Books & Culture

Soft Men with Hungry Hearts

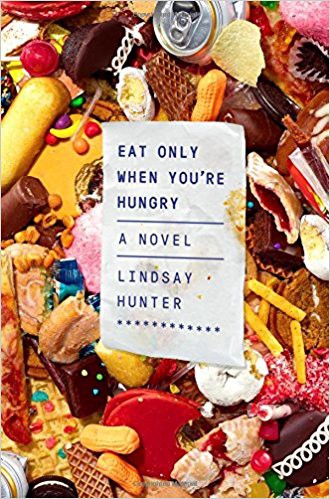

Fatness, addiction, and self-denial in Lindsay Hunter’s ‘Eat Only When You’re Hungry’

Our culture does not love soft men. In Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, a tender barman named Biff Brannon feels himself to be both mother and father to everyone in a small Georgia town. To make this feeling tangible, he wants to adopt a couple of kids. “A boy and a girl,” he imagines; “in the summer the three of them would go to a cottage on the Gulf… and then they would bloom as he grew old.” But he owns that bar, has a demanding wife, plus is probably queer, and the calendar reads sometime in the 1920s. Biff does not get his wish.

Stephen Sondheim’s musical Into the Woods also opens with wishes. A baker and his wife wish for a child, but they can’t have one because the Baker had a shitty father who earned a curse that follows the whole family line. In the Baker’s best number, “No More,” Baker Senior appears and sings, “We disappoint, we leave a mess, we die, but we don’t.” Fathers of tender men die hard, it seems. Or they weren’t around — the Baker sings back, “No more curses you can’t undo left by fathers you never knew.” The Baker’s wish for a baby comes true, but to get it, he has to lose his wife. The consequences of wishing are always dear, we learn, even fatal.

The consequences of wishing are always dear, we learn, even fatal.

I was negative 57 years old when McCullers’ book punched its way onto the literary scene, and negative one when the curtain went up for Sondheim, but a raw and raging twelve when Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Magnolia found its way into the dusty off-brand video store in my Chelsea neighborhood. “I’m sick and I’m in love,” wails William H Macy’s character, a gay quiz kid all grown up, as the bar patrons, men who keep their feelings on lockdown, look on in horror. “I do have a lot of love to give,” he says later, sitting on a gas station trash can and his face covered in blood. “I just don’t know where to put it.”

Thunkity thunk, went some knock of revelation and recognition. Here was a brand new thing, yet I’d felt it myself: a sense of wrongness, that something in your gender and your body and your way of being does not match up with what the world requires or will allow. The video store owner, which mostly stocked gay porn and regarded my portly posterior with real confusion, was all too happy to let me keep Magnolia for many, many months.

Lindsay Hunter’s Eat Only When You’re Hungry is a welcome addition to the miniature curio cabinet of works centering male tenderness, softness, vulnerability, and yearning. The novel’s crackling core is Greg, a fat, hungry, sexual, alcoholic father who embarks on a lonely and lazy cross-state voyage in a rented RV to find his drug-addicted son, Greg Junior — GJ.

As I read I dog-eared the pages that called me out or taught me something new about parenthood, marriage, addiction, family dysfunction, food compulsion, hunger, the body, the texture of objects, or the American South, but soon I had to stop it. Every other page was getting folded.

The RV seemed made for men like him, men whose asses needed room to spread, men whose backs zinged at the sight of a golf club. The driver’s seat was as wide as two seats in the Volvo, skinned a plush gray something or other, and felt four feet deep with cushion. The headrest stayed out of his way but was at the ready whenever Greg needed cradling.

Could I love this description of Greg any more? I could not. (Relatedly, see my thoughts on male frump as an aesthetic, which also includes Biff and the Baker). Could Greg hate himself any more? He could not. Comfort, spreading, cradling — these are things that Greg does not allow himself in his regular life with his sturdy and shut-down wife, Deb. “Hair pinned back out of her eyes,” Hunter writes of Deb. “Purse snug under her arm. Nothing worrisome, nothing out of place.” Yet just on the other side of the Deb coin is his ex-wife Marie, an untidy curly-haired woman who drinks too much and likes to fuck, facts about which Greg feels profound ambivalence. And could he love his son, GJ, a smart, sensitive kid who likes camping and lets other boys drink out of the bottle before he does, any more? He could not. (That camping flashback, where we learn that GJ is truly an unsalvageable addict … break my heart into glittering smithereens, why don’t you, Lindsay Hunter).

Greg’s universe is polarized, populated by only two kinds of people: those whose hungers eat them alive (Greg, his son GJ, his father, his ex-wife Marie) and those who lock theirs up and swallow the key but are able to live normal, if fundamentally sad, lives (Deb, his father’s girlfriend Lydia).

