Interviews

Self-Serving Writing is the Only Writing You Can Trust

Chelsea Martin and Juliet Escoria talk about mining your most painful memories

Chelsea Martin is funny. That point isn’t debatable. She’s been reliably funny for four books now, dating back to 2009 when she was a measly twenty-three years old. Like her four previously published books, Caca Dolce (her first book classified under “nonfiction”) is, unsurprisingly, hilarious — the kind of book that literally makes you LOL.

Her previous works have all been ultra-concise, with lots of things left unexplained and plenty of white space on the page. I always enjoyed this about her writing: its subtlety and pared-down aesthetic. Caca Dolce, however, is different — and in a good way. In these essays, Martin is bold and unflinching, poking and prodding at herself and her memories and motivations. She’s got a lot of material to mine: the time her mother started dating her father’s brother; the time she blocked her father’s emails, which came from addresses like stopbeingcrazychelsea@hotmail.com; the time she dug through her own vomit for a superglued-on fake tooth; her diagnosis, as an awkward high schooler, of Tourette’s. A lesser writer would tell these stories as cute anecdotes, and the result would have been a funny, perfectly enjoyable book. But these essays go further than that, probing deeply into not just Martin’s own experiences but what these experiences say about more complex themes such as place, class, and identity. Because of this, Caca Dolce doesn’t fall into that often-cited pitfall of the genre as being mere “navel gazing,” and is instead incredibly nuanced, relatable, and wholly distinctive.

We conducted this “conversation” via a Google doc, spanning the leisurely course of six weeks.

Juliet Escoria: Your book covers a pretty good chunk of time, from your childhood to your early 20s. How did you select which memories to include? Also, what is your first memory?

Chelsea Martin: Yeah, it’s a pretty long time span to cover. The collection as a whole covers a few thematic elements in life (money, sexuality, art, family) and my changing views about them as I grew up. And I don’t mean “themes” as in, like, a literary device or some way to frame my experiences to make them consumable. These are just the things I most commonly think about and have dealt with. The themes of my life. I thought it was important to tell the stories that show how those views changed over time.

My first memory is climbing into a kitchen cabinet to hide from my Nana and eat a PB&J. What’s yours?

I know the novel you’re working on now has your name in the title — Juliet the Maniac. I’m wondering if it is autobiographical at all? I’m curious because I think we’ve both drawn inspiration from our own lives in our work, but have taken liberties wherever the fuck we want with zero explanation. Writing about myself in a truthful way was deeply horrifying on many levels, and I’m wondering if you can relate?

JE: Mine was sitting in the basement with my mom during a tornado when we lived in Ohio.

Yes, it’s autobiographical, as is most everything I write, to some degree. I’ve written a small handful of “personal essays” and I learned that I don’t really understand the difference between writing fiction and writing nonfiction. In the essays, I felt more compelled to not make up entire scenes or embellish things, but it was really hard to not make shit up. I guess I’m just a natural liar.

There’s a stage during every book I’ve written where I feel like, WHAT AM I DOING, WHY AM I PUBLISHING THIS, THESE ARE ALL MY WORST THOUGHTS AND EXPERIENCES YET I AM SHARING THEM WITH STRANGERS??? I’m having it right now, going through edits from [our shared agent] Monika — this realization in the form of MS Word comment bubbles that, yes, somebody I don’t know that well has read this thing I made. I’ve been wondering if there is something wrong with me. Do you think there’s a certain masochism in your writing? A lot of the essays seem to cover really uncomfortable territory, such as your relationship with your dad and your stepfather. What was the most uncomfortable part?

CM: Oh god, yeah. So masochistic. I read from Caca for the first time at this event yesterday and literally had to tune myself out because I was so ashamed of myself for getting into a situation where I’m talking about this private awful experience in front of 30 strangers.

But I guess I didn’t see the point in attempting memoir if I wasn’t going to be painfully honest. And to me that meant telling stories that made me hate myself or that I thought made me look bad or weak. It does feel unhealthy. It’s not a nice experience to put yourself through.

One thing I didn’t consider when I started Caca Dolce was that writing about an experience extends the story line of whatever you’re writing about into the present.

So, like, the hardest thing about writing about my stepdad, for example, is that I have always presented myself as someone who didn’t care about him or want love from him. He’s been nothing but an antagonist in my life, and I’ve always had a “Fuck you, loser” attitude towards him. But in writing about it, I proved that I did care, and that I was very hurt that he did not love me, and that I’m still dealing with that pain, even after not speaking with him for a decade.

