interviews

Storytelling Is No Innocent Affair

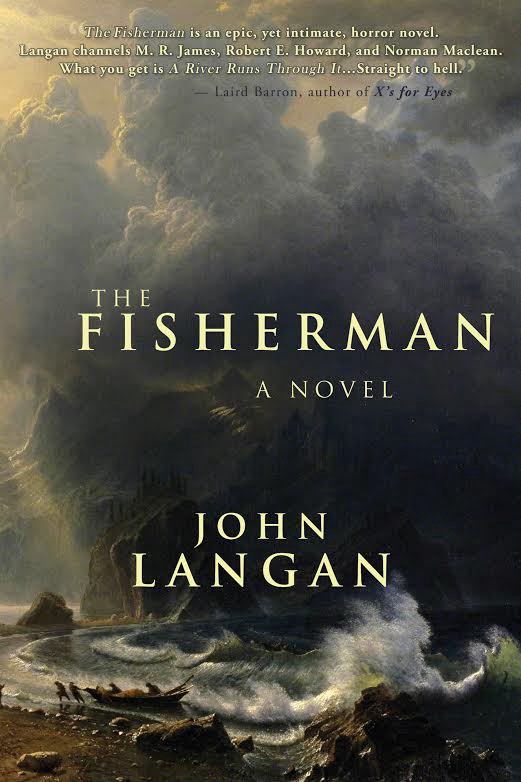

An Interview with John Langan, Author of The Fisherman

My first encounter with John Langan’s fiction came last fall at a reading at Brooklyn’s WORD. There, he read from a novella called “Corpsemouth,” which encompassed everything from a movingly observed depiction of one family’s grieving process to a tale of the uncanny in Arthurian England. I sought out his three books that were out in the world at the time: the novel House of Windows and the collections Mr. Gaunt and Other Uneasy Encounters and The Wide, Carnivorous Sky and Other Monstrous Geographies.

Langan’s fiction often involves stories told within stories, and that’s also true of his new novel The Fisherman (Word Horde, 2016). (It’s one of two books he has due out this year; a collection will follow in the fall.) Set in the Hudson River Valley, it’s about the friendship between two widowers and a trip they make to a mysterious location, and the ominous history that they uncover along the way. There’s a lot to admire in it, from its depictions of grief and loss to the story it tells about the slow economic decline of the region in which it is set, over the course of the last decades of the twentieth century. Oh, and there are monsters, too–some of the most unsettling imagery I’ve encountered in fiction in a long time, and a strain of cosmic horror that takes the style in a memorably different direction. Langan and I conducted this interview via email over several weeks, and touched on everything for the creation of The Fisherman to his feelings on horror to his fondness for nestled narratives.

Tobias Carroll: In your acknowledgements to The Fisherman, you mention that you began work on the novel over a dozen years ago. Was the version as you initially conceived it close to the final version that’s being published, or did it go through several permutations?

John Langan: Oddly enough, given the amount of time between its inception and completion, the novel’s arc is not substantially different from my initial conception of it. From the start, I knew that the book was going to be a kind of weird horror response to Moby Dick; I knew the climax I was writing toward. It was more a case of the novel developing–the word I want to use is “expanding”–as I moved further into it. Which is not to say I didn’t occasionally write myself into blinds; in particular, the climactic confrontation of the book’s story-within-the-story took me a while to arrive at. But the overarching plot structure remained in place.

Carroll: There’s a strong historical component to the novel, including the real-life flooding of several towns in upstate New York to create a reservoir system. When did this piece of history first suggest itself as the backdrop for a longer work of fiction?

Langan: I can’t remember when I first learned about the Ashokan Reservoir; I think I heard some garbled version of its construction when I was an undergraduate. Whoever told me about it claimed that, on a clear day, you could look down into the water and see the top of the steeple of the one of the drowned churches. Even after I visited the actual Reservoir, it was years before I learned that that story was a myth, if a powerful one. That image of the drowned town stuck with me; although I never could seem to find a narrative that was a good fit for it. Then, once I started work on The Fisherman, I knew I’d arrived at the right story for the Reservoir.

Carroll: Much of your work involves storytelling, from the framing device in House of Windows to the tale of Arthurian England told in “Corpsemouth.” As a writer, what appeals to you the most about nestling narratives in this fashion?

Langan: I love stories. In my view, they’re a–even the–fundamental part of what it means to be human. As Salman Rushdie put it, “Man is the Storytelling Animal.” Stories are how we learn the world; how we keep learning it. I come from a family of storytellers: my father was a font of narrative, from funny anecdotes about his time in the British Army to detailed summaries of movies he’d watched; my mother told us stories of her youth, as well as of various family members. I was raised Catholic, and a good deal of my religious instruction came through stories, whether from the Bible or the lives of the saints. I grew up reading the Marvel comics of the sixties and seventies, which were themselves fonts of narrative, and they steered me in the direction of the Greek and Norse myths.

