essays

Swimming Made Me Gay

How my sport and the literature of water made me comfortable in my own skin

Swimming made me gay.

That’s not true, but I like the way it sounds. It finally lets me combine the words and the water, the sport and sexuality, that have made up my life, that have engulfed and carried me.

The first person to call me a lesbian was the mother of one of the girls on my swim team growing up. The girl lived up the hill and around the corner, and sometimes we carpooled together, inventing songs in the back seat. On hot days after early morning practices we wasted time watching educational cartoons, and hiding from her older brother and his guitar. Was that something like a crush?

One day, not so different from the rest, we decorated our plastic team water bottles with permanent marker. We wrote out all the usual slogans: Eat my BUBBLES! Swim FAST!! Kick BUTT!!! And, inside a heart, my neighbor wrote our initials, with a little plus sign nestled in between.

That was her crime. Or rather, my crime. Her mother called mine, after scrubbing off the marker with acid, and yelled. I didn’t learn about this phone call until years later, so I can only imagine how it went. “How dare you let your lesbian daughter in my house, in the locker room, in the pool with other girls?!”

In hindsight, the other odd comments she made over the years began to make sense. The time she accused my family of spying when we took the blind curve in front of their house too slowly. The time she told me I ate too much, and too often. The time her husband wouldn’t let me leave the table until I had finished everything on my plate. She wanted to keep us at arm’s length, to correct my behavior in front of her daughter so she wouldn’t turn out like me. It wasn’t my queerness (in all senses of the word) that was a problem, per se, but the idea that it might be catching.

It wasn’t my queerness (in all senses of the word) that was a problem, per se, but the idea that it might be catching.

This wasn’t the only incident with the team provoked by my version of girlhood. I stuck out. The other swimmers in the locker room wore designer brands, straightened their hair, put on makeup. I composed outfits entirely out of different shades of orange.

There’s me, maybe fourteen, in front of the computer after a long workout, having, for once, co-opted our dial-up connection. I got a chat invitation from a screenname I didn’t recognize, someone who said they were on the team with me. I accepted, and a few messages in, she said: “You have so many pubes, lol.” I demanded she reveal herself. “Who are you? How did you get my screenname?” After a few evasive answers, I got a message that said, “You’ve been tricked! This is a robot! The first few messages were programmed, but the rest has been computer generated!” The exclamation points made me cry even harder, as if the programmer took pride in this tool created for bullying. I vowed to renew my vigilance with shaving cream and a razor.

