Lit Mags

The Apartments of Strangers

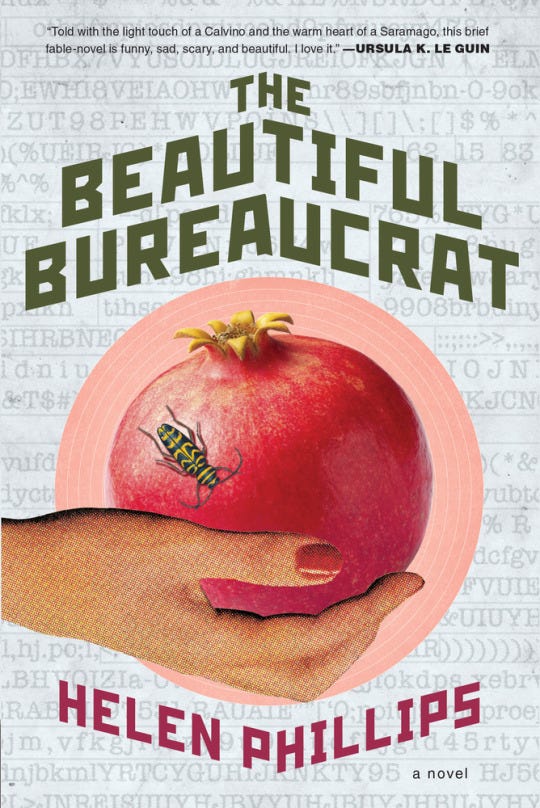

An excerpt from THE BEAUTIFUL BUREAUCRAT by Helen Phillips, recommended by Elliott Holt

AN INTRODUCTION BY ELLIOTT HOLT

I told Helen Phillips that her novel, The Beautiful Bureaucrat, is an “existential thriller.” That might sound like an oxymoron: after all, existential literature is known for its lack of action. Existential texts are usually about being stuck: waiting for Godot, or trying to escape an insect’s body. The Beautiful Bureaucrat demands that you keep turning its pages to find out what happens. And yet Phillips’s book — absurd, uncanny, tinged with dread — owes more to Beckett and Kafka than to Lee Child or Stephen King.

The Beautiful Bureaucrat concerns a young married couple, Josephine and Joseph, newly arrived in a city reminiscent of New York. After being evicted from their apartment, they move from short-term sublet to sublet. When I read this excerpt, I remembered the summer, a few years ago, when Helen Phillips and her husband rented my Brooklyn apartment for a month. To sublet (or rent from Airbnb) is to step into someone else’s life; you stand beneath another person’s shower stream and assume, temporarily, another identity. It’s a precarious, disorienting existence.

For Josephine, that disorientation is compounded by her job. After being hired by a “faceless” person of indeterminate gender, she spends her days in a windowless room, entering data that no one will explain. She is a cog in a machine she can’t understand. Meanwhile, her husband disappears to his own enigmatic job every day. As his absences become more frequent — and the psychic distance grows between them — Josephine is determined to learn the truth about the strange company where she works.

The Beautiful Bureaucrat is as much about the mysteries of marriage as those of human existence. Phillips has created an abstract world, but the see-saw of Josephine and Joseph’s relationship is realistic. Their essential connection gives meaning to the absurd landscape. And that connection is built on language: they construct their own world with words. Everything around them is unsteady (even their table is “wobbly”), so it is language they depend on. In this excerpt, we see their empowering wordplay and then their jarring loss of connection. How terrifying it is for Josephine when syllables distort; when Joseph’s voice over a bad phone line becomes nothing but “fragments, blips and fuzz.” The fragmentation of language, and its replacement in this section by animalistic coupling, reflects the shaky state of their union.

Elliott Holt

Author of You Are One of Them

The Apartments of Strangers

Helen Phillips

Share article

An excerpt from The Beautiful Bureaucrat by Helen Phillips, recommended by Elliott Holt

Joseph was sitting on their bed. Their bed was out on the sidewalk in front of their building, surrounded by everything they owned, all the objects they had brought with them from the hinterland. It wasn’t much, but it was theirs: the bookshelf, the wobbly table, the plant, the suitcases, the folding chairs.

She ran down the block toward him, forgetting all the celebratory plans she had made on the train coming home from the job interview.

