interviews

The Bard of Black American Loneliness

Poet Morgan Parker talks about Beyoncé, pop culture & getting out from under the white supremacist patriarchy

To read the poetry of Morgan Parker is to meet a voice brash with intelligent humor and sadness, both youthful and wise, analytical and lush. It’s a voice that assembles a worldview equal parts museum art and pop culture. It likes its wine but is weary of social injustice, and it finds a swagger in observing the everyday tragic.

Parker’s debut Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up At Night was selected by Eileen Myles for the Gatewood Prize in 2013. Her new collection, There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé (Tin House Books, 2017), is a high-concept meditation on the tensions between individual agency and systematic inequality, the weight of history and the ever-visibility of the Digital Age, beauty and black America and performance. Recently, Parker took a break from “slowly answering a billion emails and coming up with bad tattoo ideas” to discuss space on the page, why she doesn’t have time for gimmicks, and carving life cycles into a collection.

O’Neill: There’s a line in “The President’s Wife” that goes, “Is lonely cultural.” I think many of the poems in the collection gesture toward that question. Could you talk about that? Also I’m wondering if there is any truth in the inverse, that countercultures offer a model of radical sociality. Is it more complicated than that?

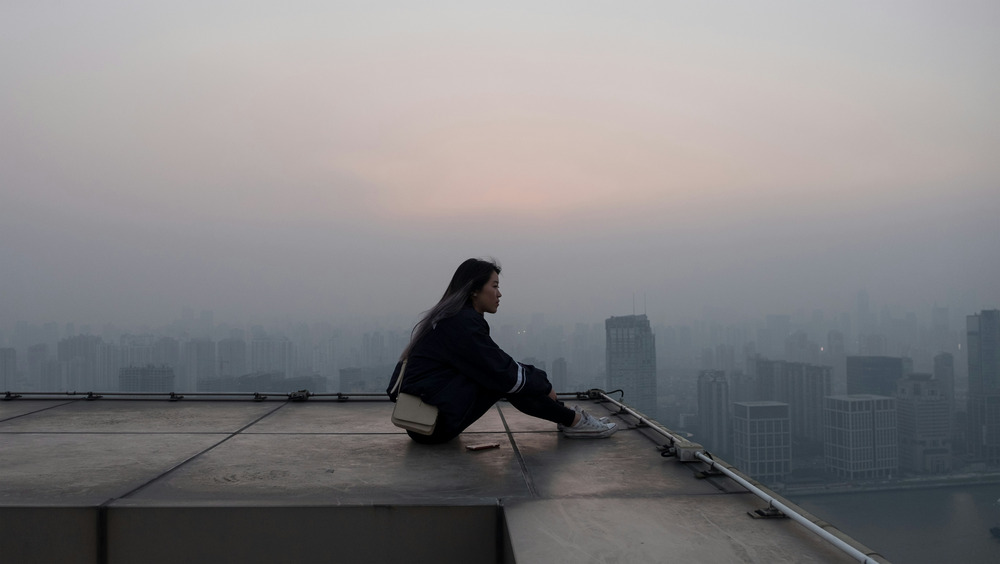

Parker: Dang, ok. So, I think it’s probably both, like, we need countercultures to help us feel like we belong to something, and I guess I’m talking specifically about POC or marginalized folk because black American loneliness feels like a particular type or at least, for myself, I’ve been trying to understand the connections between the history of black women in America, the weight of it, and my own neuroses, deep sadnesses. My number one thing in therapy is loneliness, followed closely by America, so I guess a lot of the book is trying to get at that connection.

America has systematically placed loneliness on us, like, we’ve been separated from our families, pitted against each other, etc. We’ve been divorced from a sense of belonging or home. Weird example but you know how in High Fidelity dude is like, was I sad because I listened to pop music or did I listen to pop music because I was sad?

O’Neill: Yes.

Parker: My thesis question is something like that, what came first, what belongs to me versus what I’ve internalized and was placed on me

O’Neill: That comes through really beautifully throughout, but I’m struck by a poem toward the end. “The Book of Revelation” ends, “She says peace is something/ people tell themselves.” There’s a restlessness to the speaker(s) of this collection, and I’m wondering if we’re meant to read this lyric ‘I’ as one speaker, first off, and second, if so, is peace what the telling of these poems constitutes or gestures towards?

