Recommended Reading

“Scenes of Passion and Despair” by Joyce Carol Oates

Maryse Meijer recommends a previously out-of-print story about how toxic notions of romance destroy us

INTRODUCTION BY MARYSE MEIJER

“Scenes of Passion and Despair,” from Joyce Carol Oates’ monumental story collection Marriages & Infidelities, begins in mud and ends in bone. Over the course of fourteen “scenes” a woman, running along the Hudson towards her lover’s cabin, ruminates in a series of fourteen short meditations on the nature of her relationship to the men in her life, and of herself to her body. What is remarkable to me about this piece — and so much of Oates’ work — is its revelation of the ways in which toxic notions of romance drive and destroy relationships.

This is a story designed to interrupt our assumptions about all kinds of sex, refusing titillation in favor of horror and revulsion in moments both transcendent and mundane. Nothing seems to truly please the protagonist; she is more often repulsed by her lover than drawn to him, and every physical act between them is saturated in violence, and yet she offers her body again and again, sacrificially, in order to prove to herself — and to the Other, and to the reader — that the violence is necessary, inevitable, and, ultimately, desired.

This is a story designed to interrupt our assumptions about all kinds of sex, refusing titillation in favor of horror and revulsion in moments both transcendent and mundane. Nothing seems to truly please the protagonist; she is more often repulsed by her lover than drawn to him, and every physical act between them is saturated in violence, and yet she offers her body again and again, sacrificially, in order to prove to herself — and to the Other, and to the reader — that the violence is necessary, inevitable, and, ultimately, desired.

Throughout the piece there is a profound disconnect between what the protagonist feels, and what she shows. There is no hint that either her husband or her lover guesses how often her supposed love for them twists towards hatred; the lover never seems to notice or share her impression that their lovemaking is ugly or grotesque or painful. The men in “Scenes” are mere still points waiting at either end of a path she seems hysterically compelled to tread, increasingly alienated from pleasure. Trash is everywhere; the Hudson is polluted, the riverbanks are choked by weeds and debris, the woman is mired in mud as she hurries towards her lover, even as in her mind she is often thinking of escape. These relationships, like the Hudson, are polluted; the human bodies are as defiled as the body of nature, cruelly, carelessly used as a means to some unworthy end.

Oates’ characters often seem to want to make love, are in love, perceive themselves as driven and consumed by love, but they are, in the end, often only fucking, or being fucked; they are being destroyed. What other option, Oates’ stories ask, is there? If sex is supposed to be about communion, but we as a society despise community, what does making love look like? Oates’ protagonist never gets out of her head, and neither do we; it is a profoundly suffocating story, where passion is despair, where consensual sex is sometimes indistinguishable from rape; where desire sickens and humiliates the flesh. Here the body can never truly meet another, because it cannot tell the truth of its experience of violence: when the lover asks if he is hurting her, the protagonist can only lie, to him and to herself; that there is no pain, or that the pain is of no consequence, even as her flesh is — in an incredible enmeshment of the literal and metaphorical — stripped from her bones.

I’m a writer after Oates’ heart; I’m fascinated by desire, by what it does to us, what it moves us to do to one another. I love to uncover the extremes hidden within our most common experiences. And, too, I’m obsessed with the experience — of both men and women — of sex, which appears to so many of us as yet another apparition of loneliness, instead of the communion we might wish it to be. This story, written almost fifty years ago, is as intensely relevant to my own experience of sexuality and desire — and, I would argue, to our current sexual-political moment — as anything being written now. We are still living, and loving, under a liberal capitalist patriarchy, which is a bit of a horror story for us all. How to survive the summer? the protagonist wonders. But there is no summer in this story; there is only one twisted telescope of time, encompassing an entire life that refuses to stick to a moment, because every moment collapses into other moments, every act of violence pointing to others violences, pushing the protagonist’s body out of the linear and into the perpetual; there is no escape, for her or for us. The story devolves into pornography, death, debasement — but it doesn’t end; it hurts, silently, invisibly. Again and again, the woman thinks, of both of the men in her life: I don’t know you at all. In a delusional Oatsian landscape, as in our own, knowledge of the Other is often impossible; and in the absence of knowing, there is always, everywhere, violence.