Stories are how we learn the world…

A great deal of the fiction that shaped me as a writer is driven by storytelling: Robert E. Howard’s stories, Stephen King’s fiction, Faulkner’s work. At the same time, as Faulkner and Virginia Woolf made clear to me, storytelling is no innocent affair. I suppose you might call what they taught me the “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” lesson: every story is an illustration of its teller’s perspective. I love the idea of story as something that’s conveying information on multiple levels. I love the idea of different stories within the same work interacting with one another, amplifying meaning, generating new meaning.

Carroll: In The Fisherman, you go even deeper with this idea, with the narrator hearing a story that expands in his mind afterwards. Where did the notion of a nestled narrative of the uncanny that is itself somewhat uncanny come from?

Langan: Actually, that was a late addition to the story. As I originally conceived it, the story within the story was going to be just that, a story, something maybe thirty or forty pages long, of a length that it could be believably recounted within the span of maybe an hour. As the story grew, however, until it was pretty much the same length as the narrative surrounding it, the verisimilitude of it being told in one setting became more of an issue. In my previous novel, House of Windows, I had had a character tell an even longer story over the course of two nights, and despite the example of, say, Joseph Conrad’s work, I received a certain amount of criticism for that choice. I wasn’t concerned too much about the criticism, but I was concerned about anything that might take the reader out of the narrative. I hit on the idea of having the narrative that is included in the novel be a different, fuller version of what my characters originally heard, and highlighting that difference as an instance of the uncanny experience the characters have experienced. While its motivation was rhetorical, I liked the idea of a narrative that was itself supernatural, that had to be told so it could emerge in its fullness, a kind of “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” effect.

Carroll: In the notes on the stories at the end of your collection Mr. Gaunt and Other Uneasy Encounters, you write about the idea of the “trap story,” and how to avoid readers’ expectations. Was there a moment for you when you became determined to avoid cliched aspects when writing horror fiction?

Langan: Pretty much from the beginning–and I mean, back in high school, when I first started writing horror stories–I wanted to avoid those stories where the characters are basically pieces of meat to be sacrificed to the story’s monster figure. It’s one of the temptations of the horror field, this kind of sinister O. Henry form. The problem is, unless you’re a Poe-level genius, these stories tend to be little more than anecdotes, one-note jokes. I wasn’t interested in that; I wanted to write fiction that would linger in the reader’s mind. Ironically enough, I did that by self-consciously revisiting the genre’s central tropes and trying to dig into them. And I did that by investing in character, in trying to create figures whose fates would matter to the reader.

Carroll: I’d been curious about the aspects of The Fisherman that responded to Moby Dick. How did you filter aspects of Melville’s narrative into yours without it necessarily overpowering the story you were telling? Were there any aspects of Melville’s novel that you wanted to touch upon but were unable to?

Langan: When I first returned to writing horror fiction in earnest, I had this idea that I would write a number of stories that were responses to canonical American writers/texts; privately, I borrowed D.H. Lawrence’s title and called them my Studies in Classic American Literature stories. So my early stories focused on Henry James’s work, because I’m a big fan of his: The Turn of the Screw, What Maisie Knew, and “The Jolly Corner” in particular. But I also wanted to do something with Moby Dick, because it’s a book I love, one of those texts where you feel the writer is trying to cram the whole world into it. I didn’t want simply to rewrite Melville’s narrative, maybe substitute a monster for the whale; rather, I wanted to reshuffle its elements, to look at the novel as if through a kaleidoscope. I hoped such an approach would help my novel to avoid falling into either pastiche or parody. As I worked, I continued to sift through Moby Dick, trying to keep in touch with the narrative. I did think it might be nice to have a couple of extra stories in my novel that would have showed Dutchman’s Creek and the Fisherman in a different light–much as Melville does with the whale in some of the later chapters in his novel–but I decided I wasn’t trying to cram the whole world into my book, so it was okay to let those things go. The funny thing is, when I look over my novel now, I realize that there are all sorts of places where it coincides with Melville’s that I was in no way conscious of while I was writing. As an example: I’ve always loved the scene in Moby Dick where Ahab baptizes the harpooners’ weapons with blood. There’s a moment deep in the heart of my book where a group of characters engage in a similar act involving weapons and blood. It makes me think that I internalized Melville’s book even more than I knew, which, given the nature of my project, is reassuring.

