Novel Gazing

The Book That Fueled My Eating Disorder

Joan Jacobs Brumberg’s “Fasting Girls” let me intellectualize what I was doing to my body

Novel Gazing is Electric Literature’s personal essay series about the way reading shapes our lives. This time, we asked: What’s a book you misunderstood?

One day when I was in high school, I started a diet. I don’t remember why, only that I went home after school and was so hungry that I laid in bed and cried. I was too hungry to read, to do homework, to watch TV; I tried to fall asleep. Over months I became accustomed to a level of hunger that until that point had been unimaginable to me. I still ate, because my family would have noticed if I stopped altogether, but not much: a small bowl of dry Cheerios in the morning, a no-fat Yoplait whipped yogurt at lunch, the smallest portion I could manage of whatever my mother had made for dinner. I thought that about 500 calories a day was appropriate. My period stopped, I noticed a layer of fuzzy blonde hair emerging on my back, and everyone commented on how slight I was. I was already thin, so probably people thought I was just a little more thin than I had been. A growth spurt, being a teenager.

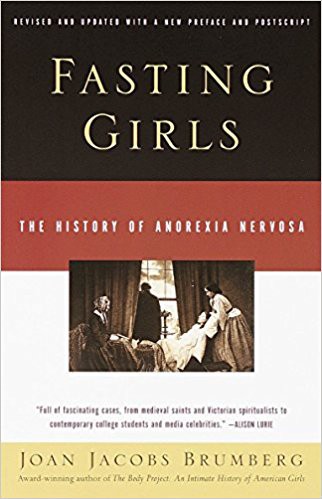

Fifteen years out, the strangest thing to me about this time was how extensively I researched what I was doing to myself. I remember going to the library weekly, memorizing the aisle where I could find books on anorexia and other eating disorders, reading about women who one day had simply stopped eating. Even as I was eating so little that I would be caught by dizzy spells every time I stood, I was fascinated and repulsed by women who had taken things so far that they were sent to the hospital or even died. Joan Jacobs Brumberg’s Fasting Girls: The History of Anorexia Nervosa was a particular obsession, a book I checked out repeatedly.

It’s well known that girls with anorexia tend to research their own eating disorder, and misuse the available resources. For every website listing the signs of an eating disorder, there is at least one girl with an eating disorder reviewing that list to be sure she doesn’t reveal any of them, but also to assess her own qualifications. In my obsessive, cruel dieting, I considered stories of anorexia as some sort of a guide: do what these women did so successfully, only a little less. This was still early days of the internet, and I logged on a few times to read through forums of women discussing and supporting one another in their anorexia — forums I learned about through one of my library books, though I don’t remember which one. If the world around these women was telling them they were sick, they could come to this website and reaffirm their commitment to a near-total abstinence from food. Probably luckily for me, something about these discussions horrified me, and I retreated to the library’s selection of five or ten books on the subjects.

It’s well known that girls with anorexia tend to research their own eating disorder, and misuse the available resources.

What made Fasting Girls such an intriguing book for me was how it placed anorexia, and my own diet and confused feelings about my body, within a history of disordered eating. It turned out that anorexia wasn’t a new thing but went back centuries, to medieval women whose ability to survive without food was a miracle. It was a history, but it was also a guide and an encouragement: here is how this woman did it, and this, and this. As someone who writes about anorexia, Jacobs Brumberg likely knows that some of the readers of her history are finding it not because they are curious about the topic but because they are obsessed by it, because they need to understand their own inability to ingest food. While I read the entire book, it was the modern section that obsessed me, her placing this disease into the more recognizable world of asylums and psychiatry and forced feeding. Jacobs Brumberg’s writing could be dry, and I wonder if this wasn’t part of the appeal: unlike the forums that would have provided more “useful” guidance, her work was scholarly, something I could explain away — to others and to myself — as a matter of historical rather than personal interest.