“We’re evicted,” he said neutrally as soon as she was standing before him, breathing hard.

She kept her eyes on their stalwart jade plant as he explained how, moments after he’d returned from work, the landlady had knocked on their door, along with several of her brothers and a stack of cardboard boxes; she was demoralized, she said, by all the late rent payments and also by certain, um, sounds that came from their apartment with alarming frequency.

“Ha,” Joseph concluded.

Josephine flushed, with both shame and fury, remembering just a few mornings earlier, how she’d been crying — another day of searching for jobs, walking around worthlessly with nothing to do, wandering through the park in search of vistas, everything essentially the same as it had been in the hinterland (hinterland, hint of land, the term they used to dismiss their birthplaces, that endless suburban non-ness) — before he left for work, how he’d insisted on lying down on the bed with her even as she insisted that he leave so as not to be late. This whole summer, blinding Technicolor days interspersed with soggy days that smelled like worms. And during the heat wave earlier in the month, their apartment hot and humid with a heat and humidity unknown in the hinterland, the fridge began to make a painful thwunking sound every eight minutes, and in the dark she had felt like an alien and had desired him, her alien cohort.

At seven the next morning, the storage facility would pick everything up; Joseph had already arranged it. THIS BELONGS TO SOMEONE, he penciled on a scrap of paper. He wrapped the paper around the lampshade.

“We can’t just leave our things out here alone,” she protested.

But he had started off down the street toward the Four-Star Diner. In lighter moments, they’d speculated about why the Four-Star hadn’t gone ahead and given itself the fifth star. She hesitated, then trudged after him. He reached his hand back for her without turning around. The diner was close enough that from the corner booth they could keep an eye on the misshapen lump of their stuff. They ordered two two-eggs-any-style-with-home-fries-and-toast-of-your-choice-plus-infinite-coffee specials.

“I got the job,” Josephine remembered to tell him, her worry about how she’d keep the details of her work secret from him now displaced by the larger worry of their homelessness.

“There you go, kids,” the waitress said. Her hair was a resplendent, unnatural shade of orange, the exact magical color Josephine had wanted her hair to be when she was little. The name tag on the waitress’s royal-purple uniform read HILLARY.

“Perfect,” Joseph said.

“Anything else?” the waitress said.

“She needs a vanilla egg cream.”

Which she did.

The waitress winked and spun off.

“A toast.” He raised his coffee cup. “To bureaucrats with boring office jobs. May we never discuss them at home.”

Getting evicted had made him flippant. But her hands were damp and unsteady, slippery on the ceramic handle.

“Home schmome,” she said.

“Diagnostic Laboratory,” he said. “Agnostic Laboratory.”

He was looking at the diagnostic laboratory across the street. A truck had just parked in front, blocking the “Di.” Their favorite kind of coincidence.

“Good eyes,” she complimented.

Hillary was the type to let them stay the whole night, and they did, drinking infinite coffee and creasing the sugar packets into origami and eating miniature grape jams straight out of the plastic squares, trying to stay awake.

It was Hillary who woke them the next morning, sliding a pair of pancake breakfasts drenched in strawberry goo onto their table. Joseph had pleather patterns from the booth’s bench imprinted in his cheek. As he sat up, he looked to Josephine like a very young child, far too young to be married.

“On the house, kids,” Hillary murmured.

Josephine stared at the large tattoo of a green snake winding up Hillary’s forearm. She couldn’t tell whether the woman was thirty-five or fifty-five.

“I tell fortunes, that’s why,” Hillary said, noticing her noticing the snake. “I’ll tell your fortune anytime there’s not a Saturday-morning breakfast crowd banging down my door, okay, sugarplum?”

Josephine smiled politely. She and Joseph didn’t believe in fortunes.

Only a few of their things (both pillows, a folding chair) had been stolen off the sidewalk in the night. They arranged the small storage unit nicely, a tidy stack of boxes, the bed and bookshelf placed as one might place them in an actual bedroom. He slung a weighty arm over her shoulders and they stood in the doorway, gazing at their stuff. As he heaved the orange door downward, she kept her eyes on the jade plant — hopefully hearty enough to handle this.

