Interviews

Sex Workers Take on Gentrification and Evil Landlords in “Hot Stew”

Booker Prize-finalist Fiona Mozley on how there are no ethical choices in capitalism

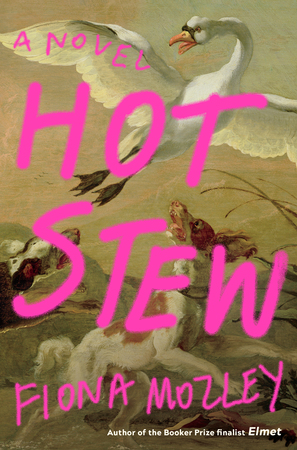

Fiona Mozley’s sophomore novel Hot Stew focuses on the unlikely intersection of a whole cast of diverse characters whose lives constitute the hustle and bustle and grit of contemporary Soho in London. There are homeless communities, there are old drunks, there are young businessmen, there are sex workers, there are developers, there are those who resist. The “big bad” is gentrification: developer Agatha wants to get the sex workers out of one of her Soho properties so she can better monetize it. This is a novel about solidarity among the dispossessed, and about holding on to what is good about the old when the new threatens to paint over everything with its matte, rich gloss.

English writer Fiona Mozley triumphantly emerged on the literary world stage at the age of 29 when her debut novel Elmet was short-listed for the 2017 Man Booker Prize. Elmet is a “northern Gothic” set in rural Yorkshire, and focuses on the claustrophobic relationship between a father and his two children, and their disputes over land and property. Hot Stew is an entirely different kettle of fish, but Mozley’s concern with property, place, and development remains central.

I talked with Mozley over Skype, she in Scotland, and me in Australia; neither of us in Soho.

Madeleine Gray: You’re a white woman who is Oxbridge educated, and one of the main characters, Precious, is a Black woman, not tertiary educated, and a sex worker. What are your thoughts on what authors can and can’t do with characters whose experiences they do not share?

FM: So, the first thing was, because it’s a multi-voice narrative set in London, it would have been beyond bizarre for all of those characters to be white. So after I’d made that decision, I decided, okay, well, I didn’t just want the peripheral characters to be people of color. So I decided to make some of the more integral characters people of color. Then I just focused on the things about them that I felt able to describe and imagine. Precious doesn’t face issues of race in the book because when you write characters, you only ever write a bit of them, don’t you? There’s never a complete story. So I just focused on the bits which I felt pertain to the novel in a way that I could get to grips with—and the parts of those characters’ lives with which I didn’t feel able to get to grips with, I didn’t write about. I suppose I felt I would have written about them poorly.

I find these questions and these conversations so interesting and so important, but I think part of it is actually just trying to make the best of it, try to do what you can, try to take on board these valuable points and try to be aware that you may fall short and that there may be criticisms and those are valid and potentially part of the conversation.

MG: Okay, so as you said, you don’t do the bits of the characters that you feel you can’t access. For Precious, who is a Black sex worker, this means you don’t paint her Blackness as something that detrimentally affects her in this line of work, like she doesn’t experience any racialized objectification or violence. And for the other sex workers in this book, too, they seem to have no problems apart from development and gentrification.

FM: I wasn’t really interested in showing the sex work per se, because it’s not what the book’s about. I didn’t want to gloss over the fact that a lot of sex workers have a really, really hard time, but I also didn’t want these sex workers, these characters, to experience the hard times. I wanted these women to have a really good situation and for their main difficulties to be socio-economic and their main struggles to do with money and housing.

I felt that it was necessary to mention other set-ups, like how a lot of sex workers in the UK are trafficked, but again, this novel is all very artificial, this is a fictional vision. For me, it was first and foremost about treating the characters as human beings, working out their lives in terms of their relationships, not their work. We don’t focus very much on Bastian’s work, for example. So, again, the thrust of the novel was property, this dispute and the struggle over a piece of land.

MG: Why did you choose Soho as the setting?

Of all the cities that I’ve ever inhabited, it had to be London because London is the place where I’ve seen the most profound divisions between rich and poor.

FM: I thought about setting it in a bunch of different places, but it just seemed to me of all the cities that I’ve ever inhabited, it had to be London because London is the place where I’ve seen the most profound divisions between rich and poor. And it’s a place in the UK where those forces are happening most frenetically, where gentrification is at its apex, and particularly Soho, because it has this history of being this Bohemian quarter and it’s been various things over the years. It’s been a place where immigrants have gone in the 19th-century, it’s got a lot of political connections, Karl Marx lived there, and it’s also been the center of the theater district, a food district, and sex work district. It’s a real melting pot, I suppose, for want of a better word. So it seemed like a really good place to set it. Also I ended up living in London for four months in 2013 in an illegal sublet, kind of like Glenda, and that was when I was writing Elmet and thinking about Hot Stew.

MG: The character of the Archbishop, the ringleader of a group of homeless people in Soho, is very interesting to me. If you wanted the sex workers in your novel to have a generally good time because you wanted gentrification to be their only problem, then your decision to characterize the “leader” of a large homeless population as pretty much evil is an interesting move. He’s almost Trumpian in his illogical rhetorical sway. What was going on here?

FM: I wanted him to represent almost the spirit of London, but not in a good way. I wanted him to be this demon at the heart of the city. And he talks about how he claims to be 300 years old and it’s all very surreal. He claims to have lived in connection with all these historical characters and he’s given Karl Marx his best ideas and he sat for Joshua Reynolds and all of Casanova’s stories are actually the Archbishop’s. So I wanted a sense of this demon at the heart of the city that’s been living there for centuries and who’s been whirling various forces around him and he now finds himself in this basement preying on vulnerable people trying to collect them together and whip them up into a frenzy. In some respects, I saw that as the play within a play, even though it’s not a play, it’s a novel. There is no play.