That fall, I worked in a Christmas shop in my small town, selling expensive glass ornaments and creepy old-fashioned dolls, made of newsprint under their dresses and selling for a hundred dollars apiece. My most distinct memory of the job is my habit of walking into ornaments, clueless and confused. Every week, there was another shattered $50 ornament that I had to write down in a spiral-bound notebook next to the register. One day, walking around the owner’s house after putting our store’s sign out on the street, I walked straight into a clear decorative glass orb she hung from the porch, breaking it and leaving myself with a bruise and a throbbing headache. The crash was so loud that the whole family came running out to see what had happened. These have for years been some of my best work stories, examples of my endless clumsiness, but all those ornaments would have probably been safe if I just let myself eat a decent meal. When you aren’t eating, life becomes one endless battle against dizziness and hunger, but I remained devoted to the idea that I could be one of these overachieving girls with such impressive willpower I could literally starve myself into nothing, into a person who would vanish when you turned her sideways. I would go home from work and pull my library books from under the bed, find in them an encouragement to not give up.

I had forgotten about Fasting Girls until a few months ago, when I read Emma Donoghue’s The Wonder for my book club. The Wonder is about a nurse who’s been assigned to watch a young girl who is apparently surviving on air — a miracle. Donoghue must have read some of the same books I had obsessed over as a teenager, in researching her story. The Wonder is in part about the tradition of the original “fasting girls,” the namesakes for Jacobs Brumberg’s work. Once the nurse figures out that the girl is in fact starving herself, that she is a troubled child rather than a miracle, the novel becomes a question of how you can fix a physical problem that is actually a mental one. How do you talk someone into eating, when she’s become convinced that the only way to fix her world is to not eat?

Although it’s not an abnormal behavior for someone with anorexia or disordered dieting, it seems strange to me now how carefully and incorrectly I read Fasting Girls. I wasn’t interested in diet books or pro-anorexia forums, but a book that enabled me to intellectualize the harm I was doing to my body had an appeal. The idea of the fasting girls brought with it some idea of reaching another plane of thought and faith, and maybe that’s what I thought I could find — not realizing that by trying to erase my body, my flesh, it would become literally the only thing I could think about. I became more earthbound the more I tried not to eat.

I wasn’t interested in diet books or pro-anorexia forums, but a book that enabled me to intellectualize the harm I was doing to my body had an appeal.

In the end, it was probably my peculiar obsession with Jacobs Brumberg’s work that saved me from crossing the border that separates excessive dieting from the disordered eating that sends you to a hospital and then rehab. Newspaper and magazine stories often unintentionally dramatize their anorexic subjects in a way that is endlessly appealing to a teenager like the one I was. Tell me how much she weighs, how large her arms are, what size pants she wears, and I’ll take those as goals. Tell me how many calories she ate every day, how often she weighed herself, and I’ll do the same. But I could only find these articles by chance — not everything was posted and searchable online at the time — while I could always return to the library, to my same few books. And although I misused her book, I don’t remember Jacobs Brumberg adding any appeal to the idea of anorexia. Parts of Fasting Girls were boring, and I returned to it more for comfort and a sense of my own location than for anything else. I remember her history being a sad one, of offering me a sense of what a waste my actions might make me.

I must have agonized over the decision, but now all I remember is waking up one day and deciding I needed to change. I would eat a regular meal with my family — the whole meal, not picking around the edges. It had been months since I’d had my period and suddenly, something about that frightened me. I realized I had gone too far. Over months I began to eat again, and to avoid the library aisle where I’d spent so much of my time over the previous months. My period returned. Over the following years I sometimes took my incorrect eating in the other direction, staying up late at night to eat muffins surreptitiously purchased from Wawa, entire cartons of Tastykake donuts; then trying, again, to limit myself. I was probably in my late twenties before I felt tentatively secure in my sense of my own body and how I should treat it.

Writing this, I thought I should find a copy of Fasting Girls. I should flip back through it, and remind myself of why I returned to it so many times as a teenager. But my library doesn’t have a copy — one of the largest library systems in the country, probably, and not a single copy. I felt such palpable relief at seeing that blank page. Even fifteen years later, knowing how badly I misunderstood and misused Jacobs Brumberg’s writing, I don’t trust myself to approach it again. I worry that I might fall back in, that whatever part of me aspired to be a worthy subject of her research is still in there, ready to make my body a manageable thing.