Interviews

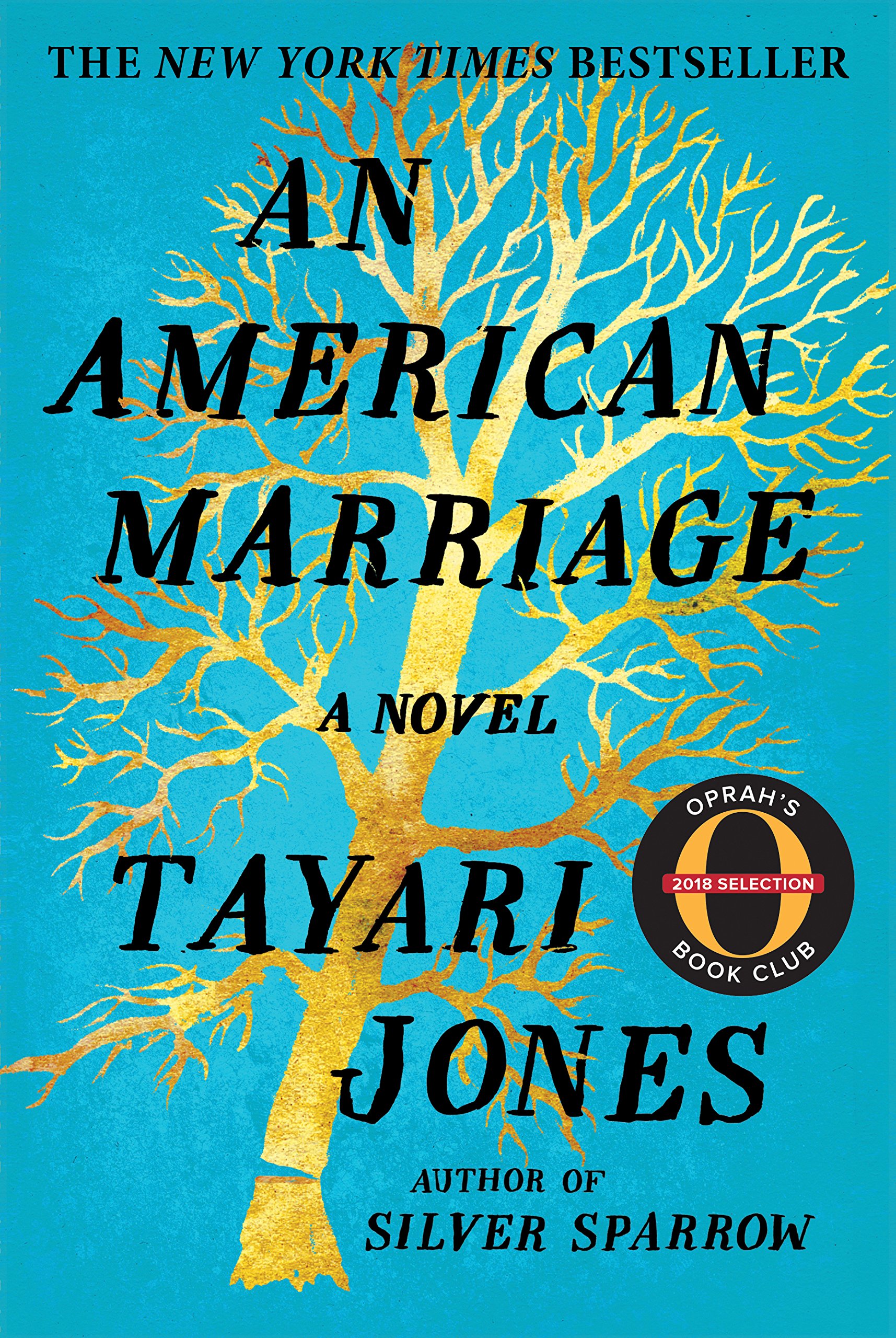

Tayari Jones Writes About People with Problems, Not Problems with People

Her latest, ‘An American Marriage,’ is about race and incarceration—but mostly it’s about three people facing their feelings

Tayari Jones’ first novel Leaving Atlanta didn’t only introduce me to a new favorite author; it also taught me a lot from a craft standpoint. The book follows the story of three children during a time of great fear, capturing the heightened awareness of a threat and also the reality that life doesn’t end when tragedy strikes. As a reader, I was emotionally gutted. Jones’ attention to people and situations as well as a very expert knowledge on story construction kept pushing me to probe deeper as a writer.