It didn’t seem to put the stranger off when they arrived at his door laden with luggage, as though they were ready to move into the sublet right that second, which they were. Within a couple of minutes, he’d explained the history of his name and shown them the entirety of his humid one-room apartment: a snarl of grayish sheets on the futon, whirlpools of old batteries and receipts and junk in every corner, a stately red electric guitar gleaming on a wall hook. A subway train strained past the single soot-colored window on an aboveground section of track, the same line that would moan them toward work on Monday. Throwing dirty socks and boxers into a duffel bag, grabbing the guitar from the wall, the stranger explained that the government was after him because he’d won the lottery, so he had to take a drive and sort some things out.

“If anything happens to those plates, I’ll die.” He pointed at four plates perched precariously upright on the narrow shelf above the mini-stove. Their green vine pattern encircled scenes of English gardens, maidens and gentlemen strolling among roses. Josephine nodded; she was always careful with things.

He left in a rush, gratefully shoving the cash they handed him into the duffel, and there they were, four walls, never mind the state of the toilet.

When she returned from her second Thursday at the new job, he wasn’t at the stranger’s apartment. She pulled a postal notice off the door and stepped inside just as she heard the three-headed dog heave itself against the door at the end of the hall. Her hands felt weak and her eyes hazy. She added the postal notice to the stranger’s feral pile of mail on the bedside table. She sat down on the futon. She called Joseph’s phone. It went straight to voice mail. She didn’t leave a message.

She opened the mini-fridge. There was half an onion and some expired sour cream. She was hungry and not hungry.

She decided to do good things. She lit the candles. She gathered up all the dirty laundry, sheets included, and tried to remember if the stranger had said anything about the location of the building’s laundry room. But then she realized she had no quarters or detergent, and the thought of remedying those problems felt insurmountable. Anyway, they’d made it this far without doing laundry.

She found couscous and chickpeas in the cupboard. She found curry powder. She cut up the onion, turned on the burner, made something, ladled the concoction onto two of the stranger’s green heirloom plates, spread the blanket on the floor, put a pair of candles in the middle, folded paper towels into napkins. She was pleased at her resourcefulness, notwithstanding her failure in regard to the laundry. She knew he would come in the door any second; every move she made, she imagined him walking in on that particular tableau, of her slicing or stirring or serving or folding, and she anticipated the exact expression he’d make, the thing with the eyebrows, the faux surprise, pretending he’d forgotten that she too could cook. The food was cooling on the floor. She called his phone again; voice mail again. She turned on the radio balanced on the ledge in the stranger’s shower stall and pretended the newsman’s voice was Joseph talking to her from the other room, making measured and tranquilizing predictions about the future and the stock market. She waited, then devoured her food. She called him a third time and left a peevish voice mail. She texted him a single question mark.

Time passed; more than an hour. She called him again, told his voice mail that she was kind of freaking out. She vacillated between worry and rage. She couldn’t stand to spend another second inside this apartment without him. There was a rotten smell emerging from the closet. For the first time it occurred to her to wonder if he’d left any sort of note. She shuffled through the stranger’s unruly mail. The postal notice that had been on the door earlier slipped to the floor. She picked it up. She was about to stick it deep into the middle of the pile when the familiar letters caught her eye.

In the intended-recipient box: JOSEPHINE NEWBURY.

But they hadn’t told anyone the address of the sublet.

She examined the notice. FIRST DELIVERY ATTEMPT FAILED: Package could not be delivered/signature needed. There was no information about the sender. Her fingers were quivering. She blew out the candles. She turned on the overhead light. A train ached past the window.

She now detested the automated lady who repeatedly offered her the option of leaving a voice message for Joseph Jones. Who, after many messages left, informed her that Joseph Jones’s voice mailbox was full. She saw that her text had never been delivered. She considered calling the police. She imagined them laughing at her. A husband a few hours late getting home. Sorry, baby, you’re not the first. The overhead light stared her down. She turned it off and sat awake on the bed for many hours.

At her desk on Friday, logging files into the Database, Josephine began to believe she was the only person in the entire building. It was so silent in 9997 — no noise but the sound of her fingers on the keyboard, her fingers opening the files — that she sensed a scream beneath the silence, a shrill shriek she recognized as the flow of her own blood in her ears, yet it sounded like a banshee trapped in the walls. Those pinkish clawed walls — she generally avoided looking at them, but today she got stuck staring at the mysterious smudges and old fingerprints, as though the walls themselves might reveal his whereabouts.

