Lit Mags

Stone Animals

A short story by Kelly Link, recommended by Lincoln Michel

Introduction by Lincoln Michel

Since her debut collection in 2001, Link has blurred genre boundaries, mixed YA and adult literary fiction, and published stories about zombies and witches in mainstream literary magazines. This genre-mixing is increasingly popular in the literary world but few, if any, writers are able to mix these elements into fiction as startlingly original as the stories of Kelly Link. And she’s been doing it since before it was cool.

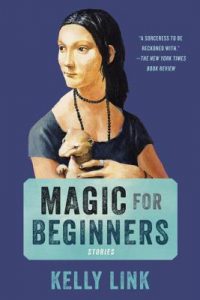

This week sees the release of Get in Trouble, Link’s first adult book in nearly a decade (she published a YA story collection, Pretty Monsters, in 2008). You should, of course, buy it and devour. However, the story I’m recommending comes from her second collection, Magic for Beginners. Like most of her stories, “Stone Animals” is hard to classify yet impossible to forget. It’s a ghost story without any ghosts, domestic realism in which the domestic is unreal.

Ostensibly, “Stone Animals” follows a husband, a pregnant wife, and their two children as they settle into a new house in the suburbs. Henry still has to commute to the city to work, and Catherine is left at home to fix up the house while Carleton and Tilly run wild. There are dinner parties, late work hours, and unending paint options for the walls. There are no murders or monsters. Nothing explicitly horrifying happens.

And yet.

“Stone Animals” is brimming with Gothic terror and uncanny unease. Link immediately sets the reader on unsure footing. We do not even know the question that starts the story, though we can guess:

“Henry asked a question. He was joking.

‘As a matter of fact,” the real estate agent snapped, ‘it is.’”

As the family explores their new life, Link’s writing recalls the films of David Lynch in its ability to imbue everyday objects with terror. If the house is haunted, the haunting is not found in grand, Gothic architecture or secret chambers. The haunting is in the banal objects of everyday life. The TV, the car, even bars of soap. It’s an American dream turned dark and strange: Kafka in Cheever’s clothing.

What entities are haunting or what this haunting entails, is, like so much else, unclear.

Reality itself is unstable. Dreams blur into waking life. Objects become other objects. Are the titular stone animals dogs or lions or rabbits? The family is unsure. Drawings of trees turn into rabbits, and in dreams the rabbits become skyscrapers. Even the boss’s rubber band ball looks “like some kind of eyeless, hairless, legless animal. Maybe a dog. A Carleton-sized dog…”

“Stone Animals” is thick with meaning — psychoanalytically inclined readers can have a field day — yet resistant to simple interpretation. The story transforms as you look at it, in the same way that Link’s fiction expertly moves between genres and resists simple forms.

Is the house haunted? Is Tilly becoming a rabbit? Is Henry going to war with the neighbors? The reader is left with many questions and only one answer: Kelly Link is magic.

–Lincoln Michel

Online Editor, Electric Literature

Stone Animals

Kelly Link

Share article

“Stone Animals” by Kelly Link

Henry asked a question. He was joking.

“As a matter of fact,” the real estate agent snapped, “it is.”

It was not a question she had expected to be asked. She gave Henry a goofy, appeasing smile and yanked at the hem of the skirt of her pink linen suit, which seemed as if it might, at any moment, go rolling up her knees like a window shade. She was younger than Henry, and sold houses that she couldn’t afford to buy.

“It’s reflected in the asking price, of course,” she said. “Like you said.”

Henry stared at her. She blushed.

“I’ve never seen anything,” she said. “But there are stories. Not stories that I know. I just know there are stories. If you believe that sort of thing.”

“I don’t,” Henry said. When he looked over to see if Catherine had heard, she had her head up the tiled fireplace, as if she were trying it on, to see whether it fit. Catherine was six months pregnant. Nothing fit her except for Henry’s baseball caps, his sweatpants, his T-shirts. But she liked the fireplace.

Carleton was running up and down the staircase, slapping his heels down hard, keeping his head down and his hands folded around the banister. Carleton was serious about how he played. Tilly sat on the landing, reading a book, legs poking out through the railings. Whenever Carleton ran past, he thumped her on the head, but Tilly never said a word. Carleton would be sorry later, and never even know why.

Catherine took her head out of the fireplace. “Guys,” she said. “Carleton, Tilly. Slow down a minute and tell me what you think. Think King Spanky will be okay out here?”

“King Spanky is a cat, Mom,” Tilly said. “Maybe we should get a dog, you know, to help protect us.” She could tell by looking at her mother that they were going to move. She didn’t know how she felt about this, except she had plans for the yard. A yard like that needed a dog.

“I don’t like big dogs,” said Carleton, six years old and small for his age. “I don’t like this staircase. It’s too big.”

“Carleton,” Henry said. “Come here. I need a hug.”

Carleton came down the stairs. He lay down on his stomach on the floor and rolled, noisily, floppily, slowly, over to where Henry stood with the real estate agent. He curled like a dead snake around Henry’s ankles. “I don’t like those dogs outside,” he said.

“I know it looks like we’re out in the middle of nothing, but if you go down through the backyard, cut through that stand of trees, there’s this little path. It takes you straight down to the train station. Ten-minute bike ride,” the agent said. Nobody ever remembered her name, which was why she had to wear too-tight skirts. She was, as it happened, writing a romance novel, and she spent a lot of time making up pseudonyms, just in case she ever finished it. Ophelia Pink. Matilde Hightower. LaLa Treeble. Or maybe she’d write gothics. Ghost stories. But not about people like these. “Another ten minutes on that path and you’re in town.”

“What dogs, Carleton?” Henry said.

“I think they’re lions, Carleton,” said Catherine. “You mean the stone ones beside the door? Just like the lions at the library. You love those lions, Carleton. Patience and Fortitude?”

“I’ve always thought they were rabbits,” the real estate agent said. “You know, because of the ears. They have big ears.” She flopped her hands and then tugged at her skirt, which would not stay down. “I think they’re pretty valuable. The guy who built the house had a gallery in New York. He knew a lot of sculptors.”

Henry was struck by that. He didn’t think he knew a single sculptor.

“I don’t like the rabbits,” Carleton said. “I don’t like the staircase. I don’t like this room. It’s too big. I don’t like her.”

“Carleton,” Henry said. He smiled at the real estate agent.

“I don’t like the house,” Carleton said, clinging to Henry’s ankles. “I don’t like houses. I don’t want to live in a house.”

“Then we’ll build you a teepee out on the lawn,” Catherine said. She sat on the stairs beside Tilly, who shifted her weight, almost imperceptibly, towards Catherine. Catherine sat as still as possible. Tilly was in fourth grade and difficult in a way that girls weren’t supposed to be. Mostly she refused to be cuddled or babied. But she sat there, leaning on Catherine’s arm, emanating saintly fragrances: peacefulness, placidness, goodness. I want this house, Catherine said, moving her lips like a silent movie heroine, to Henry, so that neither Carleton nor the agent, who had bent over to inspect a piece of dust on the floor, could see. “You can live in your teepee, and we’ll invite you to come over for lunch. You like lunch, don’t you? Peanut butter sandwiches?”

“I don’t,” Carleton said, and sobbed once.

But they bought the house anyway. The real estate agent got her commission. Tilly rubbed the waxy, stone ears of the rabbits on the way out, pretending that they already belonged to her. They were as tall as she was, but that wouldn’t always be true. Carleton had a peanut butter sandwich.

The rabbits sat on either side of the front door. Two stone animals sitting on cracked, mossy haunches. They were shapeless, lumpish, patient in a way that seemed not worn down, but perhaps never really finished in the first place. There was something about them that reminded Henry of Stonehenge. Catherine thought of topiary shapes; The Velveteen Rabbit; soldiers who stand guard in front of palaces and never even twitch their noses. Maybe they could be donated to a museum. Or broken up with jackhammers. They didn’t suit the house at all.

“So what’s the house like?” said Henry’s boss. She was carefully stretching rubber bands around her rubber band ball. By now the rubber band ball was so big, she had to get special extra-large rubber bands from the art department. She claimed it helped her think. She had tried knitting for a while, but it turned out that knitting was too utilitarian, too feminine. Making an enormous ball out of rubber bands struck the right note. It was something a man might do.

It took up half of her desk. Under the fluorescent office lights it had a peeled red liveliness. You almost expected it to shoot forward and out the door. The larger it got, the more it looked like some kind of eyeless, hairless, legless animal. Maybe a dog. A Carleton-sized dog, Henry thought, although not a Carleton-sized rubber band ball.

Catherine joked sometimes about using the carleton as a unit of measure.

“Big,” Henry said. “Haunted.”

