essays

Shame and Ridicule in Indiana: William H.

S

Where is Indiana? Forget geography; if you can say with confidence if it’s located to the east or west of the Mississippi, you’re ahead of the curve. No, I’m thinking of mythology, that America of Madison Avenue and Sunset Boulevard, the Alamo and Antietam. In this spiritual landscape, Indiana isn’t misunderstood. It’s ignored.

John Jeremiah Sullivan described the state’s placelessness in “The Final Comeback of Axl Rose,” his essay about one of Indiana’s favorite sons.

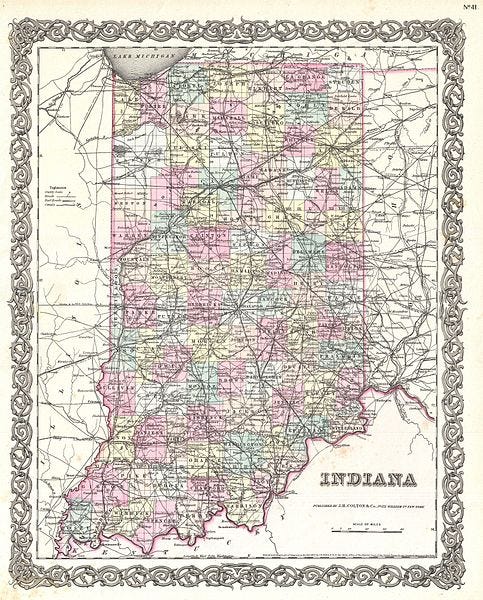

Given the relevant maps and a pointer, I know I could convince even the most exacting minds that when the vast and blood-soaked jigsaw puzzle that is this country’s regional scheme coalesced into more or less its present configuration after the Civil War, somebody dropped a piece, which left a void, and they called the void “central Indiana.” I’m not trying to say there’s no there there. I’m trying to say there’s no there. Think about it; get systematic on it. What’s the most nowhere part of America? The Midwest, right? But once you get into the Midwest, you find that each of the different nowherenesses has laid claim to its own somewhereness. There are the lonely plains in Iowa. In Michigan there’s a Gordon Lightfoot song. Ohio has its very blandness and averageness, faintly comical, to cling to. All of them have something. But now I invite you to close your eyes, and when I say ‘Indiana’ … blue screen, no? And we are speaking only of Indiana generally, which includes southern Indiana, where I grew up, and northern Indiana, which touches a Great Lake. We have not even narrowed it down to central Indiana. Central Indiana? That’s like, “Where are you?” I’m nowhere. “Go there.”

I’ve lived in Indiana for much of my life, and can attest to the veracity of Sullivan’s characterization. If you had asked what I thought of my home state, I would have answered that I don’t think much about it. This can be an advantage, at least for a writer. Whereas other regions may have demanded my attention — asking insistently what I thought of their landscapes, histories, and dialects — Indiana let my imagination wander. I could explore the particularities of my own inner reality, its variety belying the relative blankness of my external circumstances. I looked to books, movies, and TV to populate this reality, and every so often, I came across a story that took place in Indiana. It was oddly reassuring to have my state’s existence confirmed by prime time television. Eerie, Indiana was possibly the most prominent example, a TV show from the early 90s that was like The X-Files for kids. Its fantastical nature confirmed what I had intuited: Indiana was what you made of it.

Recently, however, Indiana’s blankness has given way to notoriety. This past March, Governor Mike Pence signed into law the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The particulars of this law have been well-covered. Suffice it to say, the law used innocuous, vaguely upbeat language, as laws are wont to do, that would have made permissible a host of discriminatory actions against gay and lesbian residents of the state. Same-sex marriage was legalized here last year, a move that angered certain legislators and residents, and RFRA appears to have been designed to give those legislators and residents a loophole that would have allowed them to ignore the ruling. In a sense, Pence as the governor was relating to the state not unlike the way I have as a writer, taking the blankness of Indiana and refashioning it to serve his own needs. And to a degree, he was successful.