Luke Goebel Talks With Lindsay Hunter

If a family is a gradual loosening, a journey from denial to acceptance with the passing generations, Hunter skillfully sets up Greg’s son GJ, the quest object of this book, as the opposite of Greg’s own parents. His parents are a grey sky and his son is a tornado and he sits somewhere in the middle, ping-ponging back and forth between restriction and indulgence, between too much feeling and too little. The way parents both love and hurt their own children in precisely the same ways is perhaps this book’s most devastating illumination, and just simply how terrifying and random and loving and terrifying again it is to be a parent. “Y-ball. T-ball. Pop Warner. Tap dance (Marie’s idea),” writes Hunter in one of two stylistically innovative mini-chapters that add zing to the whole book. “Crayons, markers, paints. Charcoal. Spray paint. Skateboard. Body board. Beach summers. Sky-blue swimming pools. Hotels. Resorts. Camping. Hamburgers, pizza, hot dogs, ice cream.” These are all the things we buy and give to our kids because what else is there to do but try to love and offer them things. And then, a few lines later: “Big gulps. Beer. Whisky. Dope. Hash. Tar. Rocks. Spoon, needle. Pipe. Darkness. Light. I’m sorry. It’s okay. Theft. Shouting.” These are things we make with them, and the other things we gave them.

The way parents both love and hurt their own children in precisely the same ways is perhaps this book’s most devastating illumination.

In my fat processing group, we are often grappling with a gap between the fat positivity movement, which reminds us that being fat is a body characteristic like being tall or redheaded, and the reality of the air we breathe everyday, which equates flesh with failure and teaches fat people to hate not only our own bodies, but also our hunger — our needs, wishes, desires, feelings, and very guts. Though Hunter herself is surely aware of fat positivity and fat acceptance, Greg is not — all the book allows him when it comes to his body is hatred and shame, feelings meant unequivocally to slosh over into how we understand his feelings towards all desire and vulnerability in general. It’s a choice on Hunter’s part that feels both disappointing and true.

The strategies Greg’s parents and his wife practice do not work. This much is clear by the end of the book. GJ’s strategies do not work. His appetites have eaten him alive , as hunger denied is wont to do. This kind of extreme black-and-white thinking feels bang-on for an addict and the child of addicts, which Greg’s son is—and, which we learn in the final pages of the book, Greg also is. He goes to bring his son back, to save his kid from the clutches of insatiable need and out-of-control desire, but the person he ends up saving, of course, is himself — but by the end of the book we readers are hungering for some sort of middle ground.

As political actors, we want to practice the most liberating and idealistic thinking and behavior, but as humans we are flawed, stuck, cruel, damned, busy, poor, programmed, and oppressed. Greg’s mother didn’t eat and didn’t feed him; the seeds of equating need with weakness began there. Yet it doesn’t feel outside the bounds of good art to wonder if Hunter might have explored other perspectives towards fatness, hunger, and shame through the wishes of her other, equally glittering, supporting characters.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

One glimmer of this that Hunter does offer is expansive possibilities as to how to deal with an addicted or self-destructive child beyond enabling or condemning. Greg’s father’s girlfriend Lydia smokes crack with her addict daughter so she can empathize. Greg himself decides to listen, to self-examine, and to love.

One important feature of my childhood what my father called “the automatic no.” To hear him tell it, my sister always said “no” to any request he or my mother might make of her: no to setting the table, no to picking up milk, no to seeing some new doctor who would surely cure her, once and for all, of her fatness. To hear my sister tell it, her “no” was a necessary corrective to the power of Our Father, to whose dictatorial demands and senseless moods we had been submitting for all of time. If my sister was the one who always said “no,” I was the one who — if I spoke at all — always said “yes.” From my bedroom, I listened to my sister and my father do battle. Our apartment rattled with endless things and their opposites — it’s like this, no it’s like that; yes you will, no I won’t.

After years, you start to leave rooms, leave lovers, leave cities from no discernible motivation, just to see if you can.

But here is what I have found out: To live in the automatic no is to block the process that happens when you say “yes” or “no” by choice, and start to move towards or away from things on purpose. After years, you start to leave rooms, leave lovers, leave cities from no discernible motivation, just to see if you can. You become unable to say “yes” and mean what “yes” means: come closer. These days, I’m trying not to pingpong back and forth, but instead sit lost, homesick, and ill, in the middle. For me, this has been growing up.

It’s Biff who closes McCullers’ book, alone in the bar, after all the other characters have left.

His heart turned and he leaned his back against the counter for support. For in a swift radiance of illumination he saw a glimpse of human struggle and of valor. Of the endless fluid passage of humanity through endless time. And of those who labor and of those who — one word — love. His soul expanded. But for a moment only. For in him he felt a warning, a shaft of terror. Between the two worlds he was suspended… Between bitter irony and faith. Sharply he turned away.