I’ve read every novel Jones has published since Leaving Atlanta, and while I’m still a huge fan of her first novel, the material she tackles and the people she creates get better with each new book — from The Untelling to Silver Sparrow to her latest, An American Marriage. American Marriage poses a lot of discussion in terms of race, gender, and societal expectations. Feelings may very well run the gamut as you hear from Celestial, Roy, and Andre — a love triangle that has resonances far beyond mere romance. Celestial and Roy are a young married couple, still almost newlyweds when Roy is falsely accused and later incarcerated. While the world for Roy stands still behind bars, it continues to spin for Celestial. Celestial’s role as wife is an unbearable weight forcing her to consider the kind of love she and Roy do have. When Roy is released, the tensions between him, Celestial, and Andre (Celestial’s childhood friend and new beau) come to a head.

I spoke to Tayari about dealing with social issues in An American Marriage, reader reactions to the book, and how expectation, be it of genre or character, challenges readers to appreciate the larger story and its delivery.

Jennifer Baker: While An American Marriage centers on the core characters’ relationships, it’s not necessarily a social justice-y novel that focuses on the issues of incarceration.

Tayari Jones: Social justice is not a character. Every person who is impacted by social issues is also busy living a life. When people say, “it’s about them and not about the issue,” I feel like every good novel is about the people.

Just like in my first novel on the Atlanta child murders, I was not so much interested in whodunit. I was interested in to whom was it done. What it was like for people growing up in Atlanta in that time. How did it affect their coming of age? In this novel I’m really interested in the way Celestial and Roy’s young marriage has been impacted by this major racial injustice, but it doesn’t change the fact that it’s a marriage. And how the marriage works or fails depends on the two people.

Every person who is impacted by social issues is also busy living a life.

JB: But you don’t ignore the issue.

TJ: No, the issue is part of their lives. My mentor used to tell me, “Write about people and their problems. Don’t write about problems and their people.” So Celestial and Roy are real people with a problem.

JB: And you also bring Andre into it. It’s about the marriage, but Andre is a factor that we can’t ignore.

TJ: It’s a love triangle. I put Andre’s voice in because there were things happening to Andre. Also I just like the guy. But I needed to have two male voices because I didn’t like the way it started to feel like Roy was standing in for “the Black man.”

Just putting Andre in there — giving more than one voice a Black male experience — it took a lot of pressure off of each of them not to have to function symbolically. It allowed them each to function more as individuals.

JB: Another thing that comes up is the dictation of behavior and the expectation from family. Celestial and Andre deal with that a lot.

TJ: I think they all do. It’s just that Celestial and Andre are not doing what people want. And Roy, for example, all his life everyone who has met him has thrown him a parade. His whole life. All his life everyone has been so excited about him because I think he represents Black male progress in a way that people like. I think he doesn’t realize the extent to which he is influenced by societal and familial…. For him he wouldn’t describe it as pressure, I think he’d describe it as influence. But he has just been on the right side of what people have always wanted for him his whole life. Whereas Celestial is a woman trying to make her own way, she is constantly butting up against people’s expectations that is not affirming.

46 Books By Women of Color to Read in 2018

JB: Why did you decide to make Celestial an artist? Because that comes into play for their marriage too.

TJ: To make Celestial an artist was a hard decision for me. I decided to make her an artist and Roy would be her subject. And if you think about it Roy is delighted with her art when he feels it celebrates him in an uncomplicated way. Like when she’s making dolls that look like him as a baby. He loves that. But when she makes a doll that reflects his situation in prison and she receives accolades for it, it makes him uncomfortable.

JB: But she also doesn’t talk about where it comes from.

