interviews

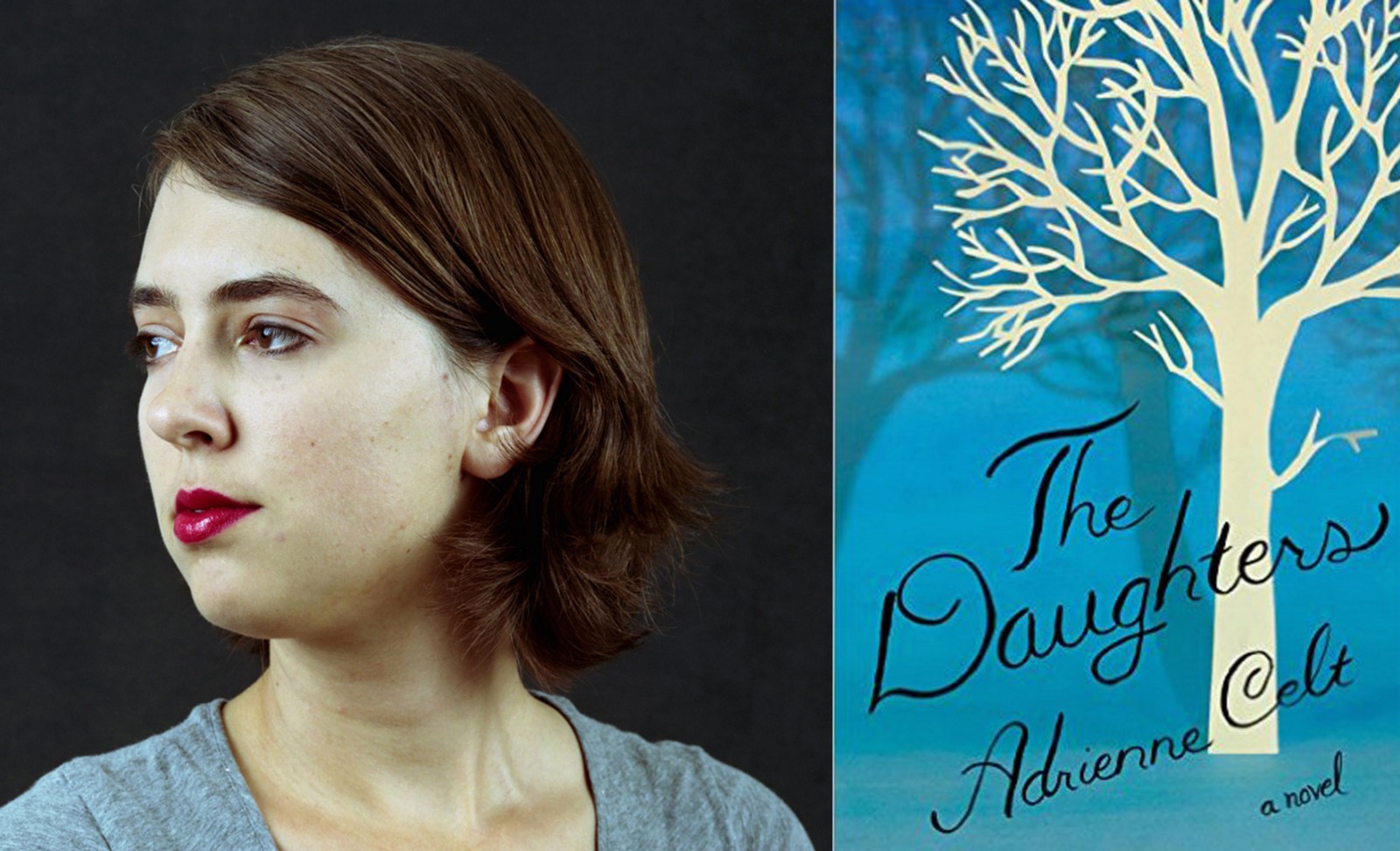

“Scary Baby” Stories: An Interview with Adrienne Celt

Adrienne Celt’s upcoming novel The Daughters is excerpted in the most recent issue of Recommended Reading. In the interview below, Adrienne answers some questions regarding her writing process and her inspirations.

Katie Barasch: You capture the nuances of mother/daughter relationships so well in this excerpt from your novel The Daughters. Have you found this to be a recurring theme in your work? Do you find that the mother/daughter relationship is one of particular complexity?