“Really?” his boss said. “So’s this rubber band.” She aimed a rubber band at Henry and shot him in the elbow. This was meant to suggest that she and Henry were good friends, and just goofing around, the way good friends did. But what it really meant was that she was angry at him. “Don’t leave me,” she said.

“I’m only two hours away.” Henry put up his hand to ward off rubber bands. “Quit it.We talk on the phone, we use email. I come back to town when you need me in the office.”

“You’re sure this is a good idea?” his boss said. She fixed her reptilian, watery gaze on him. She had problematical tear ducts. Though she could have had a minor surgical procedure to fix this, she’d chosen not to. It was a tactical advantage, the way it spooked people.

It didn’t really matter that Henry remained immune to rubber bands and crocodile tears. She had backup strategies. She thought about which would be most effective while Henry pitched his stupid idea all over again.

Henry had the movers’ phone number in his pocket, like a talisman. He wanted to take it out, wave it at The Crocodile, say, Look at this! Instead he said, “For nine years, we’ve lived in an apartment next door to a building that smells like urine. Like someone built an entire building out of bricks made of compressed red pee. Someone spit on Catherine in the street last week. This old Russian lady in a fur coat. A kid rang our doorbell the other day and tried to sell us gas masks. Door-to-door gas-mask salesmen. Catherine bought one. When she told me about it, she burst into tears. She said she couldn’t figure out if she was feeling guilty because she’d bought a gas mask, or if it was because she hadn’t bought enough for everyone.”

“Good Chinese food,” his boss said. “Good movies. Good bookstores. Good dry cleaners. Good conversation.”

“Treehouses,” Henry said. “I had a treehouse when I was a kid.”

“You were never a kid,” his boss said.

“Three bathrooms. Crown moldings. We can’t even see our nearest neighbor’s house. I get up in the morning, have coffee, put Carleton and Tilly on the bus, and go to work in my pajamas.”

“What about Catherine?” The Crocodile put her head down on her rubber band ball. Possibly this was a gesture of defeat.

“There was that thing. Catherine’s whole department is leaving. Like rats deserting a sinking ship. Anyway, Catherine needs a change. And so do I,” Henry said. “We’ve got another kid on the way. We’re going to garden. Catherine’ll teach ESOL, find a book group, write her book. Teach the kids how to play bridge. You’ve got to start them early.”

He picked a rubber band off the floor and offered it to his boss. “You should come out and visit some weekend.”

“I never go upstate,” The Crocodile said. She held on to her rubber band ball. “Too many ghosts.”

“Are you going to miss this? Living here?” Catherine said. She couldn’t stand the way her stomach poked out. She couldn’t see past it. She held up her left foot to make sure it was still there, and pulled the sheet off Henry.

“I love the house,” Henry said.

“Me too,” Catherine said. She was biting her fingernails. Henry could hear her teeth going click, click. Now she had both feet up in the air. She wiggled them around. Hello, feet.

“What are you doing?”

She put them down again. On the street outside, cars came and went, pushing smears of light along the ceiling, slow and fast at the same time. The baby was wriggling around inside her, kicking out with both feet like it was swimming across the English Channel, the Pacific. Kicking all the way to China. “Did you buy that story about the former owners moving to France?”

“I don’t believe in France,” Henry said. “Je ne crois pas en France.”

“Neither do I,” Catherine said. “Henry?”

“What?”

“Do you love the house?”

“I love the house.”

“I love it more than you do,” Catherine said, although Henry hated it when she said things like that. “What do you love best?”

“That room in the front,” Henry said. “With the windows. Our bedroom. Those weird rabbit statues.”

“Me too,” Catherine said, although she didn’t. “I love those rabbits.”

Then she said, “Do you ever worry about Carleton and Tilly?”

“What do you mean?” Henry said. He looked at the alarm clock: it was 4 a.m. “Why are we awake right now?”

“Sometimes I worry that I love one of them better,” Catherine said. “Like I might love Tilly better. Because she used to wet the bed. Because she’s always so angry. Or Carleton, because he was so sick when he was little.”

“I love them both the same,” Henry said.

He didn’t even know he was lying. Catherine knew, though. She knew he was lying, and she knew he didn’t even know it. Most of the time she thought that it was okay. As long as he thought he loved them both the same, and acted as if he did, that was good enough.

“Well, do you ever worry that you love them more than me?” she said. “Or that I love them more than I love you?”

“Do you?” Henry said.

“Of course,” Catherine said. “I have to. It’s my job.”

She found the gas mask in a box of wineglasses, and also six recent issues of The New Yorker, which she still might get a chance to read someday. She put the gas mask under the sink and The New Yorkers in the sink. Why not? It was her sink. She could put anything she wanted into it. She took the magazines out again and put them into the refrigerator, just for fun.

Henry came into the kitchen, holding silver candlesticks and a stuffed armadillo, which someone had made into a purse. It had a shoulder strap made out of its own skin. You opened its mouth and put things inside it, lipstick and subway tokens. It had pink gimlet eyes and smelled strongly of vinegar. It belonged to Tilly, although how it had come into her possession was unclear. Tilly claimed she’d won it at school in a contest involving donuts. Catherine thought it more likely Tilly had either stolen it or (slightly preferable) found it in someone’s trash. Now Tilly kept her most valuable belongings inside the purse, to keep them safe from Carleton, who was covetous of the precious things — because they were small, and because they belonged to Tilly — but afraid of the armadillo.

“I’ve already told her she can’t take it to school for at least the first two weeks. Then we’ll see.” She took the purse from Henry and put it with the gas mask under the sink.

“What are they doing?” Henry said. Framed in the kitchen window, Carleton and Tilly hunched over the lawn. They had a pair of scissors and a notebook and a stapler.

“They’re collecting grass.” Catherine took dishes out of a box, put the Bubble Wrap aside for Tilly to stomp, and stowed the dishes in a cabinet. The baby kicked like it knew all about Bubble Wrap. “Woah, Fireplace,” she said. “We don’t have a dancing license in there.”

Henry put out his hand, rapped on Catherine’s stomach. Knock, knock. It was Tilly’s joke. Catherine would say, “Who’s there?” and Tilly would say, Candlestick’s here. Fat Man’s here. Box. Hammer. Milkshake. Clarinet. Mousetrap. Fiddlestick. Tilly had a whole list of names for the baby. The real estate agent would have approved.

“Where’s King Spanky?” Henry said.

“Under our bed,” Catherine said. “He’s up in the box frame.”

“Have we unpacked the alarm clock?” Henry said.

“Poor King Spanky,” Catherine said. “Nobody to love except an alarm clock. Come upstairs and let’s see if we can shake him out of the bed. I’ve got a present for you.”

The present was in a U-Haul box exactly like all the other boxes in the bedroom, except that Catherine had written henry’s present on it instead of large front bedroom. Inside the box were Styrofoam peanuts and then a smaller box from Takashimaya. The Takashimaya box was fastened with a silver ribbon. The tissue paper inside was dull gold, and inside the tissue paper was a green silk robe with orange sleeves and heraldic animals in orange and gold thread. “Lions,” Henry said.

“Rabbits,” Catherine said.

“I didn’t get you anything,” Henry said.

Catherine smiled nobly. She liked giving presents better than getting presents. She’d never told Henry, because it seemed to her that it must be selfish in some way she’d never bothered to figure out. Catherine was grateful to be married to Henry, who accepted all presents as his due; who looked good in the clothes that she bought him; who was vain, in an easygoing way, about his good looks. Buying clothes for Henry was especially satisfying now, while she was pregnant and couldn’t buy them for herself.

She said, “If you don’t like it, then I’ll keep it. Look at you, look at those sleeves. You look like the emperor of Japan.”

They had already colonized the bedroom, making it full of things that belonged to them. There was Catherine’s mirror on the wall, and their mahogany wardrobe, their first real piece of furniture, a wedding present from Catherine’s great-aunt. There was their serviceable, queen-sized bed with King Spanky lodged up inside it, and there was Henry, spinning his arms in the wide orange sleeves, like an embroidered windmill. Henry could see all of these things in the mirror, and behind him, their lawn and Tilly and Carleton, stapling grass into their notebook. He saw all of these things and he found them good. But he couldn’t see Catherine. When he turned around, she stood in the doorway, frowning at him. She had the alarm clock in her hand.

“Look at you,” she said again. It worried her, the way something, someone, Henry, could suddenly look like a place she’d never been before. The alarm began to ring and King Spanky came out from under the bed, trotting over to Catherine. She bent over, awkwardly — ungraceful, ungainly, so clumsy, so fucking awkward, being pregnant was like wearing a fucking suitcase strapped across your middle — put the alarm clock down on the ground, and King Spanky hunkered down in front of it, his nose against the ringing glass face.