TJ: She doesn’t talk about him. She talks about how she’s interested in mass incarceration and wrongful imprisonment. But she doesn’t say his name. So even though he’s inspired the art, it doesn’t reflect him in the way he wants to be reflected. But then he says something interesting to her: “I’m gonna tell you, no amount of art has ever gotten anyone out of prison,” when she says she wants to raise awareness about the issue. And as an artist myself I thought there are limits to what art can accomplish. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t make art. It doesn’t mean art isn’t valuable. But when Roy says that to her, it humbled me as a writer.

JB: That’s another thing Celestial has to argue for as well. She keeps asking Roy “Can’t you understand?”

TJ: This is her life’s work. This is the thing I’ve been working toward all my life. But the fact of incarceration makes anything she enjoys seem almost criminal. And then you think about that metaphorically as an African American narrative. For any of our pleasures when our brethren and sistren are in such distress: Is there a built-in guilt factor with our own mobility?

JB: Do you think readers have a hard time grasping at that because of those predetermined notions of protecting men, as in ‘women do this to protect men’? Just like Celestial’s father seems to be that representative who wants to protect Roy. He keeps leaning on the big societal issues, that he was just at the wrong time and wrong place…

TJ: “…and the least you can do is to preserve yourself in amber for him.” It’s as though people can only think of her support system in one way, which is romantically/sexually. And she says she is not going to deny her sexuality, then it’s like you’re horrible, you’re abandoning him. There’s only one way she can be supportive? And I kind of think that’s unfair to her.

JB: I’m a woman who reacted to that and thought/felt certain way. I wanna say felt because maybe that’s where it’s coming from? People are feeling a certain way?

TJ: Yes, and I think there’s also a challenge in expectation of genre. Because when you say it’s a novel involving wrongful incarceration you assume the novel is an issue novel about a fight to freedom. You have to know how the characters are positioned. So when a novel kind of challenges expectation of genre it is frustrating to the reader on some level. I think the reader has to power through to read something different from what she was expecting.

I think the reader has to power through to read something different from what she was expecting.

JB: And how was that for you to write and feel, in the end, “This is exactly where this needs to be”?

TJ: The last 50 pages or so were really hard for me because I had to figure how all three of these people who I feel are very sincere in their intentions — how could they all walk away from this sadder but wiser? I felt like they were my 3 children and I had to make sure they all get a gift under the tree. And it has to be believable and it has to be real. So my question was: How can we move forward into the future together? And so I had to figure it out. It was a hard question.

’Cause at first I was saying “This is a love triangle, someone’s gotta lose.” Then I realized that was the wrong way to think about it.

JB: Because losing meant something else?

TJ: It made getting the girl or not getting the girl the measure of the experience. And as Andre says Celestial is not something like a wallet. The expectation of genre means if you say something is a love triangle it means who gets the girl? Who gets the guy? And I had to take that genre expectation out of my own head. And the question is: How can they each move forward whole?

That genre expectation is very, very difficult. If a story has a detective in it, you think it’s a detective story. So if you have a novel with a detective and they don’t solve the crime at the end you’d be very frustrated because of your expectation of genre. It can be a fine book with an emotional ending, but if you don’t know whodunit you feel like the book didn’t honor “the contract with the reader.” And I realized that when Roy was wrongfully incarcerated I was setting a certain contract. When I decided it was a love triangle I was making another contract. So I had to renegotiate both those contracts in order to write this book.

If a story has a detective in it, you think it’s a detective story. So if you have a novel with a detective and they don’t solve the crime at the end you’d be very frustrated because of your expectation of genre.

JB: I think people are also consistently focusing on the incarceration.

TJ: I think that’s absolutely true. And incarceration is such a gendered situation. I think they’re thinking that because it begins with Roy’s voice, because it’s read as a book about a man they don’t see that it’s a book about gender even though men have a gender as well.

So much of this is about masculinity. It’s about fatherhood. I feel that’s what makes Roy able to go on with life is that he has to reconfigure his understanding of self and masculinity. He thinks that to be a free man is to exert dominance over his household. But what he learns to be a free human being means that you’re a person who can exercise empathy. That being empathetic is not a luxury. That it is a core tenet of your humanity. And with that you are a free. That’s what he has to learn. So he has to set down these antiquated, Odysseus ideas for what it means to have a triumphant homecoming, what it is to be a free person.