interviews

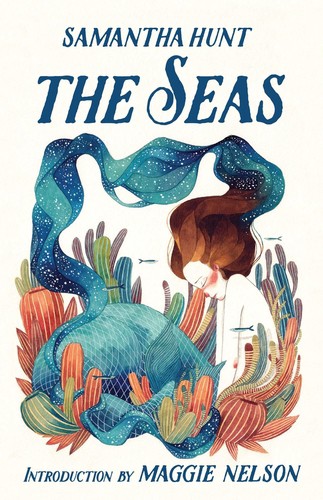

Samantha Hunt Transforms the Mermaid Myth into a Feminist Allegory

The author of ‘The Seas’ on creating a new reality through language

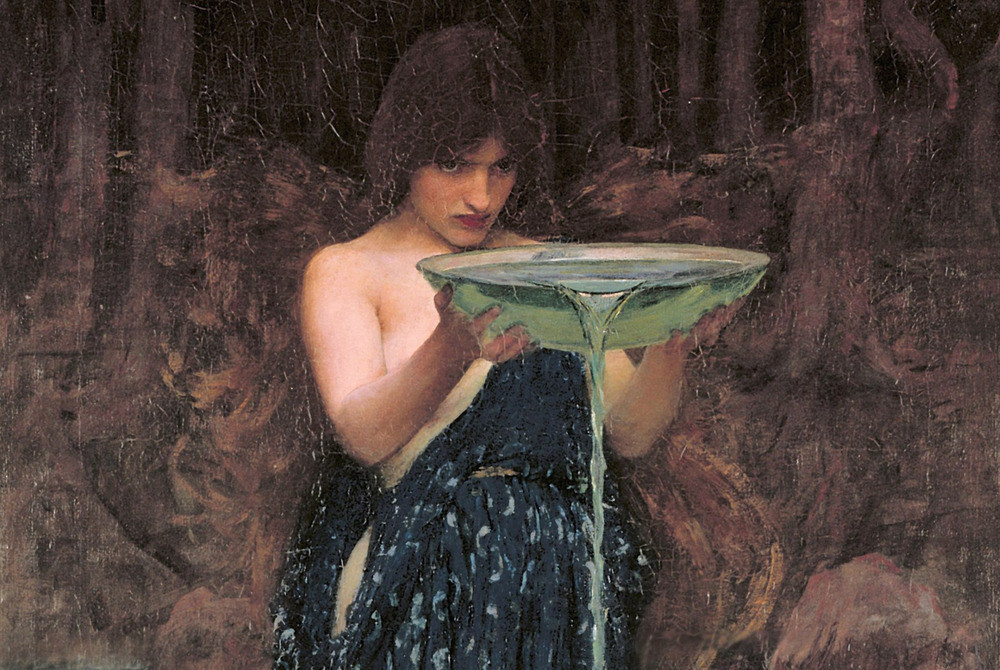

The Seas, Samantha Hunt’s first novel, is as disturbing as it is beautiful. It is a literary equivalent of the Rubin vase, the ambiguous image, multistable perception that shocks us back and forth between two possible realities of a story all dependent upon the gaze of the reader at particular moments. Our narrator is either a real mermaid or a schizo-affective depressive circling down the drain of a heavy mental breakdown. We think we have to choose between these sides of perception but we don’t. The richest understanding of The Seas comes as we see that these two interpretations are not mutually exclusive. We can witness the vase and the face.

To see The Seas alone as a love story between mermaid and man would leave it without the depth of its tragedy and humanity. It is not only a mermaid story. It is the story of a young woman struggling for meaning in her lonely world, striving for love and connection at any cost; and if such meaning cannot be found in her material world then she will construct it herself. The story is a lenticular print — nothing flat and matter of fact — a photo shifting as the light hits it from different angles. There is the illumination of the story through fantasy, and there is its illumination from psychology; both scales, sides of history, enriching alone, but most valuable to our language as the interpretations come together.

Samantha Hunt comes from a scientific background, a geology student turned creative writer, she has a trust in the creative power of science. The potential of language within the realm of the scientific pushed her ever deeper into the crafting of words, a craft we can see clearly forming in The Seas. The Seas was reissued this year by Tin House with a provocative introduction from Maggie Nelson.

I spoke to her about psychology and mythmaking, structuralisms and relativisms, and the need to bridge the gap between the two.

Marlena Gates: There exists in the narrator of The Seas a longing for convergence of science and myth in the making of her identity. How do you see the stark division of the arts and sciences, storytelling and experimentation, in our current culture? Does it hinder us as humans more than help, especially in dealings of the language of psychology and mental illness?