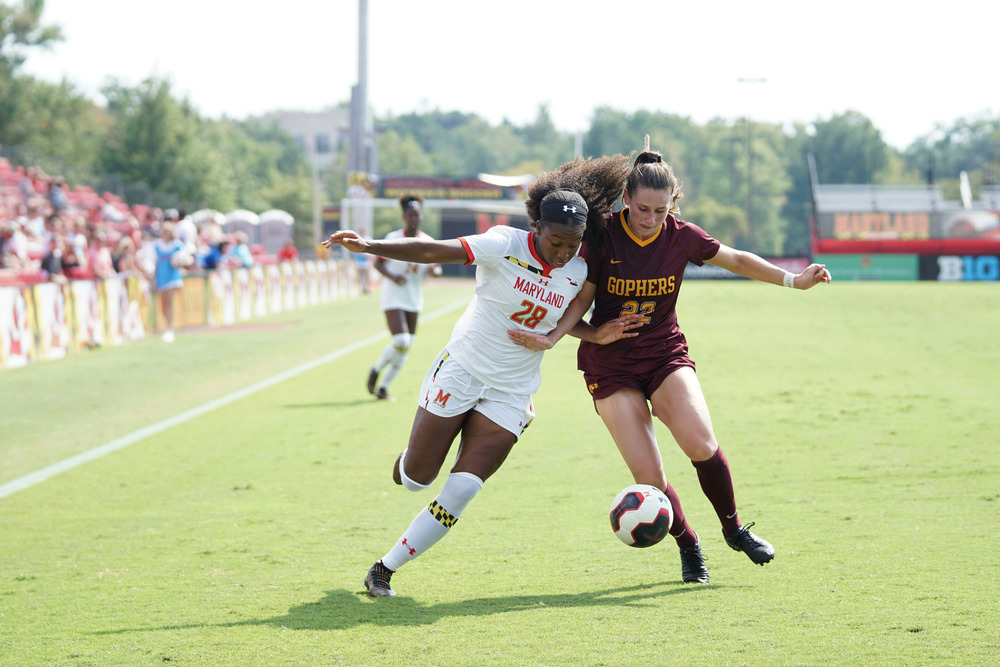

This was just one of many torments — the girls who lined up along the wall so I couldn’t climb out of the pool, the ones who told me they couldn’t imagine me dating — that served as a reminder that there’s more to competitive swimming than body meets water, more to being an athlete than physical practice.

You put on a gender-appropriate uniform. You rise for the national anthem. You chant fight songs. These little routines require patriotism and gender conformity and a healthy competitive spirit, as if a team were a training ground for the military. Was it possible, then, to be both an athlete and a queer, unkempt hair and all?

I grew up in Pittsburgh, home of the Steelers and their fiercely loyal fans. The first thing to greet visitors at the airport is a statue of Franco Harris, who I was taught at an early age made one of the most famous plays in football history, the Immaculate Reception. He sits right next to a statue of George Washington, who helped drive the French out of our city when it was just a Fort. Together they are presented as our city’s two great heroes, each responsible for putting us on the map in their own way.

Raised in this town, my sister became a convert. She followed their seasons, stayed up well past her bed time to watch their games, and jumped at the chance to go to a game, or, better yet, training camp.

Me, on the other hand? It wasn’t my thing. When the games came on and my sister started shouting at the TV, I would run upstairs to my room and shut the door. I did learn to speak passable football, but, when pressed, I can’t really explain what the Immaculate Reception actually is. I can’t name any of the players, either, except the ones who had been in the news for their off-field activities: Michael Vick. Ben Roethlisberger. Peyton Manning. Ray Lewis. They taught me from an early age that controlled bursts of on-field violence were often tied to real-life episodes.

I wasn’t surprised to learn recently that football has the highest number of convicted players at the professional and collegiate level of any sport, and nearly half of those are for violent crimes. That number doesn’t even include many of the names I can recognize, since many of those men were never convicted.

It’s no wonder that we have yet to see an active pro football player come out.

It’s hard to tease out the separate strands at play here — questions of race and class and the impact of fame go hand-in-hand with questions of gender. But there are traditional masculine ideals at the center of all this — a strong man who fights on the field like a gladiator and sometimes can’t shed that role at home; and a man on the other side of the screen, watching with a beer in hand. It’s no wonder that we have yet to see an active pro football player come out.

When I left the city of black and gold, I tried to find a different way to be an athlete, a swimmer, a body that moves through the water. I picked the college that had the best academics and the worst swim team.

Other teams in our conference opted for matching warm-up jackets, or even identical braids with matching hair ribbons, and they would emerge from the locker rooms clapping hands in unison like an approaching storm.

We couldn’t be bothered.

We tried to show up on time, but if class got in the way, we didn’t. We wore what we wanted, even if that was a hoodie that zipped up so far it covered your face. Sometimes, before a meet, we would ironically chant, “Fight fight for the inner light! Kill Quakers, kill!” And in preparation for the final meet of the year, we would dye our hair neon shades of pink and blue and green. We looked more like washed out clowns than gladiators.

I came out with the help of one of these teammates. We sat on deck icing our shoulders, discussing our crushes out of earshot of our coach, and she handed me the word lesbian like someone proffering half a sandwich at the misfits table. But we weren’t misfits, really. Or maybe everyone on the team had been one somewhere else, and now, finally, we were able to come together. No one cared about your grooming habits, or your sexuality. One year we had a lesbian coach, the first I had had in over a decade of competitive swimming, and several more teammates have come out after college.

The Queer Erotics of Handholding in Literature

That’s when I began to wonder, did swimming make me gay? Or rather, is there something queer about swimming?