Tonight she would call the police, and the parents, who had warned them what would happen if they left the hinterland. Her mother had stood in the beige kitchen of their hinterland rental, talking about the thing she’d seen on the news: nowadays, gangs of teens in the big cities would just come up to strangers at random on the street and punch them. Just punch them in the face! As part of some gang initiation or something. And that was just the kind of horrid thing that happened in some places and not others. And what if, say, Josephine were to be pregnant at some point, and a gang of teens just punched her on the street? What then? Her mother knew exactly how to kill her every time. Her conversations with her mother were a list of things she thought but didn’t say. Why would you move to a place where you don’t know a living soul? (Haven’t you noticed that our life here is not progressing, Mom? That we’re stuck? That we’re getting flattened by the freeways?) You’ll be all alone there! (What about Joseph, Mom?) Friendless! (I’ll be with Joseph, Mom. Love of my life, Mom.) But by then her mother was crying — melodramatic tears, yet still tears.

Friendless! Friendless! It lingered like a curse.

After work she didn’t know whether to dawdle or rush on her way back to the stranger’s apartment, and she ended up doing something in between, dashing ahead for a while and then hanging back. The three-headed dog was silent as she searched for the correct key. Before she’d inserted the key, the door opened.

Joseph held a large red fruit in his right hand.

“You!” she said, furious and overjoyed.

He pulled her into the room and double-locked the door behind her. Then he handed her the fruit.

“What’s this?” she said.

“A pomegranate.” He sounded tired. But also, maybe, elated. That note of elation or whatever it was — it made her uneasy.

“Where the hell were you?” she said, wishing she were the kind of person who could recognize a pomegranate when she saw it.

“Working,” he said. “It was urgent.”

“You didn’t call.”

“It was urgent,” he repeated. “An emergency.”

“I thought your job was boring.”

“There was a deadline.”

“You should have called.”

He cupped her neck with both hands and smiled at her, a frank smile, his eyes direct into hers. His irises were nearly black.

“You should have called.”

He nodded.

An ice cream truck passed down below, its gleeful tune crackling through a malfunctioning speaker.

“If you ever do that again,” she threatened.

But he was already heading into the kitchenette to fry four eggs in lots of butter.

He flipped the eggs with his typical ease, yet she noted certain things — the swift rhythm his fingers tapped on the spatula, the shakiness of the water glass in his hand.

She didn’t want to speculate. It was hard not to speculate.

“Did you — ” she said.

“Grab me the pepper?” he said.

She passed him the salt, the pepper, the plates.

They sat cross-legged on the floor in the candlelight, their knees touching. He told her about the new sublet he’d found for them — a garden apartment not far from here, on the same subway line, a tad farther from downtown but nicer than this place. And soon their credit would be restored and they could get their own place and start the different kind of life anew.

“Hug me,” she said when they were done eating. She could hear that she sounded whiny, like a small child. But he owed it to her.

Joseph set their plates aside. He hugged her. It was awkward to hug sitting up so they lay down on the blanket on the floor.

There had been moments, last night, when she had imagined him never returning: life without Joseph. Recalling that abandoned, bereft version of herself, she pressed her hip bones against his hip bones. She felt him respond to the pressure of her and it made her proud.

“Hello,” she said.

“Hello,” he said.

She unsnapped her skirt and squirmed out of it. She pointed at his cock, thick and solid inside his pants.

After, it was time to cut the pomegranate.

“I’ll do it,” she insisted, even though she had no idea how to do it.

She pulled down one of the stranger’s heirloom plates, balanced it on the narrow strip of countertop, jabbed at the pomegranate with a steak knife. Thick red blobs of liquid shot out of the fruit, spraying the wall and the cabinets. The plate flipped off the countertop and shattered on the linoleum floor.

Joseph and Josephine stood guiltily on the sidewalk beneath the streetlight in the slight rain, surrounded by overstuffed suitcases and canvas bags brimming with uneasy contents. A mostly drunk bottle of cheap white wine poked out amid stale laundry. Their umbrella was broken, its elbows splayed like a bad joke. It was desolate beneath the train tracks. No cab came along. Then a cab came along, but its driver sped up when he saw them. They waited a very long time. In the building behind them, the three-headed dog stirred, as dark and frenetic as ever, and a fake heirloom plate charaded among the other three.