Parker: Well, peace is the goal. The speaker(s) are ISO peace, but also skeptical that it even exists. That question of if the speaker is one or many… I think the answer is both? Obvi I wrote all the poems but each speaker’s in a different state of mind/challenging specific and different sources, and I guess part of the project of the book was trying on all of those voices and inhabiting all of them as truth because people are complex! I feel like I’m minimum 17 people throughout the course of one day. Lol is my book leaves of grass?

O’Neill: Yeah, I’d peg you as a cooler Walt. Also, I love the moments where the speaker(s) reflects on her self. Many times reading the collection I was struck by moments of swaggering melancholy or maybe melancholic swagger in your lines, which was really seductive to me. The speaker(s) carries sadness, certainly, but there is also this big, magnetic personality that seems a little bit aware that she kills.

Parker: Yup. It’s like the tragic heroine, I guess, how miserable it can be to hold greatness and to have your greatness continually obscured and doubted.

O’Neill: The speaker(s) of your poems returns repeatedly to the sense that she is not sufficiently woman.

Parker: There’s a thread in the book that wants to ask what femininity is and again, who gets to define it, standards of beauty, etc. I mean, the impetus for some of the first poems in the book was just looking at Beyoncé, so of course there’s this meditation on beauty, on what’s expected and accepted, which also has to do with traditional ideas of femininity, desirability. Man, they ask so much of us.

“There’s this meditation on beauty, on what’s expected and accepted, which also has to do with traditional ideas of femininity, desirability. Man, they ask so much of us.”

O’Neill: Truth. In a weird way, I think this comes out most in “Beyoncé Prepares a Will.” There’s a sense that even when she’s dead — which, first off, the unimaginability of it to some people is pretty indicative of how she’s become a symbol beyond human — she’s going to have this image to uphold. I shouldn’t say that’s where it emerges the most. But it is evoked.

Parker: For sure! And it goes the other way too, like before, during, and after life, she doesn’t have ownership over her own body or narrative. I guess that’s one thing Beyoncé and I have in common.

O’Neill: Oh I think you guys have more in common. You’re both very strong and stylish and moving. You have a much stronger voice, though. The Bey Hive is going to come after me. Whatever. I love Beyoncé. Onward.

Parker: Lol my thoughts exactly.

Magical Negro #607: Gladys Knight on the 200th Episode of The Jeffersons

O’Neill: Going back to that question of control over the narrative, I also think about the way you use money as a trope in the collection. In Hottentot Venus, you write, “No one worries about me/ because I am getting paid.” In “Welcome to the Jungle,” you write, “art is nice but the question is how are you/ making money are you for sale.” There seems to be a logic there: you are still paying even when you earn. If that makes any sense. And I’m not just talking about in the marketplace.

Parker: Yup.

O’Neill: Although when aren’t we?

Parker: For sure! You’re buying and being bought at the exact same time, and money is supposed to be this kind of salve or apology, but it’s empty.

O’Neill: Speaking of empty, you beautifully spatialize silence in “The President Has Never Said the Word Black,” so that what is not said becomes a physical gap on the page; you really make us attend to elision, using the page to make visible what’s become naturalized or uninterrogated. Can you talk about how you use spatial techniques in other poems like “Lush Life,” “13 Ways of Looking at a Black Girl,” “The Book of Negroes,” “Rebirth of Slick,” and “Beyoncé On The Line For Gaga”? Shit. That’s a lot. Maybe you could just discuss more generally.

Parker: This is the best thing about poems. They get to be visual and flexible in a way prose can’t. The way I use space in “The President Has Never Said The Word Black” is different than how I usually do, but in general, poetry is about reading between the lines, reading what isn’t there as much as what is.

O’Neill: You used to work in the world of visual art and flag “We Don’t Know When We Were Opened (Or, The Origin of the Universe)” as after Mickalene Thomas, the painter. Obviously, I already brought up “Hottentot Venus,” which is also an allusion to visual art. How do you see your work in conversation with other artistic media?