Maryse Meijer

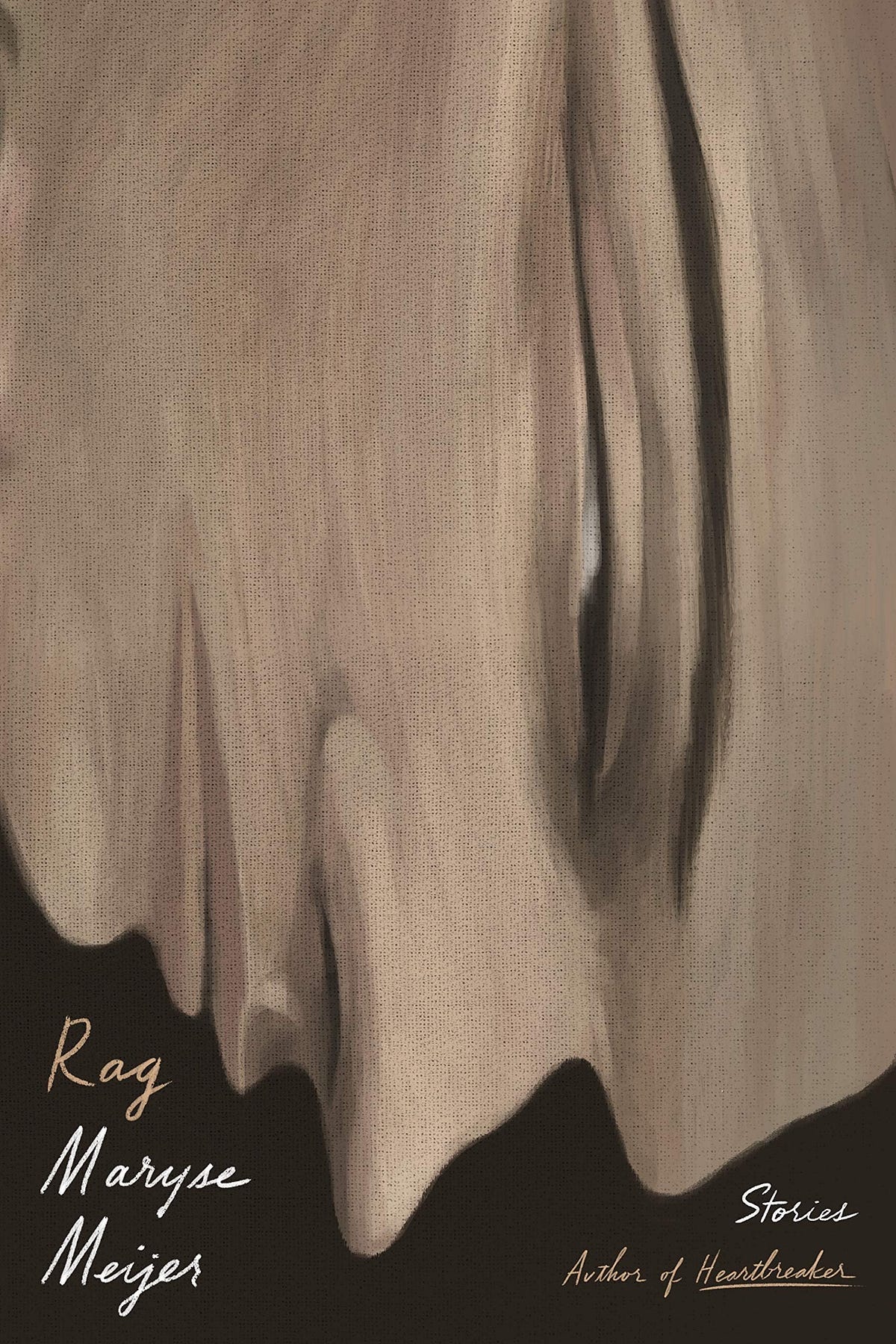

Author of Rag

“Scenes of Passion and Despair” by Joyce Carol Oates

Joyce Carol Oates

Share article

“Scenes of Passion and Despair”

by Joyce Carol Oates

1

Walking quickly. The path become mud. She walked in the weeds at the edge of the path — then, her good luck, some planks had been put down in the mud, for cattle to walk on. She walked on the planks.