And that made her laugh again. Henry loved Catherine’s laugh. Downstairs, their children slammed a door open, ran through the house, carrying scissors, both Catherine and Henry knew, and slammed another door open and were outside again, leaving behind the smell of grass. There was a store in New York where you could buy a perfume that smelled like that.

Catherine and Carleton and Tilly came back from the grocery store with a tire, a rope to hang it from, and a box of pancake mix for dinner. Henry was online, looking at a jpeg of a rubber band ball. There was a message too. The Crocodile needed him to come into the office. It would be just a few days. Someone was setting fires and there was no one smart enough to see how to put them out except for him. They were his accounts. He had to come in and save them. She knew Catherine and Henry’s apartment hadn’t sold; she’d checked with their listing agent. So surely it wouldn’t be impossible, not impossible, only inconvenient.

He went downstairs to tell Catherine. “That witch,” she said, and then bit her lip. “She called the listing agent? I’m sorry. We talked about this. Never mind. Just give me a moment.”

Catherine inhaled. Exhaled. Inhaled. If she were Carleton, she would hold her breath until her face turned red and Henry agreed to stay home, but then again, it never worked for Carleton. “We ran into our new neighbors in the grocery store. She’s about the same age as me. Liz and Marcus. One kid, older, a girl, um, I think her name was Alison, maybe from a first marriage — potential babysitter, which is really good news. Liz is a lawyer. Gorgeous. Reads Oprah books. He likes to cook.”

“So do I,” Henry said.

“You’re better looking,” Catherine said. “So do you have to go back tonight, or can you take the train in the morning?”

“The morning is fine,” Henry said, wanting to seem agreeable.

Carleton appeared in the kitchen, his arms pinned around King Spanky’s middle. The cat’s front legs stuck straight out, as if Carleton were dowsing. King Spanky’s eyes were closed. His whiskers twitched Morse code. “What are you wearing?” Carleton said.

“My new uniform,” Henry said. “I wear it to work.”

“Where do you work?” Carleton said, testing.

“I work at home,” Henry said. Catherine snorted.

“He looks like the king of rabbits, doesn’t he? The plenipotentiary of Rabbitaly,” she said, no longer sounding particularly pleased about this.

“He looks like a princess,” Carleton said, now pointing King Spanky at Henry like a gun.

“Where’s your grass collection?” Henry said. “Can I see it?”

“No,” Carleton said. He put King Spanky on the floor, and the cat slunk out of the kitchen, heading for the staircase, the bedroom, the safety of the bedsprings, the beloved alarm clock, the beloved. The beloved may be treacherous, greasy-headed and given to evil habits, or else it can be a man in his late forties who works too much, or it can be an alarm clock.

“After dinner,” Henry said, trying again, “we could go out and find a tree for your tire swing.”

“No,” Carleton said, regretfully. He lingered in the kitchen, hoping to be asked a question to which he could say yes.

“Where’s your sister?” Henry said.

“Watching television,” Carleton said. “I don’t like the television here.”

“It’s too big,” Henry said, but Catherine didn’t laugh.

Henry dreams he is the king of the real estate agents. Henry loves his job. He tries to sell a house to a young couple with twitchy noses and big dark eyes. Why does he always dream that he’s trying to sell things?

The couple stare at him nervously. He leans towards them as if he’s going to whisper something in their silly, expectant ears.

It’s a secret he’s never told anyone before. It’s a secret he didn’t even know that he knew. “Let’s stop fooling,” he says. “You can’t afford to buy this house. You don’t have any money. You’re rabbits.”

“Where do you work?” Carleton said, in the morning, when Henry called from Grand Central.

“I work at home,” Henry said. “Home where we live now, where you are. Eventually. Just not today. Are you getting ready for school?”

Carleton put the phone down. Henry could hear him saying something to Catherine. “He says he’s not nervous about school,” she said. “He’s a brave kid.”

“I kissed you this morning,” Henry said, “but you didn’t wake up. There were all these rabbits on the lawn. They were huge. King Spanky–sized. They were just sitting there like they were waiting for the sun to come up. It was funny, like some kind of art installation. But it was kind of creepy too. Think they’d been there all night?”

“Rabbits? Can they have rabies? I saw them this morning when I got up,” Catherine said. “Carleton didn’t want to brush his teeth this morning. He says something’s wrong with his toothbrush.”

“Maybe he dropped it in the toilet, and he doesn’t want to tell you,” Henry said.

“Maybe you could buy a new toothbrush and bring it home,” Catherine said. “He doesn’t want one from the drugstore here. He wants one from New York.”

“Where’s Tilly?” Henry said.

“She says she’s trying to figure out what’s wrong with Carleton’s toothbrush. She’s still in the bathroom,” Catherine said.

“Can I talk to her for a second?” Henry said.

“Tell her she needs to get dressed and eat her Cheerios,” Catherine said. “After I drive them to school, Liz is coming over for coffee. Then we’re going to go out for lunch. I’m not unpacking another box until you get home. Here’s Tilly.”

“Hi,” Tilly said. She sounded as if she were asking a question.

Tilly never liked talking to people on the telephone. How were you supposed to know if they were really who they said they were? And even if they were who they claimed to be, they didn’t know whether you were who you said you were. You could be someone else. They might give away information about you, and not even know it. There were no protocols. No precautions.

She said, “Did you brush your teeth this morning?”

“Good morning, Tilly,” her father (if it was her father) said. “My toothbrush was fine. Perfectly normal.”

“That’s good,” Tilly said. “I let Carleton use mine.”

“That was very generous,” Henry said.

“No problem,” Tilly said. Sharing things with Carleton wasn’t like having to share things with other people. It wasn’t really like sharing things at all. Carleton belonged to her, like the toothbrush. “Mom says that when we get home today, we can draw on the walls in our rooms if we want to, while we decide what color we want to paint them.”

“Sounds like fun,” Henry said. “Can I draw on them too?”

“Maybe,” Tilly said. She had already said too much. “Gotta go. Gotta eat breakfast.”

“Don’t be worried about school,” Henry said.

“I’m not worried about school,” Tilly said.

“I love you,” Henry said.

“I’m real concerned about this toothbrush,” Tilly said.

He closed his eyes only for a minute. Just for a minute. When he woke up, it was dark and he didn’t know where he was. He stood up and went over to the door, almost tripping over something. It sailed away from him in an exuberant, rollicking sweep. According to the clock on his desk, it was 4 a.m. Why was it always 4 a.m.? There were four messages on his cell phone, all from Catherine.

He checked train schedules online. Then he sent Catherine a fast email.

Fell asleep @ midnight? Mssed trains. Awake now, going to keep on working. Pttng out fires. Take the train home early afternoon? Still lv me?

Before he went back to work, he kicked the rubber band ball back down the hall towards The Crocodile’s door.

Catherine called him at 8:45.

“I’m sorry,” Henry said.

“I bet you are,” Catherine said.

“I can’t find my razor. I think The Crocodile had some kind of tantrum and tossed my stuff.”

“Carleton will love that,” Catherine said. “Maybe you should sneak in the house and shave before dinner. He had a hard day at school yesterday.”

“Maybe I should grow a beard,” Henry said. “He can’t be afraid of everything, all the time. Tell me about the first day of school.”

“We’ll talk about it later,” Catherine said. “Liz just drove up. I’m going to be her guest at the gym. Just make it home for dinner.”

At 6 a.m. Henry emailed Catherine again.

Srry. Accidentally startd avalanche while puttng out fires. Wait up for me? How ws 2nd day of school?

She didn’t write him back. He called and no one picked up the phone. She didn’t call.

He took the last train home. By the time it reached the station, he was the only one left in his car. He unchained his bicycle and rode it home in the dark. Rabbits pelted across the footpath in front of his bike. There were rabbits foraging on his lawn. They froze as he dismounted and pushed the bicycle across the grass. The lawn was rumpled; the bike went up and down over invisible depressions that he supposed were rabbit holes. There were two short fat men standing in the dark on either side of the front door, waiting for him, but when he came closer, he remembered that they were stone rabbits. “Knock, knock,” he said.

The real rabbits on the lawn tipped their ears at him. The stone rabbits waited for the punch line, but they were just stone rabbits. They had nothing better to do.

The front door wasn’t locked. He walked through the downstairs rooms, putting his hands on the backs and tops of furniture. In the kitchen, cut-down boxes leaned in stacks against the wall, waiting to be recycled or remade into cardboard houses and spaceships and tunnels for Carleton and Tilly.