The cabdriver who finally picked them up told them all about the faraway farm he owned; he raised cows and grew bananas on another continent, and soon he would return to that place to live forever. Josephine felt ill with envy, but still she politely inquired about growing practices for tropical fruits.

Instead of a garden, the garden apartment possessed a dim entryway that smelled like a cellar. There wasn’t even a flowerpot. There was, however, as Joseph pointed out, a butterfly quilt on the bed.

“And the bathtub is pink,” he announced from the bathroom.

She felt bad that he felt bad for not knowing that “garden” was a code word for “basement” in housing ads here.

“I’ll take a bath,” she said, trying to be okay with things.

But when she went to draw water, black gunk bubbled up from the drain. She gagged and ran to him in the kitchen.

“It’s just a baby,” he said.

She was confused for a moment, until she noticed a small cockroach plodding toward the fridge.

“I just want to feel immaculate for a few minutes a day,” she said.

Walking outside in the sun made Josephine feel immaculate. Peppermint ice cream and sleeping for eight hours and not having to touch any gray files and giving dollar bills to subway violinists and drinking big glasses of water and buying a 50% off wall calendar of nature scenes from the hinterland. Joseph did what he could, though the weekend was often overcast. And though he had always been a fidgeter, though his fidgeting had been a decade-long irritant to Josephine, it had escalated to a terrific new level.

“What’s wrong with you?” she finally said on Sunday afternoon as he fiddled simultaneously with the table leg, the saltshaker, and a spoon.

“I’m scared,” he confessed.

Sympathy flooded her. She seized the saltshaker and the spoon. She knew with sudden, cool certainty that he would never again abandon her; that she would never again sit through a night alone wondering where he was. At least not until he died.

“Join the club,” she said.

“Loin the lub,” he replied.

On Monday night, she passed a take-out Chinese restaurant on her walk from the subway back to the so-called garden apartment. She stopped to look through the big window at the illuminated menu, contemplated the oddly appealing possibility of oversweet sesame chicken, felt somewhat hopeful.

But then she noticed a man in jeans and a gray sweatshirt standing inside the restaurant — his skin ill against the pale green walls — staring hard at her. There was an eerie focus in his eyes, as if he’d singled her out. Or he could have just been gazing vacantly out the window.

Unnerved, Josephine hurried onward. As soon as she began to walk away, the man in the gray sweatshirt headed briskly toward the door of the restaurant. She sped up, running the final blocks, unwilling to look back to confirm that he was following her, worried that a backward glance might provoke him. Only once she had reached the dubious safety of the dark stairwell did she dare a glance. The sidewalk behind her was empty.

She smiled a thin, scornful smile at her nervous little self. Still, it was a relief to stumble down the cellar steps, to throw her bag on the rickety chair and call out for Joseph.

He wasn’t there. She almost enjoyed her slight buzz of impatience, of doubt; when he arrived, any moment now, she wouldn’t take him for granted.

His phone went straight to voice mail. His voice mailbox was full. She had just hung up when a text message dinged. She seized her phone, but the text was from her mother: Apples in season went to orchard today you should be here. Pie!

She sat at the kitchen table. The basement was all shadows and earth smells. At least there were no cockroaches in sight. She crept through the rooms. Even the most innocuous objects had taken on an undeniable malevolence — the rag rug, the plastic trash can, the butterfly quilt. She returned to the kitchen. She drank a glass of water. She felt unwell. She was just transitioning into fury when her phone began to buzz on the table.

“Where are you?” she demanded.

The brief reply was a blur of indecipherable noise.

“Where are you?” she screamed.

This time the response was a mangled mutter. Maybe a trio of gerunds (doing gluing screwing) or maybe not. Distorted syllables, and then, clear as anything, an exhausted sigh before his voice sank back into the muck of static.

“I can’t hear you!” She could hear how savage she sounded.

He launched into a bunch of words but she only caught fragments, blips and fuzz.

“… sticksorhoe… portentgif… nessandheal… ed… oon…”

“What?” she shrieked.

He said something that seemed to end with an exclamation.

“What?”

“… so that — ” Joseph’s voice emerged loud and perfectly distinct for two words, followed by the total silence of a lost connection.