Overnight, Indiana went from being the middle child of the Middle West to the First Church of Evil and Intolerance. “#BoycottIndiana!” implored my Twitter and Facebook timelines, and at first I was onboard, ready to attempt the seemingly physically impossible feat of boycotting myself. I was ashamed, and doubly so. I am a Hoosier and a Christian, having been raised in an evangelical, homeschooled subculture that has thrived in Indiana for decades. I used to believe being gay was a sin, and wasn’t disabused of the notion until I went to college, a Christian one, and made friends who were gay, and whose devotion put mine to shame. Everyone was saying the worst things about Indiana, and I was inclined to agree.

Soon, however, I saw that there were many residents who disagreed, vehemently, with RFRA and its implications. There were major protests in downtown Indianapolis. Mayor Greg Ballard, a Republican, implored Gov. Pence to repeal the law and help restore the city’s reputation as a desirable site for business and tourism. The Indianapolis Star ran a front-page editorial that asked Pence, in 100-point font, to FIX THIS LAW. Plenty of Hoosiers were angry. So why were my social media accounts wallpapered with #BoycottIndiana rather than, say, #RecallRFRA? Why did the entire state become a metonym for the worst impulses of certain of its citizens?

I looked for answers, as I usually do, in literature. Admittedly, literature has a better track record of asking questions than giving answers. But questions can be more telling, and so I turned to a few writers who have considered the question of the nowhere that is Indiana.

***

William H. Gass’s “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” is not just one of my favorite stories about Indiana. It’s one of my favorite stories ever. In the annals of literary history, if Indiana were known for nothing else than inspiring this meditation on heartbreak and loneliness, that would be more than enough to assure its relevance.

Gass wrote the story in the early 1960s when he was living in Brookston and teaching at nearby Purdue University. The narrator refers to it as B, “a small town fastened to a field in Indiana.” We learn little about the narrator’s personal life; the one salient detail he offers is that he is “in retirement from love,” having recently ended a relationship with a woman who haunts his narration, appearing suddenly at the ends of sentences. There is no plot to speak of, the story of the narrator’s life having effectively ended. Instead, the narrator records a series of notes about B, its citizens, habits and customs.

PEOPLE

In the cinders at the station boys sit smoking steadily in darkened cars, their arms bent out the windows, white shirts glowing behind the glass. Nine o’clock is the best time. They sit in a line facing the highway — two or three or four of them — idling their engines. As you walk by a machine may growl at you or a pair of headlights flare up briefly. In a moment one will pull out, spinning cinders behind it, to stalk impatiently up and down the dark streets or roar half a mile into the country before returning to its place in line and pulling up.

Throughout the story, the implicit question is this: are the people of B inherently sad and lonesome, or do they appear as such to the narrator because he is sad and lonesome? It’s almost as if the narrator is a magnet and the people are iron filings, snapping into formation as soon as he brings his attention to bear upon them. Places that lack definition can be eager to be defined, no matter how.

But in defining the particulars of B, the narrator also defines himself, and this is what gives the story its power, the willingness to have his identity bound up with Indiana. Even before RFRA, Indiana had been something of a catch-all for Middle American backwardness, as in Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. It’s a mostly delightful show, peopled with characters who first appear stereotypical, but soon acquire depth and idiosyncrasy. The exception to that, however, are the residents of Kimmy’s hometown of Durnsville, IN. Everyone there is either stupid or incompetent, or both. Its depiction of Midwesterners was offensive, I guess, but it honestly didn’t offend me. It bored me. It was lazy, unwilling to find anything to relate to in the lives and personalities of small-town Hoosiers.

Gass’s narrator frequently finds the residents of B to be crude and slovenly, but he doesn’t push them away. He draws them closer, their crudeness and slovenliness becoming his own. The best way to get to know oneself, he suggests, is to get to know one’s neighbors.

This Midwest. A dissonance of parts and people, we are a consonance of Towns. Like a man grown fat in everything but heart, we overlabor; our outlook never really urban, never rural either, we enlarge and linger at the same time, as Alice both changed and remained the same in her story. You are blond. I put my hand upon your belly; feel it tremble from my trembling. We always drive large cars in my section of the country. How could you be a comfort to me now?

***

Everyone wants to claim David Foster Wallace. I often want to tell East Coast types to keep their hands off him, he belongs to the Midwest, but that would violate the core tenet of Midwestern politeness.

Wallace was raised in rural Illinois and spent significant chunks of his adult life in the region. He turned his attention to Indiana in “The Suffering Channel,” a novella-length story from the collection Oblivion. Where Gass considered the state on its own terms, Wallace toggles between rural Indiana and the New York media world, posing questions of celebrity, audience and which, exactly, is which.