Catherine had unpacked Carleton’s room. Night-lights in the shape of bears and geese and cats were plugged into every floor outlet. There were little low-watt table lamps as well — hippo, robot, gorilla, pirate ship. Everything was soaked in a tender, peaceable light, translating Carleton’s room into something more than a bedroom: something luminous, numinous, Carleton’s cartoony Midnight Church of Sleep.

Tilly was sleeping in the other bed.

Tilly would never admit that she sleepwalked, the same way that she would never admit that she sometimes still wet the bed. But she refused to make friends. Making friends would have meant spending the night in strange houses. Tomorrow morning she would insist that Henry or Catherine must have carried her from her room, put her to bed in Carleton’s room for reasons of their own.

Henry knelt down between the two beds and kissed Carleton on the forehead. He kissed Tilly, smoothed her hair. How could he not love Tilly better? He’d known her longer. She was so brave, so angry.

On the walls of Carleton’s bedroom, Henry’s children had drawn a house. A cat nearly as big as the house. There was a crown on the cat’s head. Trees or flowers with pairs of leaves that pointed straight up, still bigger, and a stick figure on a stick bicycle, riding past the trees. When he looked closer, he thought that maybe the trees were actually rabbits. The wall smelled like Froot Loops. Someone had written Henry Is A Rat Fink! Ha Ha! He recognized his wife’s handwriting.

“Scented markers,” Catherine said. She stood in the door, holding a pillow against her stomach. “I was sleeping downstairs on the sofa. You walked right past and didn’t see me.”

“The front door was unlocked,” Henry said.

“Liz says nobody ever locks their doors out here,” Catherine said. “Are you coming to bed, or were you just stopping by to see how we were?”

“I have to go back in tomorrow,” Henry said. He pulled a toothbrush out of his pocket and showed it to her. “There’s a box of Krispy Kreme donuts on the kitchen counter.”

“Delete the donuts,” Catherine said. “I’m not that easy.” She took a step towards him and accidentally kicked King Spanky. The cat yowled. Carleton woke up. He said, “Who’s there? Who’s there?”

“It’s me,” Henry said. He knelt beside Carleton’s bed in the light of the Winnie the Pooh lamp. “I brought you a new toothbrush.”

Carleton whimpered.

“What’s wrong, spaceman?” Henry said. “It’s just a toothbrush.” He leaned towards Carleton and Carleton scooted back. He began to scream.

In the other bed, Tilly was dreaming about rabbits. When she’d come home from school, she and Carleton had seen rabbits, sitting on the lawn as if they had kept watch over the house all the time that Tilly had been gone. In her dream they were still there. She dreamed she was creeping up on them. They opened their mouths, wide enough to reach inside like she was some kind of rabbit dentist, and so she did. She put her hand around something small and cold and hard. Maybe it was a ring, a diamond ring. Or a. Or. It was a. She couldn’t wait to show Carleton. Her arm was inside the rabbit all the way to her shoulder. Someone put their little cold hand around her wrist and yanked. Somewhere her mother was talking. She said —

“It’s the beard.”

Catherine couldn’t decide whether to laugh or cry or scream like Carleton. That would surprise Carleton, if she started screaming too. “Shoo! Shoo, Henry — go shave and come back as quick as you can, or else he’ll never go back to sleep.”

“Carleton, honey,” she was saying as Henry left the room. “It’s your dad. It’s not Santa Claus. It’s not the big bad wolf. It’s your dad. Your dad just forgot. Why don’t you tell me a story? Or do you want to go watch your daddy shave?”

Catherine’s hot water bottle was draped over the tub. Towels were heaped on the floor. Henry’s things had been put away behind the mirror. It made him feel tired, thinking of all the other things that still had to be put away. He washed his hands, then looked at the bar of soap. It didn’t feel right. He put it back on the sink, bent over and sniffed it and then tore off a piece of toilet paper, used the toilet paper to pick up the soap. He threw it in the trash and unwrapped a new bar of soap. There was nothing wrong with the new soap. There was nothing wrong with the old soap either. He was just tired. He washed his hands and lathered up his face, shaved off his beard and watched the little bristles of hair wash down the sink. When he went to show Carleton his brand-new face, Catherine was curled up in bed beside Carleton. They were both asleep. They were still asleep when he left the house at 5:30 the next morning.

“Where are you?” Catherine said.

“I’m on my way home. I’m on the train.” The train was still in the station. They would be leaving any minute. They had been leaving any minute for the last hour or so, and before that, they had had to get off the train twice, and then back on again. They had been assured there was nothing to worry about. There was no bomb threat. There was no bomb. The delay was only temporary. The people on the train looked at each other, trying to seem as if they were not looking. Everyone had their cell phones out.

“The rabbits are out on the lawn again,” Catherine said. “There must be at least fifty or sixty. I’ve never counted rabbits before. Tilly keeps trying to go outside to make friends with them, but as soon as she’s outside, they all go bouncing away like beach balls. I talked to a lawn specialist today. He says we need to do something about it, which is what Liz was saying. Rabbits can be a big problem out here. They’ve probably got tunnels and warrens all through the yard. It could be a problem. Like living on top of a sinkhole. But Tilly is never going to forgive us. She knows something’s up. She says she doesn’t want a dog anymore. It would scare away the rabbits. Do you think we should get a dog?”

“So what do they do? Put out poison? Dig up the yard?” Henry said. The man in the seat in front of him got up. He took his bags out of the luggage rack and left the train. Everyone watched him go, pretending they were not.

“He was telling me they have these devices, kind of like ultrasound equipment. They plot out the tunnels, close them up, and then gas the rabbits. It sounds gruesome,” Catherine said. “And this kid, this baby has been kicking the daylights out of me. All day long it’s kick, kick, jump, kick, like some kind of martial artist. He’s going to be an angry kid, Henry. Just like his sister. Her sister. Or maybe I’m going to give birth to rabbits.”

“As long as they have your eyes and my chin,” Henry said.

“I’ve gotta go,” Catherine said. “I have to pee again. All day long it’s the kid jumping, me peeing, Tilly getting her heart broken because she can’t make friends with the rabbits, me worrying because she doesn’t want to make friends with other kids, just with rabbits, Carleton asking if today he has to go to school, does he have to go to school tomorrow, why am I making him go to school when everybody there is bigger than him, why is my stomach so big and fat, why does his teacher tell him to act like a big boy? Henry, why are we doing this again? Why am I pregnant? And where are you? Why aren’t you here? What about our deal? Don’t you want to be here?”

“I’m sorry,” Henry said. “I’ll talk to The Crocodile. We’ll work something out.”

“I thought you wanted this too, Henry. Don’t you?”

“Of course,” Henry said. “Of course I want this.”

“I’ve gotta go,” Catherine said again. “Liz is bringing some women over. We’re finally starting that book club. We’re going to read Fight Club. Her stepdaughter Alison is going to look after Tilly and Carleton for me. I’ve already talked to Tilly. She promises she won’t bite or hit or make Alison cry.”

“What’s the trade? A few hours of bonus TV?”

“No,” Catherine said. “Something’s up with the TV.”

“What’s wrong with the TV?”

“I don’t know,” Catherine said. “It’s working fine. But the kids won’t go near it. Isn’t that great? It’s the same thing as the toothbrush. You’ll see when you get home. I mean, it’s not just the kids. I was watching the news earlier, and then I had to turn it off. It wasn’t the news. It was the TV.”

“So it’s the downstairs bathroom and the coffeemaker and Carleton’s toothbrush and now the TV?”

“There’s some other stuff as well, since this morning. Your office, apparently. Everything in it — your desk, your bookshelves, your chair, even the paper clips.”

“That’s probably a good thing, right? I mean, that way they’ll stay out of there.”

“I guess,” Catherine said. “The thing is, I went and stood in there for a while and it gave me the creeps too. So now I can’t pick up email. And I had to throw out more soap. And King Spanky doesn’t love the alarm clock anymore. He won’t come out from under the bed when I set it off.”

“The alarm clock too?”

“It does sound different,” Catherine said. “Just a little bit different. Or maybe I’m insane. This morning, Carleton told me that he knew where our house was. He said we were living in a secret part of Central Park. He said he recognizes the trees. He thinks that if he walks down that little path, he’ll get mugged. I’ve really got to go, Henry, or I’m going to wet my pants, and I don’t have time to change again before everyone gets here.”

“I love you,” Henry said.

“Then why aren’t you here?” Catherine said victoriously. She hung up and ran down the hallway towards the downstairs bathroom. But when she got there, she turned around. She went racing up the stairs, pulling down her pants as she went, and barely got to the master bedroom bathroom in time. All day long she’d gone up and down the stairs, feeling extremely silly. There was nothing wrong with the downstairs bathroom. It’s just the fixtures. When you flush the toilet or run water in the sink. She doesn’t like the sound the water makes.