Exhibit A: IGLA, the International Gay and Lesbian Aquatics association, is one of the biggest queer sports leagues in the world. I joined a team right after college, and it was a revelation to talk to so many queers with locker room horror stories. The men still lift up my arms to exclaim about my hair, but I take it as a sign of curiosity rather than scorn.

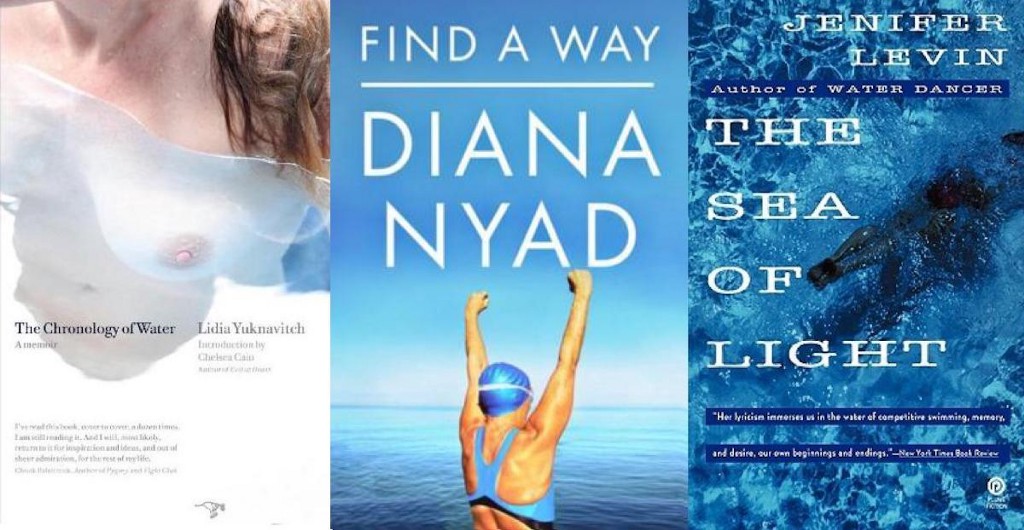

Exhibit B: Books by queer swimmers, most of them women, seem to be flourishing — The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch, Find a Way by Diana Nyad, The Sea of Light by Jenifer Levin. It’s not just that the writers are queer. Their non-linear narratives are in opposition to the celebrity athlete memoir. Rather than claiming victories and extolling the value of hard work, they float, riding waves of memory and feelings churned up by the tides.

Their non-linear narratives are in opposition to the celebrity athlete memoir. Rather than claiming victories and extolling the value of hard work, they float, riding waves of memory and feelings churned up by the tides.

In her memoir, Lidia Yuknavitch writes, “All the events of my life swim in and out between each other. Without chronology. Like in dreams.” She calls this new timeline “the chronology of water” and employs it to tell her own life story. She touches on everything from first dates in the pool to being a member of Ken Kesey’s writing group to her difficult experiences with abuse, addiction, and miscarriage, rarely reverting to the actual lived order of things to tell the story.

Long-distance swimmer Diana Nyad’s memoir Find A Way tells the slightly more linear story of the sixty-year-old’s triumphant swim from Cuba to Florida. And yet water’s chronology carries her away right in the first chapter, where she pairs a scene from one of her failed attempts to complete the swim with a memory of standing on the beach at age nine with her mother, squinting toward Cuba. It was something she remembered while swimming. The lesbian swimmers in Jenifer Levin’s campus novel The Sea of Light also remember their pasts in the pool, and they show up every day not just to compete and to win, but in hopes of healing their traumas.

And then there’s Moby Dick. In all the myriad analyses of our Great American Novel, I don’t think anyone has come out and said it: Moby Dick is the greatest queer swimming book of all time. The homoerotic elements of the novel have been catalogued elsewhere — what I’m interested in is the swimming.

Sometimes it’s the whales, gliding through the vast ocean, and sometimes it’s the men, floundering, or even drowning. No matter who is doing it, the book is filled with gorgeous passages about creatures moving through water, and the narrative structure itself ebbs and flows, the ancestor of today’s swimming books. The repetition of sweltering mornings and endless stretches of water remind me of the routines of competitive swimming: early morning mist rising over the pool, countless laps swum over the same terrain, all that effort never taking me anywhere. And Melville’s digressions into the history of whaling? I know all too well that when faced with so much water and so much solitude, the mind will wander. Adrift, it’s easy to let the water carry you away from what it means to win and lose, to be strong, to be a man or a woman, or simply a body in the water.

