Books & Culture

The 13 Most Terrifying Apocalypses in Literature

Author Cat Sparks on the many ways the world might end, and which books you can read for a glimpse of the coming cataclysm

Is there any such thing as a pleasant apocalypse? Probably not, although the cozy catastrophes of post-World War II seem to suggest that a global cataclysm might do the world a favor by wiping clean the slate, enabling the “right sort” of people to reclaim it.

There’s no shortage of dystopian and post-apocalyptic literature out there — over 3,000 novels deal with nuclear aftermath alone. In my debut novel, Lotus Blue (Talos, 2017), I envisioned a future ruined through corporate greed, careless governance and unregulated technological experimentation, a logical extrapolation of climate change denialism coupled with military applications of artificial intelligence and autonomous weapons systems. Dune was the novel that initially inspired me, but what I ended up with is more along the lines of Fury Road.

End-of-the-world scenarios leave us wondering who or what we might become, and if our species might end up getting precisely what it deserves.

From Capitalism to Underpopulation, here are the top 13 horrible apocalypses that make people question their faith in humankind.

Capitalism: Feed by M. T. Anderson

Protagonist Titus isn’t a bad guy, really, he simply possesses no mechanisms for thinking for himself. This YA novel interbreeds neoliberal capitalist consumerism and social media, pushing them to their logical conclusions and farthest extremes — what happens when all the shouty infomercial advertainment chitter chatter lives permanently inside our skulls? The answer is, of course, varying degrees of nothing good. The apocalypse will be digital…

Cannibalism: The Road by Cormac McCarthy

A man and his young son travel the frozen roads of North America, heading south towards the ocean and whatever hope it might provide. Why the father, as an expression of his undeniable love, doesn’t put a bullet in the boy’s head early on to spare him from the lingering horrors of a barren, resource depleted ash and dust encrusted wasteland replete with murderous, marauding cannibal gangs, we will never know. All the love left in this world will never be enough. Despite the many rough-road tales to come before it, The Road still manages to emotionally bludgeon readers with a couple of specific scenes. If you’ve read the book or seen the movie, you’ll know.

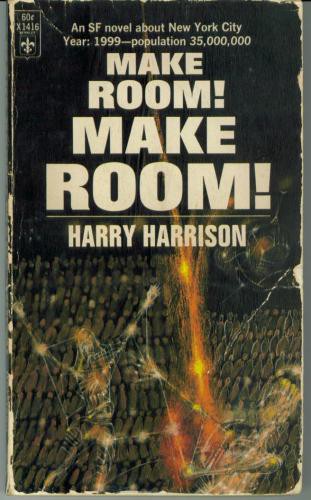

Overpopulation: Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison

Human overpopulation was one of the chief concerns of science fiction’s ecocatastrophe writers of the 60s and 70s. Even if you haven’t seen the film, you’ve likely heard the catchphrase: Soylent Green is people! The novel contains no mention whatsoever of cannibalism via humans recycled as luridly colored protein bars but it is more stifling and relentlessly claustrophobic than the movie, with its utter lack of spectacle or punch line. Just more and more people scrambling for crumbs, squeezed into less and less space.

Underpopulation: The Children of Men by P.D. James

The novel interrogates the shapelessness of existence once all human fertility has ceased and cities increasingly become peaceful repositories of the docile aging. Despite resources aplenty, the Warden of Britain encourages atrocities against foreign workers, the feeble aged and troublemakers in general, running the country as his own private fiefdom.

Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006 movie is arguably more visceral, chilling and sophisticated than the book, focusing on acts of government brutality rather than the protagonist’s inner turmoil — it is impossible not to draw parallels to harsh contemporary world treatment of refugees. If Children of Men is a cautionary tale, then we clearly missed the message.

Biopunk: Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood

Wrapped in a decaying bedsheet, Jimmy, aka Snowman (as in, abominable), picks through the ruins of society, worshipped by genetically engineered Crakers, a designer humanoid species with lurid blue genitals, no smarter than they need to be. They’re set to inherit a nightmarish anti-Eden crawling with monstrous biological blends such as rakunks, pigoons, wolvogs, snats and ChickieNobs, animals recklessly engineered for their commercial usefulness back before a deliberate pandemic wiped out most of the human race. Which pretty much had it coming.

Ecological: The Death of Grass by John Christopher

Many kids loved Christopher’s Tripods novels: The White Mountains, The City of Gold and Lead, and The Pool of Fire, where the kids get to fight back against alien invaders. Written for adults a decade earlier, The Death of Grass portrays self-centered human survivalism at its most despicable: a convoy of London refugees enacting across two days an analogy for the fall of civilization, committing whatever violent acts they deem necessary to reach John’s brother’s farm, deciding their own survival is all that matters.