A hill leading down to the river, bumpy and desolate. Ragged weeds, bushes, piles of debris. No DUMPING ALLOWED. The Hudson River: she stared at the wild gray water and its shapelessness. Familiar sight. She’d been seeing it from this path, hurrying along this path, for weeks. Weeks? It was only the end of June and it seemed to her the summer had lasted years already. How to survive the summer?

The planks wobbled in the mud. Her legs straining to go faster, faster. Down on the river bank were old bedsprings and mattresses, broken chairs, washing machines. . . If one of these planks slipped she might tumble down there herself.

Her hands up to her face, warding off the stinging branches. Almost running. Sometimes she slipped off the cow plank and into the mud, her shoes splattered, damp; she felt with disgust her wet toes inside the gauze of her stockings. Heart thudding impatiently. The eerie light of this June morning, still half an hour before dawn: would it turn into an ordinary day later on? Could this gray still air turn into ordinary air, riddled with sunlight and the songs of June birds? Up at so early an hour, alone on the river bank, alone hurrying along the path, she felt her cunning and yet could not keep down a rising sense of panic — was this visit going to be a mistake? Did he want her? Why this particular June morning, before dawn? Why this particular dress of hers, a blue and white flowered dress, cotton, with a dipping white collar with machine-made lace, why this, why its looseness as if she’d lost weight, why the light splattering of mud and dew across her thighs? And why did she take the cowpath, why not dare the road?

Now she cut up from the path, up through a meager clump of trees. Legs aching from the climb. The house came into view suddenly: an old farmhouse, fixed up a little, the chimney restored. A car in the driveway, mud puddles stretching out long, narrow, glimmering around it, the water crystalline at this hour and at this distance, as if it meant something. Rehearsing her words: I had to come — I had to see you — Panting. Brushing strands of hair out of her face. Tried to imagine the exact appearance of her face — her face was very important — her face — her face and his face, confronting each other again —

She ran to the front door, up on the rickety porch. Uncut grass. A real farmhouse in the country. Near the Hudson. She did not knock, but opened the door, which was unlocked — You don’t even have to lock your doors — went inside. Heart pounding desperately. She called his name, ran to his bedroom at the back of the house — in the air the smell of his tobacco, the smell of food from last night — the slight staleness of a body in these close, cluttered rooms — he was waking up, his hair matted from sleep — staring at her in amazement —

She ran to him. I had to see you — He interrupted her, they embraced, a feverish embrace. The blank startled love in his face: she saw it and could not speak. Had to see you —

Wonder. His voice, his surprise. Hips jammed together, bodies cool and yet slippery as if with the predawn dew, the start of the birds singing outside, ordinary singing for June, the rocky tumult of the run along the path, the planks, the mud puddles, the banks of the river, her mind flitting back to the house she had run from, running out in her blue and white cotton dress, no scarf on her head, shivering, reckless, calculating the amount of time she had before her husband — who had left for the airport at 5:30 — might get to New York, might telephone her to check on her loneliness —

So long, you bastard.

2

Hips jammed together in languid violence. A need. A demand. Do the leaves glisten outside in the lead-gray air? Are they strong enough to last all summer? Only June, the flesh of her face is not firm enough to last. Her lover’s hands, chest, stomach, his face, his soft kindly mouth, sucking at her mouth, the force of him jerking the bed out inches from the wall, the heaving of covers — she sees how grimy the khaki-colored blanket has become — her lover’s parts are firm enough to last all summer, to last forever, even if she wears out.

How many times had they loved like this, exactly?

Lost count.

He is saying something: “. . . is he like now?”

“What is he like? . . .”

“With this, with us . . . doesn’t he know, doesn’t he sense it . . . what is he like now with you? Can’t he guess?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think about it.”

“Does he drink a lot?”

“No more than before.”

“Can he sleep?”

“No more than before. He’s always had insomnia. . . .

“Do you sleep beside him, then, can you fall asleep while he’s awake? .. .”

Wants to know if that other man, my husband, still makes love to me.

