interviews

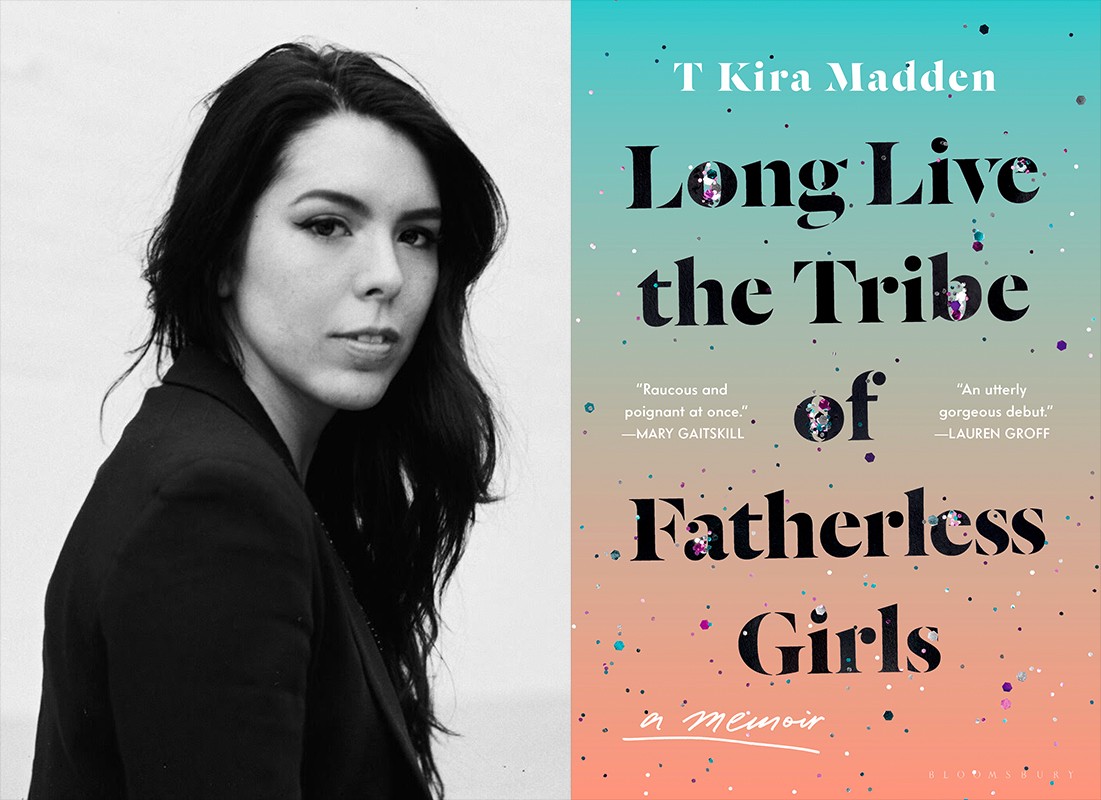

T Kira Madden’s Memoir Is a Love Letter to Misfits

The author of “Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls” on navigating family darkness and yearning for answers

“For instance: the women.”

These words open T Kira Madden’s debut memoir, Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls. They seem innocuous at first, nothing more than the descriptive facts of the cosmetic surgery commercial that played on loop during Madden’s early years. She recounts the details of the commercial: the women, the droplets of sandy beach water and sweat that drip down their bodies, and the man who sings to them. Their beauty is his work, his pride, his joy. In her they spark envy, curiosity, desire. As Madden then transports you years into the future, planting you in the hours and days following her father’s death, you are immediately imbued with the knowledge that here — in this world, and in this story — the women are the anchor. The women are safety. The women are home.

