interviews

Chasing Dreams and Money in Dubai Amidst the Gulf War

Tania Mailk, author of "Hope You Are Satisfied," on writing a war novel where tourists are drinking cocktails at the beach and no one gets bombed

Tania Malik’s new coming-of-age novel, Hope You Are Satisfied, takes place in 1990s Dubai, during the lead-up to Operation Desert Storm. The story follows Riya, a twenty-something Indian immigrant sending money home to her family while working as a guide for “rinky-dink” tour company Discover Arabia. Riya has a fraught relationship with Dubai: she’s making money but has limited control over her circumstances. Her passport is kept in a safe in Discover Arabia’s office, “assurance against their sponsorship of [her] work visa.”

“There was no future here,” Riya says. “Wherever in the world we hailed from, our time in Dubai lasted only as long as our work visas remained active. There was no possibility of citizenship, no impetus to form lasting ties to the city… At the end of our time here, we were to return to our countries with buttressed bank accounts, back into the arms of the families we’d supported and the glorious houses we’d built with our Gulf money. Such was the pact.”

Riya’s coworkers comprise young people from various countries, “guest workers” trying to send money home, all trying to figure out their next landing place. While supporting their families and waiting to find out whether war will break out, the characters persevere in the traditions of young adulthood: they get drunk, get laid, and maintain difficult friendships. Riya’s best friend and roommate, Grace, has her sights set on Canadian citizenship. Riya, however, dreams of the U.S., and what a future for herself and her family could look like there.

When Riya’s boss’ boss—an import/export magnate named César Rodriguez who “harbored no ideology when it came to the sourcing and selling of any kind of merchandise”—offers her a dangerous opportunity she can’t financially refuse, she must decide how much she’s willing to risk, and for what she’s willing to risk it.

I spoke with Tania Malik over the phone about class disparity, the concept of “home,” and finding absurdity in times of violence.

Deirdre Coyle: Early in the novel, Riya says, “Everyone was speaking about ‘the events,’ but what I wanted to ask was how these events would affect me. While the residents of the city were overrunning the banks converting dirhams to US dollars, I didn’t have enough in my bank account to change into any useful currency.” Riya’s external circumstances are quite specific to Dubai in 1990, but I felt that her internal experiences—coming of age, her relationships, her family struggles—felt really universal. Could you say more about how you found that balance?

Tania Malik: When I was thinking about writing Riya’s character, personally, I wanted her to be a guide because people are not that familiar with Dubai. They’re familiar with Dubai now—this kind of Disneyland, über-Vegas, or whatever you want to call it. But that was not the Dubai I knew. I found out that not a lot of people were familiar with that Dubai. I wanted [Riya] to be this person made from that place. She’s kind of a hustler; she’s shouldering a big responsibility, but she feels very deeply. At the same time, she’s in her mid-twenties, you know? It’s a time of self-doubt and fears. You’ve just left home and you are having intense relationships, whether romantic or otherwise. You’re at that certain time of your life where you know you have to do the right thing, but you don’t always do the right thing. So my thought was, how could I write this character who is kind of in a double-bind in that what she needs to do for her family doesn’t necessarily reconcile with her wishes for herself? Maybe she’s not a very self-reflective person, but she is self-aware. She has no time for your bullshit. That also comes from the situation she is in. Then of course, there’s the war, and that gives her the chance to make choices she didn’t feel she had before or get the wherewithal to make before.

DC: What inspired you to write about 1990s Dubai now? How would you connect that moment in history—if you would—to “the events” today?

