights. Inside, on the first page, a response:

“Alisha,

Free speech matters more.

Salman Rushdie”

Tears blur my vision and my jaw drops. “But how…?” I ask my husband. That moment confirms what I already know — I am going to love this man forever.

“I know people,” he says, shrugging and smiling.

I wonder, now, what would have happened if Rushdie didn’t care enough about free speech. I might not have read him at every one of my crossroads. And then what?

I may have never made space for an understanding of who I am and my country. I could’ve ended up hating London rather than embracing it. I may have locked my broken heart up in my chest, closing it off from the man who would bubble wrap it and take me far away.

In Midnight’s Children, Rushdie poses the question “where, then, is optimism? In fate or in chaos?” For me, it seems like fate.