Parker: It’s also visual.

O’Neill: Oh wait sorry did I go too fast? Eager fucking beaver over here.

Parker: No! Was just about to say it’s visual. We on the same page, like, “13 Ways of Looking at a Black Girl” feels almost like a piece of visual art more than a poem. If I were a painter I would make it a painting somehow. But I ain’t, lol. The visual arts are super important to me, huge inspiration for so many of the poems. I also wanted the book to be visual, if that makes sense: the imagery, the setting, the clothes, the hair, the vision. And it was important for the book to be in conversation with not only literature but music, visual artists, etc.

O’Neill: You mention jazz.

Parker: I loooove jazz because I am a grandpa.

O’Neill: And yet, you also thread throughout the collection a very contemporary and complicated relationship between humans and machines. There’s discussion of white emoticons. In another poem, the speaker describes herself as a screen. Then, in “Beyoncé, Touring in Asia, Breaks Down in a White Tee,” there’s that line: “honey we need the machines to live.” Can you talk a little bit about that?

Parker: Yeah, I never really think about that, but it’s true — I think it’s because I’m meditating so much on how we’re perceived, what our bodies are, how we see ourselves, and that’s very wrapped up in technology in 2016. 2017? Whatever, rn. Technology teaches us about ourselves and also distances us from ourselves. It’s how we communicate and it also replaces language. That sounds kind of basic, but it felt important to touch on, in terms of authenticity, performance, presentation

O’Neill: I don’t think it’s basic. “It’s how we communicate and it also replaces language” is a way I wouldn’t have thought to think of it. I have a couple of more general questions, but first I want to ask: what do people miss in your work or misinterpret?

Parker: Hmmm. I worry about the work being labeled superficial, because of its use of pop. I worry about it being labeled unserious, because I like telling jokes. Of course, assuming that it’s anti-Beyoncé, or even particularly pro-Beyoncé, is false

O’Neill: I see it as very serious and in dialogue with a lot of the excellent writing that deals with the semiotics of pop culture.

Parker: I agree that pop culture is incredibly pertinent and scholarly. I do think it’s easy — especially because I’m a young black women — for people to write my poems off as fluff, or opportunistic, or gimmicky. Frankly I do not have time for gimmicks. I’m like trying to get out from under the white supremacist patriarchy.

“Frankly I do not have time for gimmicks. I’m like trying to get out from under the white supremacist patriarchy.”

O’Neill: It also seems like those critiques are premised on some very incorrect notions of what poetry is and what poetry should do.

Parker: Yuuuup. Man I am sick of talking about that.

O’Neill: Could you discuss the work of arranging poems into a collection? What were you thinking about in structuring the book?

Parker: I love ordering books. This went through very many rounds. There were so many journeys the speaker could take, and so many different poems I could use to anchor the book. In the end, I decided to loosely structure the book around life cycles.

The life cycle of Beyoncé — “Poem on Bey’s birthday” and “Beyoncé Prepares a Will” as bookends.

There’s another cycle that’s loosely about depression or loss, or maybe, the battle with the self/ the self’s history, so… “Hottentot” being up front as a kind of background/ source for the speaker of the book, and “Funeral for the Black Dog” is literally a kind of funeral for my own depression. So the book goes through a metamorphosis of self-loathing, investigating the source of that self-loathing (which includes owning but also seeing that the self isn’t the only culprit), and then resolving to regain agency.

I should be clear that I don’t expect readers to pick up on all of that, but there’s a ghost of that general trajectory in the ordering of the poems.

O’Neill: You’re an editor at Little A, as well as a poet. All writers edit their own work, of course, but I’m wondering the extent to which your editor self and writer self — if you even think of these as separate parts — interact in your writing practice.

Parker: I definitely self-edit as I’m writing, but not to the extent that everything I write is gold. I allow myself to write a lot of bad poems. That’s the writer me. The editor me comes in around draft three, or after a significant amount of time. I also learn a lot of editing techniques from working with other writers. There’s so much more room to bend and play and be flexible when the work isn’t your own, so I do try to take that kind of fresh approach to my own work when I can.