interviews

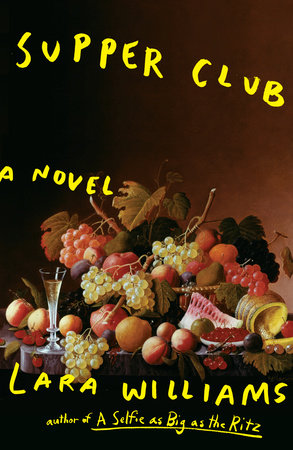

“Supper Club” Imagines What Could Happen if Women Unleashed Their Hunger

Lara Williams envisions a safe space where women don't have to pare themselves down to fit society’s ideals

The belief that women should be small and unassuming is so culturally ingrained that it’s normal for women to force themselves to stop eating when they’re still hungry, to stay quiet while someone else in the room speaks up, and to question whether they deserve more; not just food, but money, sex, power, autonomy, and space. But what would happen if a woman spent her energy asserting, rather than minimizing, herself? How difficult would it be to reclaim her body and her desires as her own?

Lara Williams confronts these questions in her debut novel, Supper Club, which tells the story of a young woman named Roberta who reaches her thirties “afraid and yet so desirous of everything.” For Roberta, fear typically wins—until she meets Stevie, an unapologetically brash artist who encourages her to reclaim her appetite. The two women start Supper Club, a traveling bacchanalian celebration where women can eat, drink, talk, dance—exist—in a completely uninhibited way.

Supper Club will resonate with any woman who has ever tried to pare herself down to fit society’s ideals, but it’s not limited to physical hunger; Williams embraces a range of timely issues from sexual assault to female friendship with engaging openness and humor. Supper Club also makes a case for the joyful side of indulgence with detailed meals reminiscent of Heart Burn by Nora Ephron or Sweet Bitter by Stephanie Danler.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Williams over email from her home in Manchester, England about how women inhabit space, air-conditioner bias, and the gendered way that public spaces are designed.

Carrie Mullins: In Supper Club, a group of women throw tremendous, bacchanalian feasts in rotating locations across a city. Where did you get the idea for the club?

Lara Williams: I knew I wanted to follow up on the idea of how women inhabit space, something I’d thought about in my short story collection A Selfie as Big as the Ritz, but to do this in a more focused way. And I was also interested in this sort of primal scream or exposure therapy theory of aggressively and almost hysterically leaning into something that makes you anxious. For a while, I have been convinced the cure to my very irritating capacity for shyness is to take an improv class. And I remember listening to the Kanye West album Yeezus a lot when it first came out, and thinking it was interesting it was written just before he got married. Like there was some necessity for this frenetic, libidinal but completely clear-eyed exorcism before he settled down. Supper Club is perhaps similar to that: this excessive embodying of something in order to achieve a more neutral relationship with it.

CM: Appetite is a key theme in this book. I often thought of Haruki Murakami’s line: “I never trust people with no appetite. It’s like they’re always holding something back on you.” At Supper Club, the women plan to indulge in food but end up letting go of all inhibitions. How do you think about this relationship between our physical appetite and our whole selves?

LW: I really like that quote. It reminds me of the short story “Starving Again” by Lorrie Moore, and there’s the quote: “That was the thing with hunger: It opened something dangerous in you.” The story is about two friends meeting over dinner and they are both these tightly wound balls of absolute need, having this nervy, truncated conversation, too afraid to order anything particularly substantial off the menu lest they reveal the almost deranged desperation and extent of their needs and appetites.

I think revealing an appetite for anything, really, makes you extremely vulnerable. But especially anything animal and basic, like food or sex or companionship. And I am perhaps a little suspicious of people who will not reveal any level of vulnerability, so I do relate to Murukami’s quote. It does sit a little at odds with his tendency to emphasize the slightness or wanness of his female characters, however.

CM: Roberta in particular struggles with the dichotomy between her “bottomless hunger” and her inclination to be unobtrusive. Likewise, she sometimes enjoys being in a more conventional relationship or her mindless fashion job and at others she feels dissatisfied by these things. You portray how complicated it is to navigate our own desires, especially as women, when we’re so surrounded by messaging that it’s not always clear what’s being forced on us and what we genuinely want. Was it important to you to embrace this conflict on the page?