In essays written with raw and fearless prose, Madden asks the questions to which we all seek answers. In so doing, she honors fathers and mothers and families; the ways they love, and the ways they fail. What makes Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls so exceptional is the compassion Madden brings to the page. She writes in search of answers because that is what we, as humans and writers, do. But she does this all the while knowing that even in death, we are never really finished. The answers can never really be answers. And yet, we must find the semblance of them somewhere. Why not the women?

Dennis Norris II: I want to start by asking you about the beginning. Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls covers so much ground in your life, so many important, intimate, intense moments. I’m wondering if there’s a particular moment that you see as the germ for this book? Whether it’s in the book or not, I’m curious about a moment, a memory, a conversation, or an incident that planted the seed?

T Kira Madden: I began writing this book in the thick haze of grief just after my father died, though I didn’t know I was writing it. I was on assignment, asked to write about a Valentine, and, instead of a more traditional route, I wrote about my first love: a full-bodied mannequin I’d named Uncle Nuke. He lived with me growing up, and we were so inseparable I began popping his joints apart, carrying his hand around in my lunchbox. It took me months to realize that that mannequin was a way into my father. My father’s hands before he died, his bulging knees; I watched life leave my father’s body in a hospital bed, and grief came to me in those flashes of body parts. Uncle Nuke was my way of writing about it before I was ready to write about it.

DN: Did writing this book complicate your relationship to, and thinking of, your father? Did it simplify it?

TKM: My father was and always will be the giant of my heart. Same goes for my mother. My hope in writing this book was to render them as full as possible. As human beings packed with complications and contradictions and fury and nobility. My father was, at times, a monstrous and abusive drug addict who threatened to kill me with a baseball bat. He was also gentle, and funny as hell, and cried in the movie theater. He liked to Facetime me whenever I went to BLM or LGBTQ protests so he could feel like he was there (he was too sick to physically make it); he was brilliant and generous. Jo Ann Beard taught me this: you can’t create shadow without casting a light. Writing into my understanding of my father will never bring him back, will never come close to the person he was, but I’ve learned to honor that failure and appreciate both how much I know about him and all the ways in which I will never know him at all.

My father was, at times, a monstrous and abusive drug addict who threatened to kill me with a baseball bat. He was also gentle, and funny as hell, and cried in the movie theater.

DN: I feel as though the experience of reading this book is a lot like consuming a montage of secrets, of memories, of conjuring details from the memories of others, and questions — so many questions! I’m reminded of the five W’s of writing we learn about as kids: who, what, when, where, why. Only in this book these are like the questions of life: (Who is my father?) (What did my mother do?) (When did this happen?) (Where was I?) (Why — so many why’s?). How did you begin to make sense of all of this, both in life, and in the writing process?

TKM: What I loved about writing this book is how much the process you’re describing plays into the final section. We all have the stories we’re told about our lives, and the stories we tell ourselves. We narrativize our personalities and create our own story arcs because life is so messy and bat shit and mostly incomplete and unsatisfactory that we need to tidy it, to story it, to make it feel full and circular and interesting. I learned through writing this book that there is no getting your own story right; forget about anyone else’s. When you’re trying to wrangle every version of yourself and harness every refraction of light and shadow from lived experiences — experiences that change color with every subsequent recall — what you get is a mess. I hope this book is as true to telling the story as it is to the story itself.

DN: One of the words that came to mind early in my reading, and remained throughout, was the word yearning. There’s a really palpable sense of yearning from the outset, and as the reader moves through the book, it seems to transform from a trickle into a crescendo. Yearning for safety, for protection, at times to be seen. Has the process of writing this book, and the essays that make up portions of it, satisfied some of that yearning? Do you think that writing in general can help us find the things we search for?

TKM: Yes, the writing is the answer. I don’t write for myself. I write because I need dialogue. I write because I need people, or even one person, to hear me. To see me. To say “I see you.” I write for the chorus. This book is about all the places one reaches for love and compassion, and all the ways in which we fail in that reach. I’ve always found the deepest love and recognition and balm and even divinity in books and in art. So I’m here to nourish that act of connection.