Moby Dick is the greatest queer swimming book of all time.

Even with all this — the queer swim team and the queer books and the democracy of water — there’s something that keeps competitive swimming from truly being queer. It’s still a sport. There are still regulations and officials and registration fees. There are still young girls who police one another’s bodies, and their budding sexualities. How can something built on strength and competition and scrutinizing the body’s performance be queer?

It goes back to the decades-old question of what is at the heart of queer activism. Are we fighting for acceptance into the existing structures (marriage, the military, sports) or to dismantle those structures entirely? Even a queer sports league is recreating existing structure, albeit in parallel. This separatist revision of mainstream sports still leaves lots of folks on the outside: athletes of color, athletes with disabilities, transgender athletes, anyone who can’t pay the registration fees.

On summer mornings in New York City, and even into the late fall and early spring, you can spot little fluorescent globes bobbing in the water along the shores of Coney Island. Sometimes they appear in small pods, and sometimes there’s just one, making its determined way down the coastline. These are swimmers, but not like I’ve ever known. Clad in brightly colored caps to stand out against the blue gray of the waves, open water swimmers have left behind the confines of the pool, the rules and regulations, so that nothing stands between them and the thing they love.

I decided to join them a few years ago. On my first swim, I popped up every few minutes just to exclaim about the cold or because I thought I had seen a shark (or run into a jellyfish or, more likely, some bit of floating trash — a newspaper, a grocery bag, a used condom) or to gaze out at the Rockaways and hope I didn’t get swept away. I had never felt so small, so powerless. It was no longer an even 14 strokes from one end of the pool to the other. One hundred strokes could either take me from one jetty to the next, or nowhere at all, depending on the current. I emerged from the water with a green sea beard of algae on my face, and I was hooked.

I emerged from the water with a green sea beard of algae on my face, and I was hooked.

Just as the sport is upended, so are the unspoken rules of the community. It doesn’t matter who is fastest. To me, the kings and queens of the beach, our adult equivalent of the popular girls, are the ones who have completed the most impressive feats of endurance — they’ve swum MIMS, a marathon around the entire island of Manhattan, multiple times; they swim in the ocean in 40-degree weather; they know the tides and the currents. There’s no coach, no set workout, no fixed practice time. There are few six packs here, and little vanity. I shudder to think what my high school teammates might have said about the motley crew gathered on the beach, about our swim suits, about our faces, white with zinc.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

And then I laugh to think that it doesn’t matter at all. If there is truly a queer version of my sport, this is it. Inherently gendered ideas of domination and victory are swept away, and something almost undefinable takes their place. There’s still discipline and rigor — it takes months of training to complete the more than 26-mile loop around Manhattan — but it’s hard to define what it’s all in pursuit of. Who is the opponent? Maybe it’s your own self, as you try to test the boundaries of your endurance, or maybe it’s the sea and all its elements. The salt, the currents, the cold.

Maybe it’s not about an opponent at all, but about the journey, and the encounters with the self that the solitude of the journey brings.

When I see these swimmers, when I swim among them, I think again of Moby Dick. One of the crew, off in pursuit of the white whale, falls overboard and nearly drowns. Down at the bottom of the ocean, he sees God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom.

Maybe it’s not about an opponent at all, but about the journey, and the encounters with the self that the solitude of the journey brings.

I read this passage in delight. To imagine! Words, and the very fabric of our existence, spun deep underwater on the ocean’s floor. No wonder I found the word lesbian by the pool. No wonder the water calls into question athlete and team and competition. Is it these words that bring us together in motion, or the mere fact that together we parse the warp and weft of the water?

If someone gave me a seat at the loom, I would weave new meanings into old words: Mermaid. Dolphin. Siren. Pod. Maybe I could be the one to invent the word for a group of mermaids, swimming close together, but each at her own pace.