Books & Culture

The Broadcaster & The Writer in America

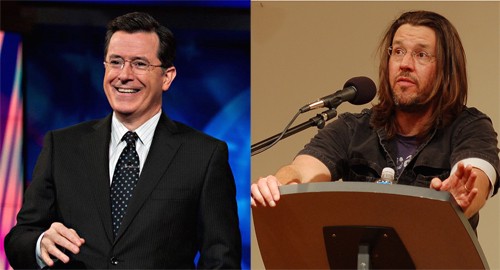

Stephen Colbert returned to the airwaves on September 8th. Stephen Colbert is a broadcaster. David Letterman was a broadcaster. There are great journalists who have also learned what it means to be a broadcaster and be a host. (Think about Jorge Ramos interviewing Carlos Salinas de Gortari or Edward R. Murrow’s dispatches from London, let alone Hemingway’s or Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s respective careers in journalism. (Hemingway’s take on Mussolini remains a favorite.))

But Colbert and Letterman aren’t “writers,” per se, and it’s slightly surreal that this ends up being the obvious point that needs to be reemphasized. (When Salman Rushdie was recently describing how he ended up getting to the point of writing a song for U2 to Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Fallon said, “That’s so deep, man.” Thanks, Jimmy.)

But in lieu of the (perhaps particularly American? (Despite publishing statistics?) Partially Italian? A little bit Brazilian?) anxiety that looks at the world and comes to the conclusion that — as Lee Siegel did — the news has overtaken literature (which I’ve written about previously) or that Joyce would be working at Google were he alive today (let alone the now years-old, multi-tentacled fretting that’s marked Tim Parks’s writing about writing (though my inner editor is tempted to dismiss this as being my version of something like this), it’s worth considering two things — what it means to be a “broadcaster,” and what writers have done in considering what it means to be a broadcaster, and how — in articulating what it means to be a broadcaster today (think of this twinned with this) — we can appreciate what it means to be a writer today (and vice versa.)

In “Host,” David Foster Wallace described a man whose eyes off-air “are usually flat and unhappy” and “alight … with passionate conviction” once they return to broadcast, and how — once on air — we’re dealing with an emotional landscape that trades in “anger, outrage, indignation, fear, despair, disgust, contempt, and a certain kind of apocalyptic glee” created by a man who “has one on-air job, and that is to be stimulating.”

In “E Unibus Pluram,” he writes about how “the result is that a majority of fiction writers, born watchers, tend to dislike being objects of people’s attention”; that — “if we want to know what American normality is, we can watch television”; and that — unfortunately — “we receive unconscious reinforcement of the deep thesis that the most significant quality of truly alive persons is watchableness, and that genuine human worth is not just identical with but rooted in the phenomenon of watching.”

In “My Appearance,” David Letterman is invoked as a force of nature, whereas — per the narrator in the story — “The man has freckles. He used to be a local weatherman. He’s witty. So am I.”

Now what do those three pieces tell us? (That we should read more Barthelme, for one? Or take a tour through David Carr’s archives? (And why did he have to go?)) And what has changed since DFW articulated some of what he articulated? Well — for one — Tahrir Square arrived like the imagistic inverse of a monk burning outside the Pentagon during the Vietnam War and spread hope with quick, quick dispatch across the globe. American satire moved to punch a hole in the political class and the political class tried to re-appropriate satire’s voice (which means that the next logical step is probably something like this.) Roxane Gay arrived. Ta-Nehisi Coates arrived. Twitter went from being a curiosity to a way to be a little bit faster than traditional news wires to a way to organize protests and demonstrations (Occupy Wall Street, Gezi, Hong Kong, Black Lives Matter, Bring Back Our Girls, Je Suis Charlie, et al.) to a way for others to become famous in those contexts to a way to relentlessly harass women for years to a way to humiliate lives because of a single bad joke to ways to transmit and care for refugees fleeing across multiple countries, fleeing fast and far from Bashar al-Assad, Daesch, and others burning a whole country to the ground. (Small wonder that the NSA sees the potential of such power in aspiring to have a handle on such an excess of digital information.)