“I don’t know. I don’t know him at all.”

3

The cow planks sigh in the oozing mud, she runs holding her side, panting, her bowels feel like rocks this morning, poison, poisoned; she hates the man she is running from — eleven years invested in him — and she hates the man she is running toward, asleep in that room with the bedraggled wallpaper, and no telephone in his authentic rented farmhouse on the Hudson River, so he brags to his friends; she must run to him shivering, her face splotched from the slaps of branches, saliva gathering sourly in her mouth as if forcing her to spit — Can’t stop running. Her heart pounds. Can’t look down at the river because it is so brutal, a mass that would not support her weight if she suddenly slipped down the bank; imagine the shrieking, the lonely complexities of thought, the electric shocks of terror as she drowns, having a lot of time to reconsider her life — And then they would fish her body out of the river a hundred miles downstream. So long, my love.

The cow planks sigh and bounce. She runs up the hill to the farm he has rented, her flesh aches to be embraced, she scrambles up the hill in her muddy ruined shoes, panting, and she dreams suddenly of an ice pick — wide-awake, she dreams of an ice pick — remembers her mother with an ice pick twenty years ago, raising it to jam it down into a piece of ice — dreams of an ice pick raised in her two trembling hands and brought down hard into whose chest? — his chest? — but what about the wispy light-brown hairs of his chest, which she supposedly loves?

4

Hips grinding, jammed together. You might imagine music in the background, the grinding is so fierce. An ancient bed: brass bedstead. It came with the house. A semi-furnished old farmhouse with a restored chimney! The one time her lover ventured into her own home, her husband’s handsome white Cape Cod, he clowned around and peeked into drawers nervously, joking about hidden tape recorders and other ingenious spying devices he’d just read about in a national newsmagazine, and then, serious with a sudden manly frown, he told her he had to leave, he couldn’t make love to her there, in her husband’s bed, that magical marriage bed with the satin bedspread.

Why not?

A manly code, a masculine code she couldn’t appreciate, maybe?

Now she lies with him in his own rented bed, an old farmhouse bed with a brass headboard, and she sees at the back of his skull a shadowy area like a fatal shadow in an x-ray. Secret from her. Their toes tickle one another. Twenty toes together at the foot of the bed, under the khaki cover! Such loving toes! But the shadow inside his head isn’t loving; she fears it growing bigger, darker; she shuts her eyes hard to keep it from oozing into her own skull, because she has always tried to be optimistic about life.

5

Ducks on the river. Mallards. Male and female in pairs and in loose busy groups, Canadian geese bouncing on the waves, going one way in a large confederation of birds, then turning unaccountably and going the other way, back and forth across the choppy waves, back and forth, their calls strident and dismal as she runs, her brow furrowed with some strange stray memory of her mother and an ice pick —

He, the husband, took the Volkswagen to the airport and left her the Buick. I’ll call you from New York, he said. Darkness at the back of his skull. If his drinking got too bad and he really got sick, she would abandon her lover and nurse him. If he killed himself she would abandon her lover and wear black. Years of mourning. Guilt. Sin. If he found out about her lover and ran over and killed him, shot him right in that bed, she would wear black, she would not give evidence against him, she would come haggard to court, a faithful wife once again.

The husband will not get sick, will not kill himself, will not kill the lover or even find out about him; he will only grow old.

She will not need to wear black or to be faithful. She will grow old.

The lover will not even grow old: he will explode into molecules as into a mythology.

6

I don’t know him at all.

A stormy river, small cataclysms. Quakes, spouts, whirlpools a few yards deep. She doesn’t dare to look at the water because her mind might suddenly go into a spin.

You take things too seriously before dawn.

Climbs up the path to his house, up the back way to his meager one-acre farm, Feet already wet from a lifetime of puddles that must be glimpsed far ahead of time in order to be avoided, and suddenly there is a blow against the back of her neck, she pitches forward, a man’s feet stumble with her feet, she cries out at the sight of large muddy boots — The blow is so hard that her teeth seem shaken loose. She is thrown forward and would fall except he has caught hold of her.

Jerks her around to face him.