Several times now, Henry had come home and found Catherine painting rooms, which was a problem. The problem was that Henry kept going away. If he didn’t keep going away, he wouldn’t have to keep coming home. That was Catherine’s point. Henry’s point was that Catherine wasn’t supposed to be painting rooms while she was pregnant. Pregnant women weren’t supposed to breathe around paint fumes.

Catherine solved this problem by wearing the gas mask while she painted. She had known the gas mask would come in handy. She told Henry she promised to stop painting as soon as he started working at home, which was the plan. Meanwhile, she couldn’t decide on colors. She and Carleton and Tilly spent hours looking at paint strips with colors that had names like Sangria, Peat Bog, Tulip, Tantrum, Planetarium, Galactica, Tea Leaf, Egg Yolk, Tinker Toy, Gauguin, Susan, Envy, Aztec, Utopia, Wax Apple, Rice Bowl, Cry Baby, Fat Lip, Green Banana, Trampoline, Finger Nail. It was a wonderful way to spend time. They went off to school, and when they got home, the living room would be Harp Seal instead of Full Moon. They’d spend some time with that color, getting to know it, ignoring the television, which was haunted (haunted wasn’t the right word, of course, but Catherine couldn’t think what the right word was), and then a couple of days later, Catherine would go buy some more primer and start again. Carleton and Tilly loved this. They begged her to repaint their bedrooms. She did.

She wished she could eat paint. Whenever she opened a can of paint, her mouth watered. When she’d been pregnant with Carleton, she hadn’t been able to eat anything except for olives and hearts of palm and dry toast. When she’d been pregnant with Tilly, she’d eaten dirt, once, in Central Park. Tilly thought they should name the baby after a paint color, Chalk, or Dilly Dilly, or Keelhauled. Lapis Lazulily. Knock Knock.

Catherine kept meaning to ask Henry to take the television and put it in the garage. Nobody ever watched it now. They’d had to stop using the microwave as well, and a colander, some of the flatware, and she was keeping an eye on the toaster. She had a premonition, or an intuition. It didn’t feel wrong, not yet, but she had a feeling about it. There was a gorgeous pair of earrings that Henry had given her — how was it possible to be spooked by a pair of diamond earrings? — and yet. Carleton wouldn’t play with his Lincoln Logs, and so they were going to the Salvation Army, and Tilly’s armadillo purse had disappeared. Tilly hadn’t said anything about it, and Catherine hadn’t wanted to ask.

Sometimes, if Henry wasn’t coming home, Catherine painted after Carleton and Tilly went to bed. Sometimes Tilly would walk into the room where Catherine was working, Tilly’s eyes closed, her mouth open, a tourist-somnambulist. She’d stand there, with her head cocked towards Catherine. If Catherine spoke to her, she never answered, and if Catherine took her hand, she would follow Catherine back to her own bed and lie down again. But sometimes Catherine let Tilly stand there and keep her company. Tilly was never so attentive, so present, when she was awake. Eventually she would turn and leave the room and Catherine would listen to her climb back up the stairs. Then she would be alone again.

Catherine dreams about colors. It turns out her marriage was the same color she had just painted the foyer. Velveteen Fade. Leonard Felter, who had had an ongoing affair with two of his graduate students, several adjuncts, two tenured faculty members, brought down Catherine’s entire department, and saved Catherine’s marriage, would make a good lipstick or nail polish. Peach Nooky. There’s The Crocodile, a particularly bilious Eau De Vil, a color that tastes bad when you say it. Her mother, who had always been disappointed by Catherine’s choices, turned out to have been a beautiful, rich, deep chocolate. Why hadn’t Catherine ever seen that before? Too late, too late. It made her want to cry.

Liz and she are drinking paint. “Have some more paint,” Catherine says. “Do you want sugar?”

“Yes, lots,” Liz says. “What color are you going to paint the rabbits?”

Catherine passes her the sugar. She hasn’t even thought about the rabbits, except which rabbits does Liz mean, the stone rabbits or the real rabbits? How do you make them hold still?

“I got something for you,” Liz says. She’s got Tilly’s armadillo purse. It’s full of paint strips. Catherine’s mouth fills with saliva.

Henry dreams he has an appointment with the exterminator. “You’ve got to take care of this,” he says. “We have two small children. These things could be rabid. They might carry plague.”

“See what I can do,” the exterminator says, sounding glum. He stands next to Henry. He’s an odd-looking, twitchy guy. He has big ears. They contemplate the skyscrapers that poke out of the grass like obelisks. The lawn is teeming with skyscrapers. “Never seen anything like this before. Never wanted to see anything like this. But if you want my opinion, it’s the house that’s the real problem — ”

“Never mind about my wife,” Henry says. He squats down beside a knee-high art-deco skyscraper, and peers into a window. A little man looks back at him and shakes his fists, screaming something obscene. Henry flicks a finger at the window, almost hard enough to break it. He feels hot all over. He’s never felt this angry before in his life, not even when Catherine told him that she’d accidentally slept with Leonard Felter. The little bastard is going to regret what he just said, whatever it was. He lifts his foot.

The exterminator says, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you. You have to dig them up, get the roots. Otherwise, they just grow back. Like your house. Which is really just the tip of the iceberg lettuce, so to speak. You’ve probably got seventy, eighty stories underground. You gone down on the elevator yet? Talked to the people living down there? It’s your house, and you’re just going to let them live there rent-free? Mess with your things like that?”

“What?” Henry says, and then he hears helicopters, fighter planes the size of hummingbirds. “Is this really necessary?” he says to the exterminator.

The exterminator nods. “You have to catch them off guard.”

“Maybe we’re being hasty,” Henry says. He has to yell to be heard above the noise of the tiny, tinny, furious planes. “Maybe we can settle this peacefully.”

“Hemree,” the interrogator says, shaking his head. “You called me in, because I’m the expert, and you knew you needed help.”

Henry wants to say “You’re saying my name wrong.” But he doesn’t want to hurt the undertaker’s feelings.

The alligator keeps on talking. “Listen up, Hemreeee, and shut up about negotiations and such, because if we don’t take care of this right away, it may be too late. This isn’t about homeownership, or lawn care, Hemreeeeee, this is war. The lives of your children are at stake. The happiness of your family. Be brave. Be strong. Just hang on to your rabbit and fire when you see delight in their eyes.”

He woke up. “Catherine,” he whispered. “Are you awake? I was having this dream.”

Catherine laughed. “That’s the phone, Liz,” she said. “It’s probably Henry, saying he’ll be late.”

“Catherine,” Henry said. “Who are you talking to?”

“Are you mad at me, Henry?” Catherine said. “Is that why you won’t come home?”

“I’m right here,” Henry said.

“You take your rabbits and your crocodiles and get out of here,” Catherine said. “And then come straight home again.”

She sat up in bed and pointed her finger. “I am sick and tired of being spied on by rabbits!”

When Henry looked, something stood beside the bed, rocking back and forth on its heels. He fumbled for the light, got it on, and saw Tilly, her mouth open, her eyes closed. She looked larger than she ever did when she was awake. “It’s just Tilly,” he said to Catherine, but Catherine lay back down again. She put her pillow over her head. When he picked Tilly up, to carry her back to bed, she was warm and sweaty, her heart racing as if she had been running through all the rooms of the house.

He walked through the house. He rapped on walls, testing. He put his ear against the floor. No elevator. No secret rooms, no hidden passageways.

There isn’t even a basement.

Tilly has divided the yard in half. Carleton is not allowed in her half, unless she gives permission.

From the bottom of her half of the yard, where the trees run beside the driveway, Tilly can barely see the house. She’s decided to name the yard Matilda’s Rabbit Kingdom. Tilly loves naming things. When the new baby is born, her mother has promised that she can help pick out the real names, although there will only be two real names, a first one and a middle. Tilly doesn’t understand why there can only be two. Oishi means “delicious” in Japanese. That would make a good name, either for the baby or for the yard, because of the grass. She knows the yard isn’t as big as Central Park, but it’s just as good, even if there aren’t any pagodas or castles or carriages or people on roller skates. There’s plenty of grass. There are hundreds of rabbits. They live in an enormous underground city, maybe a city just like New York. Maybe her dad can stop working in New York, and come work under the lawn instead. She could help him, go to work with him. She could be a biologist, like Jane Goodall, and go and live underground with the rabbits. Last year her ambition had been to go and live secretly in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but someone has already done that, even if it’s only in a book. Tilly feels sorry for Carleton. Everything he ever does, she’ll have already been there. She’ll already have done that.