The capacity and breadth of broadcasting has expanded, but broadcasting itself — as an idea — still feels remarkably capable of being shrunk to size and dismissed. Everyone may talk about Mr. Robot, The Wire, Downton Abbey or whatever with cyclic regularity, but the fact remains that the United States publishes a lot of new books every year — I’ve seen numbers that put it anywhere between 300,000 and a million. And now that cord cutters are the dominant norm, I’d argue that there’s a window of opportunity for people to define television to themselves in a way that you wouldn’t expect — beyond the kind of articulations made at the MacTaggart Lectures — given that television’s continual presence is so good at keeping someone on the judgmental back foot. (Look at this interview between Jon Stewart and Craig Ferguson in 2005, for instance. They could have been saying the same thing today, but the process of ‘feeding the beast’ keeps our understanding of being a broadcaster fluid.)

And writers are still writing, one going so far as to spend a month ensconced at The Seattle Public Library. “Within the first hour,” Gabriella Denise Frank wrote over at The Rumpus, “I realized that I would have to push myself in order to work under the eyes of the same strangers I hoped to inspire. I would have to endure people reading my unformed thoughts before I deleted and rewrote them again, sensing the cast of their unspoken scrutiny.”

And the fact that this balance between our expectation of writers and broadcasters fluctuates so — think of the historical dimension, too, where audiences grew silent because of the expectations partly put upon them by Haydn, Rossini, Beethoven, and others — means that this is not necessarily a particularly intransigent problem. It’s not even an intransigent problem now, globally, as — if you want to look past the experiential level in Paris — you can look at this paper from Gisèle Sapiro, which argues fairly well against the notion of the ‘death’ of French literature as seen from an American perspective. (French literature is alive and well and out there. We’re just not translating it well enough. Or even look to Héctor Hoyos’s Beyond Bolaño to get a sense of how the ‘global Latin American Novel’ is moving in a global context.)

But I think that all this talk partly comes down to the way in which we define our space to ourselves in this country — from notions of rewilding to urban studies to the developmental impacts of technology on children, Michel De Certeau, and beyond. When I first flew up from London to Glasgow in February of this year, I couldn’t get over the fact that it only took about an hour. It’s the length of a flight from Boston to New York, or — if the pilot’s pushing it a little bit — DC. And I was going over an entire country, filled with cities I already knew a fair amount about. And yet — for all the ways in which we choose how to engage in our space — think of post-sex selfies, midnight shift photos sent Instagram’s way, radios left on at the beach, the hovering question as to whether or not Arcade Fire or St. Vincent sufficiently described a certain shade of technological anxiety the way Neil Portman described ‘Amusing Ourselves To Death’ — Montana still remains Montana. You can drive through New Hampshire in pursuit of Presidential candidates and still be stunned at the landscape you see. You can log off the internet for a day, come back on at the end of it, and be absolutely bewildered at the turn everything seems to have taken.

All this activity may leave writers feeling like their work lacks sufficient dexterity, or that they somehow aren’t adapting well enough to the technology of the moment, that they have to pull off big circus-sized ‘tricks,’ or that — like Wallace — the natural appreciation of a certain lack of attention puts them at a storytelling disadvantage of sorts — a disadvantage that people like Colbert and others can capitalize upon — but it shouldn’t. Just because what you write in a notebook isn’t the literal size of the space around you — be it the Grand Canyon, the Mississippi River, the streets of San Francisco or the tattooed greenery of the Pacific Northwest — just because writing isn’t an actual car stereo blaring down a highway, a Mardi Gras parade filling the French Quarter, or the Chicago River turning green as can be come St. Patrick’s Day doesn’t mean that what you write isn’t capable of filling that space, of meeting that space in its own particular method, its own particular way, and its own particular time.