It’s humiliating. You expect this kind of project to be cathartic, but it actually causes more problems and discomfort.

One thing that helps me feel better is remembering that no one gives a shit.

I’m curious what kind of things you tend to want to make up in your writing?

I didn’t see the point in attempting memoir if I wasn’t going to be painfully honest. And to me that meant telling stories that made me hate myself or that I thought made me look bad or weak.

JE: In Black Cloud, the two most fictional stories were based on very real fears of mine, things I had imagined for myself and fixated on. In the novel, it’s been more like a choice between providing the reader with a bunch of not very interesting factual anecdotes that point to what I’m trying to say, in favor of making something up that gets the idea across very quickly in what is hopefully a memorable way. Fiction is nice like that. What Tim O’Brien said in The Things They Carried about emotional vs. literal truth.

I’ve always been curious if writing about this stuff is cathartic or not. I go back and forth with it making me feel more damaged than before, and then feeling sort of disassociated with the events I’m writing about in a way that feels productive — in 12-step speak, coming to a place where I don’t “regret the past, nor wish to shut the door on it.” Kind of what you said, that it extends the storyline into my present. This thing was a part of my past, and now I’ve been able to turn it into a book. (This ‘healthiness’ is often temporary.)

I feel like if you had come to that realization about your stepfather in therapy, your therapist would be real proud of you, like, “Good job, Chelsea. You identified that cause of that pain.” But does knowing where it come from really help us? One of my therapists fixated on the fact that my mother was depressed when I was young, and that was nice to think about — that maybe my feelings of being a freak as a child, which I previously viewed as having no explanation, actually didn’t come out of nowhere after all. But I don’t know if that knowledge has helped me any. Sometimes I wonder if maybe I reject the “writing as catharsis” idea simply because it sounds corny to me and seems to cheapen a person’s work, as though it has a self-serving purpose. What do you think? Did you ever go to therapy for this shit?

CM: One of my professors in college told me that if you want to be a writer, the first thing you need to do is go to therapy and work out your dumb shit. I guess so that your work isn’t bogged down with figuring out your dumb shit. It seemed like good advice. But no, I haven’t really done therapy. I went a few times as a kid, and then I did it for a year in college when I had insurance that covered it. I can imagine that therapy could be good, and I would try it again, but I’ve had only annoying experiences with it so far.

I don’t really buy into the idea that you can identify causes of your behavior or whatever. I don’t mean that to belittle anyone’s progress in therapy. If you can find a way to frame an experience to make yourself change or feel better, then hell yeah. But everything is so complicated and the mind is so fallible and I think it’s weird to pretend you can figure anything out. My stepdad was a stupid little bitch — that much I know. I’m absolutely sure he affected my life and my personality profoundly, in both negative and positive ways. I could venture a guess, and say that living with someone who I felt smarter than at a very young age probably gave me confidence in my own intelligence. But I don’t know. Maybe it had the opposite effect, or a completely different, unexpected effect. It feels literally impossible to know.

I agree with you that ‘writing as catharsis’ sounds bad, like you’re having a breakthrough with your dumb shit in public and no one cares. But I am also not really interested in writing that isn’t self-serving. Like if a writer isn’t writing for themselves, to work something out or ask a difficult question or discuss something they’re obsessed with, then who/what are they doing it for? For strangers? For money/success/attention? Seems like the definition of selling out, man.

If a writer isn’t writing for themselves, to work something out or ask a difficult question or discuss something they’re obsessed with, then what are they doing it for?

I guess, to me, the point of writing memoir (or fiction about real experiences) is to find something valuable in something you thought had no value. Sounds corny af but maybe not as corny as this: I think memoir can also really help other people feel okay about their own experiences. Finding something to relate to can be a very big deal. When I was going through shit with my dad, and considering cutting him out of my life permanently, I looked everywhere for stories about people who had gone through this. I was looking for permission, because I truly didn’t know if it was acceptable to do that. But I didn’t find many stories about it at all. So what if my story could be the permission someone needed to cut someone shitty out of their life?