Samantha Hunt: Something surely is broken, something that could anchor humanity in compassion rather than greed. Imagined binaries are part of that. However, we are also living in an era where science is seriously threatened by capitalism, climate change deniers and an opioid epidemic courtesy of the pharmaceutical industry in the name of medicine. But, as your question asks, in the making of identity, story and science are brain and skeleton, respectively. I like to imagine that anatomy model, the myth organ tucked in by the pancreas. There are a number of artists making wonderful scientific experiments. What freedom.

The world dismisses girls, stories and the imagination. I do not. I have three daughters, three sisters, three nieces, even three moms. I am surrounded by girls who tell me stories I believe. One daughter asks, “What does the sun smell like?” What an important question, an investigation that is narrative and science. This is what I can do to change the parts of the world that hurt me. We understand the natural world best through narrative, just as we understand justice, death, the ocean, illness, and love, through narrative.

The world dismisses girls, stories and the imagination. I do not.

MG: I believe a book as The Seas can help us to understand disassociation and identity disorders better than most psychology textbooks, as it shows us the personal and structural reasons why people need myth-making to survive. What can you say about this? If allowed, can magical realism perhaps inform our understanding of mental illness — particularly schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorders?

SH: I wonder if need is a strong enough word for our relationship to myth or story or imagination. Whatever we call it, it is creation. Try to think without language. It is impossible for someone who has learned to speak. I look out my window now and there is the story of blue, the story of green. Are our stories of green the same? Not exactly but close enough I hope that we can use words to understand one another in a word-less moment of greenness. Here’s the fascination with Kaspar Hauser and others who did not learn language until later in life. What was thought to Kaspar? Image alone. I don’t know much about schizophrenia but I do know that storytelling is human, helpful, eternal, compassionate and unlimiting whereas diagnosis sets a boundary that constricts. Boundaries are sometime helpful. It’s true. For example, the boundary of a period, imparts the sense to the end of my sentence. But boundaries are really only helpful when the body in question is the force setting that boundary.

MG: Could magical realism be understood as modern-day mythmaking?

SH: I don’t often use the word magic. Magic is easily gendered and dismissed. I do not separate stories from my material reality because when I ask, “What am I made of?” the answer is: William Faulkner, Toni Morrison, Madeline L’Engle, micro histories my parents told me of their lives. I’m made of the books I read as a girl, a lot of them fictions. (A more honest accounting would also include V.C. Andrews and Danielle Steele, plus every Choose-Your-Own-Adventure I could order from Scholastic.) I also don’t separate myth from history. I lived in Ireland when I was a teenager. Someone took me to Queen Medb’s tomb, a tremendous mountain-size limestone cairn. I said, “I don’t understand. Queen Medb isn’t a real person, right? She’s a story. Why does she have a grave?” They’d look at me with pity, thinking it so sad I still believed there was a division between history and myth. I still thought George Washington cut down his father’s cherry tree.

The danger in thinking this way without reality boundaries (that period) is that one could argue this is how we’ve arrived at fake news. This has been troubling me lately until a wise man recently reminded me that there is a big difference between truth and fact. Stories are true. Untrue facts are lies. Alex Jones is not a fiction writer. He’s a liar.

The other side of this answer is that when I read Octavia Butler or George Orwell here and now, I see how science fiction work from twenty, thirty, a hundred years ago was an amazing act of reading signs, following logic to see where we were heading. Writers of science fictions are Cassandras sending out early warnings.

MG: In a way, the narrator was quite accurate in believing she had an eye problem. Research shows that how the eyes move and focus correlates directly with schizophrenia and depression; patterns are clearly there yet doctors are at a loss to understand them; whereas, our narrator seemed to understand her case better than them in that way — she really did have an eye problem. Did you know about this clinical research or did you write the narrator’s obsession with her eyesight organically?

SH: Again, I don’t know much about schizophrenia but what fascinating research. I use my narrator’s eye problem to address the idea of forming identity in a small town. What do you see? What do you not see? How does what others see about me, shape my person? We put such firm trust in our vision when we already know that our eyes are actually spotty and poor perceivers, giving speckled information to our magnificent brains that do the work of filling in all of vision’s holes, in order to present a wholeness. Vision is already imagination yet we trust it implicitly. Why then are we so suspicious when it comes to imagination and metaphor?

The Seas is all about taking words that wound you, and changing the meaning of those words. Call a young girl crazy. Call her a slut. If she is creative, if she is free, she will learn to make something new from that old cloth.