MG: Yes, you wrote a novel.

FM: But there’s this extra layer of artifice, I suppose. The homeless community finds this crown in the rubble, which turns out to be a theater prop but they don’t know it’s a theater prop. And so I wanted this connection to an almost Shakespearean tragedy figure, who is whirling these forces around him and then he comes to his ultimate demise. And I suppose I’m really interested in the pettiness of power. With the Archbishop we can watch him doing his thing and just think, “Oh, what’s it all for?” And I think that always applies, whether you’re in charge of a Soho basement or whether you’re in charge of the United States of America. I mean, I wasn’t actually thinking of Trump but it works, doesn’t it? The same pettiness, the same pointlessness to it all, the same dark energy.

MG: Absolutely. But then for Agatha, the developer who wants to get the sex workers out of her building, her want of power comes from a similar but also such a desperate place. Tell us about what motivates Agatha’s desire for power.

The whole novel is about being slowly eaten alive whilst you’re trying to also consume.

FM: I don’t even think she necessarily wants power. I think she’s terrified. I think she’s terrified of other people, she’s terrified of being found out or cast out. I mean, her own sisters are after her. She’s really worried about revolution and rioting. She’s incredibly lonely, but I think her desire for power and is a desire for control. I’m quite interested in the role that fear has in that mindset. She’s definitely the arch villain but I suppose when there were moments when I wanted to humanize her, I wanted to present this idea of terror and fear and loneliness, which, I suppose, is a well-trodden path when we’re thinking about what makes powerful, rich villainous people tick. There is this idea that we can come back to the place of vulnerability. But I am genuinely interested in that because I’m interested in the way that it might be possible to get through that, rescue those people from themselves even if they don’t really deserve it.

MG: Evil people are going to read your book and then change their minds because they’ll understand their own vulnerability.

Moving on! Hot Stew is very plot-y but it also plays so much with language and metaphor and simile, and on this note: I’ve noticed that you’re obsessed with snails. There’s this bit that I liked when Bastian’s putting in his AirPods and your narrator says, “The earphones fit snugly. The plastic beads like tiny snails curled in their shells.” I love that image. But the novel also begins with a snail, and then there are snails all throughout it. What’s with the snails?

FM: I wanted to start the novel from the smallest character and then let it all unfurl. And, of course, the snail is a curly thing, isn’t it? So it has this idea of slowly unspooling, and that snail there was about to get eaten and the whole novel is about being slowly eaten alive whilst you’re trying to also consume. So it’s about, I guess, the “autophagy” of capitalism. [Fiona here wanted me to make clear that she was using air quotes and making fun of herself when she used the word “autophagy”. She was, this is true.]

And snails obviously carry their homes on their backs and so much of the novel is about home. In a lot of medieval books, people used to write in the margins, and one of the recurring motifs are snails and snails get up to all sorts of things. There are snails who joust each other and are dressed up as knights. People have tried to work out why the snail is such a motif in the marginalia but snails have this association of being in the margins and I suppose I wanted to evoke that.

MG: Speaking of movement from the margins: your first novel was shortlisted for the Booker Prize when you were 29 and it hadn’t even been published yet. How did that experience shape the trajectory of your career but also your attitude to writing? And, as a follow-up, what are your thoughts on literary prizes: good or bad?

FM: So, it had a profound effect on me. It meant that I just had a career overnight. Elmet was never supposed to do that. So it completely changed my life! But I really wanted to make the most of the platform that Elmet gave me.

And in terms of literary prizes, it’s a difficult one for me because I would be nowhere without them. Elmet was nominated for quite a few other prizes as well and it completely projected me into a world that I wouldn’t otherwise have inhabited. Do I think that literature should be about competition? No, I don’t, but I can’t detach my own good fortune from the prizes that Elmet was long listed and short listed for.

There are no ethical choices in capitalism. You have to be absurdly successful or from a rich background to be in a position to refuse prize money.

That being said, it’s also really funny when I think about where the money for prizes comes from. But it’s this thing, isn’t it? There are no ethical choices in capitalism. You have to be an absurdly successful author or someone from a really rich background to be in a position to refuse prize money. And with the Booker particularly, you find yourself rubbing shoulders with all sorts of people at those dinners, and I’m very much one for making the most of all encounters and all conversations. So if I happen to be sitting next to a hedge fund manager or, indeed, a Tory peer who sits in the House of Lords, then I’m going to subtly make the most of that conversation. But it is always strange looking at the authors and their politics and then the people who are also sitting at the dinners and funding the prize and their politics.

MG: What do you hope to have done with this book? What do you want readers to take from it?

FM: I mean, I’d love it if people did more reading around the politics of sex work and the politics of gentrification. If you’re someone that already knows a huge amount about gentrification and the politics of sex work, you may find this book totally bland and uninteresting. But I think, I hope, that there will be lots of people who read this book who are interested in the world around them but maybe haven’t really thought about some of the themes that it explores. And I do hope that they maybe think about it more.

In fact, I have actually already had that response from readers who’ve said it really made them think their own assumptions about sex workers. And I think that’s a good thing. I just think that novels are important in exploring human connections and human motivations and extending empathy.

MG: Yes! You can often feel like a bit of a humanistic loser for having that view, but I believe it too.

FM: Yeah, exactly. But it’s true, isn’t it?