Adrienne Celt: An interest in parenthood and children is definitely a recurring theme in my work — a good friend/treasured reader of mine calls these my “scary baby” stories, probably because I find there to be something uncanny about children, which I keep coming back to. (And I don’t mean that as a dig at children — really, I’m jealous of them.) I guess I would clarify, though, that what captures me most is the relationship between child and adult minds: how the fact that a single person can exist in these two very different states expresses something about the simultaneous permanence and transience of our identities. Children are so boundless in their energy and instincts: they haven’t hardened into any one narrative about their life the way that adults tend to. I look back very protectively on my childhood self, almost as though she was another person entirely.

That said, I do think there’s something particularly complex about the relationship between a mother and child, because the new mother is not only being forced to rethink her own identity, she’s also an intimate observer of the drama of the child’s developing mind. Here is this brand new person, unfolding as a unique being and interacting with the world for the very first time, and on the one hand the mother has critical distance because she’s an adult and she knows what’s going on. (By which I mean: discovering cause and effect by dropping a spoon over and over is not as mind-altering for the parent as the baby.) But in another way, every change is as deeply personal for the mother as the child — both because the baby is flesh-of-her-flesh, and because she understands more deeply than ever before that this is something she went through, too — that it’s what all human beings go through in the process of becoming.

Barasch: In The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir writes, “For the mother, the daughter is both her double and an other, the mother cherishes her and at the same time is hostile to her; she imposes her own destiny on her child: it is a way to proudly claim her own femininity and also to take revenge on it.” Do you see validity in this statement, and does it pertain to Lulu and her mother, Sara?

Celt: I feel like I should say, at this point, that I am not a mother. Maybe I will be, but my experience and fascination with children comes primarily from having known, for my whole life, that I had this possibility within my body, and that there was an expectation that I would fulfill it — which then kind of obsessed me. Did I want to have a child? What would it mean about me, and my dreams, and my personality, if I gave myself over to another person in that way? (All still open questions, obviously!)

All that is to say: I don’t claim to speak for women who are mothers, and can only bring to this conversation my experience as a daughter, as an aunt, and as a writer who has thought a lot about these issues on her characters’ behalf. But to answer your question: I guess I don’t know anymore. I think there was a time when I would’ve unquestioningly said that yes, the cherishing/hostile, loving/imposing dichotomy is correct, but now I’m not so sure — maybe because I read that statement as slightly hostile in and of itself. I do see some validity in the idea of a daughter as a double/other, because the child’s life, her body, literally comes from the mother’s life and body — and yet she is her own being. Certainly for Lulu and Sara, that is a tension. But overall, I prefer Maggie Nelson’s discussion in The Argonauts about pregnancy and motherhood as both radically queer and radically conformist, because I think that it points any hostility in the right direction: towards the strictures of social norms, and away from the individual intimate bonds between parent and child, self and other, body and identity.

Barasch: I was struck by this line: “Here is the thing you must understand: to know an opera you must be part of it. You must emerge into its world and lose yourself there with no hope of ever escaping completely. No matter where you go, the pitches and tones will follow you. The arias will pop up at inconvenient moments, and you’ll see the characters ducking into alleys years after you last met them onstage.” For me, this description evokes the immersive experience of reading a great novel. Were you thinking about that when you wrote these lines?

Celt: Art is immersive in all its forms, though every form has a different flavor, and one of the pleasures of writing about opera, for me, is that the performance is so physical — whereas reading and writing are mostly cerebral. You can be immersed in a book, but that experience comes from the intellect and the imagination, whereas music is actually engaging the body. I do think there are similarities, certainly, but it’s the differences that really intrigue me.

Barasch: Music plays an important role in this excerpt. As an author and as a human, how would you describe your relationship with music, including opera? Do you listen to music while you write?

Celt: I took voice lessons as part of my research for The Daughters, and as a writer it was important for me to get in touch with the physical discipline required of singer. I’ve always loved music — I played the flute semi-seriously in high school, I was a devotee of the mix tape until CDs and then MP3s took over — but my appreciation has mostly been that of a fan, not an artist, and it wanted for a bit of structure. I became interested in opera when I was living in Russia, where it’s often cheaper to see live music than to go to a movie. One night I went to see Verdi’s Macbeth, and they had a leaderboard with Russian subtitles to help you follow the Italian text, but I forgot my glasses, so it was all just a bright smear above the performers. And the great thing was — it didn’t matter. The music was so much more important than the words. That’s a transformative experience, for a writer, when the words suddenly don’t matter.

Normally I don’t listen to much music when I write, because it can be distracting (luckily, that’s not a problem with comics), but there are always a few pieces that get me in the right headspace, and which I play over and over again — lately it’s been Arvo Pärt’s “My Heart’s In the Highlands.” I tend to stumble on these pieces accidentally, so like all inspiration, the music that moves me has some relationship to kismet.