DN: Do you find yourself wanting to control the narrative that people take from the book, about your life, your father, your family? Is there, in any way, a sense of “I’ve gotten it right or wrong,” and is that in any way related to reactions you’ve gotten from readers?

TKM: I do hope people close the book feeling like they’ve spent time with real people, people who have failed tremendously while doing the best they could. I don’t like the hero/villain narrative. I don’t like the clichés of thought that draw us towards binaries. I’m after the in-betweens, the nuances and complications behind human beings making the wrong choices. If I got to control one thing: I’d like readers who may not (think they) know any addicts to leave this book knowing them.

I do hope people close the book feeling like they’ve spent time with real people, people who have failed tremendously while doing the best they could.

DN: I would imagine that much of what you’ve written about in this book are things that continue to haunt you, right? We don’t just create something, and then put it in a box in the attic. There are new relationships, and there are new understandings of life-long relationships. Is there, anywhere in the process, a sense of completion, whether it be about the work, or about the lives that are intertwined with yours? Is that something you’ve sought at any point in your writing? An arrival of sorts?

TKM: I think a book has three lives: the first life is when it occupies a space in the writer’s mind before it’s destroyed by being put to paper. The second — the life that’s just ended for me — is the working, writing, editing, tormented love affair between writer and manuscript (and, if you’re lucky, great editors, too). After that final edit is made when it’s time to print, the book moves onto its third life, that is, the life my book will (I hope) share with readers. It’s no longer mine. It’s no longer alive, or breathing, or something to which I can return. I am grieving that but celebrating it, too.

Regarding the events of the book, the people in it, the moving parts — no, those will never be complete. What is completion? We’re not complete when we’re dead. Not even long after we’re dead, and mythologized, and spoken about, and half-remembered. My book does not capture or complete even a moment of time; time is a narrative construct.

DN: I know you primarily as a fiction writer because we studied together at Sarah Lawrence. How has it been different, venturing into nonfiction? Did it in any way inform your craft, or your approach to the page? Or is that something you’ve not given thought to?

TKM: I actually feel extremely fortunate to have studied and written fiction before writing or teaching nonfiction. The elements of fiction and story are often disassociated from nonfiction — basic toolbox skills like character building, story arcs, tragic and comic form, setting, dialogue, etc. In my nonfiction class at Sarah Lawrence, we read across genres in order to exercise those individual skills. Our job, regardless of “genre,” is to make a work of art and to make that art feel alive and true. We need these tools to do that; we are architects, building the scaffolding upon which our language and stories are hung. Experience doesn’t “bleed out of the typewriter” as some (mostly non-writers) may suggest. It doesn’t even flop onto the page like a dead fish. It’s built both mysteriously and scientifically.

Our job, regardless of “genre,” is to make a work of art and to make that art feel alive and true.

DN: Writing about family without calling the book a novel must have presented some challenges. Were you ever asked to alter the work because it’s about, and in some ways, reflects real people?

TKM: I think something we don’t talk about enough, something that shouldn’t be so mysterious, is the fact that nonfiction writers are usually required — legally — to edit our characters in order to protect their privacy. I’m not talking about changing their names; I mean changing major details and defining characteristics — appearance, family, race, occupation — edits that seemed impossible to me when I went through this process. This is both to protect the character but also, often, to protect the writer. (I don’t blame a writer for making these changes even if they’re not instructed by a legal team. Writing about real people can be incredibly scary; consider, for example, writing about an abuser.) Finding new characteristics to describe someone, characteristics that feel as true as possible without revealing who they are, is a whole separate skill set.

DN: I began to wonder about how you define family, how you see and feel and love and honor and critique your own family, particularly when you started writing about your brothers, and then your mother’s life prior to your own birth. Can I ask, simply, what does family mean to you?

TKM: I look forward to spending the rest of my life writing into this question. It’s the question that always brings me back to the page.