It’s also a 90-page gross-out joke, delivered with fully committed deadpan blankness.

Skip Atawater is a journalist who was born and raised in Indiana. He now works for Style magazine (think People), writing for its WHAT IN THE WORLD? section, which covers unusual, even bizarre, human interest stories that still retain an upbeat angle. Atwater returns to his home state, to a small town east of Indianapolis, to interview Brint Moltke and his wife Amber. Brint possesses a quality you could call either a talent or a medical condition: he shits art. Literally. His bowel movements come out in the form of intricately detailed sculptures, which are then retrieved, lacquered and displayed, mostly at his home, but also at local 4-H fairs. Atwater thinks Moltke’s story is incredible and wants to write it up for Style, but his superiors worry that the subject matter, in all senses of the term, is far too nauseating for the magazine’s readers. Through a rather convoluted plot involving a new cable venture called the Suffering Channel, which loops “montages of photos involving anguish or pain,” Atwater wins over his superiors, and Moltke’s story runs in the issue of Style dated September 10, 2001.

What is Wallace trying to say with this? Is it a vision of the country as an enormous physical body, with New York as the brain and the Midwest as the digestive system? A disavowal of the cerebral, of the head, in favor of the gut? The closest thing to a thesis comes when Atwater is considering the “paradoxical intercourse of celebrity and audience” that informs every issue of Style:

It was more the deeper, more tragic and universal conflict of which the celebrity paradox was a part. The conflict between the subjective centrality of our own lives versus our awareness of its objective insignificance. Atwater knew — as did everyone at Style, though by some strange unspoken consensus it was never said aloud — that this was the single great informing conflict of the American psyche. The management of insignificance. It was the great syncretic bond of US monoculture. It was everywhere, at the root of everything — of impatience in long lines, of cheating on taxes, of movements in fashion and music and art, of marketing.

How to manage one’s insignificance? It’s a question everyone has to consider, though it may have a different inflection here in Indiana, where insignificance is sometimes assumed, by residents and observers both. You can follow the exploits of celebrities deemed as significant, retweeting their aphorisms and reblogging photo sets to experience a contact high from secondhand fame. You can make like Brint Moltke, expressing himself with the only resources he had at hand, resources that others might call waste. Perhaps I’m setting up a false binary. I’m lingering here, though, because I think this passage gets at the sense of insignificance that Gov. Pence and supporters of RFRA are experiencing. Yes, people are talking shit about Indiana. But at least they’re talking about it. People do stupid things to get attention all the time. Disagree with their actions, certainly, but I think any American could recognize and even empathize with the motives of Pence and his cohorts: the desire not to be ignored.

***

I want to close by considering a writer who examined a different brand of Indiana blankness. Etheridge Knight spent six years in an Indiana prison for robbery, the kind of outrageous sentence a black man would have taken as par for the course in the 1960s but today would seem — well, never mind.

Knight was marginalized in a marginal state. Even if he had tried to know himself by knowing his neighbors, it’s likely that his neighbors wouldn’t have let him do so. But the indifference he faced throughout his life didn’t embitter him, as he writes in “Birthday Poem,” composed in Indianapolis on April 19, 1975.

The sun rose today, and

The sun went down

Over the trees beyond the river;

No crashed thunder

Nor jagged lightning

Flashed my forty-four years across

The heavens. I am here.

I am alone. With the Indianapolis / News

Sitting, under this indiana sky

I lean against a gravestone and feel

The warm wine on my tongue.

My eyes move along the corridors

Of the stars, searching

For a sign, for a certainty

As definite as the cold concrete

Pressing against my back.

Still the stars mock

Me and the moon is my judge.

But only the moon.

’Cause I ain’t screwed no thumbs

Nor dropped no bombs —

Tho my name is naughty to the ears of some

And I ain’t revealed the secrets of my brothers

Tho my balls’ve / been pinched

And my back’s / been / scarred

And I ain’t never stopped loving no / one

O I never stopped loving no / one

Only the moon can judge Indiana. It’s a state that mostly gets ignored, and occasionally ridiculed, by the rest of the country, but no matter. Anyone is welcome to come here and see a reflection of themselves in the unlikeliest places, no matter what any law says.