And even if it’s not a big life-changing thing like that, it can be really cool to relate about something you weren’t expecting to relate to. There is a part in Jessi Klein’s memoir, You’ll Grow Out of It, about preparing to get married, and she thinks she’s really down to earth and is just gonna get a simple, cheap wedding dress. But then her friend doesn’t like the dress she picks and she second guesses herself and tries to find something else. The longer she looks, the more seriously she takes it, until she’s about to buy this very expensive fancy dress that is the opposite of what she originally wanted/intended. I’ve never been in that situation, but it struck me as the type of situation I would definitely get myself into, but I hadn’t realized that about myself before in that particular way. So that’s another thing I like about memoir.

The Upside of Losing Everything

JE: I agree with all of that 100%. My mom being depressed surely affected me, but it didn’t cause anything to happen or not happen. And I agree about the necessity of writing being self-serving to a degree. I try to make books I would want to read. One reason why I wanted to write this novel is because most books about the same subject matter (a teenager’s experiences with mental illness, self-destruction, and being institutionalized) ring false to me, to some degree, or are very different than what I experienced. The only example I can think of that really compared was The Bell Jar, and Esther is older than fictional Juliet, much less interested in making trouble, and, of course, there’s 40 years separating them (my novel takes place in the late ‘90s).

You told me in an email that some people wanted you to change your book from essays to a memoir. Why was the essay form important to you? What essays and memoirs do you think of as being similar to Caca Dolce, or had elements that you admired?

CM: When my agent and I were shopping the collection to publishers, a few editors suggested that I reorganize Caca Dolce into a memoir. I guess a memoir is more sellable, kind of like how novels sell better than story collections. I don’t really get it, but people say that. So basically they wanted me to break apart the stories to make a single, more cohesive story line.

What I felt I would lose if I restructured it was the way I was able to let each story have its own set of rules, its own headspace, and its own specific age, without interfering with any other story’s needs. For example, I have an essay about my teeth which briefly encapsulates the lifetime of my tooth problem. The teeth stuff wasn’t super interesting as it happened in real time: having braces as a teen, having congenitally missing lateral incisors, the fact that my hometown was infamous for people not having all their teeth, wearing a retainer with two plastic teeth attached to it to make it look like I had a full set of teeth.

I mean, I guess some of that was interesting. But it didn’t make a story, in my opinion, until the moment in the essay when I lost one of my plastic retainer teeth, and faced my entire history of teeth issues — all the stigma and fear and desperation — while in the warehouse of a chocolate shop. I felt that story could only work as an essay, with its own way of dealing with time and experience, and outside of the rules of the other stories. So I’m very happy that I ended up with Soft Skull and that my editor, Yuka Igarashi, didn’t make me do that!

I was initially inspired to start the project after reading Michael Ian Black’s You’re Not Doing it Right and watching Mike Birbiglia’s My Girlfriend’s Boyfriend. I really admired the way they could tell all these different stories with varying perspectives, while moving through a single larger story line. And they’re both really funny and that’s important to me, too.

I was also thinking a lot about female essay collections by people like Emily Gould, Sloane Crosley, Lena Dunham, and Chloe Caldwell, which I love for being so honest and vulnerable but simultaneously feel alienated by, because my experience seems so far outside of theirs. So I thought it would be an interesting challenge to use a similar form and aesthetic to tell a different kind of story. Which seems really similar to your reasoning for telling a different kind of mental illness story. It’s kind of funny to think of feeling alienated as a reason to expose your deepest vulnerabilities lol.