Small panicked screams. She hears someone screaming feebly — hears the sounds of toil, struggle — the man, whose face she can’t see, trips her neatly with one ankle behind hers, she falls on her right side, on her hip and thigh and shoulder, already she is scrambling to get away — trying to slide sideways, backward in the mud — but the man has gripped her by the shoulders and lifts her and slams her back against the ground again, up, and then down again, as if trying to break her into pieces, and she sees a swirl of eyes, yellow-rimmed, the small hard dots of black at the center of each eye somehow familiar and eternal, even the dried mucus at the inside corner of each eye absolutely familiar, eternal —

A body jammed against hers. A bent knee, the strain of his thigh muscles communicated to her body, his wheezing, panting, his small cries overpowering hers, his grasping, nudging, glowering face, his leathery skin jammed against her skin; I don’t know him at all, the bridge of his nose suddenly very important, lowered to her face again and again. Tufts of pale hair in his ears, swollen veins in his throat, his eager grunts, his groveling above her, the stale fury of his breath, his hands, his straining bent knees, the cold mud, the lead-gray patch of sky overhead; inch by inch she is being driven up the hill by his love for her, his thudding against her in a rapid series of blows that jar her entire body and seem to have loosened the teeth in her head —

7

Once by chance but not really by chance she had met her lover in the general store in town, where he had a post-office box to insure his anonymity (exaggerating the world’s interest in him, he imagined a crowd of curious friends sailing up the Hudson to claim him). That rushed exchange of hellos, that eager snatching of eyes, smiles, The anxiety: Am I still loved? Adultery makes people nervous. She saw that he hadn’t shaved and was disappointed. They whispered between shelves of soup cans and cereal boxes and jars of instant coffee, the brand names and their heraldic colors and designs so familiar that she felt uneasy, as if spied upon by old friends. Her husband was at the lumberyard to buy a few things and would only be a few minutes, she had no time to waste; backing away, she put out her hands prettily as if to ward off her eager lover, and he, unshaven, dressed in a red-and-black checked wool jacket, took a step toward her, grinning, Why are you so skittish? Between the towering shelves of fading, souring food he lunged at her with his face, kissed her lips, more of a joke than a true kiss, and she felt a drop of his saliva on her lips and, involuntarily, she licked it off, and the drop was swept along by the powerful tiny muscles of her tongue, to the back of her throat, and down in a sudden pulsation of secret muscles to her insides, where it entered her bloodstream before she had even laughed nervously and backed away, paid for her jar of Maxwell House instant coffee and a leaky carton of milk, hurried outside without glancing back, walked over to the lumberyard where her husband was standing in a brightly lit little office made of concrete blocks talking with a fat man in a red-and-black checked wool jacket; by now the drop of saliva was soaring along her bloodstream, minute and bright and stable as a tiny balloon, rushing through the veins to the right ventricle — I don’t know you at all — and faster and faster into the pulmonary artery, and into the secret left side of the heart, where it inflated itself suddenly, proudly, and caused her heart to pound —

Did you get the things you wanted? her husband asked.

8

Late winter. Freezing air. A car parked on the river bank, by the edge of the big park — barbecue fireplaces with tiny soiled drifts of snow on their grills, you have to imagine people at the picnic tables, you have to imagine a transistor radio squealing, and the smell of burning charcoal; but you can still see the re- mains of Sunday comics blown into the bushes.

She turns, twists herself eagerly in his arms. His mouth rubs against hers damply, the lips seem soft but they are also hard, or maybe it is the hardness of his youthful teeth behind them. Desperation. Struggle. The toiling of their breaths. On the radio is wxs1’s “Sunday Scene,” a thumping tumult of voices and their echoes, yes, everything is wonderful — everything is desperate — he begins his frantic nudging, they are both eighteen, she discovers herself lying in the same position again, making the same writhing sharp twists with her body, as if fending him off and inviting him closer, she moves in time with the music, and then they are sitting up again and he is smoking a cigarette like someone in a movie. Small fixed uneasy smiles. They will marry, obviously.