Climate Change: The New Atlantis by Ursula le Guin

Belle’s husband Simon, newly released from labor camp, meets in secret with their scientist cohorts to discuss their solar battery that could solve the world’s energy crisis. They know it’s hopeless but they continue anyway, because that’s the essence of who they are. The most depressing element of this story is not its horrendous, unholy blend of neoliberal capitalism and totalitarian collectivism governance, but the fact of how casually polar ice melt, rising oceans and other realities of climate change are mentioned in passing as a backdrop to the narrative. This story was published in 1975 by one of speculative fiction’s greatest voices, and yet, here we are today.

Available to read free at Lightspeed.

Fundamentalism: The Orchid Nursery by Louise Katz

Mica and Pearl are girlies, raised and schooled in the virtues of CHOM: compliance, humility, obedience and modesty; palliation vehicles for the desires of Men. The luckiest among them will be selected as womanidols, living out their allotted time in perpetual and glorious sacrifice in the Orchid Nursery. You really don’t want to know what that entails. It is not the first SF novel to tackle the brutalism of enforced female purity, but the one that leaves the worst taste in your mouth. Religious fundamentalist sexism taken to its farthest and most hideous extreme.

Post Peak Oil: The Drowned Cities by Paolo Bacigalupi

Young orphaned Mahlia assists kind-hearted Dr. Mahfouz, despite having had her right hand hacked off by Army of God soldiers. The jungle infested shattered ruins of Washington DC crawl with squabbling warlord factions, coywolvs, panthers and monstrous half-men bred from a DNA cocktail of tiger, dog and hyena. When Mahlia and fellow orphan Mouse discover a killer Augment named Tool half dead in a swamp, an unlikely partnership is formed.

One of those YA titles that seems too relentlessly horrible for its marketing category. Still, it’s a damn good read.

Disability: The Day of the Triffids by John Wyndham

Almost the entire population of the world is rendered blind overnight after witnessing a pyrotechnic meteor display, the result of an accidental weapons malfunction in orbit… If that weren’t bad enough, aggressive monster plants, triffids, the outcome of ingenious biological meddlings, roam the streets, attacking helpless humans.

The triffids are by no means the scariest aspect of this story, they are nothing compared to the abject horror of an entire world fallen blind and helpless. The few remaining sighted have the upper hand and the world is now their playground.

Demagogue: Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler

It’s 2032 — a variety of wars are raging all around the climate change afflicted world, but the members of Acorn, led by Lauren Oya Olamina, have built a relatively secure, workable community. They follow Earthseed, a faith developed by Lauren on the road. But when far Christian right Senator Andrew Steele Jarret is elected as POTUS, promising to ‘Make America Great Again’ (sound familiar?), Acorn is destroyed and its people slave-collared with devices that deliver painful punishment at the whim of their controllers.

Parable gives the reader the experience via the power of literature of what it might actually feel like to be a slave. In a nutshell: furious and powerless.

Nuclear: A Boy and His Dog by Harlan Ellison

Vic is a solo, part of Our Gang, who run the local Metropole cinema, where men sit around jerking off to ultraviolence and beaverpicks in the ruined aftermath of the Third World War, which killed off most of the girls. Rovergangs run everything that matters aboveground: from power plant to reservoir to marijuana gardens. The middle-classers escaped to enclaves underground. The smart ones stay down there.

Vic’s best friend is a talking dog called Blood, who, as well as having taught Vic to read and write and correcting his gangland grammar, uses his enhanced psychic abilities to sniff out women for Vic to rape. Utterly charming. Especially the end.

And the award for most horrible apocalypse goes to…

Aliens: The Genocides by Thomas M Disch

The Earth has become overrun with fast-growing alien plants, 600 feet tall with leaves the size of billboards. As arable farmland is consumed, the human population dwindles, from famine, violence or spherical alien incendiary devices, which eventually force survivors underground into the roots of the alien plants. Protagonist Buddy isn’t much of a hero. His pregnant wife is forced to survive on the food scraps he leaves in the pot.

Readers will find themselves rooting for the plants way before the humans start burrowing, because these nasty brutish stragglers are way past being worth saving. The cannibalism might be forgivable, but not their fierce, unreasoning Calvinist cruelty.

Bonus story: Disch also penned “Casablanca,” hands down the most disturbing short story about tourism gone wrong ever written.