TM: It kind of slowly happened, thinking about whether to write about Dubai. I lived there around that time. My family lived there. My parents were there during the war, and in the lead-up to it, I was still going to school and going back and forth. I did work there for a few years for a couple of different tour operators. But when I came to the U.S. in the mid-’90s, I would say Dubai and people would just glaze over. They had no idea where Dubai was. And then a couple of events happened. 9/11 happened. Some of the terrorists came through [Dubai] and had a lot of funding through there. There was another scandal with the Dubai ports. Then everyone started hearing about all this construction happening, about these islands being built in the shape of palm trees and the world’s tallest building and the black diamond ski slope in the middle of this desert. Everyone started paying attention to Dubai, and they had an impression of this “money-can-do-anything” kind of place. It almost subverts nature over there. Literally, they’re subverting nature. But I thought, “Oh, well, no one knows about the Dubai that I knew.” That Dubai doesn’t really exist anymore. It’s been superseded by this whole new city. I just knew this feisty little place where there were these people from all over the world, and they were just there to make money. You couldn’t have citizenship so they were making money for a future that was very uncertain. They didn’t know where they were going to go, but they needed to make money. Everyone had this certain bravado that was very poignant and compelling. It was full of all these interesting characters, it had very loosey-goosey rules, which all changed after 9/11. But people could come and go; there were all these arms traffickers based there. You would run into people like that all the time. It lent itself to this landscape that you can set all these characters in.

Then, of course, the war was very interesting because the war itself only lasted like a month. It was so short, but the whole lead-up to it was so long and so tense. No one knew what was happening. Will Saddam Hussein bomb us? He had Scud missiles, he had biological weapons. What was going to happen? If you’re talking about how it connects, it’s that life has always been a struggle. There always seems to be a war in some place.

I’m going to see this Ukrainian author [Andrey Kurkov] who’s written a book called Diary of an Invasion. He’s like, ‘We knew the war was going to start and yet we were dealing with the coronavirus.’ There’s this huge thing happening at the back, but you’re going on with your regular life. It was the same then—the war was like a continuous scream in the background, it was impending, it was coming, yet you were going along with your life. You still had bills to pay, like we all did during the pandemic. People rise to the challenge and they manage to find happiness and joy in small situations. I feel that relevance still holds.

DC: There’s a lot of dark humor in the book, especially in reference to characters’ lack of control. Some of my favorite lines were, when Grace says, “Shut up and be serious,” and [another character] says, “Why? We’re screwed either way.” Or the scene when Mrs. Wehner is telling Riya that she alone is responsible for her own happiness and Riya says, “It’d be more helpful if Mrs. Wehner gave her advice to Saddam Hussein. There was a man who needed to seek contentment within himself.” How did you manage to perfect that tone?

TM: This is kind of a war novel, but it’s not a war novel in the typical sense. No one is being bombed; people are not being dragged off the roads and executed. Yet there is an absurdity to violence. When someone decides to commit violence, there’s some absurdity in that, whether it’s a small act or a big act. I kept that in mind while writing these characters, because they were in an absurd situation. People were still coming [to Dubai] for vacation. They still were drinking cocktails and lying by the beach.

Money makes so much delineation between people and also gives people power over you.

A country away, U.S. forces were amassing, taking over huge buildings and moving in, and there were all these huge ships in our ports. These poor young boys who probably had only heard about war, like Vietnam, from their grandparents and probably never thought they would go to war were suddenly in this strange land where the laws were so weird—can I talk to someone, can I not talk to someone? I can’t drink here? Putting all these elements together was so comical in a way that I couldn’t help but bring [humor] in.

I also did see the two people who were controlling these events, George Bush and Saddam Hussein. Bush was kind of known as a wimp because he was coming after Reagan, so he wanted to fight that perception. Saddam Hussein was very capricious and had this odd mixture being very rash and calculated at the same time. You never knew what he was going to do next.

DC: Riya seems to have a very clear sense of familial duty; she’s always sending money back to her family. But she’s pretty lax about the social strictures of living in Dubai at that time. How do you see her moral compass? What does it point to?

