essays

Sylvia Plath Looked Good in a Bikini—Deal With It

Uproar over an image of the poet on the beach shows that we’re not ready to let literary women be people

There is an oft-repeated story in most biographies of Sylvia Plath, concerning her return to Smith College after her suicide attempt and subsequent hospitalization. It was the start of the 1954 spring semester, and Plath was meeting, for the first time, the young woman who had occupied her dorm room during her illness — Nancy Hunter, later Nancy Hunter Steiner, who would go on to become Plath’s close friend, and pen a short memoir about their relationship, A Closer Look At Ariel.

As the story goes, Hunter had spent her time in Sylvia’s room feeling “haunt[ed]” by its former occupant. Plath had taken on a legendary status at Smith, thanks to both her brilliance as a student and her suicide attempt. According to Steiner, “…as the months passed I grew familiar with the details of the Plath legend through the speculative gossip that raged at the mention of her name.” In Plath’s absence, Hunter formed an image of her as a “girl-genius… as plain or dull or deliberately dowdy, a girl who rejected all frivolity in the pursuit of academic and literary excellence.” Now, meeting this mysterious figure for the first time, at a campus luncheon, Hunter was so taken aback by Plath’s appearance that she blurted out, “They didn’t tell me you were beautiful!”

This snapshot from Plath’s college years already contains the amalgamation of myth, rumors, misinformation, and surprise turns that has hallmarked Plath’s literary and personal legacies since the publication of Ariel in 1965. It’s all there, from the sudden mysterious disappearance (“speculative gossip, [rage] at the mention of her name”), to the wild projections of the missing woman (“dull…deliberately dowdy”) to the gobsmacked reactions to Plath’s actuality (Surprise! She’s beautiful!). Plath is always either under– or overwhelming her readers — Janet Malcolm famously wrote in The Silent Woman that Plath “disappoints her” in photographs. She’s looking for a red-haired witch who “eats men like air,” and all she gets is this lousy housewife, clutching her babies, hair done down in braids. Jessica Ferri, writing of handling those very braids when she worked in special collections at the Lilly Library in Indiana, exclaims, astonished, “There was so much of it!”

In my own life, more than once, I’ve been asked “Who’s that, there, on the cover?” while handling my dog-eared copy of Plath’s Unabridged Journals, which plainly state her name. When I reply, “That’s Sylvia Plath,” the response is almost always the same — it can’t be. They are looking for a magical witch, a goth girl, a myth. The image of Plath, smiling in her Smith graduation robes, causes cognitive dissonance and, ultimately, disappointment. It’s the same cognitive dissonance we, as a culture, collectively suffer about Sylvia Plath, and indeed about any woman lauded for her intellect who also has the nerve to inhabit a body: That’s her? Isn’t she a little too beautiful? Isn’t she not beautiful enough?

This pattern plays out in reaction to Plath’s image each time there is a new Plath publishing “event.” The latest is the U.K. edition of Plath’s Collected Letters, which sports as its cover art a photograph of a twenty-something Plath grinning for the camera in a white bikini. I first became aware of the cover, and its accompanying outrage, in a Facebook post from a well-known American poet, in which she (and, in the comments, other well-known American poets) expressed deep anger and exhausted frustration at the inherent sexism the choice apparently symbolized. Last week, I woke to Cathleen Allyn Conway’s piece about exactly this, in which she not only critiques the cover art for the Letters, but also that of a half-dozen other Plath books.

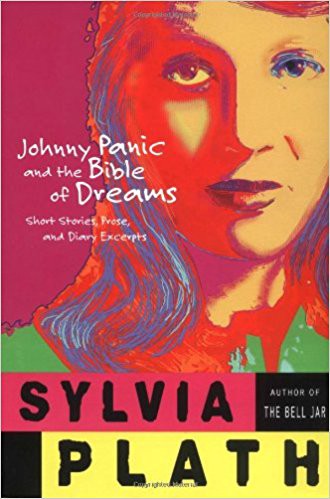

As I write this, all of those books, sometimes in multiple editions, stare back at me from between their bookends on my desk, reminding me that the politics of Plath somehow always end up as the politics of reduction and essentialism. Conway notes that the same bikini shot appeared on the cover of a recent edition of Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, a collection of Plath’s prose; she lumps this cover in with a widely criticized edition of The Bell Jar as “proto-chick-lit” imagery. Presumably she would prefer covers like that of an earlier edition of Johnny Panic, whose psychedelic colors underline the idea of “mental illness” while also reinforcing the popular conception of Plath as a magical witch. While Conway does write “the rationale is that pictures of smiley Plath counterbalance the darkness in her work, lending extra tragedy to her illness and death,” she dismisses the notion because “this kind of correlation is not made for male authors.” This assessment fails to take into account another possible reason for including photographs of Plath that aren’t, frankly, morbid: they paint a fuller, more accurate picture of the living woman, rather than highlighting her tragic death.