The Four-Star Diner was packed with its Monday-night dinner crowd, but even so Hillary hustled over the second Josephine stepped through the doorway. Her orange ponytail was brighter than anything else in that bright place.

“There you are!” Hillary bellowed. “Right this way, sugarplum.” She put an arm around Josephine and bustled her toward the row of red stools by the counter. She looked older than Josephine remembered. “What’ll it be? Tuna melt? Grilled cheese? Wait, no, breakfast for dinner — how about waffles? Pancakes? Strawberries, right? Bingo! Lady in need of strawberry pancakes! Listen, I’ll be right back, I’ve got a table of grannies that wants a million things.”

Hillary delivered the food quickly, with a wink, and Josephine ate quickly, almost rudely, the way Joseph always ate. The instant the pancakes were gone, she once again had that feeling of not knowing what to do with herself; the long fast walk to the diner had been something to do, eating had been something to do, but now the grief was beating the frenzy, the fury. Hillary came by to wipe down the counter.

“So, tell me,” she said to Josephine as if they were best friends. “Where’d he go?”

Josephine focused on the saltshaker.

“Oh honey,” Hillary said. “You look just terrible! I knew it the second you walked in the door. Actually, I knew it the second you kids spent the night here back whenever it was. I told you I’m a psychic, right? Hang around till things quiet down, okay?”

Josephine rested her forehead against her fingertips, felt the Braille of her rising zits. She drank a few of the mini-creams, flinging them down her throat like shots. The dinner crowd thinned. She watched a large family group clogging the exit, the merry chaos as they located the grandfather’s coat, the baby’s pacifier. Idly, distantly, she wondered if she’d ever typed any of their names into the Database.

She was still entranced by the baby, who had violent hiccups and messy curls, when someone gripped her hand and flipped it upward on the paper place mat. Josephine twisted around to find Hillary leaning over the counter, already deep in the study of her palm. The smell of cigarettes and Dove soap and syrup. The sleeves of her royal-purple uniform were rolled up, showing off the green snake on her forearm. Her hand was warm, almost hot, and muscular, and enviably dry; Josephine’s palms were always clammy. Though it was awkward, her fingers pinned down this way by a near-stranger, she couldn’t deny that Hillary’s touch felt as good as someone brushing your hair, someone massaging your shoulders.

“You have a lot of unused capacity that you haven’t turned to your advantage,” Hillary murmured, squinting at the lines. “Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside.”

Josephine tried to pull her hand away, but Hillary wouldn’t let go.

“You’re critical of yourself,” she persisted. “At times you have serious doubts about whether you’ve made the right decision or done the right thing.”

Josephine put her free hand up to her neck, attempted to locate the knot in her throat.

“You’ve found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others,” Hillary said slowly. “You pride yourself on being an independent thinker. You’re often introverted, wary, and reserved. Still, you frequently desire the company of others. Security is one of your major goals in life, but you become dissatisfied when hemmed in. Some of your aspirations are unrealistic.”

Hillary stopped, noticing the effect of her words, and pulled a napkin from the metal dispenser, placed it in Josephine’s exposed palm.

“Don’t worry,” she said, “it’s normal to cry. Everyone does.”

Josephine felt naked, ashamed, far too understood. She swiped the napkin across her face and stared at the unfair red hair. Was Hillary kind or cruel?

“I’m just the messenger, sugarplum,” Hillary said. “Are you ready for the good news?”

Josephine spread her hand out on the countertop again, but Hillary ignored it.

“Though you have some personality weaknesses, you’re generally able to compensate for them,” she announced.

Josephine waited. Hillary smiled.

“That’s all?” Josephine said.

“That’s plenty,” Hillary said.

“Where is he? When will he come back? Will we stay married? Will we have kids? How many? How long will I live?”

“Oh sugarplum,” Hillary chided. “You don’t want to know any of that.”

“Yes I do!” Josephine was alarmed by the screech in her own voice.

“Want a refill on that coffee?” Hillary said, standing up straight again and offering Josephine the dazzling, indifferent smile of any great diner waitress. She glided away as though nothing significant had passed between them.

Josephine left a huge tip, wound her scarf around her neck as many times as possible, and stepped from the pink and yellow glow of the diner out into the night, dead leaves racing down the concrete all around her.