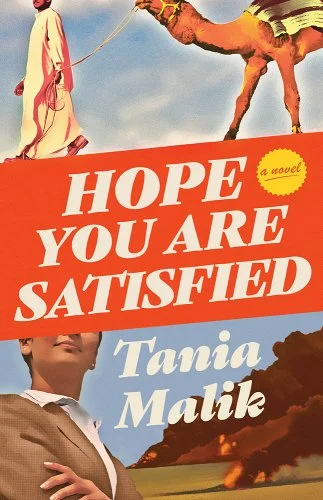

TM: I think [Riya] is self-aware, even though she’s not very reflective about what she does. She does know when something feels wrong, and maybe she still has to do it because that’s just her life. She doesn’t always have a choice. I also wanted to take this whole thing about “luck”—like, luck is something you make. It’s such an American thing, rather than a choice. It’s very arrogant. That’s something I understood when I moved to the U.S., whereas in the East, it’s “fate” that’s paramount. [Riya] wants to come to the States, which many people find very hard to articulate—why do they want to come? It’s just that it’s been sold to everyone as this whole cliché of opportunity, and that is correct. Whether that affects her moral compass or not, I think it goes with each situation. So I think she is ready to do things if it can get her what she wants—to a certain extent. I don’t think she will commit certain acts of violence. In that way Dubai was also very much a place of double standards. The tourists could drink, and we could drink in hotels, but the Muslims couldn’t drink. Muslims can’t buy pork. There’s a separate place in the grocery store for pork products that only fully non-Muslims can go in. It was very much a place of dichotomy. That’s why I like the cover, because I think it shows the “exoticness” of that Arabia that we were selling everyone, and then on top of that the violent landscape.

DC: Why did you decide to have Riya pin her hopes on the U.S.? Would you describe that as just this vision, or version, of the U.S. that’s been sold to people overseas?

if you were from the East, you were called a ‘guest worker’ or a ‘laborer’; if you were from the West you were called an ‘expat.’

TM: I think so. When I was [in Dubai], a lot of people didn’t want to go back home, because home would be the same opportunities. India is much more developed now; at that time, it hadn’t had this big economic boom and all these changes. So the only option was to go West. Some people did go to the U.K., some people did go to Australia, but Canada was number one because it was so easy. That was where they could build a future. Dubai was very much a transit point. You couldn’t get citizenship. That’s changed, too, now some people can. But basically, you earned your money and you left. The U.S. was absolutely this land of opportunity. There was still this idea that you can do what you want; it didn’t matter where you came from. It’s hard to come to the U.S. legally. The U.S. immigration code is, I think, only second in complexity to the tax code. But because this idea was sold to [people], they were ready to jump through those hoops to get here.

DC: Class disparity plays a huge part in what the characters are or aren’t able to do. Riya can’t leave Dubai on her own because her passport is in a safe at her workplace. And I was interested in the difference between Riya’s encounters with the wealthy tourists and her encounters with wealthy residents of Dubai, like her big boss, César. It felt like a different kind of disparity.

TM: Money makes so much delineation between people and also gives people power over you, especially in that situation where they hold your freedom in their hand, like that passport can help you go somewhere. It is a way of control. I also think, being a woman in that situation, there is this attitude among men—it wouldn’t even occur to [Riya’s bosses] that she would question them. They would just expect her to fall into place. If she had questions, she would keep them to herself; she wouldn’t mess up; she would tow the line.

People who had money didn’t have to have their passport. It was only the low-level staff. If you were the C.E.O. and you were a foreigner, your passport was with you. I think also there was a little bit of racism—if you were from the East, you were called a “guest worker” or a “laborer”; if you were from the West you were called an “expat.” That’s why I thought characters like Hannah, or the German guys, were interesting because they straddled both. They were there because they needed money, but they did have a little bit of leeway because of the color of their skin. They were a little bolder in how they approached everything. Money brings power, and that power skews in a very different way in a place like Dubai where there are all these rules and regulations that are particular to the place. There’s no other place in the Middle East that they’ll take your passport and keep it as a protection against you doing anything wrong. Even the tourists who came in had to be sponsored, so the hotels would sponsor them, or the travel agents would sponsor them. Everyone had to be sponsored at that time to get to the country. That is the kind of control that we can’t even imagine over here.