LW: One essay I read while writing Supper Club, which really stayed with me, was “Hunger Makes Me” by [Electric Literature’s editor-in-chief] Jess Zimmerman, in which she talks about priding herself on being a low maintenance girlfriend. She talks about there being a strange shame attached to wanting effort from a man you are in a relationship with. And I feel like I wanted to explore two levels of desire in Roberta—her more primal appetite for food, sex, nourishment, companionship—but also a more intellectual or emotional need for a stable relationship with a man who treats her kindly, or for secure and rewarding work. She finds them generally incompatible, and finds both broadly impossible to ask for, and even shameful in asserting that’s what she desires.

CM: I recently read that most offices are air-conditioned to a temperature that is optimal for men and too cold for women. Yet while many of us have bemoaned the requisite summer office sweater, we don’t think about the AC as something that might be biased—or changed. In many ways, Supper Club is asking us to stop and consider our surroundings. Can you talk a little about engaging with the issue of space?

Revealing an appetite for anything makes you extremely vulnerable. But especially anything animal and basic, like food or sex or companionship.

LW: Yes, I am aware of the AC bias! When writing Supper Club, I was reading a bit into feminist geography and thinking a lot about how women engage with public space. There are statistics suggesting women make more trips on foot and cover more ground than men (and also use public transport more, except trains). And yet public space is rarely designed with women in mind, with inadequate lighting, narrow streets, not enough ramps for pushchairs, etc. An entirely well-meaning man recently gave me directions that involved using this dark, very lonely underpass, and I thought: a woman would definitely not have given me these directions without some kind of addendum. And even though it is most likely the underpass was perfectly safe, I felt uncomfortable and on-guard the entire time I was walking through it, which is ridiculous really. And I was also thinking about fatphobia and design, how public transport seats (and basically everything) are made with this presumed de facto thin sized person in mind. It was those kinds of frustrations that went into Supper Club.

CM: Supper Club made me laugh. I’m curious about your approach to humor and also your experience publishing a book that’s funny while also exploring serious issues. I’ve found that humor isn’t thought of as marketable in the same way for female writers as for men, though both genders have to contend with the same old cliché that literary books aren’t funny.

LW: I’ve always been interested in how women often package stories of sexual harassment or even sexual assault as, like, funny stories (myself included), and I wondered what the impetus of that is—is it subdued rage or packaging anger in a more amenable guise or trying to make people comfortable while still trying to communicate something uncomfortable? Though I sometimes worry humor is a concession, a way of sneaking in the idea that you are not taking yourself seriously, perhaps, so no one else should?

I’m currently drafting a new novel and I set myself the task of not writing any jokes in it, but within literally the first paragraph I had already failed. The majority of my favorite contemporary writing by women has humor woven into often seriously themed novels / stories – A Visit From The Goon Squad, Department of Speculation, Convenience Store Woman, Mary Gaitskill or Carmen Maria Machado’s short stories—though they’re not really contextualized as “funny” writers, which I also find revealing.

CM: Throughout the book you incorporate detailed passages about cooking, and I was reminded of Heartburn by Nora Ephron. What was your inspiration for these sections?

LW: The first passage I wrote was the section on caramelizing onions. I wanted to write something about the patient, slowed down, embodied experience of following a recipe, and to also spend time going into the methodical detail of this. And also almost testing the reader’s patience slightly in doing so in quite a laborious, meticulous way—which seems to be a somewhat male writerly trait.

But after that, I liked the idea of including not quite recipes, but either meditations on recipes, or embodied experiences of following a recipe. So for example, there is a description of Thai red curry, which is quite a simplified and anglicized version of that recipe, which comes at a point where Roberta is hurrying towards settling down and getting a sense of apparent normality with her boyfriend. It felt quite a domestic and slightly self-satisfied recipe, and also the sort of thing you might make to perform being an urbane, together grown-up. I wanted these sections to sit thematically with certain moments of the book.