Tilly has left her armadillo purse sticking out of a rabbit hole. First she made the hole bigger; then she packed the dirt back in around the armadillo so that only the shiny, peeled snout poked out. Carleton digs it out again with his stick. Maybe Tilly meant him to find it. Maybe it was a present for the rabbits, except what is it doing here, in his half of the yard? When he lived in the apartment, he was afraid of the armadillo purse, but there are better things to be afraid of out here. But be careful, Carleton. Might as well be careful. The armadillo purse says Don’t touch me. So he doesn’t. He uses his stick to pry open the snapmouth, dumps out Tilly’s most valuable things, and with his stick pushes them one by one down the hole. Then he puts his ear to the rabbit hole so that he can hear the rabbits say thank you. Saying thank you is polite. But the rabbits say nothing. They’re holding their breath, waiting for him to go away. Carleton waits too. Tilly’s armadillo, empty and smelly and haunted, makes his eyes water.

Someone comes up and stands behind him. “I didn’t do it,” he says. “They fell.”

But when he turns around, it’s the girl who lives next door. Alison. The sun is behind her and makes her shine. He squints.

“You can come over to my house if you want to,” she says. “Your mom says. She’s going to pay me fifteen bucks an hour, which is way too much. Are your parents really rich or something? What’s that?”

“It’s Tilly’s,” he says. “But I don’t think she wants it anymore.”

She picks up Tilly’s armadillo. “Pretty cool,” she says. “Maybe I’ll keep it for her.”

Deep underground, the rabbits stamp their feet in rage.

Catherine loves the house. She loves her new life. She’s never understood people who get stuck, become unhappy, can’t change, can’t adapt. So she’s out of a job. So what? She’ll find something else to do. So Henry can’t leave his job yet, won’t leave his job yet. So the house is haunted. That’s okay. They’ll work through it. She buys some books on gardening. She plants a rosebush and a climbing vine in a pot. Tilly helps. The rabbits eat off all the leaves. They bite through the vine.

“Shit,” Catherine says when she sees what they’ve done. She shakes her fists at the rabbits on the lawn. The rabbits flick their ears at her. They’re laughing, she knows it. She’s too big to chase after them.

“Henry, wake up. Wake up.”

“I’m awake,” he said, and then he was. Catherine was crying: noisy, wet, ugly sobs. He put his hand out and touched her face. Her nose was running.

“Stop crying,” he said. “I’m awake. Why are you crying?”

“Because you weren’t here,” she said. “And then I woke up and you were here, but when I wake up tomorrow morning you’ll be gone again. I miss you. Don’t you miss me?”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m sorry I’m not here. I’m here now. Come here.”

“No,” she said. She stopped crying, but her nose still leaked. “And now the dishwasher is haunted. We have to get a new dishwasher before I have this baby. You can’t have a baby and not have a dishwasher. And you have to live here with us. Because I’m going to need some help this time. Remember Carleton, how fucking hard that was.”

“He was one cranky baby,” Henry said.

When Carleton was three months old, Henry had realized that they’d misunderstood something. Babies weren’t babies — they were land mines; bear traps; wasp nests. They were a noise, which was sometimes even not a noise, but merely a listening for a noise; they were a damp, chalky smell; they were the heaving, jerky, sticky manifestation of not-sleep. Once Henry had stood and watched Carleton in his crib, sleeping peacefully. He had not done what he wanted to do. He had not bent over and yelled in Carleton’s ear. Henry still hadn’t forgiven Carleton, not yet, not entirely, not for making him feel that way.

“Why do you have to love your job so much?” Catherine said.

“I don’t know,” Henry said. “I don’t love it.”

“Don’t lie to me,” Catherine said.

“I love you better,” Henry said. He does, he does, he does love Catherine better. He’s already made that decision. But she isn’t even listening.

“Remember when Carleton was little and you would get up in the morning and go to work and leave me all alone with them?” Catherine poked him in the side. “I used to hate you. You’d come home with takeout, and I’d forget I hated you, but then I’d remember again, and I’d hate you even more because it was so easy for you to trick me, to make things okay again, just because for an hour I could sit in the bathtub and eat Chinese food and wash my hair.”

“You used to carry an extra shirt with you, when you went out,” Henry said. He put his hand down inside her T-shirt, on her fat, full breast. “In case you leaked.”

“You can’t touch that breast,” Catherine said. “It’s haunted.” She blew her nose on the sheets.

Catherine’s friend Lucy owns an online boutique, Nice Clothes for Fat People. There’s a woman in Tarrytown who knits stretchy, sexy Argyle sweaters exclusively for NCFP, and Lucy has an appointment with her. She wants to stop off and see Catherine afterwards, before she has to drive back to the city again. Catherine gives her directions, and then begins to clean house, feeling out of sorts. She’s not sure she wants to see Lucy right now. Carleton has always been afraid of Lucy, which is embarrassing. And Catherine doesn’t want to talk about Henry. She doesn’t want to explain about the downstairs bathroom. She had planned to spend the day painting the wood trim in the dining room, but now she’ll have to wait.

The doorbell rings, but when Catherine goes to answer it, no one is there. Later on, after Tilly and Carleton have come home, it rings again, but no one is there. It rings and rings, as if Lucy is standing outside, pressing the bell over and over again. Finally Catherine pulls out the wire. She tries calling Lucy’s cell phone, but can’t get through. Then Henry calls. He says that he’s

going to be late.

Liz opens the front door, yells, “Hello, anyone home! You’ve got to see your rabbits, there must be thousands of them. Catherine, is something wrong with your doorbell?”

Henry’s bike, so far, was okay. He wondered what they’d do if the Toyota suddenly became haunted. Would Catherine want to sell it? Would resale value be affected? The car and Catherine and the kids were gone when he got home, so he put on a pair of work gloves and went through the house with a cardboard box, collecting all the things that felt haunted. A hairbrush in Tilly’s room, an old pair of Catherine’s tennis shoes. A pair of Catherine’s underwear that he finds at the foot of the bed. When he picked them up he felt a sudden shock of longing for Catherine, like he’d been hit by some kind of spooky lightning. It hit him in the pit of the stomach, like a cramp. He dropped them in the box.

The silk kimono from Takashimaya. Two of Carleton’s nightlights. He opened the door to his office, put the box inside. All the hair on his arms stood up. He closed the door.

Then he went downstairs and cleaned paintbrushes. If the paintbrushes were becoming haunted, if Catherine was throwing them out and buying new ones, she wasn’t saying. Maybe he should check the Visa bill. How much were they spending on paint, anyway?

Catherine came into the kitchen and gave him a hug. “I’m glad you’re home,” she said. He pressed his nose into her neck and inhaled. “I left the car running — I’ve got to pee. Would you go pick up the kids for me?”

“Where are they?” Henry said.

“They’re over at Liz’s. Alison is babysitting them. Do you have money on you?”

“You mean I’ll meet some neighbors?”

“Wow, sure,” Catherine said. “If you think you’re ready. Are you ready? Do you know where they live?”

“They’re our neighbors, right?”

“Take a left out of the driveway, go about a quarter of a mile, and they’re the red house with all the trees in front.”

But when he drove up to the red house and went and rang the doorbell, no one answered. He heard a child come running down a flight of stairs and then stop and stand in front of the door. “Carleton? Alison?” he said. “Excuse me, this is Catherine’s husband, Henry. Carleton and Tilly’s dad.” The whispering stopped. He waited for a bit. When he crouched down and lifted the mail slot, he thought he saw someone’s feet, the hem of a coat, something furry? A dog? Someone standing very still, just to the right of the door? Carleton, playing games. “I see you,” he said, and wiggled his fingers through the mail slot. Then he thought maybe it wasn’t Carleton after all. He got up quickly and went back to the car. He drove into town and bought more soap.

Tilly was standing in the driveway when he got home, her hands on her hips. “Hi, Dad,” she said. “I’m looking for King Spanky. He got outside. Look what Alison found.”

She held out a tiny toy bow strung with what looked like dental floss, an arrow as small as a needle.

“Be careful with that,” Henry said. “It looks sharp. Archery Barbie, right? So did you guys have a good time with Alison?”

“Alison’s okay,” Tilly said. She belched. “’Scuse me. I don’t feel very good.”

“What’s wrong?” Henry said.

“My stomach is funny,” Tilly said. She looked up at him, frowned, and then vomited all over his shirt, his pants.

“Tilly!” he said. He yanked off his shirt, used a sleeve to wipe her mouth. The vomit was foamy and green.

“It tastes horrible,” she said. She sounded surprised. “Why does it always taste so bad when you throw up?”

“So that you won’t go around doing it for fun,” he said. “Are you going to do it again?”

“I don’t think so,” she said, making a face.

“Then I’m going to go wash up and change clothes. What were you eating, anyway?”

“Grass,” Tilly said.

“Well, no wonder,” Henry said. “I thought you were smarter than that, Tilly. Don’t do that anymore.”