“Don’t worry so much, sugarplum!” She thought she’d escaped unnoticed, but Hillary tossed out the penny-bright words before the door blew shut. “It’s bad for your skin!”

After work on Tuesday, she stood in the doorway of the sublet and said his name seven times before accepting that he wasn’t there.

She closed the door behind her. Stood perfectly still in the entryway. She had no idea at all what to do with the next minutes of her life. It was best and easiest to stop here, not move another inch. Not think about who to call or what to report. She would have stood there forever, just blinking and breathing, except that soon she became desperate to pee.

She ran down the unlit hall to the bathroom, swearing to herself that as soon as she was done she’d come right back to the entryway, stand there still. She peed in the dark, wiped in the dark, flushed in the dark. On her way back to her post, she spotted something in the bedroom: a long black shape on the bed.

She thought it was an intruder before she thought it could be him.

Naked, and sleeping on his side, as he always did.

Her life had become so odd.

She shrugged off her cardigan, stepped out of her shoes. She lay down on the butterfly quilt behind him and cupped his body with hers, as she always did. A few minutes of stillness.

Sometime soon, sometime very soon, she would let go of him, would wake him up to demand explanations, pretending she’d never held him at all.

When she lifted her arm off him in preparation for the fight, he grabbed her wrist. She gasped, startled — he had seemed so dead asleep.

“Don’t go,” he said, pivoting around to grab her other wrist.

“Ha,” she said coldly.

He sat up, her wrists still locked in his fingers. His skin looked strange, evil, gleaming nude in the pale alley light that snuck down the window well.

She was having trouble recognizing him. He seemed euphoric, rich with energy, almost superhuman.

“Are you a demon?” she said.

“Demon demeanor,” he said. “Demoner.”

He dropped her wrists and went for the buttons on her blouse. She slapped his hands hard, as hard as she could; it felt good.

“Demeanor?” she spat.

“Nice,” he said, reaching once more for her buttons. “More, please.”

She obliged with another slap.

“Take your clothes off,” he commanded like a rapist. “It’s important.”

“You sound like a rapist,” she said.

He laughed like a rapist. “You were the one who wanted it last time.”

“I wouldn’t have sex with you now for — ” She failed.

“For what?” He was abuzz, brimming over, unable to cap his vitality.

“A million dollars!” she raged, clichéd. “All the tea in China!”

“But you have to,” he said, jubilant. His hands firm again on her wrists. He was naked and she was dressed but they both knew who was really naked and who was really dressed.

She couldn’t understand anything anymore. What was happening to him? Was their life together almost over? Some of your aspirations are unrealistic. He was touching her hand. Maniacally stroking the lines of her palm. It reminded her of something. She pulled her hand away. She curled herself around herself.

“Everything is good,” he said.

She wished to make herself into a perfect sphere, no handles for him to grip.

“If you understood you’d understand,” he said. “Take off your clothes.”

She made a sound of protest.

“Think of it as make-up sex,” he suggested.

“What about the fight?” she said to her knees.

“I’m sorry,” he said, “and I’m not sorry.”

He grabbed her, the ball of her, and peeled her arms from her legs.

She was fierce; she clung to herself; he laughed as though it was a game; maybe it was a game; she swatted at him, she twisted her spine, she pretended to be air but always he got hold of a limb.

She gave up. Lay flat on her back on the butterfly quilt. He trailed his lips down her chin, down her neck, all the way down. That infuriating mix of wrath and desire.

Later, she was above him, eyes shut, pressing her hands against the dust-thickened window, taking those long deep insane lightheaded breaths that come just before, and then, as it hit, she opened her eyes with a scream of joy — there on the other side of the dim window was a man, a trespasser, his splayed fingers an echo of her splayed fingers, his oily face lengthened in an expression of ecstasy, his eyes brilliant gray and wide open. Her scream of joy veered into a scream of horror; her eyes snapped shut for safety.

Joseph rose up from beneath her, puzzled, normal, saying the right comforting things, asking the right concerned questions.

When she opened her eyes again, the window was empty, the maniac vanished. She pulled Joseph back down so they were both low on the bed, hidden. Mistaking her urgency for desire, he pushed himself into her again, and who was she to deny the heft of it, the absoluteness of his presence, the seam ripping beneath them.