MG: Disassociation and delusion or displacement and identity crisis; how much does the distinction between our narrator’s created mythos, and her diagnosed delusion (from mother and doctors), matter?

SH: So, you don’t believe she’s a mermaid? I sometimes think of The Seas as a measure of optimism. Whether or not she is factually a mermaid matters less to me than her truthful reasons for needing to be one. I won’t separate her from her imagination. A number of people in my life see ghosts. I don’t particularly believe in ghosts. But, I believe the people who say they believe in ghosts.

MG: Our narrator is convinced she is a mermaid even as everything warns her of the danger to the man she loves, Jude, if she really is. In my reading of The Seas, I could not help return to the feeling that this story has so many larger implications for the strife of modern-day relationships — with men and women so painfully alienated from one another. If the mermaid is a creature born from a mythic “war of the sexes,” how much is The Seas, in a sense, about the impossibility of love in a time of gender warfare?

SH: The myth of the mermaid is such an odd horror. We created females who are really sexy, have no genitals, are freezing cold and kill men. That’s nuts. And then we sell this image in every seaside gift shop as an attempt to modify the myth. We make it desirable. We make it about swimming. There’s a lot of unpacking to do around the mermaid. Sex and fear, desire and the ocean. I couldn’t resist trying to understand this complicated thing through a wounded adolescent girl, brimming with passion and lust. Jude is very messed up. It’s true. He’s got PTSD. He’s an alcoholic. He’s probably dead. But he does manage to take care of the narrator. How we care for other humans is of great interest to me. So, I give her the position of power, the murderess mermaid, and hope that compassion wins out.

MG: How much is love always about seeing the other through the Mercator projection?

SH: Isn’t there something wonderful about that though? Isn’t that proof that we tell stories not to avoid an idea of truth but because we are creative, adaptive, hopeful and generous creatures. I love Mercator’s Projection. I remember the example my teacher used was tiny Iceland. On the flat map, it gets to be a giant. That resonates with me. Iceland dreaming of hugeness. One of my daughters is very small in body and yet, anyone who knows her would absolutely call her a giant. Mercator’s Projection gets to the heart of how narrative twists a body, for good or bad and love, as mode of exploring the other, will of course have to grapple with questions of perception.

MG: Untranslatable words, arcane words, lost roots, all the characters seem lost to find the right words for their experience of loss and trauma. They have lost the “L” to their “ost oves” — yet, still, language hovers over them all. How much of The Seas is about the need to find a language for loss, for identity, for love in a time of impossible strife?

SH: The Seas is all about taking words that wound you, and changing the meaning of those words. Call a young girl crazy. Call her a slut. If she is creative, if she is free, she will learn to make something new from that old cloth. Call a father dead, and then see how perhaps he’s simply swimming in an ocean large as all time.

Also, I love old dictionaries. I love learning the stories behind etymologies, say how the woman Dangerose becomes dangerous. I love writing fake etymologies too. Naming is narrative. My grandma was a poet and was once asked to name a new road. She called it Lilac Lane. Simple, sturdy but saccharine. I thought about that for a long time, how the name would affect the people growing up on that road.

I sometimes think of The Seas as a measure of optimism. Whether or not she is factually a mermaid matters less than her truthful reasons for needing to be one.

MG: Our narrator craved meanings, even if not her own, even if made up. Was it an intentional irony that your narrator craved affectation in a sense — in her fascination with science and obscure words — yet these words were ever absent?

SH: I studied geology in college. One of my favorite texts books was Waves and Beaches by Willard Bascom. In that book, Bascom writes that there are hundreds of waves that have yet to be named. This idea has stayed with me for two reasons. The first reason is because it makes me wonder about human’s adorable ideas of ourselves. The ocean doesn’t care what we call it. But, reason two, is that language matters deeply to me. If I named one of those waves “bunny rabbit” that would surely change how we think and feel about it. Language, despite its shifting nature, is extremely real, extremely affecting. And science does not leave me cold. Science loves me back. It took me a long time as a young woman to know that I was half of every couple I made. I do think that identity troubles are often a problem of lost or missing language and if someone can provide the right word to you, what a gift, a new window.

MG: Was the narrator’s determination to create meaning out of what was available to her, through storytelling and magical interpretations, a way to distance herself from the stark truths of her dark and damp post-industrial waste of a town? And do the sad reasons she created her stories matter, or is it what is created that matters, or both?

SH: Telling stories is an act of hope. She doesn’t like the reality she’s been dealt and so she will fashion herself a new one through language. That doesn’t feel sad to me. Words make matter, material. She’s making a new world that doesn’t hurt so much.