Reading Lists

The 12 Worst Workplaces in Contemporary Literature

More reasons to live in your mom’s basement instead of getting a day job

From office drones occupying bland white cubicles of repressed misery in Corporate America to unwanted but necessary guest workers toiling in the hot sands of Abu Dhabi, these 12 contemporary books skewer corporate culture and reveal the inevitable result of a capitalistic society that views workers as anonymous, replaceable cogs in a never-ending pursuit of profit.

This Could Hurt by Jillian Medoff

This Could Hurt opens with a series of employee terminations (if the cover or title isn’t telling enough) in the wake of the economic recession. HR executive Rosa Guerrero is tasked with the paradoxical job of guiding her employees while firing more and more people to maintain profitability. Her department has shrank from twenty-two to sixteen to thirteen and now, eleven with “despair (setting) in.” Each chapter features the viewpoint of different characters, retelling the same meetings and conversations from their perspective. The motley crew of middle managers are self-absorbed, manipulative, and dysfunctional but their all-too-human flaws are redeemed by their fierce loyalty to Rosa and the lengths they go to to protect her when she experiences a stroke that leads to her memory and behavior deteriorating.

Temporary People by Deepak Unnikrishan

‘Temporary People is a work of fiction set in the UAE, where I was raised and where foreign nationals constitute over 80 percent of the population. It is a nation built by people who are eventually required to leave,” prefaces the author. In these 28 interlinked stories and poems, Unnikrishnan combines Malayalam, Arabic, and English to encapsulate the dissonance of these displaced guest workers straddled between two countries and breaking their backs for a country that they can never call home. The displacement and dehumanization of these perpetual foreigners manifests as metamorphoses: a migrant moonlights as a mid-sized hotel, a runaway shape-shifts into a suitcase and a sultan grow “ideal” workers with a twelve-year shelf life from pods. One chapters contains only a list of occupations “Tailor. Hooker. Horse Looker. Maid.” and ends with “Cog. Cog? Cog.” With anti-migrant sentiment at an all time high, Temporary People is a timely and necessary exploration of how “temporary status affects psyches, families, memories, fables, and language(s).”

The Beautiful Bureaucrat by Helen Phillips

Young married couple Josephine and Joseph are fresh arrivals to the city bouncing from one grimy sublet to the next, hoping to finding work and better their lives. Josephine’s life take a turn for the bizarre after she is hired by a faceless, androgynous person. She spends her work days in a tiny windowless office enclosed by revoltingly pink walls, entering a never-ending series of incomprehensible numbers into “The Database.” Her only encounters in the company are with her nameless boss, “The Person with Bad Breath,” and a Barbie doll-like bureaucrat named Trishiffany (“My parents couldn’t pick between Trisha and Tiffany”). The files starts piling up, but no one will explain to Josephine what the company does or what the numbers mean. Josephine’s misgivings turn into dread when her husband disappears more and more frequently with no explanation of his whereabouts and “delivery failed” notices affixed with her name start appearing on her apartment door even though no one has her new address. Author Elliot Holt wrote: “The Beautiful Bureaucrat demands that you keep turning its pages to find out what happens.”

Radio Iris by Anne-Marie Kinney

Iris Finch is an unassuming receptionist working at a nondescript company. She isn’t sure what the company does or why her colleagues suddenly disappear, leaving abandoned offices filled with junk in their wake. Her boss, already a rare presence, starts vanishing for long stretches of time only to turn up at the office briefly to hide envelopes under floorboards. The company phone eventually stops ringing, leaving her with nothing to do but she finds comfort in the routine of work. Her life has some illusion of purpose “as long as she had a place to go every morning.” In the suite next door, a mysterious man starts living in the office space and showering in the men’s bathroom. With little going on in her personal life, Iris arrives for work earlier and earlier each day to spy on the strange tenant using a hole she has drilled into the adjacent wall. She writes to him with a plaintive vulnerability: “Please don’t go yet. My name is Iris. I want to talk to you.” Radio Iris is a story of a lonely young woman, emotionally numb in a meaningless job, yearning for connection.

Kevin Kramer Starts on Monday by Debbie Graber

Cate Dicharry writes that Kevin Kramer Starts on Monday is a “ruthless, hilarious critique of corporate decision-making, and nonsensical professional language and culture — all punctuated with desktop defecation, a defunct band named the “Butt Gerbils,” and trenchant, playful humor.” The short story collection features a con-artist who ruins his own company (simply because he can), an abandoned car found in the employee parking lot with a detached ponytail on the hood and a company-wide newsletter affirming the sci-fi like mass disappearance of staffers. Graber artfully mines the mundanity of corporate culture into bizarre and hilarious tales of the 9 to 5 purgatory we call work.

The Circle by Dave Eggers

“SECRETS ARE LIES. CARING IS SHARING. PRIVACY IS THEFT.” These are the mantras of The Circle, the world’s most powerful internet conglomerate that aggregates the digital footprints (social media, banking, emails etc) of its users into a unified online identity. The novel follows Mae, an idealistic and enthusiastic new employee as she rises in the cult-like company and goes “transparent,” broadcasting her life live to her “watchers” 24/7 with tragic consequences. “A fascinating Orwellian riff on Silicon Valley,” as Manuel Betancourt wrote in his review, The Circle imagines a sinister world where social media has killed privacy and users are coerced into constant surveillance for the sake of “transparency.”

Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh

Eileen is a bitter, self-loathing young woman working as a secretary for minimum wage at a grim correctional facility for delinquent boys in a cold, bleak New England town. She spends her nights supplying booze to her alcoholic, dementia-ridden father while her work days consist of filing away reports of horrific crimes committed by the adolescent convicts, secretly nursing sympathy for them. Her grim existence is made bearable with lustful fantasies of Randy, the prison guard, and daydreams of escaping to a new life in New York City. When the Rebecca Saint John, the new counselor, shows up at the juvenile center, Eileen falls into a friendship that takes a dark, lurid turn and changes her life forever.

Lightning Rods by Helen DeWitt

Joe is a failed door-to-door salesman of encyclopedias and vacuum cleaners. who spends his days fantasizing about disembodied sex. One day, he has a Eureka moment: “Women were being molested in the workplace solely because their colleagues did not have a legitimate outlet for urges they could not control.” Joe commodifies his perverse fantasies into a successful corporate service: “lightning rods” — female office workers whose lower halves provide anonymous bathroom sex — that alleviate male desires, eliminate sexual harassment in the workplace and cut the expense of lawsuits. After all, a happy office is a productive office and productivity means more money (real words I once heard at a presentation hawking employee monitoring toolkits). Dewitt satires the robotic corporate culture that treats their employees as replaceable, anonymous drones in the obsessive pursuit for efficiency.

The Pale King by David Foster Wallace

David Foster Wallace’s fictionalized memoir literalizes the deadly monotony of pushing paper and crunching numbers from 9–5 in an I.R.S office in the Midwest. A whole chapter is devoted to accountants silently flipping page after page of tax returns. Filled with esoteric financial jargon and tax codes, the most excitement to be found is the clash between the older generation of I.R.S employees, motivated by sanctimonious civic duty versus their more modern colleagues who see their bottom line as maximizing profits. The workers slog away at their mindless and unfulfilling work to “cover the monthly nut,” “thrashing in the nets” of societal expectations while the ever-present threat of being replaced by computers becomes increasingly real. Published posthumously, this metafictional novel questions the meaning of life in a corporate America populated by countless identical workers rigidly adhering to pointless bureaucracy.

Personal Days by Ed Park

“Most of us spend our days at a desk in one of the two archipelagoes of cubicle clusters. The desks have not been at capacity for over a year now,” begins Park’s novel about a company in the process of downsizing. With little to do, the unnamed narrator and his colleagues spend their days theorizing over who will be the next victim of “the Firings”—after the termination of employees with J names, the Ls in the office agonize over their impending doom. Broken up into three Microsoft Word-themed chapters titled “Can’t Undo,” “Replace All” and “Revert to Saved,” Personal Days features characters immediately recognizable by anyone who has spent time in a cubicle: Pru, a fresh-out-of-grad-school spreadsheet drone, Laars, a wall-punching neurotic teetering on the verge on a breakdown and Jack II, administrator of unwelcomed backrubs known in the office as jackrubs. Rife with office lingo and corporate speak, Personal Days serves as a darkly comic guidebook for navigating the cloud of uncertainty that accompanies the looming demise of a company.

Then We Came to the End by Joshua Ferris

“The fact that we spend most of our lives at work, that interests me,” says Hank Neary, a copywriter in a white-collar ad agency. Ferris’s satire of the American workplace takes place at the end of the 1990s dotcom boom when work is scarce, redundancies are imminent, and tensions are rising. In the middle of this downturn, the struggling agency accepts a mysterious client’s request to create an ad that will “make cancer patients laugh”—an assignment made doubly cruel as rumors spread that Lynn Mason, the supervisor, has breast cancer. This darkly comic portrayal of office culture is populated by eccentric characters (there’s a single, pregnant, and devoutly Catholic woman and a stubborn copywriter who keeps showing up for work despite being fired) and chronicles their increasingly desperate attempts to survive the axe.

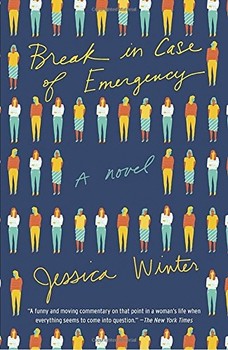

Break in Case of Emergency by Jessica Winter

Jen is a thirty-something former painter struggling with unemployment during the economic downturn. She finds a job at the Leora Infinitis Foundation, a charitable foundation/vanity project founded by a Gwyneth Paltrow-esque celebrity philanthropist who purrs meaningless platitudes (“You are beautiful inside and out. That is the message of LIFt”) and answers her own self-affirming contradictions ( “How do I put my children first and put the children of the developing world first, too. My answer is yes.”). The foundation purports to empower women yet its employees passive-aggressively sabotage one another, waste time devising acronyms for unrealized programs, and ingratiate themselves to their egoistical boss. Trapped in a meaningless job writing memos no one ever reads and struggling to conceive a “hypothetical tiny future boarder,” Jen is crippled by self doubt and constantly compares herself to her two closest friends — Meg, an affluent attorney with a beautiful family, and Pam, a committed artist. When her personal life and professional career converge violently at an art exhibition, Jen is left reckoning with some hard truths that eventually gives her life meaning.