“I wasn’t planning to,” Tilly said. She spat in the grass.

When Henry opened the front door, he could hear Catherine talking in the kitchen. “The funny thing is,” she said, “none of it was true. It was just made up, just like something Carleton would do. Just to get attention.”

“Dad,” Carleton said. He was jumping up and down on one foot. “Want to hear a song?”

“I was looking for you,” Henry said. “Did Alison bring you home? Do you need to go to the bathroom?”

“Why aren’t you wearing any clothes?” Carleton said.

Someone in the kitchen laughed, as if they had heard this.

“I had an accident,” Henry said, whispering. “But you’re right, Carleton, I should go change.” He took a shower, rinsed and wrung out his shirt, put on clean clothes, but by the time he got downstairs, Catherine and Carleton and Tilly were eating Cheerios for dinner. They were using paper bowls, plastic spoons, as if it were a picnic. “Liz was here, and Alison, but they were going to a movie,” she said. “They said they’d meet you some other day. It was awful — when they came in the door, King Spanky went rushing outside. He’s been watching the rabbits all day. If he catches one, Tilly is going to be so upset.”

“Tilly’s been eating grass,” Henry said.

Tilly rolled her eyes. As if.

“Not again!” Catherine said. “Tilly, real people don’t eat grass. Oh, look, fantastic, there’s King Spanky. Who let him in? What’s he got in his mouth?”

King Spanky sits with his back to them. He coughs and something drops to the floor, maybe a frog, or a baby rabbit. It goes scrabbling across the floor, half-leaping, dragging one leg. King Spanky just sits there, watching as it disappears under the sofa. Carleton freaks out. Tilly is shouting “Bad King Spanky! Bad cat!” When Henry and Catherine push the sofa back, it’s too late, there’s just King Spanky and a little blob of sticky blood on the floor.

Catherine would like to write a novel. She’d like to write a novel with no children in it. The problem with novels with children in them is that bad things will happen either to the children or else to the parents. She wants to write something funny, something romantic.

It isn’t very comfortable to sit down now that she’s so big. She’s started writing on the walls. She writes in pencil. She names her characters after paint colors. She imagines them leading beautiful, happy, useful lives. No haunted toasters. No mothers no children no crocodiles no photocopy machines no Leonard Felters. She writes for two or three hours, and then she paints the walls again before anyone gets home. That’s always the best part.

“I need you next weekend,” The Crocodile said. Her rubber band ball sat on the floor beside her desk. She had her feet up on it, in an attempt to show it who was boss. The rubber band ball was getting too big for its britches. Someone was going to have to teach it a lesson, send it a memo.

She looked tired. Henry said, “You don’t need me.”

“I do,” The Crocodile said, yawning. “I do. The clients want to take you out to dinner at Four Seasons when they come in to town. They want to go see musicals with you. Rent. Phantom of the Cabaret Lion. They want to go to Coney Island with you and eat hot dogs. They want to go out to trendy bars and clubs and pick up strippers and publicists and performance artists. They want to talk about poetry, philosophy, sports, politics, their lousy relationships with their fathers. They want to ask you for advice about their love lives. They want you to come to the weddings of their children and make toasts. You’re indispensable, honey. I hope you know that.”

“Catherine and I are having some problems with rabbits,” Henry said. The rabbits were easier to explain than the other thing. “They’ve taken over the yard. Things are a little crazy.”

“I don’t know anything about rabbits,” The Crocodile said, digging her pointy heels into the flesh of the rubber band ball until she could feel the red rubber blood come running out. She pinned Henry with her beautiful, watery eyes.

“Henry.” She said his name so gently that he had to lean forward to hear what she was saying.

She said, “You have the best of both worlds. A wife and children who adore you, a beautiful house in the country, a secure job at a company that depends on you, a boss who appreciates your talents, clients who think you’re the shit. You are the shit, Henry, and the thing is, you’re probably thinking that no one deserves to have all this. You think you have to make a choice. You think you have to give up something. But you don’t have to give up anything, Henry, and anyone who tells you otherwise is a fucking rabbit. Don’t listen to them. You can have it all. You deserve to have it all. You love your job. Do you love your job?”

“I love my job,” Henry says. The Crocodile smiles at him tearily.

It’s true. He loves his job.

When Henry came home, it must have been after midnight, because he never got home before midnight. He found Catherine standing on a ladder in the kitchen, one foot resting on the sink. She was wearing her gas mask, a black cotton sports bra, and a pair of black sweatpants rolled down so he could see she wasn’t wearing any underwear. Her stomach stuck out so far, she had to hold her arms at a funny angle to run the roller up and down the wall in front of her. Up and down in a V. Then fill the V in. She had painted the kitchen ceiling a shade of purple so dark, it almost looked black. Midnight Eggplant.

Catherine has been buying paints from a specialty catalog. All the colors are named after famous books, Madame Bovary, Forever Amber, Fahrenheit 451, The Tin Drum, A Curtain of Green, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. She was painting the walls Catch-22, a novel she’d taught over and over again to undergraduates. It always went over well. The paint color was nice too. She couldn’t decide if she missed teaching. The thing about teaching and having children is that you always ended up treating your children like undergraduates, and your undergraduates like children. There was a particular tone of voice. She’d even used it on Henry a few times, just to see if it worked.

All the cabinets were fenced around with masking tape, like a crime scene. The room stank of new paint.

Catherine took off the gas mask and said, “Tilly picked it out. What do you think?” Her hands were on her hips. Her stomach poked out at Henry. The gas mask had left a ring of white and red around her eyes and chin.

Henry said, “How was the dinner party?”

“We had fettuccine. Liz and Marcus stayed and helped me do the dishes.”

(“Is something wrong with your dishwasher?” “No. I mean, yes. We’re getting a new one.”)

She had had a feeling. It had been a feeling like déjà vu, or being drunk, or falling in love. Like teaching. She had imagined an audience of rabbits out on the lawn, watching her dinner party. A classroom of rabbits, watching a documentary. Rabbit television. Her skin had felt electric.

“So she’s a lawyer?” Henry said.

“You haven’t even met them yet,” Catherine said, suddenly feeling possessive. “But I like them. I really, really like them. They wanted to know all about us. You. I think they think that either we’re having marriage problems or that you’re imaginary. Finally I took Liz upstairs and showed her your stuff in the closet. I pulled out the wedding album and showed them photos.”

“Maybe we could invite them over on Sunday? For a cookout?” Henry said.

“They’re away next weekend,” Catherine said. “They’re going up to the mountains on Friday. They have a house up there. They’ve invited us. To come along.”

“I can’t,” Henry said. “I have to take care of some clients next weekend. Some big shots. We’re having some cash flow problems. Besides, are you allowed to go away? Did you check with your doctor, what’s his name again, Dr. Marks?”

“You mean, did I get my permission slip signed?” Catherine said. Henry put his hand on her leg and held on. “Dr. Marks said I’m shipshape. Those were his exact words. Or maybe he said tip-top. It was something alliterative.”

“Well, I guess you ought to go, then,” Henry said. He rested his head against her stomach. She let him. He looked so tired. “Before Golf Cart shows up. Or what is Tilly calling the baby now?”

“She’s around here somewhere,” Catherine said. “I keep putting her back in her bed and she keeps getting out again. Maybe she’s looking for you.”

“Did you get my email?” Henry said. He was listening to Catherine’s stomach. He wasn’t going to stop touching her unless she told him to.

“You know I can’t check email on your computer anymore,” Catherine said.

“This is so stupid,” Henry said. “This house isn’t haunted. There isn’t any such thing as a haunted house.”

“It isn’t the house,” Catherine said. “It’s the stuff we brought with us. Except for the downstairs bathroom, and that might just be a draft, or an electrical problem. The house is fine. I love the house.”

“Our stuff is fine,” Henry said. “I love our stuff.”

“If you really think our stuff is fine,” Catherine said, “then why did you buy a new alarm clock? Why do you keep throwing out the soap?”

“It’s the move,” Henry said. “It was a hard move.”

“King Spanky hasn’t eaten his food in three days,” Catherine said. “At first I thought it was the food, and I bought new food and he came down and ate it and I realized it wasn’t the food, it was King Spanky. I couldn’t sleep all night, knowing he was up under the bed. Poor spooky guy. I don’t know what to do. Take him to the vet? What do I say? Excuse me, but I think my cat is haunted? Anyway, I can’t get him out of the bed. Not even with the old alarm clock, the haunted one.”

“I’ll try,” Henry said. “Let me try and see if I can get him out.” But he didn’t move. Catherine tugged at a piece of his hair and he put up his hand. She gave him her roller. He popped off the cylinder and bagged it and put it in the freezer, which was full of paintbrushes and other rollers. He helped Catherine down from the ladder. “I wish you would stop painting.”