9

Early spring. Freezing air. The heater in his car won’t work right. State Police find lovers dead in an embrace. They kiss each other wetly, hotly, eagerly on the lips, they slide their bodies out of their clothes, snakelike, eager and urgent, the man’s breath is like a hiss, the woman’s breath is shallow and seems to go no farther than the back of her throat, he lifts her legs up onto the front seat again, onto the scratchy plastic seat cover; such a difficult trick; after all, they are a lot older than eighteen.

10

A woman in a long blue dress. Her stockings white cotton; her shoes handmade. The man in a waistcoat, holding her hand, slipping down the incline to the river bank, They turn to each other eagerly and embrace. So friendly! So helpful! They kneel in the grass, whispering words that can’t be heard by the children who are hiding in the bushes. The lovers undress each other. The woman is shy and efficient, the man keeps laughing in small nervous embarrassed delighted spurts, and the children in the bushes have to stand up to see more clearly what is happening —

11

In his bed, before dawn, she notices the grimy blanket that she will think about with shame, hours later, and as he kneels above her she senses something fraudulent about him, no, yes, but it is too late; she grips his back and his legs though she is exhausted, and her constricted throat gives out small, gentle, fading, souring sounds of love, but she feels the toughness of his skin, like hide, and the leathery cracks of his skin, and down at his buttocks the cold little grainy pimples, like coarse sandpaper, and one hand darts in terror to his head as if she wanted to grip the hair and pull his head away from hers, and she feels his loosening hair — Ah, clumps of his thick brown hair come away in her hand! I love you, he is muttering, but she seems to recognize the pitch and rhythm of his voice, she has heard this before, in a movie perhaps, and now, as they kiss so urgently, she tries not to notice the way his facial structure sags, dear God, the entire face can be moved from one side to the other, should she mention it? And he didn’t bother shaving again. He could have shaved before going to bed, guessing, hoping she might come this morning, before dawn. . . The eyeballs can be pushed backward . . . and then they move slowly forward again, springing slowly forward, in slow motion, not the way you would expect eyeballs to spring forward. . .

12

God, her body aches. There is an itchiness too, probably an infection. That tiny bubble in the blood, exploding into splashes of excited colorless water, probably infected. His swarming germs, seed. The stain on her clothes.

At home, upstairs in the white Cape Cod, she cleans herself of him outside and inside.

No, she is not cleaning herself of him, but preparing herself for him: a shower the night before, the glimpse of her flushed face in the steamy mirror, the sorrow of those little pinched lines about her breasts, the urgent, slightly protruding bone of her forehead, wanting to push ahead to the next morning and through the impending sleepless night beside her husband. She has caught insomnia from him during the eleven years of their marriage.

No, she is not preparing herself for anyone. She is simply standing in the bathroom staring at herself. The bathtub with the bluebells on the shower curtain. Put the shower curtain on the outside of the tub when you take a bath, on the inside when you take a shower, her mother has explained for the hundredth time. Why are you always in a daze? What are you daydreaming about, may I ask? No, not daydreaming. She is just staring in the mirror at her small hard breasts, at the disappointing pallor of her chest, at her stomach where the faint brown hairs seem to grow in a circle, in a pale circle around her belly button. She is fourteen years old. She is just staring in the mirror, reluctant to leave the bathroom; she is not preparing herself for anyone, she is just standing on the fluffy blue rug from Woolworth’s, she is not thinking about anything at all, she is reluctant to think.

13

Eight years old, the man finds himself again at a kitchen table, he glances up in surprise to see that it is the kitchen of his parents’ house, and he is reduced in size — no more than eight years old! It’s a rainy day and from the sound of the house (his father in the cellar) it must be a Saturday. He’s fooling around with his clay kit. He has made four snakes by rolling clay between his hands; now he twists the snakes into circles, heads mashed against tails, and makes a pot, but it doesn’t look right — too small. The clock is whirring above the stove: a yellow-backed General Electric clock. He is alone in the kitchen. His father is sawing something in the cellar and his mother is probably out shopping. He mashes all the clay together again and makes a column, about six inches high, and he molds the column into a body. With a pencil he pricks holes for the eyes and fashions a smiling mouth, pinches a little nose out, on the chest he pinches out two breasts, makes them very large and pointed, and between the legs he pokes a hole, Sits staring at this for a few minutes, He is aware of his father in the cellar, aware of the clock whirring, the rain outside, and suddenly a raw, sick sensation begins in him, in his bowels, and he is transfixed with dread. . . . He picks up a tiny piece of clay and makes a small wormlike thing and tries to press it against the figure, between her legs. It falls off. Perspiring, he presses it into place again and manages to make it stick. It is a small grub-sized thing but it makes sense. He stares at it and his panic subsides, slowly. He feels slightly sick the rest of the day.