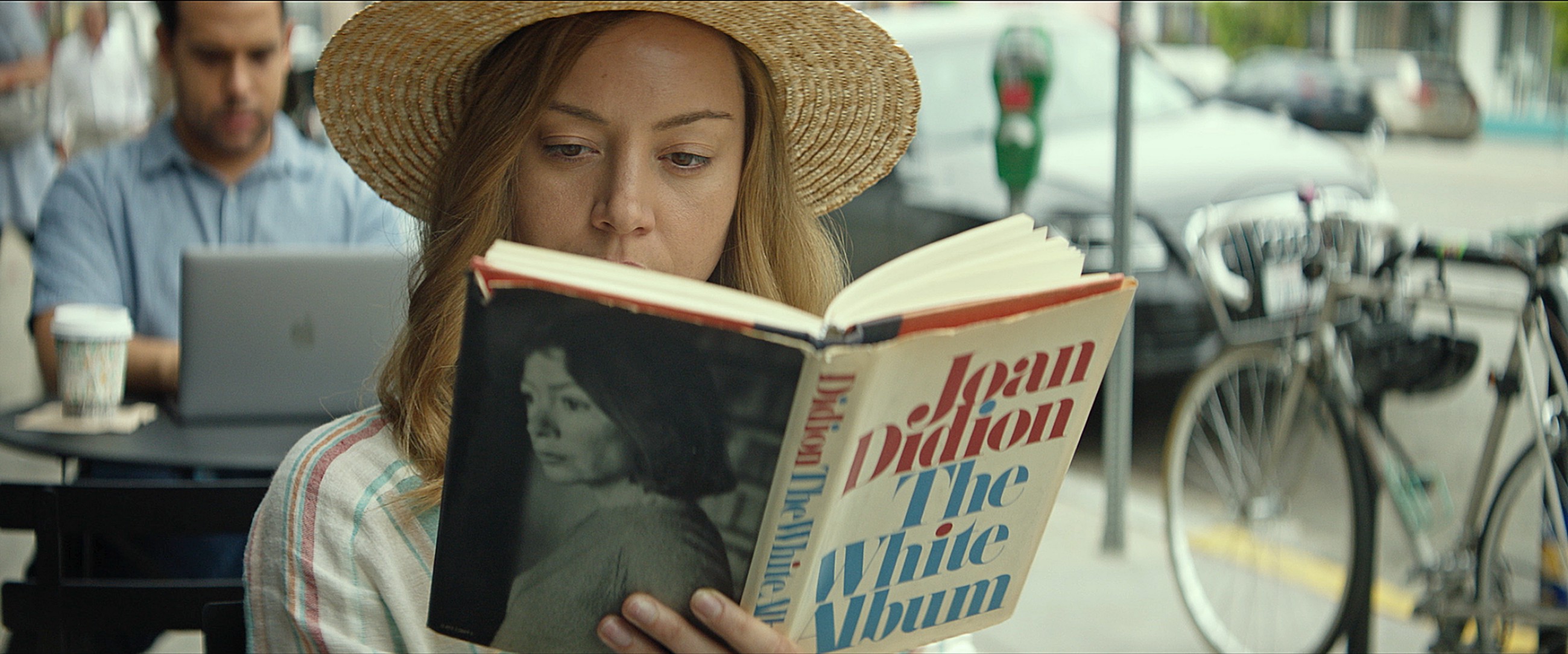

Do you read a lot when you’re in the middle of a big project?

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

JE: Honestly, no. When I’m really wrapped up in writing, I don’t read much at all, because I’m so occupied, both in terms of headspace and just actual time, with my own work. When I have downtime, I want to do something dumb like play Bubble Witch 3 or look at Sephora or read about the burning shithouse that is our country.

Lately I’ve been reading contemporary books that are similar to mine in subject matter — The Girls, Girls on Fire, How to Start a Fire and Why, Panopticon — and they’re making me feel both better and worse than my own book. It is likely hubris/self-centeredness, but I’m 83% sure that my book is better than those books, which makes me feel good. (Panopticon is the best of these books btw.) But it also makes me feel bad, because my book is so not like these books. I think that might actually be a good thing but I’m not sure. Also, the majority of those books were written by nice people imagining what it’s like to be a demented teenage girl and that offends me on a spiritual level.

I’ve always been curious but never asked about the formation of your company Universal Error. I know you run it with your boyfriend Ian and your BFF William, who are both “characters” in Caca Dolce and people you met in art school. I have no idea who the other people on Universal Error’s “Contact” page are. Who are they? How did you guys decide to make this company? How does this work fit in with your writing? Also, how do Ian and William feel about becoming characters in a book?

CM: Universal Error is a shape-shifting entity that changes at my convenience. I started it with my long-time BFF William but he lost interest, so Ian and I run it now. We sell cards and zines and buttons and things like that. Sometimes we work with other artists and writers to make things. Those are the other people listed on the contact page. Most recently, Universal Error was given a grant to hold a zine fest in Spokane.

I’ve always self-published zines and little books of my work, so UE is a natural outlet for that. I think it’s really cool to put something together from start to finish, and to be able to present your work how you want. And it’s cool to be able to make a little money from it.

Ian said he likes being a character in my book. He said I wrote nice things about him, which I guess is true. William hasn’t read it yet. One interesting thing about William is that the only books he’s read in the last eight years have been ones I wrote.