Carroll: A lot of your fiction deals with the aftereffects of trauma–whether it’s the tragedies that befall both Abe and Dan in The Fisherman or the PTSD faced by several characters in the title story in The Wide Carnivorous Sky. Balancing the emotional realism of these with more horrific and fantastical elements seems like a substantial challenge–how do you keep the two in balance?

Langan: I think that without the emotional realism, the fantastical aspects of the story don’t have any real weight. At the same time, the fantastical elements give the emotional realism a kind of depth of metaphor from which it benefits. In order for them to function together in a story, it seems to me essential not to distinguish between the two of them, i.e. in the case of my stories, not to think of the tragedies/PTSD as real–with the attendant value that places on them–and the fantastical elements as unreal–with the consequent value that places on them.

…the fantastical elements give the emotional realism a kind of depth of metaphor…

As far as the narrative is concerned, both have to inhabit the same reality, to have the same weight. You don’t want to see one in terms of the other. The moment you start to think, “Look at this clever trope I’ve constructed for loss,” or, alternately, “Boy, these emotions make some nice window-dressing for my cool monster,” you’ve sacrificed a certain richness that I’d rather try to achieve.

Carroll: Near the end of The Fisherman, there’s a brief image that readers of the novella “Mother of Stone” will find familiar. Is that coincidental, or are you working towards creating a unified setting for some of your fiction?

Langan: It’s intentional. As of this writing, I’ve published a good number of stories that have yet to be collected; at least another two books’ worth, after the collection I have forthcoming this fall. In these stories, I’ve been drawing connections, both among the stories themselves and between my work and that of other writers, especially that of my good friend, Laird Barron. I suppose I have in mind the kind of intertextuality you find among Balzac’s fictions, or Faulkner’s, or Stephen King’s. There’s a sense of a world behind the individual narratives, a shared universe (or even multiverse) that lends them an additional sense of depth.

Carroll: How did you and Laird Barron first meet? Did you know from the outset that you’d develop such a personal and literary affinity?

Langan: Laird’s first story in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction appeared the month after my first story in F&SF. After Laird’s piece appeared, Gordon Van Gelder, who was editing the magazine at the time, sent me an e-mail telling me to check out Laird’s story if I hadn’t already, he thought there was something to it I would appreciate. Gordon was right. Following that, Laird and I struck up an e-mail correspondence that was almost nineteenth century in its formality. From the start, I responded to the ambition and the integrity of what he was doing; he was easily one of the most exciting writers of what I guess you would call my generation of horror writers–and considering that’s a group that includes Nathan Ballingrud, Glen Hirshberg, Sarah Langan, Livia Llewellyn, and Paul Tremblay, among many, many others, that’s saying something. Eventually, we talked over the phone, then roomed together one Readercon. Our friendship was immediate, easy, and profound; really, it was like meeting this other brother I hadn’t know I had. I think it was during one of those early phone conversations that we first hit on the idea of making connections between our stories. I suppose we had in mind the kind of exchanges the old Weird Tales writers had participated in. I’ve said before that Laird is one of those writers who keeps me honest, someone whose work is of such high quality it causes me to up my own game.

Carroll: Is there a particular strain of horror fiction that frightens you the most? Do you generally find yourself tapping into your own fears when you write about the supernatural, or exploring something more conceptual?

Langan: I think any story has the potential to be frightening; though sometimes, it’s only after I’ve finished reading something and am reflecting on it that it has its full effect on me. There have been times I’ve been discussing a story I read literally years before with one of my friends and, in recounting the narrative, I’ll realize how truly scary it was. As far as my own work goes, there’s always a great deal of myself in what I write, including what frightens me. Sometimes, I’ll begin with things I’m afraid of–suffocation, say, or the loss of a loved one–other times, I’ll discover the horror of what I wrote once it’s done and I have some distance from it. Actually, that happens quite a bit: I’ll think about some element of the story that I was particularly pleased with while I was writing it, and see how awful it is. At the same time, I try not to lose sight of what I guess you might call the big picture, which is a view of horror fiction as the fiction of un-ease, of what Stephen King called “a pervasive sense of disestablishment, a sense that things are in the un-making.”

Carroll: For the last question, I wanted to move away from the conceptual and the literary a bit. You’ve made specific references to Scotch in some of your fiction, and I’m curious–do you have a particular favorite?

Langan: I’m a big single-malt fan, and am always happy to try something new. I’m quite fond of Talisker, but there’s a lot to be said for Auchentoshan and Laphroaig, as well. I’ve had the Glenkinchie Distiller’s edition, and that’s very fine, too.