“I can’t,” she said. “It has to be perfect. If I can just get it right, then everything will go back to normal and stop being haunted and the rabbits won’t tunnel under the house and make it fall down, and you’ll come home and stay home, and our neighbors will finally get to meet you and they’ll like you and you’ll like them, and Carleton will stop being afraid of everything, and Tilly will fall asleep in her own bed, and stay there, and — ”

“Hey,” Henry said. “It’s all going to work out. It’s all good. I really like this color.”

“I don’t know,” Catherine said. She yawned. “You don’t think it looks too old-fashioned?”

They went upstairs and Catherine took a bath while Henry tried to coax King Spanky out of the bed. But King Spanky wouldn’t come out. When Henry got down on his hands and knees, and stuck the flashlight under the bed, he could see King Spanky’s eyes, his tail hanging down from the box frame.

Out on the lawn the rabbits were perfectly still. Then they sprang up in the air, turning and dropping and landing and then freezing again. Catherine stood at the window of the bathroom, toweling her hair. She turned the bathroom light off, so that she could see them better. The moonlight picked out their shining eyes, the moon-colored fur, each hair tipped in paint. They were playing some rabbit game like leapfrog. Or they were dancing the quadrille. Fighting a rabbit war. Did rabbits fight wars? Catherine didn’t know. They ran at each other and then turned and darted back, jumping and crouching and rising up on their back legs. A pair of rabbits took off like racehorses, sailing through the air and over a long curled shape in the grass. Then back over again. She put her face against the window. It was Tilly, stretched out against the grass, Tilly’s legs and feet bare and white.

“Tilly,” she said, and ran out of the bathroom, wearing only the towel around her hair.

“What is it?” Henry said as Catherine darted past him, and down the stairs. He ran after her, and by the time she had opened the front door, was kneeling beside Tilly, the wet grass tickling her thighs and her belly, Henry was there too, and he picked up Tilly and was carrying her back into the house. They wrapped her in a blanket and put her in her bed, and because neither of them wanted to sleep in the bed where King Spanky was hiding, they lay down on the sofa in the family room, curled up against each other. When they woke up in the morning, Tilly was asleep in a ball at their feet.

For a whole minute or two, last year, Catherine thought she had it figured out. She was married to a man whose specialty was solving problems, salvaging bad situations. If she did something dramatic enough, if she fucked up badly enough, it would save her marriage. And it did, except that once the problem was solved and the marriage was saved and the baby was conceived and the house was bought, then Henry went back to work.

She stands at the window in the bedroom and looks out at all the trees. For a minute she imagines that Carleton is right, and they are living in Central Park and Fifth Avenue is just right over there. Henry’s office is just a few blocks away. All those rabbits are just tourists.

Henry wakes up in the middle of the night. There are people downstairs. He can hear women talking, laughing, and he realizes Catherine’s book club must have come over. He gets out of bed. It’s dark. What time is it anyway? But the alarm clock is haunted again. He unplugs it. As he comes down the stairs, a voice says, “Well, will you look at that!” and then, “Right under his nose the whole time!”

Henry walks through the house, turning on lights. Tilly stands in the middle of the kitchen. “May I ask who’s calling?” she says. She’s got Henry’s cell phone tucked between her shoulder and her face. She’s holding it upside down. Her eyes are open, but she’s asleep.

“Who are you talking to?” Henry says.

“The rabbits,” Tilly says. She tilts her head, listening. Then she laughs. “Call back later,” she says. “He doesn’t want to talk to you. Yeah. Okay.” She hands Henry his phone. “They said it’s no one you know.”

“Are you awake?” Henry says.

“Yes,” Tilly says, still asleep. He carries her back upstairs. He makes a bed out of pillows in the hall closet and lays her down across them. He tucks a blanket around her. If she refuses to wake up in the same bed that she goes to sleep in, then maybe they should make it a game. If you can’t beat them, join them.

Catherine hadn’t had an affair with Leonard Felter. She hadn’t even slept with him. She had just said she had, because she was so mad at Henry. She could have slept with Leonard Felter. The opportunity had been there. And he had been magical, somehow: the only member of the department who could make the photocopier make copies, and he was nice to all of the secretaries. Too nice, as it turned out. And then, when it turned out that Leonard Felter had been fucking everyone, Catherine had felt she couldn’t take it back. So she and Henry had gone to therapy together. Henry had taken some time off work. They’d taken the kids to Yosemite. They’d gotten pregnant. She’d been remorseful for something she hadn’t done. Henry had forgiven her. Really, she’d saved their marriage. But it had been the sort of thing you could do only once.

If someone has to save the marriage a second time, it will have to be Henry.

Henry went looking for King Spanky. They were going to see the vet: he had the cat cage in the car, but no King Spanky. It was early afternoon, and the rabbits were out on the lawn. Up above, a bird hung, motionless, on a hook of air. Henry craned his head, looking up. It was a big bird, a hawk maybe. It circled, once, twice, again, and then dropped like a stone, towards the rabbits. The rabbits didn’t move. There was something about the way they waited, as if this were all a game. The bird dropped through the air, folded like a knife, and then it jerked, tumbled, fell. The wings loose. The bird smashed into the grass and feathers flew up. The rabbits moved closer, as if investigating.

Henry went to see for himself. The rabbits scattered, and the lawn was empty. No rabbits, no bird. But there, down in the trees, beside the bike path, Henry saw something move. King Spanky swung his tail angrily, slunk into the woods.

When Henry came out of the woods, the rabbits were back, guarding the lawn again, and Catherine was calling his name.

“Where were you?” she said. She was wearing her gas mask around her neck, and there was a smear of paint on her arm. Whiskey Horse. She’d been painting the linen closet.

“King Spanky took off,” Henry said. “I couldn’t catch him. I saw the weirdest thing — this bird was going after the rabbits, and then it fell — ”

“Marcus came by,” Catherine said. Her cheeks were flushed. He knew that if he touched her, her skin would be hot. “He stopped by to see if you wanted to go play golf.”

“Who wants to play golf?” Henry said. “I want to go upstairs with you. Where are the kids?”

“Alison took them into town, to see a movie,” Catherine said. “I’m going to pick them up at three.”

Henry lifted the gas mask off her neck, fitted it around her face. He unbuttoned her shirt, undid the clasp of her bra. “Better take this off,” he said. “Better take all your clothes off. I think they’re haunted.”

“You know what would make a great paint color? Can’t believe no one has done this yet. Yellow Sticky. What about King Spanky?” Catherine said. She sounded like Darth Vader, maybe on purpose, and Henry thought it was sexy: Darth Vader, pregnant, with his child. She put her hand against his chest and shoved. Not too hard, but harder than she meant to. It turned out that painting had given her some serious muscle. That will be a good thing when she has another kid to haul around.

“Yellow Sticky. That’s great. Forget King Spanky,” Henry said. “King Spanky is a terrible name for a paint color.”

Catherine was painting Tilly’s room Lavender Fist. It was going to be a surprise. But when Tilly saw it, she burst into tears. “Why can’t you just leave it alone?” she said. “I liked it the way it was.”

“I thought you liked purple,” Catherine said, astounded. She took off her gas mask.

“I hate purple,” Tilly said. “And I hate you. You’re so fat. Even Carleton thinks so.”

“Tilly!” Catherine said. She laughed. “I’m pregnant, remember?”

“That’s what you think,” Tilly said. She ran out of the room and across the hall. There were crashing noises, the sounds of things breaking.

“Tilly!” Catherine said.

Tilly stood in the middle of Carleton’s room. All around her lay broken night-lights, lamps, broken lightbulbs. The carpet was dusted in glass. Tilly’s feet were bare and Catherine looked down, realized that she wasn’t wearing shoes either. “Don’t move, Tilly,” she said.

“They were haunted,” Tilly said, and began to cry.

“So how come your dad’s never home?” Alison said.

“I don’t know,” Carleton said. “Guess what? Tilly broke all my night-lights.”

“Yeah,” Alison said. “You must be pretty mad.”

“No, it’s good that she did,” Carleton said, explaining. “They were haunted. Tilly didn’t want me to be afraid.”

“But aren’t you afraid of the dark?” Alison said.

“Tilly said I shouldn’t be,” Carleton said. “She said the rabbits stay awake all night, that they make sure everything is okay, even when it’s dark. Tilly slept outside once, and the rabbits protected her.”

“So you’re going to stay with us this weekend,” Alison said.

“Yes,” Carleton said.

“But your dad isn’t coming,” Alison said.

“No,” Carleton said. “I don’t know.”

“Want to go higher?” Alison said. She pushed the swing and sent him soaring.