In his introductions to Johnny Panic, to the heavily abridged 1982 edition of Plath’s Journals, and to her Collected Poems, Plath’s estranged husband Ted Hughes claims that Plath had one, singular “true self” which she hid from everyone but him; her poetry and prose, he says, were an attempt to put this “true self” into writing. Ariel, Hughes once said, “is just like her, but permanent,” an incendiary statement that would invent and bolster two absurd facets of the Myth of Sylvia Plath: that the “I” of the Ariel poems was the “true” Plath, and that the book itself was a finished thing — a mausoleum which you could enter at will, encountering the dead woman at every turn, enshrining one bleak version of Plath in the cultural mindset. Conway rightfully takes Hughes and his sister Olwyn to task in her piece, pointing out that they actively tried to construct Plath as an hysterical lunatic in the wake of her suicide; there can be no doubt about that. Unfortunately, in her assessment of Plath’s image, her “true” self, Conway is netted in the same dull trap that Hughes built and set in his public writing about Plath. According to Conway, Plath had one definitive look that was deeply connected to her true self, and it wasn’t a blond woman in a bikini. She quotes a 1954 letter from Plath to her mother, Aurelia, that states “[my] brown-haired personality is more studious, charming and earnest,” then extends this notion with her statement that, “We know brunette Sylvia was how Plath wanted to present herself.”

And herein lies the real problem: We don’t actually know this at all. One line in a letter to a worrying mother in Eisenhower’s America (who, as other texts describe, was shocked and dismayed when Plath dyed her hair blond in the first place) does not a “true” self prove. Moreover, this furthers Hughes’ dangerous idea that Plath, or any of us, has a single, definitive “self,” an idea we visit almost exclusively upon the heads of women writers. We celebrate Whitman’s celebration of himself, with its numinous notion that “I am large, I contain multitudes.” We have no problem reconciling the idea that he was both queer and a hetero-braggart who claimed to have fathered six illegitimate children, yet we take to task a photograph of a bikini-clad Plath in her college years — as though she could not possibly be both the genius she was, and a woman who was body confident, sexy, happy to smile for the camera.

The dangerous idea that Plath, or any of us, has a single, definitive ‘self’ is an idea we visit almost exclusively upon the heads of women writers.

Conway notes that Robert Lowell, Plath’s contemporary, is always pictured sitting gravely in a library or a study, with a back wall of books, as though this is the only way we can understand a writer or take them seriously. But to understand Plath at all is to know her as a woman of her time, which demanded that a woman of Plath’s race and class choose a single narrative — marriage and family — and stick with it, as she so famously chronicled in The Bell Jar. In pursuit of this end, women had to be experts, if not slaves, to material culture, as exquisitely documented in Elizabeth Winder’s Pain, Parties, Work. To deny Plath’s love affairs with beautiful things is to deny the reality of the conditions of her life.

But it’s also to deny the part of her personality that was not bleak, that was not morbid, that was not dictated by her illness or her marriage. She loved Revlon’s “Cherries In The Snow” lipstick and nail lacquer, and always dotted her clothes with a pop of red — red ballet flats, red scarves, the famous red bandeau headband Hughes ripped from her hair the first night they met, as a souvenir. These were a result of the world she occupied, but they were also extensions of her passion for aesthetics, for fashion and fine art — the current Plath exhibition at the Smithsonian contains the multitude of excellent paintings she produced in the Smith College studios. When Esther Greenwood, Plath’s Bell Jar protagonist, goes to the roof of her downtown Manhattan hotel and tosses the beautiful clothes she took with her for her summer job as a guest editor for a fashion magazine, item by item over the sleeping city, she isn’t doing so because she’s become some kind of ascetic, or because she now understands her true self, and beautiful things have nothing to do with it. She does it because she lives in a world that demands she be either/or, that makes no room for both/and. Rather than choosing a self, she begins the terrifying process of giving up any self at all, which culminates in a suicide attempt.

I’d like to believe that by now, the room for both/and exists, but reactions to the image of Plath in a bikini — which, incidentally, is a holiday snapshot taken by a boyfriend, not the calculated and manipulated result of a photoshoot — bode otherwise. This picture of Plath is not, as Conway claims, “a visual antithesis to the ambitious, intellectual poet.” It was taken, in fact, the summer she dated Gordon Lameyer and Richard Sassoon, who loved her equally for her physicality and her extraordinary intellect, and whom she loved for those things, in turn. The dialogue between the carnal and the intellectual was one Plath started as a very young woman, and did not give up until her death. At no point did she see these as mutually exclusive; she often described her love for Hughes as being the force it was because he embodied the physicality and intellectualism and artistry she both possessed and craved in another.

The reality, and it’s astounding to me that I have to write this sentence down, is that we can take a writer who wears a bikini seriously.

The reality, and it’s astounding to me that I have to write this sentence down, is that we can take a writer who wears a bikini seriously. I have three in my closet;, the most recent of which is a vintage-inspired red-halter. I bought it because I love red; I love red partly because I love Sylvia Plath. I wear “Cherries In The Snow” lipstick to the classes I teach, to parties, to intimidating meetings with condescending men, and when I do, I invoke her, just a little bit — for inspiration. For luck. For permission, which she gave me, which she gives me — to be brave. To try and astound. To say the things no one wants to say, or hear. To be beautiful, and to be smart, and sexual, and to never, ever fall into the foolish trap that these cannot coexist.