14

He crouches above her, she notices his narrowed, squinting eyes, the hard dark iris, the tension of his mouth, and he buries his face against her shoulder and throat as if to hide himself from her, oh, she loves him, oh, she is dying for him, no one but him. Their stomachs rub and twist hotly together and she feels herself gathered up in his arms, is surprised at how small her body is, how good it is to be small, gathered in a man’s strong arms, and she thinks that the two of them might be lying anywhere, making love anywhere, the walls of this farmhouse might fall away to show them on a river bank, in the sunshine, or in a car, at the edge of a large state park with Dixie cups blowing hollowly about them as they love, and small white plastic spoons in the grass. . . .

Suddenly exhausted, her hands stop their caressing of his back as if a thought had occurred to them, she instructs herself to caress him again but her fingers seem to have lost interest, grown stiff as if with arthritis, what is wrong? At the back of her throat she feels a ticklish sensation as if she is going to cough, but instead of coughing she whispers I love you, involuntarily, and they are toiling upstream on the cold river, ducks and geese around them sadly, morosely; the lead-gray sky and the lead-gray water are enough to convince them that this act is utterly useless, but who can stop? On the grass a few feet away is her wide-brimmed straw hat, a hat for Sunday in the country, and he has not had time to take off his waistcoat, and his whiskers scratch her soft skin; but when he whispers Am I hurting you? she answers at once No, no, you never hurt me. Someone calls out to them, A mocking scream. A shout. They freeze together, wondering if they heard correctly — what was that? Someone is shouting.

It isn’t in their imaginations, it isn’t the cry of geese on the river, no, someone is really shouting at them — has her husband followed her here after all? — but no, it is a stranger who seems to know them. He stomps right over to them and they fall apart, dazed and embarrassed, they are so awkward together, being strangers themselves. The glaring lights make them squint. This stranger eyes them cynically. He squats, a more experienced lover, and arranges and rearranges arms, legs, the proper bending of the knee; with the palm of his practiced hand he urges the man’s head down, down, just a few inches more, yes, hold it like that; he spreads the woman’s hair in a fan around her head, a shimmering chestnut-brown fan, newly washed, and with his thumb he flecks something off her painted forehead — a drop of saliva, or a small leaf, or sweat from her lover’s toiling face — yes, all right, hold this — now he backs away and the glare of the lights surrounds them again. Behind the lights is a crowd, in fact crowds of people, an audience, jostling one another and standing on tiptoe, elbowing one another aside, muttering and impatient. Bring that camera in close! In close! The itching raw reddened flesh between the woman’s thighs, the moisture and the patch of hair, so forlorn with dampness, a monotonous detail; the camera itself slows with exhaustion and lingers too long upon this close-up, lacking the wit to draw back swiftly and dramatically. The woman with the hair fanned out around her head wonders if her make-up is smeared again, or if that slimy sensation is her skin coming loose. Someday, she knows, her skin must come loose and detach itself from her skull. So tired! She must not yawn. Must not. Must not even. swallow her yawn because the tendons of her throat will move and her lover will notice and be hurt. Or angered. His whiskers rub against her face, her mouth and nose. She hates his whiskers. It is sickening how hair grows out of men’s faces, constantly, pushing itself out… . There are tiny bits of hair on her lips. Here is marriage. Permanent marriage, she thinks. And he is whispering to her — Am I hurting you? and her pain fades as she realizes that she does love him and that though he hurts her, constantly and permanently, she must always whisper no, numb and smiling into his face, their bodies now comradely, soldierly in this grappling, their mouths hardened so that they are mainly teeth — the flesh seems to have rotted away — and she whispers no, you’re not hurting me, no, you have never hurt me.